Abstract

Background

The component separation technique (CST) was developed to improve the integrity of abdominal wall reconstruction for large, complex hernias. Open CST necessitates large subcutaneous skin flaps and, therefore, is associated with significant ischemic wound complications. The minimally invasive or endoscopic component separation technique (MICST) has been suggested in preliminary studies to reduce wound complication rates post-operatively. In this study, we systematically reviewed the literature comparing open versus endoscopic component separation and performed a meta-analysis of controlled studies.

Methods

A comprehensive search of electronic databases was completed. All English, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized comparison study, and case series were included. All comparison studies included in the meta-analysis were assessed independently by two reviewers for methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tools.

Results

63 primary studies (3,055 patients) were identified; 7 controlled studies and 56 case series. The total wound complication rate was lower for MICST (20.6 %) compared to Open CST (34.6 %). MICST compared to open CST was shown to have lower rates of superficial infections (3.5 vs 8.9 %), skin dehiscence (5.3 vs 8.2 %), necrosis (2.1 vs 6.8 %), hematoma/seroma formation (4.6 vs 7.4 %), fistula tract formation (0.4 vs 1.0 %), fascial dehiscence (0.0 vs 0.4 %), and mortality (0.4 vs 0.6 %.) The open component CST did have lower rates of intra-abdominal abscess formation (3.8 vs 4.6 %) and recurrence rates (11.1 vs 15.1 %). The meta-analysis included 7 non-randomized controlled studies (387 patients). A similar suggestive overall trend was found favoring MICST, although most types of wound complications did not show to significance. MICST was associated with a significantly decreased rate of fascial dehiscence and was shown to be significantly shorter procedure.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis comparing MICST to open CST suggests MICST is associated with decreased overall post-operative wound complication rates. Further prospective studies are needed to verify these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Incisional hernias are a common post-operative complication, with an incidence of 5–15 % following open abdominal procedures and 1–3 % following minimally invasive abdominal procedures [1]. Large abdominal wall defects pose a challenging problem to correct for general surgeons. The options for closing these complicated defects, including primary repair, mesh, and distant muscle flaps, have yielded suboptimal results, therefore, in 1990, Ramirez et al. [2] first developed the component separation technique (CST) to address this issue. CST is based on the concept of re-establishing a functional abdominal wall with an autologous tissue repair. The procedure involves dividing the relatively fixed external oblique aponeurosis, elevating the rectus abdominus muscle from its posterior rectus sheath, and then mobilizing the myofascial flap consisting of the rectus, internal oblique, and transverse abdominus medially [2]. Allowing for approximately 10 cm of mobilization on each side, this procedure allows for a tension-free midline fascial closure [2]. CST avoids the absolute use of prosthetic material, which can be beneficial in contaminated fields [3].

Unfortunately, CST is not without its own procedural morbidity. The extensive lateral dissection required to create large subcutaneous skin flaps leads to marked wound complications [3]. Specifically, ligating a significant proportion of the perforating abdominal wall blood vessels predisposes the flap to ischemia and infection, in addition to potential formation of hematomas and seromas in the dead space [3, 4]. Wound infections rates have been shown to range from 25 to 57 % [4–7].

Minimally invasive component separation technique (MICST) was developed in efforts to address wound complications associated with necrosis. Introduced as a modification to the classic CST, usually coined endoscopic component separation (ECST), this new technique preserves the perforating abdominal wall vessels [3, 8]. Bilateral incisions are made at the medial insertion of the external oblique aponeurosis to the rectus sheath, an endoscopic balloon insufflator then separates the avascular plane between the external oblique and the internal oblique, and the external oblique is transected from pubic symphysis to costal margin using an endoscope. ECST has been suggested in preliminary studies to reduce wound complication rates post-operatively [4, 5]. To date, there has not been a systematic review and subsequent meta-analysis to critically assess the effectiveness of endoscopic compared to the classic open component separation. In this study, we systematically reviewed the literature comparing open versus minimally invasive component separation and performed a meta-analysis of controlled studies.

