Abstract

Background

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric cancer (EGC) is expected to provide better long-term health-related quality of life (HRQOL) by preserving the entire stomach. We aimed to compare serial changes in HRQOL characteristics between patients who underwent ESD versus surgery for EGC.

Methods

A gastric cancer patient cohort was prospectively enrolled from 2004 to 2007. HRQOL of 161 EGC patients was prospectively assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and the stomach cancer-specific module EORTC-QLQ-STO22 at baseline (i.e., diagnosis) and at 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of post-treatment.

Results

Of 161 patients, 48 (29.8%) underwent ESD and 113 (70.2%) underwent surgery. HRQOL parameters of ESD patients were similar to or better than baseline values. At 1-month post-treatment, the surgery group had significantly poorer scores than the ESD group (P < 0.05) for factors except emotional and cognitive functioning, financial problems, anxiety, and hair loss. However, most of the HRQOL parameters in the surgery group improved during the first post-treatment year, with between-group differences becoming insignificant. Only five parameters (physical functioning, eating restriction, dysphagia, diarrhea, and body image) remained significantly better in the ESD group than the surgery group for > 1-year post-treatment (P < 0.05). The surgery group had significantly higher treatment-associated complications than the ESD group (15.0 vs. 2.1%; P = 0.017). The overall survival was not different between the both groups (5-year overall survival rates, 97.7% in the ESD group vs. 99.1% in the surgery group; P = 0.106 by the log-rank test).

Conclusion

Compared with surgery, ESD can provide better HRQOL benefits for EGC patients, especially during the early post-treatment period. However, surgical treatment should not be rejected only due to the concern about HRQOL impairments because most of them improved during follow-up periods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Radical gastrectomy with lymph node dissection is a standard treatment for gastric cancer [1]. Because of the gastric resection and the subsequent reconstruction of the gastrointestinal tract, patients who undergo gastrectomy suffer from various impairments in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) characteristics in the areas of nutrition, function, and symptom problems [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, long-term cohort studies have revealed that this early post-surgery HRQOL impairment gradually improves and recovers by 6-month post-treatment [6,7,8,9,10].

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been widely performed as a curative treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC) lesions meeting treatment guideline indication criteria for endoscopic resection [1, 11]. Compared with surgery, patients who undergo ESD are expected to have better HRQOL outcomes because the entire stomach is preserved. A recent study of EGC patients found that compared with surgery, ESD provides better post-treatment HRQOL outcomes for body image and for most symptom scales [12]. However, this study used a cross-sectional design and did not evaluate the HRQOL scales, which can change during the long-term post-EGC treatment follow-up period.

Therefore, we used a prospective cohort study design to investigate whether intermediate-term post-ESD HRQOL characteristics were better than those after gastrectomy in EGC patients.

Methods

Patients and study design

We prospectively enrolled consecutive patients newly diagnosed with gastric cancer regardless of cancer stage in our gastric cancer cohort after completion of informed consent at the National Cancer Center, Korea from July 2004 to May 2007. Inclusion criteria for this cohort were (1) age > 18 years, (2) pathologically diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma, and (3) no other organ cancer. Among the enrolled patients in this cohort, only data from EGC patients (T1a or T1b regardless of lymph node metastasis) who underwent ESD or surgery with curative intent were included in the analyses of the present study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, Korea (IRB approval number, NCCNCS-04-035).

ESD and surgical procedures

Patients underwent the diagnostic evaluations including esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy and abdomen computed tomography. The choice of treatment modalities between ESD and surgery was decided after a thorough review of the diagnostic evaluations in a multi-disciplinary conference.

ESD was performed for EGC cases according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guideline for clinically absolute indication (i.e., mucosal lesion with differentiated-type adenocarcinoma without ulcerative findings and tumor size ≤ 2 cm) [1]. Cases that met absolute and expanded criteria for the pathologic evaluation of the resected specimen were considered to achieve curative resection. Detailed procedures for ESD and post-ESD management were described in a previous article [13].

