Abstract

Background

Although pain is a common complication of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), management strategies are inadequate. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of topical bupivacaine and triamcinolone acetonide for abdominal pain relief and as a potential method of pain control after ESD for gastric neoplasia.

Methods

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 111 eligible patients with early gastric neoplasm were randomized into one of three groups: bupivacaine (BV) only, bupivacaine with triamcinolone (BV-TA), or placebo. The present pain intensity (PPI) score and the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) were used to evaluate pain at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h after ESD.

Results

The mean values for the 6-hour PPI in the BV-TA and BV groups were lower than those of the placebo group (1.57 ± 1.09 and 1.97 ± 1.09 vs. 2.63 ± 0.98, p < 0.001). The 12-hour PPI of the BV-TA group (1.20 ± 0.83) was the lowest among the three groups (p = 0.001). The total 6-hour SF-MPQ score, especially in the sensory domain, was higher in the placebo group than in BV and BV-TA groups. The 12-hour SF-MPQ score was the lowest in the BV-TA group. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that BV-TA injection protocol, fibrosis, and size of residual ulcer were independently associated with the PPI score at 6 h.

Conclusion

Bupivacaine after ESD was effective for pain relief at 6 h postoperatively. Particularly, topical infiltration of bupivacaine mixed with triamcinolone acetonide was helpful for producing a more long-lasting benefit of pain relief after gastric ESD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for pre-cancerous lesions of the stomach and early gastric cancer is an effective treatment [1]. However, it requires a high level of dexterity in endoscopic control. Thus, considerable training is required to obtain the skills necessary to perform the procedure [2]. Therefore, significant side effects occur often, since ESD is difficult to perform. Bleeding, perforations, and strictures are well-known adverse events of ESD [3]. However, although ESD is less invasive for gastric neoplasia than gastrectomy, the majority of patients complain, other than of these adverse events, of abdominal pain following ESD and it is the most common side effect of ESD. Further, there is a tendency for the pain that occurs after ESD to be relatively overlooked. Localized pain both during and after ESD for large lesions is probably caused by ulcer defects, transmural air leaks, and/or electrical thermal burns extending from the submucosa to the serosa [4–6].

Recently, pain has become an important factor used in evaluating both quality of life and the quality of the clinical approach. Inadequate pain control is a major cause of prolonged hospitalization after procedure and increased healthcare costs [7, 8]. Nevertheless, up to now, pain management strategies for ESD have been rare except in a few studies [9, 10].

Particularly, to overcome the problems and potential side effects of systemically administered oral and parental analgesics, local anesthetics administered at or around the ESD sites such as lidocaine have been studied [9]. Similar to lidocaine, bupivacaine is used for visceral pain control in chronic pain and in pain associated with surgery in clinical practice [11–17]. Further, triamcinolone, a type of steroid, is often mixed with bupivacaine to lengthen the analgesic effect.

By focusing on these points, in this study we compared the efficacy of topical bupivacaine injected alone or with triamcinolone acetonide in the relief of abdominal pain after ESD for gastric neoplasia.

Methods

Patients

The study protocol and informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practices and the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. This study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov under identifier NCT01961752.

Patients between the ages of 20 and 80 who were scheduled to undergo ESD for gastric epithelial neoplasm at Severance Hospital of Yonsei University between July 2012 and April 2013 were enrolled in this prospective, randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before study enrollment after the risks, benefits, alternatives to the procedure, and the purpose of the study were explained to the patients.

The exclusion criteria included (1) not providing written informed consent (2) a history of any cardiac arrhythmias, (3) current or regular use of analgesic medication for other indications, (4) known other diseases such as peptic ulcer disease or reflux esophagitis which could induce upper gastrointestinal pain, (5) multiple lesions requiring ESD in a single patient, (6) evidence of infectious disease or antibiotics therapy within 7 days prior to enrollment, (7) participation in another clinical trial within 30 days prior enrollment, (8) current pregnancy or breast feeding.