Methods

A comprehensive search of electronic databases (e.g., MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCOPUS, Web of science, and the Cochrane Library) using search terms “component separation” was completed. All randomized controlled trials, non-randomized comparison study, and case series were included. All human studies limited to English were included. Two independent reviewers screened abstracts, reviewed full text versions of all studies, classified and extracted data. All comparison studies included in the meta-analysis were assessed independently by two reviewers for methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tools. Disagreements were resolved by re-extraction, or third party adjudication. Where possible and appropriate, a meta-analysis was conducted.

Assessment of study eligibility

We systematically reviewed each study according to the following criteria: (1) There were no study format restrictions for the systematic review, but the meta-analysis contained only controlled studies; (2) Involved either open or minimally invasive component separation or both; (3) The study report at least one of the desired wound complication outcome mentioned below; (4) Enrolled at least 5 patients; (5) Studies that involved significant variations in the open or minimally invasive technique, as determined by the two reviewers or third party adjudicators were also excluded.

Outcomes of interest

The primary outcomes of interest were wound complications: superficial wound infection, skin dehiscence, necrosis requiring debridement, hematoma or seroma formation, abscess formation, fascial dehiscence, and fistula formation. Secondary outcomes included mortality, recurrence rates of hernia re-operation rate for hernia rates, age, sex, BMI, operating room time, number of previous surgeries, number of previous incisional hernia repairs, length of stay in hospital, defect size, the use of reinforcing mesh, the type of mesh (biologic or synthetic), and follow-up time.

Results

Search results

A total of 722 studies were identified using our search criteria for screening (Fig. 1). After an assessment according to our exclusion criteria, 402 were excluded based on abstract alone and not meeting the basic requirement of data on open or minimally invasive component separation. Of 320 remained for review, 257 were excluded based on insufficient primary outcomes, enrollment of less than 5 patients, and results published in another included trial. Thus, a total of 63 primary studies (3,055 patients) were identified that met our inclusion criteria for the systematic review and were assessed by full manuscript. These included no randomized controlled trials, 7 controlled studies [5–11], and 56 case series [3, 12–64].

Included studies: systematic review

All 63 included studies reported wound complication outcome data following endoscopic and/or open component separation. The baseline patient characteristics and wound complication data in the included studies are listed in Table 1. A total of 3,055 patients were assessed and number of patients ranged from 5 to 545. The average age in the MIS and Open groups were 57.8 years and 55.7 years, respectively; with 55 and 52 % of the patients were male, respectively. The patients had a mean follow-up time of 15.5 months (MIS) and 25.8 months (Open).

The primary outcome was wound complication following MIS versus Open CST (Table 1). The total wound complication rate was lower for ECST (20.6 %) compared to Open CST (34.6 %). MICST compared to open CST was shown to have lower mean rates of superficial wound infections (3.5 vs 8.9 %), skin dehiscence (5.3 vs 8.2 %), necrosis/debridement (2.1 vs 6.8 %), hematoma/seroma formation (4.6 vs 7.4 %), fistula tract formation (0.4 vs 1.0 %), fascial dehiscence (0.0 vs 0.4 %), and mortality (0.4 vs 0.6 %). The open component CST did have lower rates of intra-abdominal abscess formation (3.8 vs 4.6 %) and recurrence rates (11.1 vs 15.1 %).

Secondary outcomes included mortality, recurrence of hernias, and reoperation rate for hernia. Mortality rates were lower with MICST (0.4 vs 0.6 %), while recurrence (15.0 vs 11.1 %) and reoperation (4.7 vs 2.6 %) favored the open technique.

