Abstract

Background

Rectal carcinoids are increasing in incidence worldwide. Frequently thought of as a relatively benign condition, there are limited data regarding optimal treatment strategies for both localized and more advanced disease. The aim of this study was to summarize published experiences with rectal carcinoids and to present the most current data.

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines, an electronic literature search performed of PubMed, Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Library using the terms “rectum” or “rectal” AND “carcinoid” over a 20-year study period from January 1993 to May 2013. Non-English-language studies, animal studies, and studies of fewer than 100 patients were excluded. Study end points included demographic information, tumor features, intervention and outcomes. All included articles were quality assessed.

Results

Using the search parameters and exclusions as outlined above, a total of 14 articles were identified for detailed analysis. The quality of articles was low/moderate for all included scoring 9 to 17 of 27. The articles included 4,575 patients diagnosed with a rectal carcinoid. Approximately 80 % of tumors were <10 mm, 15 % 11–20 mm, and 5 % >20 mm. Eight percent of patients presented with regional lymph node metastases, and 4 % presented with distant metastases. Tumor size >10 mm, and muscular and lymphovascular invasion are independently associated with an increased risk of metastases. The 5-year survival was 93 % in patients presenting with localized disease and 86 % overall.

Conclusions

Small tumors up to 10 mm without any adverse features can be treated with endoscopic or local excision. The treatment of carcinoids between 10 and 20 mm is still contentious, but those up to 16 mm without adverse feature are suitable for local/endoscopic excision followed by careful histopathological assessment. Those >20 mm or with adverse features require radical surgery with mesorectal clearance in suitable patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Carcinoids were first described in 1867 [1] and defined histopathologically in 1888 [2]. The term carcinoid, which means “carcinoma-like,” was coined in 1907 [3]. Rectal carcinoid tumors continue to be an elusive condition with unclear guidelines or best evidence for treatment modalities, and there is ongoing debate regarding the nomenclature of neuroendocrine tumors [4]. Despite being relatively uncommon compared to rectal adenocarcinoma, there is evidence that the incidence of rectal carcinoid is increasing [5–7], perhaps related to increased diagnostics with more access to endoscopy. Although rectal carcinoids often behave in a relatively indolent manner, they are malignant and can metastasize, as reflected in the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification [8]. In a large US series, the 5-year survival rate in patients for all carcinoids was 67 % and for rectal carcinoids was 88 %. Clearly this is not a benign condition; therefore, it must be appropriately managed and treated to reduce the risk of local and distant metastases.

There is a plethora of literature comparing different traditional and novel endoscopic treatments, but few articles provide robust data detailing their optimal treatment in terms of whether local excision, endoscopic treatment, or more radical surgery with mesorectal excision is appropriate.

The aim of this article was to systematically review the literature to present the most up-to-date information on this challenging condition.

Methods

Following PRISMA guidelines, an electronic literature search was performed of PubMed, Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane Library using the terms “rectum” or “rectal” and “carcinoid” over a 20-year study period from January 1993 to May 2013. Non-English-language studies, animal studies, and studies of fewer than 100 patients were excluded. Study end points included demographic information, tumor features, intervention, and outcomes. Further studies were identified from searches on Google Scholar, as well as manual searches through reference lists of the relevant studies found.

Because of the heterogeneity of data, a meta-analysis could not be performed, and articles were therefore analyzed qualitatively. DW arbitrated disputes on the inclusion or exclusion of articles. Articles were assessed for quality using the Downs and Black questionnaire for randomized and nonrandomized trials by FM and AH and were discussed to reach a consensus [9].

Results

A total of 425 articles were retrieved with the initial search and exclusion criteria. After abstract review, 77 articles were identified. Fifteen of these were kept for more detailed review; the others were either not relevant (n = 47) or were review articles (n = 14) (Fig. 1).

PRISMA diagram [10]

The 15 articles represented 1 meta-analysis, 11 case series (9 single center and 2 multicenter), and 3 articles publishing registry data. The majority (n = 12) were from Asia, with 2 from the United States and 1 international collaboration (Europe/United States). There were no randomized control trials. Out of the 3 registry publications, 2 used the same source of data with overlapping time periods. For the purpose of analysis, the publication by Modlin et al. [7] was chosen in preference to Maggard et al. [11] because it covered a longer time period and had larger numbers. Therefore, there were 14 articles evaluated in this review. All 14 articles scored low to moderate on quality assessment, with a range of 9–17 out of a possible 27 [9] (Table 1; Appendix).