Laparoscopic or open radical gastrectomy with lymph node dissection was performed for the patients who underwent surgery. A D1 + or more lymph node dissection was performed following treatment guidelines [1]. The Billroth I or II and Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy were the reconstruction methods used for subtotal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy, respectively.

Assessment of baseline and follow-up HRQOL characteristics

The patients who participated in this study were followed up during post-treatment outpatient clinic visits at 1 month and then every 6 months, until 24 months after EGC treatment. We used the validated Korean version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30-item core QOL questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C30) and the gastric cancer-specific module of the 22-item QOL questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-STO22) to evaluate post-treatment HRQOL changes [14,15,16]. A well-trained coordinator collected the data through direct contact with patients at baseline and at every follow-up visit.

The EORTC-QLQ-C30 consists of five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), a global health status, three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea/vomiting), five single items for common symptoms reported by cancer patients (dyspnea, appetite loss, sleep disturbance, constipation, and diarrhea), and question about perceived financial difficulties attributable to the disease and treatment [14, 15]. All scales were measured to a 0 to 100 linear score. Higher values represented better HRQOL for the functional scales and global health status. Lower values indicated better HRQOL for the symptom scales and financial difficulties.

The EORTC-QLQ-STO22 consists of a single functional item (body image), five symptom scales (dysphagia, eating restrictions, pain, reflux, and anxiety), and three single symptom items (dry mouth, taste disturbance, and hair loss) [16]. Lower values indicated a better HRQOL.

Statistical analysis

To compare baseline demographic characteristics between patients who were treated using ESD or surgery, the student t test for continuous variables and the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were performed. The inverse probability of response weighting approach was used to adjust for between-treatment differences [17]. For this approach, the data were further weighted according to the reciprocal of the propensity scores estimated from the logistic regression model by including demographic variables that showed significant differences according to treatment. After the weighting was performed, propensity score adjusted F-statistics based on the Wald Chi-square statistic was estimated for comparisons of baseline demographics. Tumor characteristics were also compared between the ESD and surgery groups. Overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed by the log-rank test. Analyses for serial HRQOL changes were performed using data weighted to the total number of included patients. To compare HRQOL changes during the 24-month post-treatment period, analyses using the multivariate generalized linear model controlled for age, sex, and propensity scores were performed at each follow-up visit. The completion rates of the HRQOL questionnaires were 78.3% at 1-month visit, 84.5% at 6-month visit, 90.1% at 12-month visit, 82.6% at 18-month visit, and 78.3% at 24-month visit; the completion rates after the ESD and surgery were not different at each follow-up visit. Missing data were handled using the multiple imputation approach. Within-treatment analyses comparing HRQOL changes between the baseline and each follow-up visit were performed using a generalized linear model after multiple imputation was used to handle missing data. The student t test was used for comparisons of serial HRQOL changes at each visit between treatment groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). P values < 0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant result.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

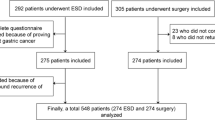

From July 2004 through May 2007, 48 patients who underwent ESD (ESD group) and 113 patients who underwent surgery (surgery group) were included in the study. Five patients who underwent additional surgery because of non-curative resection after ESD were included in the surgery group. The median age for all patients was 58 years (interquartile range, 49–66 years); 72.7% of the patients were male. The mean age of the ESD group patients was significantly higher, compared with the surgery group patients. The results for the weighting procedure indicated that the baseline characteristics were not different between the ESD and surgery groups, after propensity score adjustment was performed (Table 1).

The results for patient tumor characteristics and treatment are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The ESD group patients had smaller tumors, and greater proportions of lower-third tumor location and differentiated histologic type tumors. The final pathologic stage results indicated that the proportion of patients who had a T1b (tumor invading submucosa) lesion was significantly greater in the surgery group compared with the ESD group.