Included studies: meta-analysis

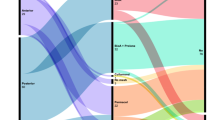

The meta-analysis included 7 non-randomized controlled studies (387 patients). The basic demographic data as well as wound complication data are shown in Table 2. A similar overall trend was found that suggests Minimally Invasive CST has decreased wound infection rates, although most types of wound complications did not show to significance. MICST was associated with a significantly decreased rate of fascial dehiscence (odds ratio = 3.18, p = 0.02) and was shown to be significantly shorter procedure (p = 0.02). Forest plots were constructed of wound complication data (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

Discussion

Component separation repair of abdominal wall hernias allows for restoration of a functional, muscular abdominal wall that can provide dynamic support to counter fluctuations in intra-abdominal pressures [7]. It is quickly becoming a safe and effective approach to closing larger abdominal defects, especially in previously infected fields. De Vries Reilingh et al. [33] published the results of a randomized controlled trial comparing mesh prosthetic repairs versus the CST for giant abdominal wall defects, the results favored the use of CST over mesh repair due to the frequency of mesh infections.

However, the advantages of the classic CST over other possible hernia repair techniques are mitigated with the high prevalence of wound infections as shown in single institution studies controlled studies [4–7] Therefore, MICST was introduced to improve on this deficiency of the classical technique [3, 8]. From the few controlled trials comparing the techniques and the limited number of patients enrolled in those studies, it appears that wound infections are decreased using the endoscopic approach. Our systematic review and meta-analysis is the first paper to systematically review the literature to formally compare the two techniques.

The systematic review showed that wound complications were almost halved in the minimally invasive group, with 20 % of patients suffering a wound complication following endoscopic intervention compared to 34 % in open. With the exception of abscess formation and recurrence of hernia, all other wound complications were decreased with MICST compared to the classical technique. While the meta-analysis did not find a significant difference with the exception of a decreased rate of skin dehiscence, it appears that most wound complications tend to trend toward favoring the minimally invasive procedure. We suspect that with an increase in the number of primary studies, this trend will reach significance. This lack of apparent significance is most likely related to the lack of sufficient primary studies, only 7 studies meeting our inclusion criteria, with an adequate amount of enrolled patients, with less than 400 patients included. In addition, there remains a paucity in the literature for randomized controlled trials comparing the two techniques.

Avoiding large myofascial skin flaps, in the minimally invasive approach, that widely ligate the abdominal wall perforators leads to adequate tissue blood supply, improved cellular function, resistance to infection, and tissue healing [60]. Studies have shown that tissue hypoxia cause by disrupted vasculature leads to increased wound infection rates, this is explained on a cellular level as oxygen is converted to cellular messengers called reactive oxygen species which promote processes that support wound healing including cytokine action, angiogenesis, cell motility, and extracellular matrix formation [65].

The trend for an increase in hernia recurrence with the endoscopic approach could be explained be a few factors. First off, only 47 % of MICST patients received mesh placement compared to 62 % of patients following open component, leading to the possibility of decreased rectus reinforcement and increased hernia occurrence. In addition, MICST might be substituting one ventral hernia for another one, as the site of the lateral release of the external oblique has the potential for creating abdominal wall weakness [5]. Unlike in the open technique, where the operator has the ability to reinforce the potential defect with mesh, such is a drawback of the endoscopic approach. Clarke et al. [5] reported 22 % of recurrences in the perforator preserving group were due to hernias at the lateral release point.

In addition to avoiding large potentially hypoxic tissue flaps, another theoretical advantage of MICST, proposed by Rosen et al., is that the lateral tunnels provide a clean space away from the midline wound in the event of a previously infected or contaminant centralized abdominal field and might decrease the complexity of any subsequent wound infection, in the event that they do develop [23].

In the patient population with previous ostomy sites, there is considerable debate to whether the MICST is advantageous or not. Theoretically, MICST avoids dissection over the scarred anterior rectus sheath that is required in creating large tissue flaps [6]. However, scarring from lateral ostomies and previous lateral incisions would make performing lateral tunnels extremely challenging [12]. Nevertheless, Ghali et al. [6] argue that MICST is actually valuable in general in cases, where the rectus sheath has encountered scarring from previous incisions and ostomies, as it avoids the dissection over the anterior sheath to create large tissue flaps. Therefore, it seems that previous midline incisions and ostomies favor MICST, while old ostomy sites and incisions more laterally favor open.

