Abstract

Background

Adequate working space is a prerequisite for safe and efficient minimal access surgery. No objective data exist in literature about the effect of mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) on working space in laparoscopic surgery. We objectively measured this effect with computed tomography in a porcine laparoscopy model.

Methods

Using standardized anesthesia, twelve 20-kg pigs without MBP and eight 20-kg pigs with MBP were studied with computed tomography at intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) levels of 0, 5, 10, and 15 mmHg. Volumes and dimensions of the pneumoperitoneum were measured on reconstructed CT images and compared between the pigs with and those without MBP.

Results

A reproducible and statistically significant increase of approximately 500 ml in pneumoperitoneum volume was found in the MBP group at all levels of IAP. This represents a 43 % relative increase at a pneumoperitoneum pressure of 5 mmHg, 21 % at IAP 10 mmHg, and 18 % at IAP 15 mmHg. Peak inspiratory pressure was lower at IAP 0 and 5 mmHg in the MBP group. Anteroposterior diameter in the group with MBP was lower at 0 mmHg, but abdominal dimensions were similar in both groups at all other IAPs. This shows that the gain in working space is due to a diminished volume of the intra-abdominal content and not to compression or displacement of the bowel.

Conclusions

MBP increases working space by reducing bowel content. Especially at low intra-abdominal working pressures, the increase in working space associated with MBP could represent an important benefit in challenging laparoscopic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The introduction of laparoscopic procedures has led to important progress in colorectal surgery. Short-term results have been shown to be superior, including less postoperative pain, earlier recovery of bowel function, less blood loss, and shorter hospital stay [1–4]. Long-term results, defined as disease-free survival, do not differ between patients operated on by means of laparotomy or laparoscopy [1, 3]. However, despite the short-term advantages, laparoscopy also has negative aspects. It has a longer learning curve [5], increases operating times and costs [2, 3], and it has the disadvantages of a CO2 pneumoperitoneum [6–18]. Various solutions have been proposed to overcome the consequences of CO2 pneumoperitoneum [19–24]. Nevertheless, obtaining enough working space is essential for good view and handling of instruments [25–27].

Several factors influence working space, e.g., age and size of the patient, obesity, bowel content, pneumoperitoneum-pressure, positioning of the patient, use of systemic neuromuscular blocking agents, and ventilation settings [28]. Whether preoperative mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) influences working space has not been established [29, 30]. However, several, randomized, controlled trials and meta-analyses have been conducted on MBP before colorectal operations to investigate its influence on anastomotic leakage and septic complications. The vast majority of studies conclude that there is no advantage of MBP before colorectal resections regarding the aforementioned complications [31–38]. The purpose of this study was to investigate in a porcine model whether MBP has a positive influence on working space during laparoscopy.

Methods

Animals

Twenty female Landrace pigs, weighing approximately 20 kg, were studied: 8 pigs received MBP, whereas 12 pigs did not. The study was approved by the institutional animal ethics committee.

Mechanical bowel preparation

In the MBP group, food was withheld and replaced by water ad libitum and sweetened water at 30 h before the experiment. Animals were placed in cages without floor coverage. At 24 and 8 h before surgery, 20 ml of sodium phosphate was administered orally, followed by 100 ml of water. Pigs in the non-MBP group were fed ad libitum until premedication.

Anesthesia

All pigs were subjected to the same anesthesia protocol as described earlier by the authors [28]. After premedication with midazolam and ketamine in the animal housing facility, animals were brought to the laboratory and intubated. Maintenance anesthesia consisted of sufentanil and propofol. No neuromuscular blocking agents were used for these experiments. Artificial ventilation was volume-controlled (10 ml/kg), with a positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) set at 5 cm H2O. Only the respirator frequency was adjusted when End-Tidal CO2 (ETCO2) rose above 7 kPa. Arterial and venous access was established. Heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, peak inspiratory pressure (PIP), and ETCO2 were measured continuously. A 5-mm radially expanding trocar (Versastep®, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) was placed in the supraumbilical midline. The correct intra-abdominal position was verified endoscopically (Storz Telepack®, Tuttlingen, Germany, 5-mm 30° telescope).