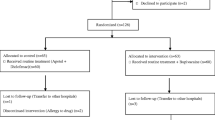

In total, 111 consecutive eligible patients were randomized into only the bupivacaine (BV) group (n = 37), the bupivacaine with triamcinolone (BV-TA) group (n = 37), and the placebo group (n = 37). Among these, 12 patients (10.8 %) were excluded from the study after enrollment. Ten patients were excluded due to failure to complete the questionnaire, one had a bowel perforation during ESD, and one had unexpected multiple lesions. Therefore, 99 patients were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Study flow. Initially, 130 patients who were scheduled to undergo ESD for a gastric epithelial neoplasm were enrolled in the screening. Nineteen patients were excluded due to absence of informed consent (n = 3), multiple lesions (n = 6), arrhythmia (n = 3), and NSAID use (n = 7). In total, 111 consecutive eligible patients were randomized into three groups. Among them, 12 patients (10.8 %) dropped out after enrollment

Randomization and masking

Subjects were stratified into three groups based on locally injected substances. Patients were randomly assigned in a one-to-one ratio to the groups according to a computer-generated randomization list.

The allocation was concealed from the researchers assessing and enrolling participants. Allocation occurred after the sedation of the patient. The solutions were prepared according to the randomization schedule by a third physician who was involved as an assistant. This physician administered a 30-mL syringe injection to the patients just before the ESD was finished. The patient, endoscopist, and research nurse (who assessed follow-up evaluation) were all blinded to the treatment allocation until completion of the analysis.

ESD technique and local injection protocol

All ESDs were performed with a standard single-channel endoscope (GIF-Q260J or GIF-H260Z, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). After making several marking dots circumferentially outside the lesion using a needle knife (KD-10Q-1-A, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), a saline solution containing epinephrine (0.01 mg/mL) and 0.8 % indigo carmine was injected into the submucosal layer to lift the lesion off the muscle layer. A circumferential incision and dissection was made using a needle knife and an insulated-tip knife (KD-610L, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Endoscopic hemostasis was performed whenever bleeding or exposed vessels were observed.

The local injection was performed using bupivacaine (5 mg/mL), triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/mL), or saline according to the group just before the ESD was finished. A mixture of 10 mL bupivacaine (total 50 mg) and 5 mL saline was administered to the BV group, a mixture of 10 mL bupivacaine (total 50 mg) and 5 mL triamcinolone acetonide (total 50 mg) was administered to the BV-TA group, and 15 mL saline alone was administered to the placebo group. Each solution was delivered through the endoscopy suite and injected into the cautery ulcer base in aliquots of 1 mL at equal intervals (1 cm apart). The number of injections per patient was dependent on the size of resection, and the total dose of bupivacaine or triamcinolone ranged from 20 to 50 mg. All cases of ESD procedures and study protocols were performed by one experienced endoscopist (H.L.).

For evaluation of side effects, a second-look endoscopy was performed 2 days after the ESD, and the condition of the ulcer base was categorized as follows: clean base, black spot, adherent clot, non-bleeding visible vessel, and oozing bleeding. Perforations were checked using a simple abdominal X-ray, which was performed immediately after ESD, and cardiac arrhythmias were evaluated by continuous ECG monitoring during and after the procedure.

Main outcome measurements

Present pain intensity (PPI) score and the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) were used to evaluate pain following ESD. Pain scales were assessed at the following points: immediately after ESD and 6, 12, and 24 h after ESD. In this study, the primary efficacy variable was PPI score at 6 h, and secondary efficacy variables were PPI scores at 0, 12, and 24 h and the SF-MPQ result.

The PPI score was derived from the Likert-type scale and ranged from 0 to 5 (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = discomforting, 3 = distressing, 4 = horrible, and 5 = excruciating). The SF-MPQ, a shorter version of the MPQ, is a multidimensional measure of perceived pain in adults. The SF-MPQ is comprised of 15 words (11 sensory and 4 affective) from the original MPQ which are rated on an intensity scale as 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe [18].

Statistical analysis

We performed a pilot study and the mean PPI score at 6 h (as a primary outcome) was 2.85 in the placebo group, 2.21 in the BV-TA group, and 2.50 in the BV group. The primary hypothesis was that “topical bupivacaine and triamcinolone acetonide injection are effective in reducing the PPI score at 6 h after ESD.” Based on power calculations, we determined that 37 patients in each group would be required to test the hypothesis with 80 % power, a 5 % significance level, and a 15 % drop-out rate.