An important disadvantages of the MICST are that studies have shown that endoscopic techniques are not able to achieve the amount of midline mobilization compared to open, as endoscopic techniques only have a reported 86 % of the release in comparison to open [12]. This could limit their utility in the larger, giant hernias.

Since its introduction by Ramirez et al. [2], there have been slight modifications to the classical, open technique. One of the enhancements of the classic technique is mesh reinforcement of the midline abdominal wound. Reinforcing mesh can be placed either anterior to the rectus fascia or in the recto-rectus space (underlay versus onlay) based mostly on surgeon preference [6, 9]. Another point of potential diversion is whether or not to divide the posterior rectus sheath as originally described. In our meta-analysis study, 86 % of authors in the meta-analysis dissected through the posterior rectus in order to gain over 3 cm of mobilization per side [12]. Other diversions include “the open book” technique, using the mobile rectus sheath as a turn-over flap to reinforce the rectus abdominal muscle in the midline and the preservation the periumbilical perforating vessels technique [59, 60].

Slight modifications also exist in the minimally invasive techniques included in this review. The original operative technique described by Lowe et al. [8] and Maas et al. [3, 8] used balloon insufflation to expose the avascular plane and a video-endoscope to release the external oblique muscle. Other minimally invasive techniques include developing the avascular plane with Yankauer suction and dissecting with hand held electrocautery [6]. Combining ECST with laparoscopic incisional hernia repair is also becoming increasingly popular [55].

In general, suitable patient selection is crucial in deciding whether to perform a component separation in the first place. Elderly, sedentary patients would not benefit as much as a younger, active patient from a functional abdominal wall and might not handle a larger surgery as well [5].

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis comparing MICST to open CST suggests MICST is associated with decreased overall post-operative wound complication rates including superficial infections, hematoma/seroma formation, necrosis, fistula formation, and both skin and fascial dehiscence. However, further prospective studies are needed to verify these findings to significance.

References

Dholakia C, Reavis KM (2010) Component separation in the treatment of incisional hernias. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 20:129–132

Ramirez OM, Ruas E, Dellon AL (1990) “Components separation” method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg 86:519–526

Maas SM, de Vries RS, van Goor H, de Jong D, Bleichrodt RP (2002) Endoscopically assisted “components separation technique” for the repair of complicated ventral hernias. J Am Coll Surg 194:388–390

Albright E, Diaz D, Davenport D, Roth JS (2011) The component separation technique for hernia repair: a comparison of open and endoscopic techniques. Am Surg 77:839–843

Clarke JM (2010) Incisional hernia repair by fascial component separation: results in 128 cases and evolution of technique. Am J Surg 200:2–8

Ghali S, Turza KC, Baumann DP, Butler CE (2012) Minimally invasive component separation results in fewer wound-healing complications than open component separation for large ventral hernia repairs. J Am Coll Surg 214:981–989

Harth KC, Rosen MJ (2010) Endoscopic versus open component separation in complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Am J Surg 199:342–346 discussion 346–347

Lowe JB, Garza JR, Bowman JL, Rohrich RJ, Strodel WE (2000) Endoscopically assisted “components separation” for closure of abdominal wall defects. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 105:720–729 quiz 730

Giurgius M, Bendure L, Davenport DL, Roth JS (2012) The endoscopic component separation technique for hernia repair results in reduced morbidity compared to the open component separation technique. Hernia 16:47–51

Lipman J, Medalie D, Rosen MJ (2008) Staged repair of massive incisional hernias with loss of abdominal domain: a novel approach. Am J Surg 195:84–88

Parker M, Bray JM, Pfluke JM, Asbun HJ, Smith CD, Bowers SP (2011) Preliminary experience and development of an algorithm for the optimal use of the laparoscopic component separation technique for myofascial advancement during ventral incisional hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 21:405–410

Bachman SL, Ramaswamy A, Ramshaw BJ (2009) Early results of midline hernia repair using a minimally invasive component separation technique. Am Surg 75:572–577 discussion 577–578

