Abstract

Background

Aim of the present systematic review is to compare the postoperative outcomes after minimally invasive anterior and posterior component separation technique (CST), in terms of postoperative morbidity and recurrence rates.

Methods

Nine-hundred and fifty-nine articles were identified through Pubmed database. Of these, 444 were eliminated because were duplicates between the searches. Of the remaining 515 articles, 414 were excluded after screening title and abstract. One hundred and one articles were fully analysed, and 73 articles were further excluded, finally including 28 articles. Based on the surgical technique, three groups were created: Group A, endoscopic anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparotomy; Group B, endoscopic anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline laparoscopically or robotically; Group C, laparoscopic or robotic posterior CST with transversus abdominal muscle release (TAR).

Results

In group A, B and C, 196, 120 and 236 patients were included, respectively. Surgical and medical complication rates for the three groups were 31.2% and 13.7% in group A, 15.8% and 4.1% in group B, and 17.8% and 25.4% in group C, while recurrence rate was 10.7%, 6.6% and 0.4%, respectively. Statistically significant differences were observed in terms of surgical postoperative complication rate between group A versus B (p = 0.0022) and between group A versus C (p = 0.0015) and of recurrence rate between group A versus C (p = < 0.0001) and B versus C (p = 0.0009).

Conclusions

Anterior CST with midline closure by laparotomy showed the worst results in terms of postoperative surgical complications and recurrence in comparison to the pure minimally anterior and posterior CST. Posterior CST-TAR showed lowest hospital stay and recurrence rate, although the follow-up is short. However, due to the poor quality of most of the studies, further prospective studies and randomized control trials, with wider sample size and longer follow-up are required to demonstrate which is the best surgical option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Large abdominal wall defect reconstruction is a challenge for surgeons [1]. To solve this problem successfully by surgery, anatomical and tension-free restoration of the abdominal wall before its closure are mandatory [1, 2].

For this purpose, Ramirez et al. in 1990, first described the so-called component separation technique (CST) which provides the division of the posterior rectus sheath and the release of the external oblique aponeurosis opening the space between the external and the internal oblique muscles, by an anterior approach [3]. However, due to the division of abdominal wall perforators, several wound complications as seromas, flap necrosis and subcutaneous abscesses have been reported with the use of the open CST (OCST) [4,5,6]. For this reason, with the aim to improve the vascularization of the skin flap and consequently reduce these postoperative complications, Lowe et al. [7], in 2000 proposed the endoscopic CST (ECST), showing better postoperative results if compared to the open approach [1, 7].

On the other hand, in 2012, Novitsky et al. first described the posterior CST with transversus abdominal muscle release (TAR) [8]. The goal of this technique is to achieve the retromuscular space, after opening the posterior rectus sheath, dissecting the transversus abdominal muscle that is divided at its medial border, to reach the space between the muscle and the trasversalis fascia and preserve the neurovascular bundles close to the linea semilunaris [2, 8]. Such as the anterior CST, it was proposed to combine the advantages of a CST with the minimally invasive approach to reduce the postoperative morbidity and increase the TAR length [9].

This systematic review was carried out with the intention of reporting which is the best minimally invasive CST, in terms of postoperative complication and recurrence rates, comparing the postoperative outcomes after anterior CST and posterior CST with TAR.

Materials and methods

Institutional review board approval and informed consent from participants are no need for this systematic review.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) articles from any country written in English, Spanish or Italian; (2) articles about minimally invasive anterior or posterior CST, including endoscopic, laparoscopic and robotic approach, for the treatment of the abdominal wall defects; and (3) articles reporting postoperative complications and/or recurrence after anterior or posterior minimally invasive CST.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were: (1) articles reporting open anterior or posterior CST; (2) articles reporting both minimally invasive and open CST in which was not possible to extract only data regarding the minimally invasive approach; (3) articles reporting hybrid TAR; (4) articles obtained from the same sample of patients, from which one article has already been included; (5) articles reporting posterior CST without TAR; (6) reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, studies with data retrieved from registries, comments, case reports, correspondence and letters to authors or editors, editorials, technical surgical notes, and imaging studies; and (7) articles involving animals.