Analysis of the primary efficacy variable was conducted by intention-to-treat analysis, and handling of missing values was determined by last-observation-carried forward analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables or number (%) for categorical variables. For comparisons of three groups, the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical factors, and the one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Bonferroni’s test was used for continuous variables. In univariate analyses, to evaluate the factors affecting the PPI score, the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables were used. In multivariate analysis, binomial logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the factors affecting the PPI score. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS 18.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Group baseline characteristics

Among total 99 patients who were finally included in the analysis of this study, there were 32 patients in the BV group, 35 patients in the BV-TA group, and 32 patients in the placebo group. The baseline characteristics of the three groups are summarized in Table 1. Compared to the placebo group, the BV group and the BV-TA group were not different in terms of baseline characteristics except for using IV painkillers, which was higher in the placebo group [BV-TA group vs. BV group vs. placebo group: 6 (17.1 %) vs. 10 (31.3 %) vs. 15 (46.9 %), respectively, p = 0.032]. Comparing the three groups, patient-related factors (age, sex, BMI, and Helicobacter pylori infection), neoplasia-related factors (tumor location, final pathology, and submucosal invasion), and procedure-related factors (procedure time, bleeding, fibrosis, en bloc resection, and complete resection) were not significantly different (Table 1).

Comparison of the pain score between the groups

The PPI score after ESD is shown in Fig. 2A. The score at 6 h was significantly lower in both the BV-TA group and the BV group than that in the placebo group (BV-TA group vs. placebo group: 1.57 ± 1.09 vs. 2.63 ± 0.98, respectively, p < 0.001; and BV group vs. placebo group: 1.97 ± 1.09 vs. 2.63 ± 0.98, respectively, p = 0.044). The score at 12 h was significantly lower only in the BV-TA group, but not in the BV group, compared to the placebo group (BV-TA group vs. placebo group: 1.20 ± 0.83 vs. 2.09 ± 0.96, respectively, p = 0.001; and BV group vs. placebo group: 1.75 ± 1.08 vs. 2.09 ± 0.96, p = 0.465, respectively).

The mean pain score with time flow exhibit the difference at 6 and 12 h in present pain intensity (PPI), total and sensory Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) between the groups; A The score at 6 h was significantly lower in both bupivacaine with triamcinolone (BV-TA) group and only-bupivacaine (BV) group than placebo group (BV-TA group vs. placebo group; 1.57 ± 1.09 vs. 2.63 ± 0.98, p < 0.001 and BV group vs. placebo group 1.97 ± 1.09 vs. 2.63 ± 0.98, p = 0.044, respectively). The score at 12 h was significantly lower only in BV-TA group, not in BV group, than placebo (BV-TA group vs. placebo group; 1.20 ± 0.83 vs. 2.09 ± 0.96, p = 0.001). B, C In total and sensory SF-MPQ score, the mean value at 6 h was significantly lower in BV-TA group and BV group than placebo group (in total SF-MPQ; 9.09 ± 2.39 and 9.13 ± 3.48 vs. 11.06 ± 3.46, p = 0.017 and in sensory SF-MPQ; 8.66 ± 2.34 and 8.59 ± 3.20 vs. 10.50 ± 3.13, p = 0.013, respectively), and the score at 12 h was significantly lower only in BV-TA group than placebo (in total SF-MPQ; 5.80 ± 2.67 vs. 7.94 ± 2.06, p = 0.001 and in sensory SF-MPQ; 5.43 ± 2.59 vs. 7.43 ± 2.31, p = 0.003, respectively). D In affective MPS score, there was no difference at both 6 and 12 h in mean pain score between groups (p = 0.738 and p = 0.752, respectively)

Similarly, for the total and sensory SF-MPQ score, the mean value at 6 h was significantly lower in the BV-TA group and the BV group than in the placebo group (BV-TA group vs. placebo group in total SF-MPQ: p = 0.034, and in sensory SF-MPQ: p = 0.033; BV group vs. placebo group in total SF-MPQ: p = 0.045, and in sensory SF-MPQ: p = 0.030), and the score at 12 h was significantly lower only in the BV-TA group, but not in the BV group, compared to the placebo group (BV-TA group vs. placebo group in total SF-MPQ: p = 0.001, and in sensory SF-MPQ: p = 0.003) (Fig. 2B, C). However, for the affective MPS score, there were no differences at both 6 and 12 h in the mean pain scores between the three groups (p = 0.738 and p = 0.752, respectively) (Fig. 2D).