Bogetti P, Boriani F, Gravante G, Milanese A, Ferrando PM, Baglioni E (2012) A retrospective study on mesh repair alone vs. mesh repair plus pedicle flap for large incisional hernias. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 16:1847–1852

Dragu A, Klein P, Unglaub F, Polykandriotis E, Kneser U, Hohenberger W, Horch RE (2009) Tensiometry as a decision tool for abdominal wall reconstruction with component separation. World J Surg 33:1174–1180

Ekeh AP, McCarthy MC, Woods RJ, Walusimbi M, Saxe JM, Patterson LA (2006) Delayed closure of ventral abdominal hernias after severe trauma. Am J Surg 191:391–395

Garvey PB, Bailey CM, Baumann DP, Liu J, Butler CE (2012) Violation of the rectus complex is not a contraindication to component separation for abdominal wall reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg 214:131–139

Hood K, Millikan K, Pittman T, Zelhart M, Secemsky B, Rajan M, Myers J, Luu M (2013) Abdominal wall reconstruction: a case series of ventral hernia repair using the component separation technique with biologic mesh. Am J Surg 205:322–327 discussion 327–328

Li EN, Silverman RP, Goldberg NH (2005) Incisional hernia repair in renal transplantation patients. Hernia 9:231–237

Mazzocchi M, Dessy LA, Ranno R, Carlesimo B, Rubino C (2011) “Component separation” technique and panniculectomy for repair of incisional hernia. Am J Surg 201:776–783

Vargo D (2004) Component separation in the management of the difficult abdominal wall. Am J Surg 188:633–637

Satterwhite TS, Miri S, Chung C, Spain DA, Lorenz HP, Lee GK (2012) Abdominal wall reconstruction with dual layer cross-linked porcine dermal xenograft: the “Pork Sandwich” herniorraphy. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg 65:333–341

Sailes FC, Walls J, Guelig D, Mirzabeigi M, Long WD, Crawford A, Moore JH Jr, Copit SE, Tuma GA, Fox J (2010) Synthetic and biological mesh in component separation: a 10-year single institution review. Ann Plast Surg 64:696–698

Rosen MJ, Jin J, McGee MF, Williams C, Marks J, Ponsky JL (2007) Laparoscopic component separation in the single-stage treatment of infected abdominal wall prosthetic removal. Hernia 11:435–440

Butler CE, Campbell KT (2011) Minimally invasive component separation with inlay bioprosthetic mesh (MICSIB) for complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 128:698–709

Moore M, Bax T, MacFarlane M, McNevin MS (2008) Outcomes of the fascial component separation technique with synthetic mesh reinforcement for repair of complex ventral incisional hernias in the morbidly obese. Am J Surg 195:575–579 discussion 579

Nasajpour H, LeBlanc KA, Steele MH (2011) Complex hernia repair using component separation technique paired with intraperitoneal acellular porcine dermis and synthetic mesh overlay. Ann Plast Surg 66:280–284

Agnew SP, Small W Jr, Wang E, Smith LJ, Hadad I, Dumanian GA (2010) Prospective measurements of intra-abdominal volume and pulmonary function after repair of massive ventral hernias with the components separation technique. Ann Surg 251:981–988

Yegiyants S, Tam M, Lee DJ, Abbas MA (2012) Outcome of components separation for contaminated complex abdominal wall defects. Hernia 16:41–45

Wind J, van Koperen PJ, Slors JF, Bemelman WA (2009) Single-stage closure of enterocutaneous fistula and stomas in the presence of large abdominal wall defects using the components separation technique. Am J Surg 197:24–29

Broker M, Verdaasdonk E, Karsten T (2011) Components separation technique combined with a double-mesh repair for large midline incisional hernia repair. World J Surg 35:2399–2402