Demographics and tumor size

We excluded case series with fewer than 100 patients; the smallest series included had 100 patients and the largest was from registry data with 1,481 patients (Table 1) [7, 19]. The total number of patients from all studies was 4,575. The median age was 51.2 (range, 47.7–57.6) years for all studies, and there were more men (57 %) compared with women (43 %). The majority of tumors (79 %) were less than 10 mm in size compared with 16 % of those 10–20 mm in size and 5 % in those greater than 20 mm in size. Different studies quoted either mean or median; the mean tumor size in 8 studies was 6 mm (Table 2).

Staging

The data for staging were incomplete or not recorded in several of the studies [7, 13, 27, 28]. In fact, only 1,633 of 4,575 (36 %) had accurate staging recorded. Three studies analyzed a selected group of tumors up to the submucosa and are recorded in Table 3 but not analyzed [18–20]. A total of 1,260 of 1,418 (89 %) tumors were confined to the submucosa, 5 % invaded the muscularis propria, and 6 % were beyond the muscularis propria. A total of 104 of 1,637 (6 %) tumors had lymphovascular invasion, and 113 of 1,396 (8 %) had lymph node metastases. There was distant spread in 60 of 1,618 (4 %), but only 36 % of all the cases in this review were accurately staged.

Treatment

A total of 1,976 patients had their treatment accurately reported. A total of 1,540 (78 %) patients had endoscopic treatment; of these, 913 (46 %) had an unspecified endoscopic excision, 345 (17 %) endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), 197 (10 %) endoscopic submucosal resection (ESD), and 85 (4 %) endoscopic submucosal resection with a ligation device (ESMR-L). A total of 187 (9 %) patients had a local surgical excision, and 249 (13 %) underwent radical excision (Table 4). The type of radical excision was poorly reported in most articles.

Discussion

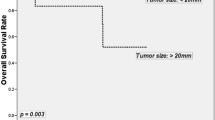

Rectal carcinoid tumors represent a challenging disease process. Although their incidence is increasing, most colorectal surgeons will see few cases in their career [29]. There is a misconception that rectal carcinoids behave in a benign fashion. Most will follow an indolent course, but there is a clear risk of local and distant metastases, with associated mortality. Although outcome for those with localized disease is excellent, there is a dramatic decline in outcomes for those with nodal disease and again for those with distant metastases. The 5-year survival was consistent with previously published literature at 86 % (range, 83–94 %) (Table 5).

The prevailing issue is how to manage a condition where the majority of patients will have a good prognosis but a certain proportion will need radical surgery to prevent distant spread. How do we stratify this subpopulation? The most commonly used tool is the size of the tumor. Traditionally, 10 mm, 10–20 mm, and >20 mm are used to classify carcinoid tumors to predict the risk of spread and to guide management and treatment.

The risk factors for metastases include tumors greater than 10 mm, atypical surface, patient age greater than 60 years, and muscular, perineural, or lymphovascular invasion [12, 18, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27]. This has been corroborated by meta-analyses in 3 articles that demonstrated that tumor size greater than 10 mm [21, 23], pT stage [12], and lymphovascular invasion were independently associated with an increased risk of metastatic disease [21, 23]. Factors associated with survival were tumor size [27], muscular invasion [25, 27], and the presence of metastases [27].

By the rationale of these articles, it would appear that smaller tumors could be safely treated by local means, i.e., endoscopic or local surgical excision. However, most series demonstrate local and distant metastases even in tumors of this size. In two series from the East, lymph node positivity was 2–5 % and the metastasis rate between 2 and 5 % [21, 22]. Metastases in distant organs were found in less than 5 % of patients with tumors less than 10 mm [24].

There are no definitive guidelines, but previous studies have suggested that local excision is safe if the tumor fulfills the following criteria: less than 10 mm, no invasion of muscularis propria and no ulceration [30], or less than 10 mm with adequate endoscopic surveillance [31].

An international collaboration on prospectively collected data found that tumors greater than 10 mm with lymphovascular invasion were significantly associated with nodal disease, necessitating mesorectal excision; smaller tumors can safely be removed with a local excision [23]. The 2013 article published by Kim et al. [12] concluded that T1a tumors (<1 cm and confined to lamina propria/submucosa) could be safely treated with local excision with the proviso that tumors are assessed for complete resection, depth of invasion, size, and lymphovascular invasion. This allows for radical salvage surgery, if appropriate.