Study protocol

With stable cardiorespiratory parameters, the pig was transported to the CT scanner (Somatom Definition Flash Dual Source®, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). After installation of the pig on the scanning tray, an electronic CO2 insufflator (Endoflator®, Storz) was attached to the abdominal trocar. Breath-hold end-expiratory computed tomography (CT) of thorax and abdomen, lasting ca. 5 seconds, was performed at intra-abdominal pressures (IAP) of 0, 5, 10, and 15 mmHg. At each pressure level, a stabilization period of 5 minutes was taken into account and cardiorespiratory parameters were documented. After finishing the scans, the pig was euthanized.

Outcome measurements

Body weight as well as the total length of the first five lumbar vertebral bodies in a sagittal CT midline plane was measured. This CT length was measured to get an objective measure for the size of the pig, not dependent on food status like the weight [39]. All pigs had six lumbar vertebrae, but the physiologic lordosis made measuring of the length of the first five lumbar vertebrae easiest and most reproducible.

Intra-abdominal volume of pneumoperitoneum was calculated with the Syngo 3D volume-module of a Siemens Navigator® workstation using a dataset of 5-mm slices. With the definition of appropriate thresholds, semiautomatic detection of CO2 in the abdomen was done on transverse slices [40]. These could be integrated to a total volume of pneumoperitoneum. All volumes were visually checked for inadvertent inclusion of air in the bowel (Fig. 1a, b).

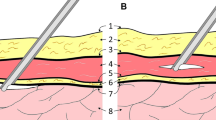

A Reconstructed sagittal CT-image at an intra abdominal pressure of 5 mmHg. Measured are the maximum abdominal external antero-posterior (AP) diameter in a sagittal midline plane and the maximum distance between the upper border of the pubic symphysis and the highest diaphragmatic peritoneal lining. B Reconstructed coronal CT-image at an intra abdominal pressure of 5 mm Hg. Measured is the maximum abdominal external transverse diameter in a transverse and coronal plane. (Source: Reproduced with permission from Surgical Endoscopy)

In a sagittal midline plane, maximum external anteroposterior diameter of the abdomen and maximum distance between the upper border of the pubic symphysis and the highest diaphragmatic peritoneal lining was measured on CT images at all levels of IAP. In a coronal plane, the maximum external transverse diameter was measured (Fig. 1a, b).

Statistics

Normality of the data was confirmed by means of visual assessment and Kolmogorov Smirnov testing. Data are presented as means with standard errors of the mean. Differences between groups were assessed by using an independent samples t test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

One pig in the non-MBP group died during surgical preparation, leaving the data of 19 pigs eligible for analysis. There was no statistically significant difference in body weight or in length of the first five lumbar vertebrae between the non-MBP and the MBP group, but mean body weight was 1.2 kg lower in the MBP group (Table 1). Cardiorespiratory parameters are shown in Table 2. Changes in respiratory rate to compensate for hypercapnia were made in three pigs in the non-MBP group (average increase 10 breaths/min) and five pigs in the MBP group (average increase 14 breaths/min). PIP was significantly lower in the MBP group at IAP of 0 and 5 mmHg. This reduction in PIP disappeared at IAPs of 10 and 15 mmHg.

When comparing the CT pneumoperitoneum volumes at different IAPs between groups, pigs in the MBP group had a significantly higher pneumoperitoneum volume, gaining approximately 500 ml at each IAP level (Table 3). The relative increase associated with MBP was 43 % at IAP 5 mmHg, 21 % at 10 mmHg, and 18 % at 15 mmHg. The pneumoperitoneum volume attained at IAP 10 mmHg with MBP was similar to the volume at IAP 15 mmHg without MBP.