Carbonell AM, Cobb WS, Chen SM (2008) Posterior components separation during retromuscular hernia repair. Hernia 12:359–362

de Vries Reilingh TS, van Goor H, Rosman C, Bemelmans MH, de Jong D, van Nieuwenhoven EJ, van Engeland MI, Bleichrodt RP (2003) “Components separation technique” for the repair of large abdominal wall hernias. J Am Coll Surg 196:32–37

de Vries Reilingh TS, van Goor H, Charbon JA, Rosman C, Hesselink EJ, van der Wilt GJ, Bleichrodt RP (2007) Repair of giant midline abdominal wall hernias: “components separation technique” versus prosthetic repair: interim analysis of a randomized controlled trial. World J Surg 31:756–763

Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, Dominguez I, Zamora-Valdes D, Castillo T, Fernandez-Diaz OF, Luna-Torres HA (2013) Closure of midline contaminated and recurrent incisional hernias with components separation technique reinforced with plication of the rectus muscles. Hernia 17:75–79

Ewart CJ, Lankford AB, Gamboa MG (2003) Successful closure of abdominal wall hernias using the components separation technique. Ann Plast Surg 50:269–273; discussion 273–274

Gonzalez R, Rehnke RD, Ramaswamy A, Smith CD, Clarke JM, Ramshaw BJ (2005) Components separation technique and laparoscopic approach: a review of two evolving strategies for ventral hernia repair. The American surgeon 71:598–605

Jernigan TW, Fabian TC, Croce MA, Moore N, Pritchard FE, Minard G, Bee TK (2003) Staged management of giant abdominal wall defects: acute and long-term results. Ann Surg 238:349–355 discussion 355–357

Ko JH, Wang EC, Salvay DM, Paul BC, Dumanian GA (2009) Abdominal wall reconstruction: lessons learned from 200 “components separation” procedures. Arch Surg 144:1047–1055

Kolker AR, Brown DJ, Redstone JS, Scarpinato VM, Wallack MK (2005) Multilayer reconstruction of abdominal wall defects with acellular dermal allograft (AlloDerm) and component separation. Ann Plast Surg 55:36–41 discussion 41–42

Krpata DM, Blatnik JA, Novitsky YW, Rosen MJ (2012) Posterior and open anterior components separations: a comparative analysis. Am J Surg 203:318–322 discussion 322

Celdran-Uriarte A, Fraile M, Garcia-Vasquez C, York E, Manso B, Granizo JJ (2011) A simplified incision of the external oblique aponeurosis during the components separation technique for the repair of large incisional hernias. Am J Surg 202:e31–e33

Cox TC, Pearl JP, Ritter EM (2010) Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair combined with laparoscopic separation of abdominal wall components: a novel approach to complex abdominal wall closure. Hernia 14:561–567

Morris LM, LeBlanc KA (2013) Components separation technique utilizing an intraperitoneal biologic and an onlay lightweight polypropylene mesh: “a sandwich technique”. Hernia 17:45–51

Novitsky YW, Elliott HL, Orenstein SB, Rosen MJ (2012) Transversus abdominis muscle release: a novel approach to posterior component separation during complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Am J Surg 204:709–716

van Geffen HJ, Simmermacher RK, van Vroonhoven TJ, van der Werken C (2005) Surgical treatment of large contaminated abdominal wall defects. J Am Coll Surg 201:206–212

Shabatian H, Lee DJ, Abbas MA (2008) Components separation: a solution to complex abdominal wall defects. Am Surg 74:912–916

Patel KM, Nahabedian MY, Gatti M, Bhanot P (2012) Indications and outcomes following complex abdominal reconstruction with component separation combined with porcine acellular dermal matrix reinforcement. Ann Plast Surg 69:394–398

Baumann DP, Butler CE (2010) Component separation improves outcomes in VRAM flap donor sites with excessive fascial tension. Plast Reconstr Surg 126:1573–1580

Campbell CA, Butler CE (2011) Use of adjuvant techniques improves surgical outcomes of complex vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap reconstructions of pelvic cancer defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 128:447–458

Chang EI, Foster RD, Hansen SL, Jazayeri L, Patti MG (2007) Autologous tissue reconstruction of ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients. Arch Surg 142:746–749 discussion 749–751