Search strategy

A systematic review of published papers was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [10]. The search was carried out in the PubMed database, using the keywords reported in Table 1.

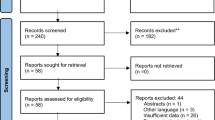

The search revealed 959 articles published between December 1982 and February 2019. Of these, 444 were eliminated because there were duplicates between the searches. Of the remaining 515 articles, 414 were excluded after screening the title and abstract because they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Assessment of the included article quality

The assessment of the quality of the included articles was made by two authors (A.B. and I.A.) using a modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies [11]. The evaluation considered three factors: patient’s selection, comparability and the completeness of the reported results (postoperative outcomes). According to the NOS, when 3 or 4 points are attributed to patient’s selection and 1 or 2 points are attributed to comparability and 2 or 3 points are attributed to outcomes, the article is considered of “Good” quality. When 2 points are attributed to patient’s selection and 1 or 2 points are attributed to comparability and 2 or 3 points are attributed to outcomes, the article is considered of “Fair” quality. Finally, when 0 or 1 point is attributed to patient’s selection or 0 points are attributed to comparability or 0 points are attributed to outcomes, the article is considered of “Poor” quality [11]. For each article, the maximum score is nine points [11].

Assessment of risk of bias of the included articles

The assessment of risk of bias of the included articles was made by two authors (A.B. and I.A.) using the risk of bias in nonrandomised studies—of interventions (ROBIN-I) tool [12]. The evaluation considered seven domains: the first two domains cover confounding and selection of participants into the study, the third domain addresses classification of the interventions and the other four domains address biases due to deviations from intended interventions, missing data, outcomes measurement, and selection of the reported result [12]. For each domain, a judgment is assigned: low risk of bias (the study is comparable to a randomised trial); moderate risk of bias (the study provides sound evidence for a nonrandomised study but cannot be considered comparable to a randomised trial); serious risk of bias (the study has important problems); critical risk of bias (the study is too problematic to provide any useful evidence); no information on which to base a judgement about risk of bias. Finally, the same judgments are assigned at the entire article [12].

Study design

Data extracted from each article were: number of patients, age, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities and therapy that can influence the postoperative results, hernia area, mesh placement and site, concomitant surgical procedures, conversion, intra and 30-day postoperative complications, operative time, postoperative hospital stay, 30-day mortality, follow-up and recurrence.

After screening the titles and abstracts, we identified articles that fulfilled the eligibility criteria and reviewed their full text. Data were extracted by two surgeons (A.B. and I.A.) and stored in the Microsoft Excel program (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA).

Included articles were divided in three groups based on the surgical technique employed: Group A, articles which report minimally invasive anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparotomy; Group B, articles which report minimally invasive anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparoscopic or robotic approach; Group C, articles which report minimally invasive posterior CST with TAR, including both being performed by laparoscopy or robotic.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to report the categorical variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to report the continuous variables. In the articles in which the continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range, mean and SD were calculated according to Hozo et al. [13]. The differences between groups were estimated using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni as post hoc test for continuous variables and the Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS software 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and p value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

One hundred and one articles were fully analysed, and 73 further articles were excluded (Fig. 1). Finally, 28 articles, published between February 2000 and February 2019, were included in the present systematic review [7, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] as shown in the Preferred PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) [10]. Tables 2 and 3 show the assessment of articles’ quality based on the NOS and the of risk of bias of the included articles based on the ROBIN-I.

Data regarding group A are reported in Tables 4 and 7 [7, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Concomitant procedures were: panniculectomy (19), enterocutaneous fistula repair (1), ileostomy reversal (1) and colonoscopy (1) (11.2%) [7, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Data regarding group B are reported in Tables 5 and 7 [18, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. One intraoperative complication (0.8%) was observed (enterotomy during adhesiolysis) [30]. In 33 cases, closure of the midline was performed robotically (27.5%) [29].