The dimensions of the abdomen are presented in Table 4. As can be seen, a difference in anteroposterior diameter of the abdomen exists between the non-MBP and MBP group only in the noninsufflated state. There were no significant differences in transverse diameter or symphysis-to-diaphragm distance of the abdomen between the non-MBP and MBP group.

Discussion

The standard use of MBP has been largely abandoned, because studies have proven that its use does not diminish the risk of anastomotic leakage or wound infections [31–38]. However, the relationship between MBP and working space in laparoscopic surgery is still a matter of debate. The two level 1A studies on MBP in open colorectal surgery have contradictory discussions on the theoretical influence of MBP in laparoscopy. It has been argued that it is easier to perform laparoscopic surgery if the bowel contains solid matter to use gravity to obtain better overview [35] or that MBP results in dilated bowel, which could hamper laparoscopic vision and make mobilization of the intestines more difficult [37].

Only a few studies have evaluated the effect of MBP on exposure in gynecologic laparoscopy. In the first study, performed by Muzii et al. [29], patients were randomized between preoperative MBP (sodium phosphate) and no MBP; the endpoint was the appropriateness of the surgical field as judged by the surgeon on a scale going from poor to excellent in five steps. No advantage of MBP on the evaluation of the surgical field could be demonstrated. Another randomized trial, performed by Yang et al. [30], divided patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopy in two groups. The first group received MBP through oral sodium phosphate solution; the second group received only a sodium phosphate enema. Assessment of the quality of the surgical field and bowel characteristics was performed by using a surgeon questionnaire with Likert and visual analog scales. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in evaluation of the surgical field, bowel handling, degree of bowel preparation, or surgical difficulty.

Two additional surveys (laparoscopic colon and rectum surgery, and laparoscopic gynaecology) show MBP is still used for different reasons in these fields of laparoscopy [41, 42]. One of these reasons is the possible influence MBP could have on surgical field exposure.

All of these studies reflect individual preferences rather than evidence based practice. Moreover, the surgeon’s evaluation of the working space may be too subjective to detect significant differences in outcome.

For this reason, we conducted this animal study to investigate whether MBP has an influence on laparoscopic working space. The results show a significant increase in pneumoperitoneum volume in the group receiving MBP preoperatively. This gain in pneumoperitoneum volume of 500 ml CO2 is independent of the pressure of pneumoperitoneum and represents a relative increase of 43 % at 5 mmHg and 21 % at 10 mmHg and 18 % at 15 mmHg. Consequently, with preoperative MBP the same volume of pneumoperitoneum can be obtained at lower IAPs (Table 3).

Concordantly, mechanical ventilation is easier in MBP pigs at low pneumoperitoneum pressures (diminished PIP at 0 and 5 mmHg in the MBP group; Table 2). Anteroposterior diameter in the group with MBP was lower at 0 mmHg, but abdominal dimensions were similar in both groups at all other IAPs. This shows that the gain in working space is due to a diminished volume of the intra-abdominal content and not to compression or displacement of the bowel (Table 4).

In this animal study, our choice for MBP was sodium phosphate. The most commonly prescribed preparations for bowel cleaning in humans are sodium phosphate (90 ml), poly-ethylene glycol (PEG, 4 l), and magnesium citrate (300 ml). Literature shows sodium phosphate has the highest patient compliance and least residual stool [43–45]. In animals, orogastric intubation is required to administer large volumes of lavage solution over several minutes, leading to discomfort, struggling, and apparent increased stress [46]. Sodium phosphate is a low-volume, hyperosmolar, buffered saline laxative that osmotically draws water into the gastrointestinal tract lumen. It relies on osmotic action to draw plasma water into the colon to soften and flush fecal material out of the colon [44, 45]. Its use for MBP in pigs before colonoscopy has been shown by Pfeffer et al. [47].

A difference between the two groups of pigs, except for MBP, is the duration of fasting. Food was withheld from pigs receiving MBP beginning the day before the experiment. Whether this also influences the volume of intra-abdominal content or might have caused the 1.2 kg difference in mean body weight has not been investigated in this study. This raises the question of the necessity of MBP. In a blinded, randomized, controlled trial in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery for benign disease, a 7-day low-fiber diet gave as good exposure as PEG (scored by the surgeon) but was far better tolerated [48].

