Abstract

Purpose

The incidence of posttraumatic growth (PTG) has mostly been researched after typical traumatic events such as war, violence, bereavement, vehicle accidents, and so forth. This research has shown that PTG also occurs after cancer. This article presents the results of research which focused on PTG and what was related to its incidence, such as the specific reaction to trauma, among patients with hematological cancer (N = 72). The differences in the levels of PTG were analyzed from the perspective of demographic characteristics, characteristics of the disease, and treatment.

Methods

PTG was measured using the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory-Czech version (PTGI-CZ). The associated variables were measured using instruments in measuring benefit findings [Benefit Finding Scale for Children-Czech version (BFSC-CZ)], distress tolerance [Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS)], hope [Adult Hope Trait Scale (AHTS)], and optimism [Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R)].

Results

Regression analysis found that a higher perception of benefits of the disease (benefit findings) and a greater effort to regulate feelings of distress (distress regulation) explained 67.1 % of the variance of PTG.

Conclusions

There were no significant differences in the level of PTG in terms of demographic indicators, type of cancer, current state of disease, or type of treatment. It was found that it was important for patients to perceive that their disease had been beneficial in a certain way. It was also important that patients made a great effort to regulate distress, which can occur when coping with the negative consequences of a disease, and at the same time, it is important for the process of PTG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Oncological diseases are the most dreaded and most traumatic of diseases and have an effect on the physical, mental, and spiritual life of a patient [7]. In the fourth edition of the DSM-IV, cancer was included among the stressors that can cause posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [30]. PTSD occurs after an emotionally difficult or stressful event that is beyond normal human experience and is traumatic for most people [22]. It is delayed and is a sustained reaction to a stressful situation or event which has an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic character. The manifestations of PTSD are often dramatic with people losing enthusiasm for work and having problems with personal relationships and problems with enjoying life [23]. Over the last 20 years, there has been an increasing scientific interest not only in the research of the negative impact of traumatic events but also in the research of positive changes, which can occur after the struggle with trauma [33]. Several authors [2, 20, 32, 35] state that after a person experiences a traumatic event, they can get above their pretraumatic functional level. This phenomenon has been named posttraumatic growth (PTG) [32]. PTG is defined as a significant positive change in the cognitive and emotional life of an individual, which can have external manifestations. The growth means a change in which an individual gets above the pretraumatic level of adaptation, psychological functioning, and understanding of life. The term is the deliberate opposite to “posttraumatic stress disorder” and emphasizes that the change is positive while the person is truly transformed [31]. However, PTG does not appear in everybody who survives a traumatic event. Calhoun and Tedeschi [3] state that the prevalence of PTG is mostly referred to in two points: 30–40 and 60–80 %. Tedeschi and Calhoun [33] stress that PTG is not a direct consequence of trauma. They state that PTG is the positive change which results from the “struggle” with the traumatic event. PTG occurs at the same time as attempts to adapt to a set of negative circumstances which can further increase levels of distress. Therefore, PTG and distress are often together in coexistence [33]. In oncological diseases in particular, there is often a coexistence between positive and negative emotions. Thus, it is difficult to connect the high score in PTG with the low score in anxiety scales and also with high scores in questionnaires which measure quality of life [34]. Sumalla et al. [30] state that cancer and its treatment have specific characteristics which distinguish it from other traumas. These characteristics could have an impact on the incidence of PTG. The first is the group of stressors—the interaction of many stressors (e.g., diagnosis, severity and prognosis of the disease, aggressive nature of the treatment, changes of physical appearance, decrease of functional autonomy, changes in life roles). The second is the inner nature of the disease: it is not possible to remove what is associated with the trauma (e.g., required hospital visits, repeated examinations, and tests). In comparison to other types of trauma in which the sources of stress are mostly external and avoidance behavior is possible, cancer has also an inner nature and genesis. The internal nature of this stressor could play a key role in changing assumptions about self. The third is the ruminations and sense of foreshortened future: the subject loses expectations about the future [5] and, even after successful treatment, there remains uncertainty that a relapse can occur [11]. These feelings disrupt a subject’s goals, which is another condition for PTG. Patients with cancer or HIV/AIDS are faced with the fear that the disease can reemerge and proceed to shorten their lives. These fears can lead to a change of priorities and lead to different values and access to everyday life [25]. The fourth is chronicity: it is not easy to determine the exact start and end of a traumatic event, and in cancerous diseases, it is more like a “long running hurdles” [30]. Due to the increasing effectiveness of treatment, cases can be oncological disease included to the chronic diseases [6]. Guľášová [7] states that for chronic diseases, it is characteristic that personality changes are often negative with regard to the changed and restrictive situation. She further states that it is well known that a physical defect may become, in favorable circumstances, the source of energy and impulse to achieve unusual success. The disease is often an opportunity to review prior life and make possible changes to life interests and attitudes.