Factors affecting the PPI score after ESD

To evaluate the factors affecting pain, the PPI score was divided into none-mild-discomforting pain (PPI 0–2) and distressing-horrible-excruciating pain (PPI 3–5). When the PPI score at 6 h was classified into two these groups, the frequency in each randomized group was significantly different. PPI was 29 (82.9 %) in the BV-TA group, 22 (68.8 %) in the BV group, and 14 (43.8 %) in the placebo group (p = 0.003) (Fig. 3).

Frequency of the present pain intensity (PPI) score in each randomized group. When the PPI score at 6 h was classified as either low or high, the percent of patients in each group having a high or low score was significantly different. 0–2 PPI was 29 (82.9 %) in bupivacaine with triamcinolone group, 22 (68.8 %) in only-bupivacaine group, and 14 (43.8 %) in placebo group (p = 0.003)

In univariate analysis, the PPI score at 6 h was associated with the groups, the size of the residual ulcer, and the procedural time (p = 0.003, p < 0.001, and p = 0.016, respectively). The PPI score at 12 h was associated with the groups and the size of the residual ulcer (p = −0.002 and p = 0.017, respectively) (Table 2).

In multivariate analysis, topical BV-TA injection lowered the PPI score more at 6 and 12 h than the placebo (OR: 0.068, 95 % CI: 0.011−0.140, p = 0.003; and OR: 0.073, 95 % CI: 0.013−0.393, p = 0.002; respectively). In addition, minimal fibrosis lowered the PPI score at 6 h more than severe fibrosis (OR: 0.034, 95 % CI: 0.002−0.591, p = 0.020). Similarly to the result of the univariate analysis, the size of residual ulcer increased the PPI score at 6 h in multivariate analysis (OR: 1.007, 95 % CI: 1.004−1.010, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Side effects

Bleeding was evaluated by a second-look endoscopy, which was conducted in 88 of 99 patients (88.9 %) at 2 days after the ESD. There were no differences in the second-look endoscopic finding between the three groups (p = 0.833) (Table 1). There was no demonstrable side effect of the local anesthetic solution injection in this study.

Discussion

This is the first trial demonstrating that topical BV-TA injection is effective for management of abdominal pain after ESD. Acute inflammatory responses that occur after ESD lead to mainly two types of adverse events: one adverse event is strictures and the other adverse event is pain. Among them, stricture prevention through anti-inflammatory management has been suggested in several studies [19, 20]. Although there have been a few reports about the inflammatory mechanism involved in pain, some reported cases have shown that pain could be caused by severe inflammation [21, 22]. Moreover, even if it is not that critical of a complication, various degrees of symptoms in pain caused by the inflammatory response seem common. We have previously reported that the incidence of patients with pyrexia and upper abdominal pain or tenderness after ESD is 7.1 % of all ESD cases [4],

There have been many studies about local anesthetic agents for visceral pain control, especially those targeting intra-abdominal surgery or the celiac axis [11, 14, 23–25]. In terms of ESD-related research, there exists a lidocaine injection study [9]. In terms of local anesthetic agents commonly employed for regional anesthesia, the effectiveness of bupivacaine, which is longer acting and stronger compared with lidocaine [26], only one study has been reported [27]. Considering these studies, we tested bupivacaine with steroid mix injection for relieving post-ESD pain. We found that local BV-TA injection had the effect of lessening systemic painkiller use during the immediate period after ESD. Moreover, it significantly lowered the mean pain scores at 6 and 12 h. For example, the PPI score was lowered compared to the placebo from 2.63 ± 0.98 to 1.57 ± 1.09 at 6 h and from 2.09 ± 0.96 to 1.20 ± 0.83 at 12 h. In addition, after adjustment for multiple variables, BV-TA injection was associated with a lower PPI score at 6 h and 12 h (OR: 0.068, 95 % CI: 0.011−0.140, p = 0.003; and OR: 0.073, 95 % CI: 0.013−0.393, p = 0.002; respectively).