Girotto JA, Chiaramonte M, Menon NG, Singh N, Silverman R, Tufaro AP, Nahabedian M, Goldberg NH, Manson PN (2003) Recalcitrant abdominal wall hernias: long-term superiority of autologous tissue repair. Plast Reconstr Surg 112:106–114

Hadeed JG, Walsh MD, Pappas TN, Pestana IA, Tyler DS, Levinson H, Mantyh C, Jacobs DO, Lagoo-Deenadalayan SA, Erdmann D (2011) Complex abdominal wall hernias: a new classification system and approach to management based on review of 133 consecutive patients. Ann Plast Surg 66:497–503

Kanaan Z, Hicks N, Weller C, Bilchuk N, Galandiuk S, Vahrenhold C, Yuan X, Rai S (2011) Abdominal wall component release is a sensible choice for patients requiring complicated closure of abdominal defects. Langenbeck’s archives of surgery/Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie 396:1263–1270

Lineaweaver W (2012) Improvement of success rates for abdominal component reconstructions using bovine fetal collagen. Ann Plast Surg 68:438–441

Moazzez A, Mason RJ, Darehzereshki A, Katkhouda N (2013) Totally laparoscopic abdominal wall reconstruction: lessons learned and results of a short-term follow-up. Hernia 17:633–638

Shestak KC, Edington HJ, Johnson RR (2000) The separation of anatomic components technique for the reconstruction of massive midline abdominal wall defects: anatomy, surgical technique, applications, and limitations revisited. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 105:731–738 quiz 739

Varkarakis G, Daniels J, Coker K, Oswald T, Schleich A, Muskett A, Akdemir O, Lineaweaver W (2010) Effects of comorbidities and implant reinforcement on outcomes after component reconstruction of the abdominal wall. Ann Plast Surg 64:595–597

Szczerba SR, Dumanian GA (2003) Definitive surgical treatment of infected or exposed ventral hernia mesh. Ann Surg 237:437–441

Mericli AF, Bell D, DeGeorge BR Jr, Drake DB (2013) The single fascial incision modification of the “open-book” component separation repair: a 15-year experience. Ann Plast Surg 71:203–208

Saulis AS, Dumanian GA (2002) Periumbilical rectus abdominis perforator preservation significantly reduces superficial wound complications in “separation of parts” hernia repairs. Plast Reconstr Surg 109:2275–2280 discussion 2281–2282

Picazo-Yeste J, Morandeira-Rivas A, Moreno-Sanz C (2013) Multilayer myofascial-mesh repair for giant midline incisional hernias: a novel advantageous combination of old and new techniques. J Gastrointest Surg 17:1665–1672

Borud LJ, Grunwaldt L, Janz B, Mun E, Slavin SA (2007) Components separation combined with abdominal wall plication for repair of large abdominal wall hernias following bariatric surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 119:1792–1798

Ennis LS, Young JS, Gampper TJ, Drake DB (2003) The “open-book” variation of component separation for repair of massive midline abdominal wall hernia. Am Surg 69:733–742 discussion 742–743

DiBello JN Jr, Moore JH Jr (1996) Sliding myofascial flap of the rectus abdominus muscles for the closure of recurrent ventral hernias. Plast Reconstr Surg 98:464–469

Gordillo GM, Sen CK (2003) Revisiting the essential role of oxygen in wound healing. Am J Surg 186:259–263

Disclosures

Noah J. Switzer: Nothing to disclose; Mark A. Dykstra: Nothing to disclose; Richdeep S. Gill: Nothing to disclose; Stephanie Lim: Nothing to disclose; Erica Lester: Nothing to disclose; Christopher de Gara: Nothing to disclose; Xinzhe Shi: Nothing to disclose; Daniel W. Birch: consultant for ethicon and covidien; Shahzeer Karmali: consultant for ethicon and covidien

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented at the SAGES 2014 Annual Meeting, April 2–5, 2014, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Switzer, N.J., Dykstra, M.A., Gill, R.S. et al. Endoscopic versus open component separation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 29, 787–795 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3741-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3741-1