Treatment-associated complications occurred in one patient (2.1%) after ESD and in 17 patients (15.0%) after surgery. The surgery group had significantly higher rate of treatment-associated complications than the ESD group (P = 0.017). Early complications occurring within 30 days after the treatments were not different between the ESD and surgery groups. However, late complications occurred only in the surgery group, and 90% (9/10 patients) of the late complications were grade III or higher of the Clavien–Dindo classification (Table 2). The 5-year OS rates were 97.9% in the ESD group and 99.1% in the surgery group, and there was no significant difference (P = 0.106 by the log-rank test). There was no gastric cancer-related death during 5-year after treatments, and DSS was not different between the ESD and surgery groups.

Comparisons of HRQOL during the 24 months of follow-up

The comparisons of overall comprehensive HRQOL changes during 24-month post-treatment follow-up and those of HRQOL at each time point are presented in Figs. 1A–F and 2A–F.

Comparisons of mean changes in HRQOL scores (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30) between ESD and surgery groups; A Global health status, B Physical functioning, C Social functioning, D Pain, E Appetite loss, F Diarrhea. P overall was obtained from the analysis using the multivariate generalized linear model. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by the student t test between ESD and surgery groups at each time point. ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection, HRQOL health-related quality of life, M month

Comparisons of mean changes in HRQOL scores (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer STO22) between ESD and surgery groups; A dysphagia, B pain, C eating restrictions, D anxiety, E dry mouth, F body image. P overall was obtained from the analysis using the multivariate generalized linear model. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by the student t test between ESD and surgery groups at each time point. ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection, HRQOL health-related quality of life, M month

The EORTC-QLQ-C30 questionnaire assessment revealed that during the 24-month follow-up, the ESD group had significantly better functional scales for global health status (P overall = 0.012), social functioning (P overall = 0.007), pain (P overall = 0.001), and appetite loss (P overall = 0.025) compared with the surgery group. These items were significantly worse in the surgery group during the early post-treatment periods; however, the statistical significant differences became insignificant after 12 months. The scales of physical functioning (Fig. 1B) and diarrhea (Fig. 1F) were not different during the 24-month follow-up. However, physical functioning was significantly better after ESD than after surgery at each post-treatment visit throughout the 24-month follow-up (Fig. 1B). Diarrhea symptom scale that was not different at 1-month post-treatment (P = 0.058) became statistically significant at 6 months and later (P < 0.01; Fig. 1F).

The EORTC-QLQ-STO22 questionnaire analysis revealed that HRQOL for most of the symptom scales, including dysphagia (P overall < 0.001), pain (P overall < 0.001), eating restrictions (P overall < 0.001), anxiety (P overall = 0.015), dry mouth (P overall = 0.003), and body image (P overall = 0.017) were better for the ESD group than for the surgery group during 24-month post-treatment period. Of these, dysphagia (Fig. 2A) and eating restriction (Fig. 2C) were worse in the surgery group than in the ESD group until 18-month post-treatment. However, those differences were not present at the 24-month follow-up. Body image was consistently better in the ESD group than in the surgery group at each post-treatment follow-up period until 24 months (Fig. 2F).

The HRQOL comparisons for the remaining items between the both groups are presented in the Supplementary Table 2.

HRQOL at each follow-up visit compared with baseline

Compared with the baseline HRQOL, ESD group showed no impairment of HRQOL based on the both questionnaires at each post-treatment follow-up visit. In the surgery group, most impaired functional and symptom HRQOL scores symptom scales at 1-month follow-up visit were improved at the 6- or 12-month follow-up visit. However, symptom scales of fatigue and diarrhea (EORTC-QLQ-C30 questionnaire), dysphagia, eating restrictions, anxiety, and body image (EORTC-QLQ-STO22 questionnaire) were continuously impaired until 24-month follow-up visit compared with the baseline (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

This prospective cohort study analysis using a multivariate generalized linear mixed model revealed that especially for most symptom scales, patients who underwent ESD had significantly better HRQOL scales than those who underwent surgery. We also assessed serial changes in HRQOL at each follow-up visit. At 1-month post-treatment, most functional and symptom HRQOL scales were significantly better in the ESD group than in the surgery group. However, except for physical functioning, diarrhea, and body image the differences between the two groups became insignificant during the 24-month follow-up.