Data regarding group C are reported in Tables 6 and 7 [34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Five intraoperative complications (2.1%) were observed (4 enterotomies, 1 subcutaneous emphysema) and concomitant procedures were: 9 inguinal hernia repair and 11 unspecified procedures (8.4%) [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. In 223 cases, CST was performed robotically (94.5%) [34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Table 7 shows the differences between groups. Regarding demographic data statistically significant differences were not observed in terms of age, BMI and hernia area. Overall comorbidity rate was 57.6%, 73.3% and more than 100%, in patients who underwent anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparotomy, anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparoscopy and posterior CST-TAR, respectively. Statistically significant differences were observed at each comparison between groups (Table 7).

Regarding the intraoperative data, statistically significant differences were not observed in terms of intraoperative complications, conversion to open surgery and operative time. Twenty-two (11.2%) and 20 (8.4%) concomitant procedures were performed in patients who underwent anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparotomy and posterior CST-TAR, respectively, none in patients who underwent anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparoscopy (Table 7).

Regarding the postoperative outcomes, patients who underwent anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparotomy experienced the highest surgical complications rate (31.2%), length of hospital stay (8.1 ± 3.7 days) and recurrence rate (10.7%) in comparison with patients who underwent anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparoscopy (15.8%, 7.2 ± 2.1 days and 6.6%, respectively) and patients who underwent posterior CST-TAR (17.8%, 2.4 ± 1.4 days and 0.4%, respectively). Statistical analysis shows statistically significant differences comparing the group of patients who underwent anterior CST and closure of the abdominal midline by laparotomy with the other two groups (Table 7).

Discussion

This systematic review was conducted with the aim to compare the outcomes after minimally invasive anterior and posterior CST to provide which is the best surgical treatment for the treatment of large abdominal ventral hernia. Most of the included articles had small sample of patients and missing or very heterogeneous data, as reported by the study quality assessment and the assessment of the risk of bias of the included articles (Tables 2 and 3). Moreover, due to the lack of randomized control trials, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis. Anyway, in terms of postoperative morbidity, group A has the higher surgical complications rate, followed by group C and B, respectively, achieving the statistically significant differences with groups B and C. One limitation of these results could be considered the fact that in group A there is 11.2% of patients who underwent concomitant procedures, that could increase the risk of surgical complications (since wounds in some of these cases would be considered a grade III, following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surgical wound classification [41], which are associated to higher surgical site occurrences, and panniculectomy itself could also be associated to more surgical site occurrences). Moreover, the concomitant procedures could be a limitation to perform a pure minimally invasive anterior CST or a posterior CST-TAR. In group C the type of concomitant procedures is not specified, and this is a limit for a good analysis of the results.

The recurrence rate is highest in group A, followed by group B and C, respectively, achieving the statistically significant differences with both groups B and C. Group C has the highest reported hernia area defect without, however, statistically significance difference and the lowest hospital stay and recurrence rate in comparison with other groups.

To note that most of posterior CST-TAR procedures (94.5%) were performed robotically, that could be a factor that lengthens the operating time.

CST is an effective and safe technique, and it quickly gained popularity for the treatment of the large abdominal defects [1]. It provides functional restoration of the muscles of the abdominal wall, without tension, and affords dynamic support to counter fluctuations of the intra-abdominal pressures [42]. If on one hand the introduction of minimally invasive surgery resulted in similar outcomes in terms of abdominal wall restoration in comparison to open CST, on the other hand it improves the outcomes in terms of morbidity rate and reduces the hospital stay in most of the previously reported articles [1, 2, 4, 5, 35]. In this sense, it has already been reported that a higher surgical postoperative complication rate, together with higher recurrence rate, are more common after open surgery in comparison to minimally invasive approach, so the use of this last one should be preferred to obtain less both early and late postoperative complications [43].