The term carcinoid means “carcinoma-like,” and this adds to the confusion in their management. The term was necessary to distinguish carcinoids that usually behave in a more benign fashion compared to gastrointestinal carcinomas. Since then, carcinoids have been studied in greater detail, and new classification systems and histopathological markers have been identified. The World Health Organization (WHO) updated their classification system on carcinoids/neuroendocrine tumors [32], expanding the previous classification based on embryological origin, i.e., foregut, midgut, and hind gut. The 3 categories are neuroendocrine, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma. These are further graded into 3 groups on the basis of rates of proliferation, mitotic indices, or proportion that stain positive for the Ki-67 antigen. The smaller tumors with no adverse features, which are suitable for local excision, likely represent the relatively benign carcinoids—that is, those that would be graded 1 or 2 on the WHO classification. Those small tumors with adverse features or larger aggressive tumors that can present with pain represent a higher grade of neuroendocrine tumor and thus require more aggressive treatment. In line with the WHO guidelines, neuroendocrine tumors should be graded as per other gastrointestinal tumors; the American Joint Committee on Cancer published a tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification staging system for carcinoids in 2010 with the aim of providing a uniform means of reporting stage [8]. This will aid in future research and guidelines/protocols on management and treatment.

In terms of treatment modalities, endoscopic treatment was by far the most commonly used, in 78 % of all cases. This is probably partly the result of the improved quality of and increased access to endoscopic instruments. With advances in endoscopic diagnosis of disease have come new treatment modalities, such as EMR, ESD, and ESMR-L. There are limited data on the superiority of these endoscopic treatments, but a small meta-analysis and some articles published do favor ESMR-L and ESD over EMR with higher clear resection margins for small tumors (<10 mm) [13, 20]. The recent meta-analysis by Zhong et al. [13] concluded that tumors up to 16 mm operated with ESD had low recurrence rates and comparable complication rates with EMR. It has been previously published that tumors greater than 20 mm should have radical surgery [33], and currently the literature regarding endoscopic treatment of rectal carcinoids does not detail any attempts in tumors larger than this size [13, 18–20].

In this series, local surgical excision accounted for the treatment of 10 % of cases and radical surgery 12.6 %. The data, with regard to the type of radical surgery, were poorly reported in the articles from this review. There was large variability in rates of radical surgery from 4–50 % [12, 21–26]. It will be interesting to see whether there is a trend toward more radical surgery or whether the popularity and advancements in endoscopy will lead to radical surgery being reserved as a salvage operation where there is poor prognostic histopathology.

This article aimed to review the recent literature with regards to rectal carcinoids, detailing the management and treatment of over 4,000 patients. As with any publication of this nature, analyzing data from multiple international sources over a 20-year span will introduce error. There was wide variation in the data recorded from the various sources, so it was not possible to analyze all 4,575 patients for each parameter, and it was inappropriate to perform a meta-analysis. This systematic review has, however, corroborated previously published data in small and large series. The introduction of the TNM classification for rectal carcinoids will help homogenize the classification of tumors across the globe so we can compare like with like.

In light of the findings of this systematic review, we suggest that small rectal carcinoids up to 10 mm without adverse features can be treated with local/endoscopic excision. The treatment of carcinoids between 10 and 20 mm is still contentious, but those up to 16 mm without adverse features are suitable for local/endoscopic excision followed by careful histopathological assessment. Patients with tumors greater than 16 mm or any size with adverse features should have radical surgery in view of the high lymph node metastasis rate in this subtype of tumor. Rectal carcinoid tumors need to be respected, and as such, they should be treated in a center that can provide a multidisciplinary approach with appropriate expertise in neuroendocrine tumors.