Even though the mechanism of the bupivacaine effects is not clear, it is thought to work by local nerve block to the enteric nerve system, which is composed of the myenteric plexus and the submucosal plexus [28]. In particular, the extended analgesic effect when mixed with steroids is consistent with past findings [29]. Especially, in multivariate analysis, the size of the residual ulcer and fibrosis was associated with the pain score and meaningful factors for the pain control protocol they were identified. This is likely because the electrical current was administered for a longer time during the procedure.

Local TA injection into the floor of a post-ESD artificial gastric ulcer has been frequently used after some clinical trials which were reported the effectiveness in preventing pyloric stenosis and deformity following large ESD [30, 31]. In addition, there were very few reports of systemic side effects such as latent infections or allergic reactions in the level of reported cases only [32]. Also, there was no demonstrable side effect of locally administrated TA in this study. It seemed reasonable and safe to treat with local TA injection into a post-ESD ulcer in the respect of systemic side effect.

A limitation of this study is that lack of mechanistic understanding of how combination bupivacaine and steroid help with pain control. Therefore, further studies with analyses of various biomarkers of pain or inflammation are necessary. Nevertheless, this is the first study to suggest aggressive management for post-ESD pain. Through intralesional bupivacaine, pain after ESD was improved. Particularly, with steroid use, the effect of pain control was maximized by the anti-inflammatory effect and the duration of effect of bupivacaine was extended.

In conclusion, combined topical bupivacaine and triamcinolone acetonide injection have the potential to offer relief for abdominal pain after ESD for gastric neoplasia.

References

Park YM, Cho E, Kang HY, Kim JM (2011) The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc 25(8):2666–2677

Yamamoto H (2012) Endoscopic submucosal dissection—current success and future directions. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9(9):519–529

Probst A, Pommer B, Golger D, Anthuber M, Arnholdt H, Messmann H (2010) Endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric neoplasia—experience from a European center. Endoscopy 42(12):1037–1044

Lee H, Cheoi KS, Chung H, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC (2012) Clinical features and predictive factors of coagulation syndrome after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasm. Gastric Cancer 15(1):83–90

Cha JM, Lim KS, Lee SH, Joo YE, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim HG, Park DI, Kim SE, Yang DH, Shin JE (2013) Clinical outcomes and risk factors of post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective, case-control study. Endoscopy 45(3):202–207

Onogi F, Araki H, Ibuka T, Manabe Y, Yamazaki K, Nishiwaki S, Moriwaki H (2010) “Transmural air leak”: a computed tomographic finding following endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric tumors. Endoscopy 42(6):441–447

Turk DC (2002) Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments for patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 18(6):355–365

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R (2003) Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA 290(18):2443–2454

Kiriyama S, Oda I, Nishimoto F, Mashimo Y, Ikehara H, Gotoda T (2009) Pilot study to assess the safety of local lidocaine injections during endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 12(3):142–147

Choi HS, Kim KO, Chun HJ, Keum B, Seo YS, Kim YS, Jeen YT, Um SH, Lee HS, Kim CD, Ryu HS (2012) The efficacy of transdermal fentanyl for pain relief after endoscopic submucosal dissection: a prospective, randomised controlled trial. Dig Liver Dis 44(11):925–929

Kahokehr A, Sammour T, Srinivasa S, Hill AG (2011) Systematic review and meta-analysis of intraperitoneal local anaesthetic for pain reduction after laparoscopic gastric procedures. Br J Surg 98(1):29–36

Santosh D, Lakhtakia S, Gupta R, Reddy DN, Rao GV, Tandan M, Ramchandani M, Guda NM (2009) Clinical trial: a randomized trial comparing fluoroscopy guided percutaneous technique vs. endoscopic ultrasound guided technique of coeliac plexus block for treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 29(9):979–984

Stevens T, Costanzo A, Lopez R, Kapural L, Parsi MA, Vargo JJ (2012) Adding triamcinolone to endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus blockade does not reduce pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10(2):186–191 191 e181

Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Wiersema MJ, Clain JE, Rajan E, Wang KK, de la Mora JG, Gleeson FC, Pearson RK, Pelaez MC, Petersen BT, Vege SS, Chari ST (2008) Initial evaluation of the efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided direct Ganglia neurolysis and block. Am J Gastroenterol 103(1):98–103