Even if CST provides a tension free reconstruction, the mesh placement during CST seems to provide better results if compared to primary closure [44,45,46,47]. Denney et al. reported a 13% of recurrence rate in patients who underwent CST and mesh placement [44]. Rezavi et al. showed recurrence rates of 14.8% and 34.6% in case of mesh placement or not after CST, respectively, confirming this data [45]. In the present review, all included articles reported the use of mesh, showing low recurrence rate [7, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. However, in the literature it is still debated which is the best prosthetic material to use in each case and the most proper anatomical plane to place the mesh [44,45,46,47], being evident in the present study a lack of a standardization of the procedures.

Despite previous published papers in the literature well documented the advantages of minimally invasive approach over the open one for the CST [1, 2, 4, 5, 9], a comparison which includes only patients treated with different minimally invasive CST is still missing. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review reported in the literature concerning the outcomes after different minimally invasive CST. The major limitations of the present study are the small sample of patients for each group, the heterogeneity of data reported in each article, which makes a comparison difficult, and the poor quality of the included papers. Moreover, the indications for surgery are not standardized in the included articles, being this another bias that can influence the results. Finally, it is difficult to achieve reliable data regarding recurrence due to the short follow-up reported in each group, especially in case of posterior CST-TAR. The mentioned above limitations affect the statistical analysis, being impossible a meta-analysis, and make difficult to draw firm conclusions.

In conclusion, based on the present study, anterior CST with closure of the abdominal midline by open approach showed the worst results in comparison with the other techniques, and therefore, it should be considered a hybrid technique, because patients do not benefit from the advantages of a pure minimally invasive approach. Minimally invasive posterior CST showed lower hospital stay and recurrence rate in comparison with the anterior CST, even if with the shorter follow-up period. Further prospective studies and randomized control trials, with wider sample size and longer follow-up are required to demonstrate which is the best surgical option in case of large ventral hernia.

References

Switzer NJ, Dykstra MA, Gill RS, Lim S, Lester E, de Gara C, Shi X, Birch DW, Karmali S (2015) Endoscopic versus open component separation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 29(4):787–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3741-1

Hodgkinson JD, Leo CA, Maeda Y, Bassett P, Oke SM, Vaizey CJ, Warusavitarne J (2018) A meta-analysis comparing open anterior component separation with posterior component separation and transversus abdominis release in the repair of midline ventral hernias. Hernia 22(4):617–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1757-5

Ramirez OM, Ruas E, Dellon AL (1990) “Components separation” method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg 86(3):519–526

Feretis M, Orchard P (2015) Minimally invasive component separation techniques in complex ventral abdominal hernia repair: a systematic review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 25(2):100–105. https://doi.org/10.1097/sle.0000000000000114

Tong WM, Hope W, Overby DW, Hultman CS (2011) Comparison of outcome after mesh-only repair, laparoscopic component separation, and open component separation. Ann Plast Surg 66(5):551–556. https://doi.org/10.1097/sap.0b013e31820b3c91

Joels CS, Vanderveer AS, Newcomb WL, Lincourt AE, Polhill JL, Jacobs DG, Sing RF, Heniford BT (2006) Abdominal wall reconstruction after temporary abdominal closure: a ten-year review. Surg Innov 13(4):223–230

Lowe JB, Garza JR, Bowman JL, Rohrich RJ, Strodel WE (2000) Endoscopically assisted “components separation” for closure of abdominal wall defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 105(2):720–729 quiz 730

Novitsky YW, Elliott HL, Orenstein SB, Rosen MJ (2012) Transversus abdominis muscle release: a novel approach to posterior component separation during complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Am J Surg 204(5):709–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.02.008

Winder JS, Lyn-Sue J, Kunselman AR, Pauli EM (2017) Differences in midline fascial forces exist following laparoscopic and open transversus abdominis release in a porcine model. Surg Endosc 31(2):829–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5040-5

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8(5):336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M (2014) Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-45

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I (2005) Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 5:13