Several authors [1, 2, 9, 10, 13, 16, 21, 27, 30, 37] have noted the presence of PTG in patients with cancer. It has been found that the main factors that could influence the level of PTG in cancer are age, with younger patients having lower levels of PTG in all areas [1, 13], time since the cancer had been diagnosed [13], accepted emotional support (especially during the first months) [27], instrumental support, positive reframing and humor [26], optimism and hope [10], and the process of sense making and benefit finding [34].

The aim of the current research was to identify the occurrence of PTG and to find out its level in patients with cancer. The study also aimed to discover if there were differences in the level of PTG in terms of demographic indicators and characteristics of the disease and treatment. Furthermore, it aimed to examine if there was a significant link between PTG and the perceived benefits of the disease, dispositional optimism, hope, and distress tolerance.

Methods

Procedure and participants

The data were collected in the National Oncological Institute (NOU) and in the Clinic of Hematology and Onco-Hematology. It was decided to choose a particular type of oncological disease mainly due to the internal consistency of the selected group. The selection criterion was hematologic oncological disease and, particularly, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, and leukemia. The next selection criterion was the period of time since the disease had been diagnosed. It had to have been at least 6 months since the patient had learned about the diagnosis. The data collection was carried out in cooperation with the doctors and nurses. The questionnaires were filled in with patients during regular medical examinations or during outpatient chemotherapy. The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the directors of the medical institutes, and patients had the choice to participate in the research or not. The total number of patients was 72 [35 men (48.6 %) and 37 women (51.4 %)], with the average age of 48 (SD = 14.6; range = 18–77). Other demographic and clinical information about participants are shown in Table 1.

Measures

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) is the main method used to measure PTG [32]. In this research, a Czech translation of the questionnaire was used [24]. The questionnaire consists of 21 items which measure five factors: relationships with others (α = 0.877), new possibilities (α = 0.821), personal strength (α = 0.828), spiritual change (α = 0.874), and appreciation of life (α = 0.757). The respondents commented on the 21 items and, on a six-level scale, stated to what extent they had experienced certain change as a result of the disease ranging from 0 (I have not experienced such change) up to 5 (I have largely experienced such change). The total score can range from 0 up to 105 with a higher score indicating higher PTG. The inner consistency of all the questionnaires was α = 0.937.

The Benefit Finding Scale for Children-Czech version (BFSC-CZ) measures one factor which is the perceived benefit of the disease. It consists of ten items which are answered on a five-point scale from 1 (disagree) up to 5 (agree). Despite the scale being originally developed and used for pediatric cancer patients (the majority of children were aged 15–16), experience suggests that its use is broader. It has also been successfully used in adult patients with scoliosis [14]. The inner consistency in this current research was α = 0.881.

The Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS) is a scale measuring the ability to tolerate psychical distress or resist negative experience and negative psychical states [28]. The scale of anxiety tolerance consists of 15 items which is comprised of four factors: perceived ability to tolerate distress (α = 0.720), subjective appraisal of distress acceptability (α = 0.680), absorption by the distress (α = 0.909), and regulation of distress feelings (α = 0.880). The respondents express their consent on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) up to 5 (strongly disagree). Higher scores mean a better ability to tolerate higher levels of distress.

The Adult Hope Trait Scale (AHTS) is a method used to measure hope. The Slovak version of the Snyder scale of hope was used [8]. It consists of 12 items and measures two subscales: agency thinking (α = 0.710) and pathway thinking (α = 0.608). Respondents answer on a four-level scale from 1 (completely false) up to 4 (completely right). The total score can range from 8 to 32. Both the components are evaluated individually as well as hope itself which is done by adding the results of the two components. The internal consistency for all the questionnaires within this research was α = 0.795.

The Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) is the method used to measure dispositional optimism. It consists of ten items from which only six items are scored and four items not scored. Some authors state that this method measures only optimism, while other authors state that it measures optimism and also pessimism [29]. In this research, only optimism was measured. Respondents answer on a five-level scale from 1 (strongly disagree) up to 5 (strongly agree). The total score can range from 6 up to 30 with higher scores indicating higher optimism. The internal consistency for this survey was α = 0.703.

Results

Descriptive analysis

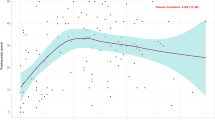

The descriptive statistics of posttraumatic growth and its domains by type of cancer are shown in Table 2. PTG scores for each type of cancer are also shown in Fig. 1.

Analysis of differences

There were no statistically significant differences found in the level of posttraumatic growth among patients in terms of demographic indicators (gender, marital status, and education) and characteristics of disease (type of disease, current state of the disease, type of undergone treatment, and current state of treatment). The differences in PTG and its domains between different types of cancer are not statistically significant, but the level of PTG and its domains varies quite a lot between these subgroups (Table 2, Fig. 1). The results of the differences in PTG and its domains between men and women are shown in Table 3.

Correlation and regression analysis

The results of the correlation analysis between posttraumatic growth and other variables are shown in Table 4. A significant positive relationship was found between PTG and benefit finding, pathway thinking and optimism, as well as between pathway thinking and benefit finding, optimism and agency thinking, between optimism and agency thinking, optimism and tolerance distress, and between tolerance of distress and absorption and appraisal of distress. A significant negative relationship was found between posttraumatic growth and regulation of distress.

The results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 5. In the case of the frequency of posttraumatic growth, the multiple hierarchical linear regression, a stepwise method, showed that two of the tested predictors were significant: regulation of distress and benefit findings of the disease.

The regulation of distress explained 20.2 %, and benefit finding explained 69.2 % of the variance in the frequency of posttraumatic growth. Patients who found more benefit from their disease (b = 2.058) and made a great effort to regulate the feelings of distress (b = −1.615) achieved a higher level of posttraumatic growth.

Discussion

This study examined the level of PTG in patients with oncological diseases. Most patients split their lives into life before and after the trauma and reported some positive changes as a result of their cancer. However, there were neither statically significant differences found in the level of PTG between the compared groups in terms of demographic indicators nor characteristics of the onco-hematological disease. The period of time since a patient had been diagnosed did not show itself to be a significant indicator in relation to the overall level of PTG but had a significantly positive relationship in the area of new possibilities. The regression analysis showed that benefit finding, regulation of distress, and comprehensibility were statistically significant in explaining the variance of PTG frequency.

Several authors [18, 36, 38] have noted that women tend to have a greater level of PTG than men. This study also found that women had higher PTG (M = 69.51) than men (M = 68.57), but the difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, as far as demographic characteristics such as marital status and education were concerned, no significant statistical differences were discovered between the compared groups. Similarly, no significant statistical differences were discovered as far as the disease and treatment were concerned. Despite no statistically significant differences, the level of PTG varied between the different types of hematological cancer. With regard to the relationship between PTG and type of cancer, the subjective appraisal of cancer severity could be important. In the cancer type which had higher levels of PTG, many patients may perceive it more severely. However, it is hard to assess in this study because of the size of subgroups by type of cancer. There is a paucity of studies in which the relationship between PTG and type of cancer has been studied. Therefore, further studies are needed with more participants in groups with different types of cancer. In further research, it could also be interesting to analyze the prognosis of disease, level of distress, and perceiving severity of each studied type of cancer.

However, the study did highlight that the more a patient could perceive the benefit of the disease, the higher the level of PTG. It seems that an ability to identify benefits which the disease has brought is important for experiencing PTG. De Groot [6] states that finding benefits allows a positive reevaluation of the traumatic event. Thornton [34] sees benefit findings as a process which helps to recover the concept of self. A positive relationship between the perceived benefit and PTG was also found by Mols et al. [17].