Conclusions

MBP before laparoscopy in pigs results in an increased volume of CO2 pneumoperitoneum irrespective of IAP. This could represent an important benefit in technically challenging intestinal and nonintestinal laparoscopic surgery. The relative gain in volume of CO2 pneumoperitoneum by MBP is highest at lower insufflation pressures, which can be helpful in low-pressure laparoscopic surgery, as is custom in pediatric surgery. Further studies are necessary to investigate whether a similar effect could be obtained with more patient-friendly bowel preparations, such as low-fiber diet.

References

Nelson H, Sargent DJ, COST Study Group (2004) A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350(20):2050–2059

Breukink S, Pierie J, Wiggers T (2006) Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD005200

Reza MM et al (2006) Systematic review of laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 93(8):921–928

Veldkamp R et al (2005) Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 6(7):477–484

Schlachta CM et al (2001) Defining a learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal resections. Dis Colon Rectum 44(2):217–222

Blobner M et al (1998) Effects of intra-abdominally insufflated carbon dioxide and elevated intraabdominal pressure on splanchnic circulation: an experimental study in pigs. Anesthesiology 89(2):475–482

Burgos FJ et al (2009) Changes in visceral flow induced by laparoscopic and open living-donor nephrectomy: experimental model. Transplant Proc 41(6):2491–2492

Caldwell CB, Ricotta JJ (1987) Changes in visceral blood flow with elevated intraabdominal pressure. J Surg Res 43(1):14–20

Gupta A, Watson DI (2001) Effect of laparoscopy on immune function. Br J Surg 88(10):1296–1306

Hirvonen EA et al (2000) The adverse hemodynamic effects of anesthesia, head-up tilt, and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 14(3):272–277

Jakimowicz J, Stultiens G, Smulders F (1998) Laparoscopic insufflation of the abdomen reduces portal venous flow. Surg Endosc 12(2):129–132

Koivusalo AM, Lindgren L (1999) Respiratory mechanics during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg 89(3):800

Neudecker J et al (2002) The European Association for Endoscopic Surgery clinical practice guideline on the pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 16(7):1121–1143

Sammour T et al (2009) Systematic review of oxidative stress associated with pneumoperitoneum. Br J Surg 96(8):836–850

Schilling MK et al (1997) Splanchnic microcirculatory changes during CO2 laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg 184(4):378–382

Yasir M et al (2012) Evaluation of post operative shoulder tip pain in low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgeon 10(2):71–74

Reintam Blaser A, Bloechlinger S (2010) Should we be worried about disturbed sympathovagal balance during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Minerva Anestesiol 76(11):876–878

Ure BM et al (2007) Physiological responses to endoscopic surgery in children. Semin Pediatr Surg 16(4):217–223

Balick-Weber CC et al (2007) Respiratory and haemodynamic effects of volume-controlled vs pressure-controlled ventilation during laparoscopy: a cross-over study with echocardiographic assessment. Br J Anaesth 99(3):429–435

Chassard D et al (1996) The effects of neuromuscular block on peak airway pressure and abdominal elastance during pneumoperitoneum. Anesth Analg 82(3):525–527

Dexter SP et al (1999) Hemodynamic consequences of high- and low-pressure capnoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 13(4):376–381

Gurusamy KS, Samraj K, Davidson BR (2008) Abdominal lift for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD006574

Gurusamy KS, Samraj K, Davidson BR (2009) Low-pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD006930

Wong YT et al (2005) Peritoneal pH during laparoscopy is dependent on ambient gas environment: helium and nitrous oxide do not cause peritoneal acidosis. Surg Endosc 19(1):60–64

Emam TA et al (2000) Effect of intracorporeal-extracorporeal instrument length ratio on endoscopic task performance and surgeon movements. Arch Surg 135(1):62–65 discussion 66