Ganta R, Samra SK, Maddineni VR, Furness G (1994) Comparison of the effectiveness of bilateral ilioinguinal nerve block and wound infiltration for postoperative analgesia after caesarean section. Br J Anaesth 72(2):229–230

Feroci F, Kroning KC, Scatizzi M (2009) Effectiveness for pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy of 0.5 % bupivacaine-soaked Tabotamp placed in the gallbladder bed: a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Surg Endosc 23(10):2214–2220

Roberts KJ, Gilmour J, Pande R, Nightingale P, Tan LC, Khan S (2011) Efficacy of intraperitoneal local anaesthetic techniques during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 25(11):3698–3705

Wright KD, Asmundson GJ, McCreary DR (2001) Factorial validity of the short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ). Eur J Pain 5(3):279–284

Hanaoka N, Ishihara R, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Higashino K, Ohta T, Kanzaki H, Hanafusa M, Nagai K, Matsui F, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Ito Y (2012) Intralesional steroid injection to prevent stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection for esophageal cancer: a controlled prospective study. Endoscopy 44(11):1007–1011

Hashimoto S, Kobayashi M, Takeuchi M, Sato Y, Narisawa R, Aoyagi Y (2011) The efficacy of endoscopic triamcinolone injection for the prevention of esophageal stricture after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc 74(6):1389–1393

Lee BS, Kim SM, Seong JK, Kim SH, Jeong HY, Lee HY, Song KS, Kang DY, Noh SM, Shin KS, Cho JS (2005) Phlegmonous gastritis after endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy 37(5):490–493

Probst A, Maerkl B, Bittinger M, Messmann H (2010) Gastric ischemia following endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 13(1):58–61

Nicholson G, Hall GM (2011) Effects of anaesthesia on the inflammatory response to injury. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 24(4):370–374

Wong GY, Schroeder DR, Carns PE, Wilson JL, Martin DP, Kinney MO, Mantilla CB, Warner DO (2004) Effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block on pain relief, quality of life, and survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291(9):1092–1099

Boddy AP, Mehta S, Rhodes M (2006) The effect of intraperitoneal local anesthesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 103(3):682–688

Covino BG (1986) Pharmacology of local anaesthetic agents. Br J Anaesth 58(7):701–716

Concepcion M, Covino BG (1984) Rational use of local anaesthetics. Drugs 27(3):256–270

Galligan JJ (2004) Enteric P2X receptors as potential targets for drug treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Pharmacol 141(8):1294–1302

Castillo J, Curley J, Hotz J, Uezono M, Tigner J, Chasin M, Wilder R, Langer R, Berde C (1996) Glucocorticoids prolong rat sciatic nerve blockade in vivo from bupivacaine microspheres. Anesthesiology 85(5):1157–1166

Mori H, Rafiq K, Kobara H, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Kobayashi M, Himoto T, Haba R, Hagiike M, Izuishi K, Okano K, Suzuki Y, Masaki T (2012) Local steroid injection into the artificial ulcer created by endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer: prevention of gastric deformity. Endoscopy 44(7):641–648

Fujiwara S, Morita Y, Toyonaga T, Kawakami F, Itoh T, Yoshida M, Kutsumi H, Azuma T (2011) A randomized controlled trial of rebamipide plus rabeprazole for the healing of artificial ulcers after endoscopic submucosal dissection. J Gastroenterol 46(5):595–602

Mori H, Fujihara S, Nishiyama N, Kobara H, Oryu M, Kato K, Rafiq K, Masaki T (2013) Cytomegalovirus-associated gastric ulcer: a side effect of steroid injections for pyloric stenosis. World J Gastroenterol 19(7):1143–1146

Disclosures

Drs. B.Kim, H.S.Chung, J.C.Park, S.K.Shin, S.K.Lee, Y.C.Lee, and H.Lee have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov under identifier NCT01961752.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, B., Lee, H., Chung, H. et al. The efficacy of topical bupivacaine and triamcinolone acetonide injection in the relief of pain after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasia: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Surg Endosc 29, 714–722 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3730-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3730-4