Excellent long-term oncologic outcomes have been reported for EGC patients who underwent endoscopic resection or surgery for tumors meeting absolute or expanded indications; 5-year overall survival rates range from 94 to 97% [18,19,20]. Thus, HRQOL seems to be an important factor that affects whether a patient chooses ESD or surgery. However, despite increased interest in HRQOL after EGC treatment, few studies have compared HRQOL differences between ESD and surgery for EGC management. Choi et al. recently found that compared with surgery, ESD provides a better HRQOL for most symptom scales [12]. Despite the better HRQOL, however, the patients who underwent ESD had more concerns about cancer recurrence. However, this study used a cross-sectional design, and long-term serial HRQOL assessments were not performed during the follow-up period. Moreover, most of reported symptom scales had scores > 40 in both treatment groups, which was much higher than those in previous studies of HRQOL after surgery. In previous studies of EGC and advanced gastric cancer, most symptom scales had scores < 40 [4, 5, 9, 10]. Another recent prospective single-arm study revealed that HRQOL was not impaired even during the immediate post-ESD period, and was significantly improved up to 6-month post-treatment compared with baseline values [21]. However, this study has a limitation that it did not evaluate HRQOL after ESD compared with after surgery.

In the present study, during the early post-treatment period after ESD, most of the HRQOL parameters were significantly better than those after surgery. The significant HRQOL differences may be due to as follows: First, most functional and symptom HRQOL parameters were impaired during early post-surgery periods; this result was similar to the results of previous studies [4,5,6, 9, 10] Second, during the early period after gastrectomy, a patient’s HRQOL may be affected by post-gastrectomy syndrome. This syndrome develops as a result of gastric resection and the corresponding reconstruction of the upper gastrointestinal tract. It is associated with various symptoms (e.g., weight loss, dumping syndrome (abdominal pain and diarrhea), delayed gastric emptying, and reflux) [2]. Third, a higher risk of early severe complications after surgery might be also associated with poor HRQOL [19, 20, 22, 23]. Finally, in the ESD group, compared with HRQOL at the baseline visit, global health status and emotional functioning were significantly improved after treatment. It may be related to psychological HRQOL deterioration at baseline due to worry about treatment and prognosis at the time of EGC diagnosis. The remaining functional and symptom HRQOL parameters were not impaired after ESD most probably because the stomach was preserved after ESD. These early improvements in HRQOL after ESD were also reported in a recent article [21].

The results of our study indicated that most of the HRQOL functional and symptom scales in the surgery group that were impaired during the early follow-up period had recovered to those of baseline starting from the 6- to 12-month follow-ups. Previous studies also found that most of the HRQOL parameters that are impaired early after surgery recover to baseline levels at 12 months [6, 8,9,10]. This pattern in HRQOL improvement occurs both after open gastrectomy and less invasive laparoscopic gastrectomy during the long-term follow-up period [4, 24]. In addition, most of the symptoms related to post-gastrectomy syndrome improve or recover within 12 months after surgery [2, 25]. Our study results indicated that most significant early deteriorations in HRQOL parameters after surgery recovered after 12 months; the between-group differences (ESD vs. surgery) became statistically insignificant.

Although most HRQOL parameters tended to improve by 12 months after surgery, several parameters including the symptom scale factors of body image, fatigue, dysphagia, diarrhea, and eating restrictions did not recover [5, 6, 10, 26]. A recent more long-term follow-up study also found that the functional scales of physical, role, emotional, cognitive functioning, and body image, and the symptom scales of diarrhea, dysphagia, reflux symptoms, and eating restrictions remain significantly impaired until 5 years after gastrectomy compared with the preoperative scales [26]. In our study, the role functioning, fatigue, diarrhea, dysphagia, eating restrictions, anxiety, and body image of the surgery group were still impaired at the 24-month follow-up, compared with baseline levels. In addition, compared with HRQOL parameters of the ESD group, diarrhea, physical functioning, and body image were consistently impaired until 24 months in the surgery group. Full recovery from those long-term symptoms impairment in the surgery group seems to be problematic because they were mostly consequences of the gastrectomy and reconstruction of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

