Abstract

Goal

This study was to objectively assess the effect of music therapy on patients with advanced disease.

Patients and methods

Two hundred patients with chronic and/or advanced illnesses were prospectively evaluated. The effects of music therapy on these patients are reported. Visual analog scales, the Happy/Sad Faces Assessment Tool, and a behavior scale recorded pre- and post-music therapy scores on standardized data collection forms. A computerized database was used to collect and analyze the data.

Results

Utilizing the Wilcoxon signed rank test and a paired t test, music therapy improved anxiety, body movement, facial expression, mood, pain, shortness of breath, and verbalizations. Sessions with family members were also evaluated, and music therapy improved families’ facial expressions, mood, and verbalizations. All improvements were statistically significant (P<0.001). Most patients and families had a positive subjective and objective response to music therapy. Objective data were obtained for a large number of patients with advanced disease.

Conclusions

This is a significant addition to the quantitative literature on music therapy in this unique patient population. Our results suggest that music therapy is invaluable in palliative medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Music and medicine have been interrelated in many cultures throughout history. Music is experienced throughout the entire life cycle particularly at seminal events, i.e., birth, marriage, and death. It has been used to celebrate and honor special occasions and milestones. It has the ability to communicate in a way that transcends language. Music is capable of transforming and moving individuals emotionally. It has been used to heal individuals physically, psychologically, socially, emotionally, and spiritually.

The literature regarding the use of music with the terminally and/or chronically ill has continued to grow. Music has been used therapeutically in hospice [8, 11, 10], in palliative care [5, 14–19, 24, 25], while receiving radiation therapy [27], during chemotherapy [17, 23, 27–29], and undergoing medical procedures (such as port placement/removal or tissue biopsy) [12, 20]. Music has been used in symptom management such as for pain [2, 10–14, 16, 30, 34] and anxiety [1, 2, 11, 12, 14, 16, 23, 27, 30] and has been associated with improved quality of life [5, 9] and spiritual healing [14, 19, 21, 25, 30].

Most published studies are qualitative and/or case studies. Quantitative trials measuring the benefits of music therapy are less common. In reviewing the literature, only 15 studies [1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 20, 23, 24, 27–30] included objective measurement of music therapy effectiveness with cancer patients. Therefore, we have sought to add this to the quantitative literature in this study. For this study, data were prospectively gathered from 200 patients and are reported.

Methods

Patient selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Patients admitted to The Harry R. Horvitz Center for Palliative Medicine and those patients followed by the Palliative Medicine consult service on other acute units at Cleveland Clinic Foundation (CCF) were eligible to participate in this study. Some patients were offered music therapy services but declined them.

Referrals for music therapy were directly requested by a physician on a standardized physician’s order sheet or by verbal request from the social worker, physician assistant, nurses, or other members of the interdisciplinary team. Indirect referrals involved inquiries based on information provided in daily morning report. Brochures on music therapy were routinely included within the admission packet patients received during their stay on the unit, and on occasion, patients and families directly requested services themselves.

Sessions

Music therapy was done by a board-certified music therapist or a music therapy intern under the direction of the board-certified music therapist. Each session included assessment and intervention. The goals of music therapy were determined based on the patient’s subjective needs, as well as those perceived by the therapist [6]. A variety of patient goals were derived (see results in Table 9 for a list), with multiple goals being addressed within the same session. Goals were also designed to address the needs of family members present during the session. As with the patient goals, these were individualized and multiple goals were addressed as needed within the same session. Once goals were established, the therapist individualized interventions designed to meet these goals. A description of these interventions (in order of frequency) can be found in Table 1. The patient’s comfort and fatigability level were taken into consideration, and the patient was encouraged to participate as he/she was able. Family members present in the room were also encouraged to participate in the session. Multiple interventions were often presented within the same session.

Data collection

During the first meeting with a patient, a music therapy assessment was completed. This included information on the patient’s musical background (played instrument, sang, type of performing group) and musical preferences (styles, favorite songs, and favorite artists/groups). Demographic information was collected.