Rosen MJ, Jin J, McGee MF, Williams C, Marks J, Ponsky JL (2007) Laparoscopic component separation in the single-stage treatment of infected abdominal wall prosthetic removal. Hernia 11(5):435–440

Bachman SL, Ramaswamy A, Ramshaw BJ (2009) Early results of midline hernia repair using a minimally invasive component separation technique. Am Surg 75(7):572–577 (discussion 577–578)

Cox TC, Pearl JP, Ritter EM (2010) Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair combined with laparoscopic separation of abdominal wall components: a novel approach to complex abdominal wall closure. Hernia 14(6):561–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-010-0704-x

Albright E, Diaz D, Davenport D, Roth JS (2011) The component separation technique for hernia repair: a comparison of open and endoscopic techniques. Am Surg 77(7):839–843

Azoury SC, Dhanasopon AP, Hui X, Tuffaha SH, De La Cruz C, Liao C, Lovins M, Nguyen HT (2014) Endoscopic component separation for laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repair: a single institutional comparison of outcomes and review of the technique. Hernia 18(5):637–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-014-1274-0

Ng N, Wampler M, Palladino H, Agullo F, Davis BR (2015) Outcomes of laparoscopic versus open fascial component separation for complex ventral hernia repair. Am Surg 81(7):714–719

Mommers EH, Wegdam JA, Nienhuijs SW, de Vries Reilingh TS (2016) How to perform the endoscopically assisted components separation technique (ECST) for large ventral hernia repair. Hernia 20(3):441–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-016-1485-7

Thomsen CØ, Brøndum TL, Jørgensen LN (2016) Quality of life after ventral hernia repair with endoscopic component separation technique. Scand J Surg 105(1):11–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496915571402

Dauser B, Ghaffari S, Ng C, Schmid T, Köhler G, Herbst F (2017) Endoscopic anterior component separation: a novel technical approach. Hernia 21(6):951–955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1671-2

Muse TO, Zwischenberger BA, Miller MT, Borman DA, Davenport DL, Roth JS (2018) Outcomes after ventral hernia repair using the rives-stoppa, endoscopic, and open component separation techniques. Am Surg 84(3):433–437

Köhler G, Fischer I, Kaltenböck R, Lechner M, Dauser B, Jorgensen LN (2018) Evolution of endoscopic anterior component separation to a precostal access with a new cylindrical balloon trocar. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 28(6):730–735. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2017.0480

Malik K, Bowers SP, Smith CD, Asbun H, Preissler S (2009) A case series of laparoscopic components separation and rectus medialization with laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 19(5):607–610. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2009.0155

Giurgius M, Bendure L, Davenport DL, Roth JS (2012) The endoscopic component separation technique for hernia repair results in reduced morbidity compared to the open component separation technique. Hernia 16(1):47–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0866-1

Moazzez A, Mason RJ, Darehzereshki A, Katkhouda N (2013) Totally laparoscopic abdominal wall reconstruction: lessons learned and results of a short-term follow-up. Hernia 17(5):633–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-013-1145-0

Fox M, Cannon RM, Egger M, Spate K, Kehdy FJ (2013) Laparoscopic component separation reduces postoperative wound complications but does not alter recurrence rates in complex hernia repairs. Am J Surg 206(6):869–874 (discussion 874–875). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.005

Oviedo RJ, Robertson JC, Desai AS (2017) Robotic ventral hernia repair and endoscopic component separation: outcomes. JSLS. https://doi.org/10.4293/jsls.2017.00055

Wiessner R, Vorwerk T, Tolla-Jensen C, Gehring A (2017) Continuous laparoscopic closure of the linea alba with barbed sutures combined with laparoscopic mesh implantation (IPOM plus repair) as a new technique for treatment of abdominal hernias. Front Surg 4:62. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2017.00062

Elstner KE, Read JW, Jacombs ASW, Martins RT, Arduini F, Cosman PH, Rodriguez-Acevedo O, Dardano AN, Karatassas A, Ibrahim N (2018) Single port component separation: endoscopic external oblique release for complex ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc 32(5):2474–2479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5949-3