References

Langhans T (1867) Ueber einen drusenpolyp im ileum. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med 38:559–560

Lubarsch O (1888) Uber den primaren Krebs des ileum nebst Bemerkungen uber das gleichzeitige Vorkommen von Krebs and Tuberkulose. Virchows Arch 3:280–317

Oberndorfer S (1907) Karzinoide tumoren des dunndarms. Frankf Z Pathol 1:426–432

Anthony LB, Strosberg JR, Klimstra DS et al (2010) The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (NETS): well-differentiated nets of the distal colon and rectum. Pancreas 39:767–774

Soga J (1997) Carcinoids of the rectum: an evaluation of 1271 reported cases. Surg Today 27:112–119

Scherubl H (2009) Rectal carcinoids are on the rise: early detection by screening endoscopy. Endoscopy 41:162–165

Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M (2003) A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 97:934–959

Edge SB, Compton CC (2010) The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 17:1471–1474

Downs SH, Black N (1998) The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Commun Health 52:377–384

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Maggard MA, O’Connell JB, Ko CY (2004) Updated population-based review of carcinoid tumors. Ann Surg 240:117–122

Kim MS, Hur H, Min BS et al (2013) Clinical outcomes for rectal carcinoid tumors according to a new (AJCC 7th edition) TNM staging system: a single institutional analysis of 122 patients. J Surg Oncol 107:835–841

Zhong DD, Shao LM, Cai JT (2013) Endoscopic mucosal resection vs endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 15:283–291

Lee DS, Jeon SW, Park SY et al (2010) The feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumors: comparison with endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy 42:647–651

Onozato Y, Kakizaki S, Iizuka H et al (2010) Endoscopic treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Dis Colon Rectum 53:169–176

Park HW, Byeon JS, Park YS et al (2010) Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 72:143–149

Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Qin XY et al (2010) Advantages of endoscopic submucosal dissection with needle-knife over endoscopic mucosal resection for small rectal carcinoid tumors: a retrospective study. Surg Endosc 24:2607–2612

Son HJ, Sohn DK, Hong CW et al (2013) Factors associated with complete local excision of small rectal carcinoid tumor. Int J Colorectal Dis 28:57–61

Kim HH, Park SJ, Lee SH et al (2012) Efficacy of endoscopic submucosal resection with a ligation device for removing small rectal carcinoid tumor compared with endoscopic mucosal resection: analysis of 100 cases. Dig Endosc 24:159–163

Kim KM, Eo SJ, Shim SG et al (2013) Treatment outcomes according to endoscopic treatment modalities for rectal carcinoid tumors. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. doi:10.1016/j.clinre.2012.07.007

Kasuga A, Chino A, Uragami N et al (2012) Treatment strategy for rectal carcinoids: a clinicopathological analysis of 229 cases at a single cancer institution. J Gastroenterol Hepat 27:1801–1807

Colonoscopy Study Group of Korean Society of C (2011) Clinical characteristics of colorectal carcinoid tumors. J Korean Soc Coloproctol 27:17–20

Shields CJ, Tiret E, Winter DC et al (2010) Carcinoid tumors of the rectum: a multi-institutional international collaboration. Ann Surg 252:750–755

Yoon SN, Yu CS, Shin US et al (2010) Clinicopathological characteristics of rectal carcinoids. Int J Colorectal Dis 25:1087–1092

Wang M, Peng J, Yang W et al (2011) Prognostic analysis for carcinoid tumours of the rectum: a single institutional analysis of 106 patients. Colorectal Dis 13:150–153

Kim BN, Sohn DK, Hong CW et al (2008) Atypical endoscopic features can be associated with metastasis in rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc 22:1992–1996

Li AF, Hsu CY, Li A et al (2008) A 35-year retrospective study of carcinoid tumors in Taiwan: differences in distribution with a high probability of associated second primary malignancies. Cancer 112:274–283

Soga J (2005) Early-stage carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 1914 reported cases. Cancer 103:1587–1595

Modlin IM, Oberg K, Chung DC et al (2008) Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol 9:61–72

Kobayashi K, Katsumata T, Yoshizawa S et al (2005) Indications of endoscopic polypectomy for rectal carcinoid tumors and clinical usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography. Dis Colon Rectum 48:285–291

Ramage JK, Davies AH, Ardill J et al (2005) UKNETwork for Neuroendocrine Tumours Guidelines for the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine (including carcinoid) tumours. Gut 54(suppl 4):1–16

Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT, Capella C, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, Komminoth P, Solcia E (2010) Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND (eds) Who classification of tumours of the digestive system, 4th edn. IARC, Lyon, pp 13–14

Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I et al (2005) Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology 128:1717–1751

Disclosures

Mr. McDermott, Miss Heeney, Dr. Courtney, Miss Mohan, and Professor Winter have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDermott, F.D., Heeney, A., Courtney, D. et al. Rectal carcinoids: a systematic review. Surg Endosc 28, 2020–2026 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3430-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3430-0