The strength of this study was that serial changes in post-ESD HRQOL were compared with those after surgery using a prospective cohort study design and a 24-month follow-up. However, this study had several limitations. First, selection bias was not avoidable. The surgery group had significantly larger tumor size, more advanced disease (more T1b and N1) and higher proportion of undifferentiated histologic types than the ESD group, because the enrolled patients were not randomly assigned to each treatment group. These differences might affect to the worse HRQOL in the surgery group. Thus, a prospective randomized trial is needed to investigate intermediate and long-term HRQOL changes between the both groups. Second, the number of ESD group patients was relatively small; it consisted of only one-half of the number of surgery group patients. Third, various types of surgical treatments were included in the surgery group, such as total or subtotal gastrectomy and laparoscopic or open surgery. Previous studies have found that patients who undergo total gastrectomy have more impaired HRQOL compared with those who undergo a subtotal gastrectomy [5], and laparoscopic surgery results in better HRQOL than open surgery [4, 6, 10]. Further studies are needed to compare the HRQOL of ESD with surgery using groups of patients who undergo the same types of surgery.

In conclusion, compared with surgery, ESD can provide better intermediate-term HRQOL after treatment of EGC patients, mainly because of the organ preservation. During the early post-treatment period, most of the HRQOL scales of patients who underwent ESD were significantly better than in those who underwent surgery. However, by the end of the 24-month follow-up period, the deteriorated HRQOL characteristics in the patients who underwent surgery did improve; only the physical functioning, body image, and diarrhea scales remained impaired compared with those who received ESD. The use of surgical treatment for EGC patients should not be rejected only because of concerns about early post-surgery HRQOL impairment.

References

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2011) Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer 14:113–123

Bolton JS, Conway WC 2nd (2011) Postgastrectomy syndromes. Surg Clin North Am 91:1105–1122

Tomita R, Fujisaki S, Tanjoh K, Fukuzawa M (2000) Relationship between gastroduodenal interdigestive migrating motor complex and quality of life in patients with distal subtotal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Int Surg 85:118–123

Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, Bae JM (2008) Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 248:721–727

Kim AR, Cho J, Hsu YJ, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Yun YH, Kim S (2012) Changes of quality of life in gastric cancer patients after curative resection: a longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Ann Surg 256:1008–1013

Misawa K, Fujiwara M, Ando M, Ito S, Mochizuki Y, Ito Y, Onishi E, Ishigure K, Morioka Y, Takase T, Watanabe T, Yamamura Y, Morita S, Kodera Y (2015) Long-term quality of life after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective multi-institutional comparative trial. Gastric Cancer 18:417–425

Avery K, Hughes R, McNair A, Alderson D, Barham P, Blazeby J (2010) Health-related quality of life and survival in the 2 years after surgery for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 36:148–154

Karanicolas PJ, Graham D, Gonen M, Strong VE, Brennan MF, Coit DG (2013) Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg 257:1039–1046

Kong H, Kwon OK, Yu W (2012) Changes of quality of life after gastric cancer surgery. J Gastric Cancer 12:194–200

Kobayashi D, Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Koike M, Nakayama G, Nakao A (2011) Assessment of quality of life after gastrectomy using EORTC QLQ-C30 and STO22. World J Surg 35:357–364

Lee JH, Kim JG, Jung HK, Kim JH, Jeong WK, Jeon TJ, Kim JM, Kim YI, Ryu KW, Kong SH, Kim HI, Jung HY, Kim YS, Zang DY, Cho JY, Park JO, Lim DH, Jung ES, Ahn HS, Kim HJ (2014) Clinical practice guidelines for gastric cancer in Korea: an evidence-based approach. J Gastric Cancer 14:87–104

Choi JH, Kim ES, Lee YJ, Cho KB, Park KS, Jang BK, Chung WJ, Hwang JS, Ryu SW (2015) Comparison of quality of life and worry of cancer recurrence between endoscopic and surgical treatment for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 82:299–307