At the beginning of each session and immediately after the completion of all music therapy interventions, the patient was presented with the Rogers’ Happy/Sad Faces Assessment Tool [22], a scale of five faces that was used to identify mood before and after music therapy. Visual analog scales were used to measure symptoms before and after music therapy. Symptoms were anxiety, depression, pain, and shortness of breath. A behavioral scale adapted from the Riley Infant Pain Scale [26] and the Nursing Assessment of Pain Intensity [26] was utilized by the music therapist involving patients’ facial expression, body movement, sleep, and verbalizations/vocalizations.

Data were recorded on a standardized data collection form, approved and copyrighted by the Cleveland Clinic Forms Committee for inclusion in the patient’s chart. In addition to the before/after data listed above, other information recorded included the following: date, time spent, goals, interventions, type of participation, style of music and songs used, status of goals (met, unmet, unable to determine), patient consenting to a repeat session with therapist, family member(s) present, patient’s verbal response, and family member(s)’ verbal response. A narrative comment section was also provided so that any pertinent information not fitting in the other sections could be included.

A computerized database was designed for standardized collection of data. FileMaker Pro (Santa Clara, CA) was used to maintain this database. These data were then downloaded into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Redmond, Washington) and statistical analysis was performed. The Wilcoxon signed rank test and a paired t test were used to determine if patient (or family) assessment and therapist assessment scores significantly changed following music therapy, with P<0.05 indicating statistical significance. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to study score changes between variables such as gender and being a musician. Spearman’s correlation was calculated between age and score changes, and between age and percentage of goals met.

Results

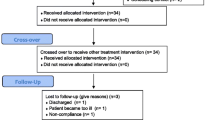

Patients

An ex post facto study of the data gathered from September 2000 to August 2002 was completed. During this time, 345 patients were seen, for a total of 396 sessions. For this particular study, however, it was decided that only the data gathered in the initial sessions would be analyzed. In 199 of 200 sessions, music therapy services were in the patient’s room on the Harry R. Horvitz Center for Palliative Medicine, and the other session was provided in a patient room on the Colorectal Surgery Unit. This patient was being seen by the Palliative Medicine consult team, and the music therapist was also asked to see the patient. Of 200 patients, 159 sessions took place in private rooms and 41 in double occupancy rooms. There were 200 initial sessions performed that involved a patient and music therapist planned intervention and postintervention evaluation. Of these 200 patients, 59% were female. The median age was 62 years (range 24–87 years). Diagnoses included malignancies, nonmalignant syndromes, pain disorders, sickle cell disease, aortic aneurysm, Gardner’s syndrome, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), other neurodegenerative disorders, and other life-limiting illnesses. Only 29% of patients had a musical background (former or current singer or player of an instrument).

The results of score changes during the music therapy session are in Table 2. Patient-rated scores for anxiety, mood, pain, and shortness of breath improved significantly (Tables 3 and 4). Facial expression, movement, and verbalizations all improved significantly (P<0.001) following music therapy (Tables 5 and 6). Although sleep was included in the behavioral scale, it was not investigated as assisting the patient in relaxing and falling asleep was only addressed in 12 sessions.

Results following music therapy were compared between female and male patients, and the only significant difference was changes in the facial score. In looking at other variables of musicianship and age, there were no differences between patients with musical background and those who did not have a musical background, and percentage of goals met was the only variable correlated with age. Reasons for referral (Table 7), styles of music used (Table 8), goals addressed (Table 9), interventions presented (Table 10), and patient response to the intervention were also investigated.

Families

Family members were present in 68 of the 200 sessions. The median number of family members present was 1 (range of 1–4). Family members also benefited. Mood scores of family members improved significantly (P<0.001). The only family rating that did not improve postintervention was anxiety (P=0.50).