Belyansky I, Zahiri HR, Park A (2016) Laparoscopic transversus abdominis release, a Novel minimally invasive approach to complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Surg Innov 23(2):134–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1553350615618290

Moore AM, Anderson LN, Chen DC (2016) Laparoscopic stapled sublay repair with self-gripping mesh: a simplified technique for minimally invasive extraperitoneal ventral hernia repair. Surg Technol Int 29:131–139

Amaral MVFD, Guimarães JR, Volpe P, Oliveira FMM, Domene CE, Roll S, Cavazzola LT (2017) Robotic transversus abdominis release (TAR): is it possible to offer minimally invasive surgery for abdominal wall complex defects? Rev Col Bras Circ 44(2):216–219. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-69912017002009

Bittner JG 4th, Alrefai S, Vy M, Mabe M, Del Prado PAR, Clingempeel NL (2018) Comparative analysis of open and robotic transversus abdominis release for ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc 32(2):727–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5729-0

Martin-Del-Campo LA, Weltz AS, Belyansky I, Novitsky YW (2018) Comparative analysis of perioperative outcomes of robotic versus open transversus abdominis release. Surg Endosc 32(2):840–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5752-1

Halka JT, Vasyluk A, DeMare AM, Janczyk RJ, Iacco AA (2018) Robotic and hybrid robotic transversus abdominis release may be performed with low length of stay and wound morbidity. Am J Surg 215(3):462–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.10.053

Belyansky I, Reza Zahiri H, Sanford Z, Weltz AS, Park A (2018) Early operative outcomes of endoscopic (eTEP access) robotic-assisted retromuscular abdominal wall hernia repair. Hernia 22(5):837–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1795-z

Halpern DK, Howell RS, Boinpally H, Magadan-Alvarez C, Petrone P, Brathwaite CEM (2019) Ascending the learning curve of robotic abdominal wall reconstruction. JSLS. https://doi.org/10.4293/jsls.2018.00084

Gokcal F, Morrison S, Kudsi OY (2019) Robotic retromuscular ventral hernia repair and transversus abdominis release: short-term outcomes and risk factors associated with perioperative complications. Hernia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-01911-1

Onyekwelu I, Yakkanti R, Protzer L, Pinkston CM, Tucker C, Seligson D (2017) Surgical wound classification and surgical site infections in the orthopaedic patient. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 1(3):e022. https://doi.org/10.5435/jaaosglobal-d-17-00022

Harth KC, Rosen MJ (2010) Endoscopic versus open component separation in complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Am J Surg 199(3):342–346 (discussion 346–347). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.015

Kurmann A, Visth E, Candinas D, Beldi G (2011) Long-term follow-up of open and laparoscopic repair of large incisional hernias. World J Surg 35(2):297–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0874-9

Denney B, de la Torre JI (2017) Multipoint suture fixation technique for abdominal wall reconstruction with component separation and onlay biological mesh placement. Am Surg 83(5):515–521

Razavi SA, Desai KA, Hart AM, Thompson PW, Losken A (2018) The impact of mesh reinforcement with components separation for abdominal wall reconstruction. Am Surg 84(6):959–962

Cornette B, De Bacquer D, Berrevoet F (2018) Component separation technique for giant incisional hernia: a systematic review. Am J Surg 215(4):719–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.07.032

Krpata DM, Blatnik JA, Novitsky YW, Rosen MJ (2012) Posterior and open anterior components separations: a comparative analysis. Am J Surg 203(3):318–322 (discussion 322). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.10.009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Dr. Andrea Balla, Dr. Isaias Alarcón and Prof. Salvador Morales-Conde declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balla, A., Alarcón, I. & Morales-Conde, S. Minimally invasive component separation technique for large ventral hernia: which is the best choice? A systematic literature review. Surg Endosc 34, 14–30 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07156-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07156-4