Several authors [3, 19, 33] claim that if PTG is to occur, an individual must experience more significant distress. However, Calhoun and Tedeschi [3] also state that if the level of distress is too high, either PTG does not occur or the cognitive mechanisms important to process the event are disrupted. This study found that the more the patient had to make an effort to regulate distress, the higher the level of PTG was. In the process of posttraumatic growth, it is important that patients should feel that situations are distressing and should be active in the consequent action to either avoid or immediately attenuate the distressing experience. Likewise, Calhoun et al. [4] state that if the traumatic event does not shatter core beliefs and assumptions about the world and if people do not perceive the situation as distressing, the process of PTG cannot start. Kashdan and Kane [12] found that for incidences of PTG in people after traumatic events, it is important that they experience distress. However, they also found that in the distress-PTG relationship, it is important how people cope with distress which is present after trauma. They found that if people cope with this distress by experiential avoidance, they subsequently experience low levels of PTG. For PTG, it is important that a patient experiences feelings of distress for some time, but patients should also know how to regulate the distress which is present in the presence of a traumatic situation and subsequently cope with it.

This study assumed that the occurrence of PTG or its level could be indirectly influenced by pathway thinking by means of a positive relationship to the perceived benefit. This proved to be a significant predictor of PTG. Pathway thinking is the ability to generate one or more functional ways to reach a goal. This could presumably help a patient adapt better to the changed world in view of their disease. As a result of this, a patient could probably perceive not only the negative side of the disease but also its possible benefits, and thus, a higher level of PTG could subsequently occur. Ho et al. [10] even claim that hope (agency and pathway thinking) together with dispositional optimism partake in the explanation of 25 % of PTG variance. While this study discovered that dispositional optimism is not directly related to PTG, it found that optimism was positively related to both parts of hope. Hope is positively related to benefit finding which is an important predictor of PTG. Through this relationship to hope, it seems that optimism can have some indirect influence on PTG.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The research was limited by the size of the sample and also by application of multiple research tools used for measuring. Even though we tried to deal with patients with empathy and sensitive manners during the psychological examination, they could find answering our questions during examination process an exhausting and tiring process. Their attention and concentration could have been undermined, which could distort their answers. Since the nature of some questions imply a deeper reflection over the subject and some of the questions even ask for positive aspects of the disease, which is not a common approach and thus may confuse the patient, we recommend to include a smaller amount of research tools or to divide examinations into several sessions in the future to obtain more accurate results. Another limit of the research might have been the environmental conditions of the data collection which may have affected the scores obtained. During the interviews, the patients were approached sensitively and with respect for their difficult situation, but especially patients, who were interviewed during outpatient chemotherapy, could feel some distress due to the procedure. The final limitation could also be the way of examining PTG which was based on a subjective assessment of changes. Despite the importance of the subjective assessment of positive changes, it would have been useful to confirm the presence of these changes through people who were familiar with the patient such as parents, spouses, or closest friends [15]. This study managed to highlight not only the negative changes which occur in patients with oncological disease but also the positive ones. It also tried to examine which factors could be related to the occurrence of PTG in the patients. The study could have also concentrated on the level of other constructs according to PTG theory such as social support, the occurrence of posttraumatic symptoms, or to what extent the presence of such phenomenon is important and stressful at the same time. Longitudinal research could also be interesting for future studies. The results of this research can be both an impetus for further research and practical purposes such as the creation of an intervention program. This would focus on the ability of a patient to control distress or at teaching patients to search for available resources to cope with their problem.

References

Barakat LP, Alderfer MA, Kazak AE (2006) Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. J Pediatr Psychol 31:413–419

Barskova T, Oesterreich R (2009) Post-traumatic growth in people living with a serious medical condition and its relations to physical and mental health: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 31:1709–1733

Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG (2006) Handbook of posttraumatic growth: research and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah

Calhoun LG, Cann A, Tedeschi RG (2010) The posttraumatic growth model: sociocultural considerations. In: Weiss T, Berger R (eds) Posttraumatic growth and culturally competent practice. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 1–15

Cansler L (2010) PTSD and sense of foreshortened future. http://www.suite101.com/content/ptsd-and-a-sense-of-a-foreshortened-future-a225852. Accessed 12 Apr 2010

De Groot J (2008) Cancer, trauma and personal growth, addressing subjective response to cancer. Oncol Exch 7:28–33

Guľášová I (2009) Telesné, psychické, sociálne a duchovné aspekty onkologických ochorení. Osveta, Martin

Halama P (2001) Slovenská verzia snyderovej škály nádeje: Preklad a adaptácia. Česk Psychol 45:135–141

Hefferon K, Grealy M, Mutrie N (2009) Posttraumatic growth and life threatening physical illness: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Br J Health Psychol 14:343–378