Facial expression and verbalization improved significantly (P<0.001), but body movement did not improve (P=1.00). Sleep was not investigated in family members. Styles of music used (Table 8), goals addressed (Table 9), interventions presented (Table 10), and family response to the intervention are also reported.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to objectively assess music therapy for such a large number of patients with advanced disease. This will add to the quantitative and objective data in the study of this unique patient population. The computerized database has been invaluable, as it has enabled the music therapist to maintain and analyze large amounts of data.

Individual symptoms such as anxiety, depression, pain, and shortness of breath were clinically better after music therapy intervention. Statistical analysis of the data was performed twice using two different tests, and statistical significance was still found. Although the percentage of goals met was correlated with age, the correlation was very weak. Therefore, even though it was statistically significant, it may not be very clinically meaningful. It is possible that as individuals mature, goals are more specific and defined. Also, there was no statistical difference with patient scores whether they had a musical or non-musical background. This proves that music is a universal language, and individuals need not have special training to appreciate or benefit from it.

The results for families regarding movement and anxiety were not as statistically significant as those for patients. In the future, anxiety should be consistently evaluated in family members. The anxiety scale was evaluated in only seven family members. Such a small number would make results insignificant. In general, few family members were present and therefore participated in music therapy sessions. Therapist perceived benefits defined by body movement did not improve. Further investigation into the benefits of music therapy on depression and mood among family members may also be worthwhile.

This study also demonstrated that music therapy had a positive effect on patients’ and families’ mood, as well as benefit confirmed through facial expression and verbalizations of both. A key element to the music therapy session is that of presence, having someone with the ability to listen to the patient. Factors that may contribute to this include the following: (1) the music itself, (2) the fact that someone is attending to the patient, (3) the therapeutic relationship between patient and therapist, or (4) a combination of any of these factors. Future studies can be designed and separate these factors to determine which variable contributed to the effectiveness of the interventions.

There are some limitations to this study. The music therapist was also the collector of data, and thus, the findings could have been biased. While the therapist attempts to remain objective, it is possible that patients may respond favorably to please the therapist. To avoid this bias, it is recommended that whenever possible, someone other than the music therapist present the scales before and after the intervention for data collection. Although all eight parameters were found to be statistically significant, there were overlapping standard deviations. The behavioral scales were a category scale with only four divisions. The validity (clinical significance) of differences is yet to be determined. It is possible that a score improvement by one point is relevant, but further study is needed to define statistical and clinical significance. Reliability (test and retest consistency) may also be a bias since this may influence results. More importantly, the duration of the effect of music therapy is also unknown, presenting another opportunity for future investigation.

As reported in a previous article [6], a similar database has been used at our Hospice (of Cleveland Clinic), and it is hoped that a future study will include a comparison of the impact of music therapy between hospice and palliative medicine patients. Future research should investigate the data from multiple sessions for the same patient to determine if the benefit of music therapy increases with experience over time. Evaluating the impact of music therapy against placebo is being considered for a future research project. The effectiveness of specific interventions when addressing specific goals should also be investigated. This would help determine the most effective interventions to utilize when addressing specific problems.

Conclusion

Most patients and families who participated had a positive response to music therapy, and the results demonstrated the effectiveness of music therapy. Since music therapy had a significant effect on common symptoms of patients with chronic and/or terminal illness, such as pain, anxiety, depression, and shortness of breath, it is suggested that music therapy would be an asset to palliative medicine programs.

References

Bailey LM (1983) The effects of live music versus tape-recorded music on hospitalized cancer patients. Music Ther 3:17–28

Bailey LM (1984) The use of songs in music therapy with cancer patients and their families. Music Ther 4:5–17

Beck SL (1991) The therapeutic use of music for cancer-related pain. Oncol Nurs Forum 18:1327–1337

Curtis SL (1986) The effect of music on pain relief and relaxation of the terminally ill. J Music Ther 23:10–24

Daveson BA (2000) Music therapy in palliative care for hospitalized children and adolescents. J Palliat Care 16:35–38

Gallagher LM, Steele AL (2001) Developing and using a computerized database for music therapy in palliative medicine. J Palliat Care 17:147–154