Lee JY, Choi IJ, Cho SJ, Kim CG, Kook MC, Lee JH, Ryu KW, Kim YW (2012) Routine follow-up biopsies after complete endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer may be unnecessary. J Gastric Cancer 12:88–98

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365–376

Yun YH, Park YS, Lee ES, Bang SM, Heo DS, Park SY, You CH, West K (2004) Validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 13:863–868

Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, Vickery C, Arraras J, Sezer O, Moore J, Koller M, Turhal NS, Stuart R, Van Cutsem E, D’haese S, Coens C; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal and Quality of Life Groups (2004) Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 40:2260–2268

Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B (2000) Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology 11:550–560

Choi IJ, Lee JH, Kim YI, Kim CG, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Ryu KW, Nam BH, Kook MC, Kim YW (2015) Long-term outcome comparison of endoscopic resection and surgery in early gastric cancer meeting the absolute indication for endoscopic resection. Gastrointest Endosc 81:333–341

Kim YI, Kim YW, Choi IJ, Kim CG, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Eom BW, Yoon HM, Ryu KW, Kook MC (2015) Long-term survival after endoscopic resection versus surgery in early gastric cancers. Endoscopy 47:293–301

Pyo JH, Lee H, Min BH, Lee JH, Choi MG, Lee JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Kim KM, Ahn JH, Carriere KC, Kim JJ, Kim S (2016) Long-Term Outcome of Endoscopic Resection vs. Surgery for Early Gastric Cancer: a non-inferiority-matched cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 111:240–249

Kim SG, Ji SM, Lee NR, Park SH, You JH, Choi IJ, Lee WS, Park SJ, Lee JH, Seol SY, Kim JH, Lim CH, Cho JY, Kim GH, Chun HJ, Lee YC, Jung HY, Kim JJ (2017) Quality of life after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Gut Liver 15:87–92

Choi KS, Jung HY, Choi KD, Lee GH, Song HJ, Kim DH, Lee JH, Kim MY, Kim BS, Oh ST, Yook JH, Jang SJ, Yun SC, Kim SO, Kim JH (2011) EMR versus gastrectomy for intramucosal gastric cancer: comparison of long-term outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc 73:942–948

Cho JH, Cha SW, Kim HG, Lee TH, Cho JY, Ko WJ, Jin SY, Park S (2016) Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a comparison study to surgery using propensity score-matched analysis. Surg Endosc 30:3762–3773

Kim YW, Yoon HM, Yun YH, Nam BH, Eom BW, Baik YH, Lee SE, Lee Y, Kim YA, Park JY, Ryu KW (2013) Long-term outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: result of a randomized controlled trial (COACT 0301). Surg Endosc 27:4267–4276

Pedrazzani C, Marrelli D, Rampone B, De Stefano A, Corso G, Fotia G, Pinto E, Roviello F (2007) Postoperative complications and functional results after subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II reconstruction for primary gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci 52:1757–1763

Yu W, Park KB, Chung HY, Kwon OK, Lee SS (2016) Chronological changes of quality of life in long-term survivors after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cancer Res Treat 48:1030–1036

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Grant 1610180 and 0410150 from the National Cancer Center, Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: Young Ho Yun and Il Ju Choi. Writing and revision of the manuscript: Young-Il Kim, Young Ae Kim, and Il Ju Choi. Acquisition of data and critical revision: Chan Gyoo Kim, Keun Won Ryu, Young-Woo Kim, Young Ho Yun, and Il Ju Choi. Statistical analysis: Young Ae Kim and Jin Ah Sim.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Young-Il Kim, Young Ae Kim, Chan Gyoo Kim, Keun Won Ryu, Young-Woo Kim, Jin Ah Sim, Young Ho Yun, and Il Ju Choi have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Additional information

Young-Il Kim and Young Ae Kim contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, YI., Kim, Y.A., Kim, C.G. et al. Serial intermediate-term quality of life comparison after endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery in early gastric cancer patients. Surg Endosc 32, 2114–2122 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5909-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5909-y