Frede T et al (1999) Geometry of laparoscopic suturing and knotting techniques. J Endourol 13(3):191–198

Hanna GB, Shimi S, Cuschieri A (1997) Influence of direction of view, target-to-endoscope distance and manipulation angle on endoscopic knot tying. Br J Surg 84(10):1460–1464

Vlot J, Wijnen R, Stolker RJ, Bax K (2012) Optimizing working-space in porcine laparoscopy: CT measurement of the effects of intra-abdominal pressure. Surg Endosc Dec 13 [Epub ahead of print]

Muzii L et al (2003) Bowel preparation for gynecological surgery. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 48(3):311–315

Yang LC et al (2011) Mechanical bowel preparation for gynecologic laparoscopy: a prospective randomized trial of oral sodium phosphate solution vs single sodium phosphate enema. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 18(2):149–156

Bretagnol F et al (2007) Rectal cancer surgery without mechanical bowel preparation. Br J Surg 94(10):1266–1271

Bucher P et al (2005) Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation before elective left-sided colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 92(4):409–414

Contant CM et al (2007) Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 370(9605):2112–2117

Fa-Si-Oen P et al (2005) Mechanical bowel preparation or not? Outcome of a multicenter, randomized trial in elective open colon surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 48(8):1509–1516

Guenaga KK, Matos D, Wille-Jorgensen P (2009) Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD001544

Jung B et al (2007) Multicentre randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colonic resection. Br J Surg 94(6):689–695

Slim K et al (2004) Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of colorectal surgery with or without mechanical bowel preparation. Br J Surg 91(9):1125–1130

Zmora O et al (2006) Laparoscopic colectomy without mechanical bowel preparation. Int J Colorectal Dis 21(7):683–687

King JWB, Roberts RC (1960) Carcass length in the bacon pig; its association with vertebrae numbers and prediction from radiographs of the young pig. Animal Prod 2(1):59–65

Cai W et al (2009) MDCT for automated detection and measurement of pneumothoraces in trauma patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 192(3):830–836

Slieker JC et al (2011) Bowel preparation prior to laparoscopic colorectal resection: what is the current practice? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 21(10):899–903

Wells T, Plante M, McAlpine JN (2011) Preoperative bowel preparation in gynecologic oncology: a review of practice patterns and an impetus to change. Int J Gynecol Cancer 21(6):1135–1142

Hara AK et al (2011) National CT colonography trial (ACRIN 6664): comparison of three full-laxative bowel preparations in more than 2500 average-risk patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 196(5):1076–1082

Hsu CW, Imperiale TF (1998) Meta-analysis and cost comparison of polyethylene glycol lavage versus sodium phosphate for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc 48(3):276–282

Law WL et al (2004) Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial comparing polyethylene glycol solution, one dose and two doses of oral sodium phosphate solution. Asian J Surg 27(2):120–124

Daugherty MA et al (2008) Safety and efficacy of oral low-volume sodium phosphate bowel preparation for colonoscopy in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 22(1):31–36

Pfeffer J et al (2006) The Aer-O-Scope: proof of the concept of a pneumatic, skill-independent, self-propelling, self-navigating colonoscope in a pig model. Endoscopy 38(2):144–148

Lijoi D et al (2009) Bowel preparation before laparoscopic gynaecological surgery in benign conditions using a 1-week low fibre diet: a surgeon blind, randomized and controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 280(5):713–718

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P. Specht for assistance in the experiments and M. Dijkshoorn for CT scanning.

Disclosures

John Vlot, Juliette Slieker, René Wijnen, Johan Lange, and Klaas Bax have no conflict of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

John Vlot and Juliette C. Slieker contributed equally.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vlot, J., Slieker, J.C., Wijnen, R. et al. Optimizing working-space in laparoscopy: measuring the effect of mechanical bowel preparation in a porcine model. Surg Endosc 27, 1980–1985 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2697-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2697-2