Gallagher LM, Huston MJ, Nelson KA, Walsh D, Steele AL (2001) Music therapy in palliative medicine. Support Care Cancer 9:156–161

Hilliard RE (2001) The use of music therapy in meeting the multidimensional needs of hospice patients and families. J Palliat Care 17:161–166

Hilliard RE (2003) The effects of music therapy on the quality and length of life of people diagnosed with terminal cancer. J Music Ther 40:113–137

Krout RE (2001) The effects of single-session music therapy interventions on the observed and self-reported levels of pain control, physical comfort, and relaxation of hospice patients. Am J Hospice Palliat Care 18:383–390

Krout RE (2003) Music therapy with imminently dying hospice patients and their families: facilitating release near the time of death. Am J Hospice Palliat Care 20:129–134

Kwekkeboom KL (2003) Music versus distraction for procedural pain and anxiety in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 30:433–440

Magill L (2001) The use of music therapy to address the suffering in advanced cancer pain. J Palliat Care 17:167–172

Munro S, Mount B (1978) Music therapy in palliative care. Can Med Assoc J 119:1029–1034

O’Callaghan CC (1995) Songs written by palliative care patients in music therapy. In: Lee CA (ed) Lonely waters. Sobell Publications, Oxford, pp 31–40

O’Callaghan CC (1996) Pain, music creativity and music therapy in palliative care. Am J Hospice Palliat Care 13:43–49

O’Callaghan CC (1999) Lyrical themes in songs written by palliative care patients. In: Aldridge D (ed) Music therapy in palliative care: new voices. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, pp 43–58

O’Callaghan C (2001) Bringing music to life: a study of music therapy and palliative care experiences in a cancer hospital. J Palliat Care 17:155–160

O’Kelly J (2002) Music therapy in palliative care: current perspectives. Int J Palliat Nurs 8:130–136

Pfaff VK, Smith KE, Gowan D (1989) The effects of music-assisted relaxation on the distress of pediatric cancer patients undergoing bone marrow aspirations. Child Health Care 18:232–236

Robertson-Gillam K (1995) The role of music therapy in meeting the spiritual needs of the dying person. In: Lee CA (ed) Lonely waters. Sobell Publications, Oxford, pp 85–98

Rogers A (1981) In: Third world congress on pain of the international association for the study of pain, Edinburgh, Scotland, September 4–11, 1981, Abstracts. Pain, suppl 1, pp S1–S319

Sabo CE, Michael SR (1996) The influence of personal message with music on anxiety and side effects associated with chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 19:283–289

Salmon D (1995) Music and emotion in palliative care: accessing inner resources. In: Lee CA (ed) Lonely waters. Sobell Publications, Oxford, pp 71–84

Salmon D (2001) Music therapy as psychospiritual process in palliative care. J Palliat Care 17:142–146

Schade JG, Joyce BA, Gerkensmeyer J, Keck JF (1996) Comparison of three preverbal scales for postoperative pain assessment in a diverse pediatric sample. J Pain Symp Manag 12:348–359

Smith M, Casey L, Johnson D, Gwede C, Riggin OZ (2001) Music as a therapeutic intervention for anxiety in patients receiving radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 28:855–862

Standley JM (1992) Clinical applications of music and chemotherapy: the effects of nausea and emesis. Music Ther Perspect 10:27–35

Weber S, Nuessler V, Wilmanns W (1997) A pilot study on the influence of receptive music listening on cancer patients during chemotherapy. Int J Arts Med 5:27–35

Zimmerman L, Pozehl B, Duncan K, Schmitz R (1989) Effects of music in patients who had chronic cancer pain. West J Nurs Res 11:298–309

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of The Kulas Foundation and The Music Therapy Program Fund. We thank Lisa Rybicki, MS, for performing the statistical analysis and Becky Michel and Lisa McKelvey, music therapy interns, for their contributions to the sessions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallagher, L.M., Lagman, R., Walsh, D. et al. The clinical effects of music therapy in palliative medicine. Support Care Cancer 14, 859–866 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0013-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0013-6