Ho S, Rajandram RK, Chan N, Summan N, McGrath C, Zwahlen RA (2011) The roles of hope and optimism on posttraumatic growth in oral cavity cancer patients. Oral Oncol 47:121–124

Jaarsma TA, Pool G, Sanderman R, Ranchor VA (2006) Psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the posttraumatic growth inventory among cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 15:911–920

Kashdan TB, Kane JQ (2011) Post-traumatic distress and the presence of post-traumatic growth and meaning in life: experiential avoidance as a moderator. Personal Individ Differ 50:84–89

Manne S, Ostroff J, Winkel G et al (2004) Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: patient, partner, and couple perspective. Psychosom Med 66:442–454

Mareš J, Ježek S, Kreminová M (2007) Přínos nemoci z pohledu nemocných dětí. In: Mareš J, Dittrichová J, Doulík P et al (eds) Kvalita života u detí a dospievajúcich II. MSD, Brno, pp 215–223

Mareš J (2009) Posttraumatický rozvoj: výzkum, diagnostika, intervence. Česk Psychol 53:271–290

Mitchell J (2007) Finding positive meaning in the experience of breast cancer. CSW Update 2:7–9

Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, Van de Poll-Franse LV (2009) Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health 24:583–595

Morris BA, Shakespeare-Finch J (2011) Cancer diagnostic group differences in posttraumatic growth: accounting for age, gender, trauma severity, and distress. J Loss Trauma 16:229–242

Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E et al (2008) Personal growth and psychological distress in advanced breast cancer. Breast 17:382–386

Park CL, Cohen LH, Murch RL (1996) Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. J Pers 64:72–105

Park CL, Edmondson D, Fenster JR, Blank TO (2008) Meaning making and psychological adjustment following cancer: the mediating roles of growth, life meaning, and restored just-world beliefs. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:863–875

Praško J (2002) Úzkostné poruchy. In: Höschl C, Libiger J, Švestka J (eds) Psychiatrie. Tigis, Praha, pp 513–518

Praško J, Hájek T, Pašková B et al (2003) Stop traumatickým vzpomínkam. Portál, Praha

Preiss M, Krutiš J, Mareš J (2008) Česká verze dotazníku PTGI (pracovní verze). Praha, Hradec Králové

Sawyer A, Ayers S, Field AP (2010) Posttraumatic growth and adjustment among individuals with cancer or HIV/AIDS: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 30:436–447

Schroevers MJ, Teo I (2008) The report of posttraumatic growth in Malaysian cancer patients: relationships with psychological distress and coping strategies. Psycho-Oncology 17:1239–1246

Schroevers MJ, Helgeson VS, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV (2010) Type of social support matters for prediction of posttraumatic growth among cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 19:46–53

Simons JS, Gaher RM (2005) The distress tolerance scale: development and validation of a self-report measure. Motiv Emot 29:83–102

Snyder CR, Lopez SJ (2007) Positive psychology: the scientific and practical exploration of human strengths. Sage, London

Sumalla EC, Ochoa C, Blanco I (2009) Posttraumatic growth in cancer: reality or illusion? Clin Psychol Rev 29:24–33

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (1995) Trauma and transformation: growing in the aftermath of suffering. Sage, London

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (1996) The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 9:455–471

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (2004) Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq 15:1–18

Thornton AA (2002) Perceiving benefits in the cancer experience. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 9:153–165

Vázquez C, Hervás G, Ho MY (2006) Intervenciones clínicas basadas en la psicología posititiva: Fundamentos y aplicaciones. Psicol Conduct 14:401–432

Vishnevsky T, Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, Demakis GJ (2010) Gender differences in self-reported posttraumatic growth: a meta-analysis. Psychol Women Q 34:110–120

Waltson J (2002) Growing through cancer. Cure Magazine, Survivors Issue. http://www.healingfocus.org/articles/GrowingThroughCancer.pdf. Accessed 9 Apr 2010

Zwahlen D, Hagenbuch N, Carley MI, Jenewein J, Buchi S (2009) Posttraumatic growth in cancer patients and partners-effects of role, gender and the dyad on couples’ posttraumatic growth experience. Psycho-Oncology 19:12–20

Disclosures

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baník, G., Gajdošová, B. Positive changes following cancer: posttraumatic growth in the context of other factors in patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer 22, 2023–2029 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2217-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2217-0