Abstract

Background

Rectovaginal fistulas (RVFs) are a rare surgical condition. Their treatment is extremely difficult, and no standard surgical technique is accepted worldwide. This report describes a new approach using transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) to treat RVFs.

Methods

A retrospective review of 13 patients who underwent repair of rectovaginal fistula using TEM between 2001 and 2008 was undertaken. The surgical technique is widely described, and the advantages of the endorectal approach are noted.

Results

The median follow-up period was 25 months, and the median age of the patients was 44 years (range, 25–70 years). The mean operative time was 130 min (range, 90–150 min), and the hospital stay was 5 days (range, 3–8 days). One patient experienced recurrence. This patient underwent reoperation with TEM and experienced re-recurrence. Two patients had minor complications (hematoma of the septum and abscess of the septum), which were treated with medical therapy. For two patients, a moderate sphincter hypotonia was registered.

Conclusions

A new technique for treating RVFs using TEM is presented. The authors strongly recommend this approach that avoids any incision of the perineal area, which is very painful and can damage sphincter functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rectovaginal fistulas (RVFs) represent a difficult condition and probably are the most distressing surgical condition physically, psychologically, and socially that women can experience. Women with this condition can feel ashamed and isolated. Obstetric injury is the most common cause. Other more frequent causes are cryptoglandular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic radiotherapy, and colorectal surgery related to partial healing of colorectal anastomosis or previous abscess. Spontaneous healing is extremely rare. Such healing also rarely occurs after stoma.

Treatment of RVF generally is considered to be extremely difficult, and various techniques have been advocated. Primary repair of the fistula has a success rate of 70–97%, but after one or more unsuccessful attempts at repair, the success rate falls to 40–85% [1]. Various surgical and nonsurgical methods of repair are used, and a gold standard procedure still is to be determined. The surgical approaches reported for the treatment of high RVF are transanal, transvaginal, perineal, transabdominal, and laparoscopic techniques of repair [2]. The rectal mucosal advancement flap repair is the most popular procedure, with success rates ranging from 60–80%. The nonsurgical approaches are fistulography and application of fibrin glue.

This report aims to describe a new approach that we developed using transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) to remove the fistula and the surrounding scar tissue.

Materials and methods

From February 2001 to December 2008, we treated 13 patients (median age, 44 years; range, 25–70 years) with rectovaginal fistulas. In nine cases, RVFs were first treated elsewhere with transperineal direct suture of the rectal and vaginal walls, and four patients had two or three previous attempts at surgical repair with the transabdominal or transperineal approach or both and direct suture. All the patients had a diverting stoma at the first referral. Fistulas occurred as a consequence of transvaginal hysterectomy (n = 7), low anterior mechanical resection (n = 5), and postradiotherapy (n = 1).

The preoperative algorithm for all the patients included colonoscopy, X-ray clisma, endorectal ultrasonography, anorectal manometry, computed tomography (CT), or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). The preoperative preparation consisted of a standard mechanical bowel irrigation, an antibiotic, and thrombotic prophylaxis. The medium distance of the RVFs from the anal verge was 7 cm (range, 4–10 cm).

The use of TEM follows the same principles as traditional surgery, with the well-known advantages related to magnification of the view and excellent lightning. The patient is placed in prone position on the operating table. The operation has four steps:

-

Step 1. Once the Buess rectoscope is introduced, the fistula is clearly identified with a Nelaton tube introduced through the vagina or with the use of methylene blue. The vagina then is packed with gauze to avoid or reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) leakage (Fig. 1).

-

Step 2. Under three-dimensional TEM direct vision, the fistula sclerotic tissue is widely excised. The margin of the excisional line must be normal tissue. A conservative approach runs the risk of not including all the scar tissue and can lead to unsuccessful outcomes. The dissection in the rectovaginal septum laterally and aborally to the fistula is easily performed with TEM instrumentation. When dissection of the septum is completed, the TEM instrumentation is temporarily removed.

-

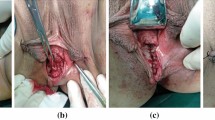

Step 3. Introducing the finger into the dissected area of the septum, the surgeon blindly completes dissection of the aboral part of the septum until the sphincter fibers are reached (the oral part of the septum has been previously managed with TEM). This part of the operation cannot be performed using TEM instrumentation for technical reasons. The dissection of this part of the septum is easy once the correct plane is identified and has no risk of bleeding (Fig. 2).

-

Step 4. The Buess’ rectoscope is introduced again, and suture of the vagina edge is performed with three or four stitches to obtain a longitudinal suture. The stitch extremities are left in the vagina to be tied at the end of the operation. The hemostasis is carefully verified, and a transverse suture line is performed on the rectal wall. The patient is placed in supine position, and a vaginal retractor is placed. After this, the vagina is sutured to have introflected edges (Fig. 3).

Results

All the patients were referred with a diverting stoma. They were able to ambulate on the first postoperative day after TEM. Free oral intake was achieved on the second day. The mean operative time was 130 min (range, 90–150 min), and the hospital stay was 5 days (range, 3–8 days). Analgesics were used only on the first postoperative day. The patients were able to resume work on postoperative day 10.

Radiologic evaluation performed on postoperative day 10 showed no fistulas. In two cases, the procedure was complicated by hematoma of the septum and abscess of the septum treated with antibiotic therapy. In two cases, we observed nightly soiling, and an anorectal manometry showed a moderate sphincter hypotonia. This functional sequela was resolved in 3 months with sphincter re-education.

The median follow-up period was 25 months, with evidence of one recurrence (7%), which occurred within 30 days after TEM. The patient had undergone a previous low anterior resection for T3 N1 rectal cancer after neoadjuvant treatment. The recurrent RVF was treated again with TEM, and a re-recurrence was observed after 40 days. Up to this writing, the patient has maintained her ostomy because she has refused any other surgical treatment.

Discussion

Rectovaginal fistulas constitute fewer than 5% of all anorectal fistulas [3]. Obstetric injury is the most common cause, occurring in up to 70–88% of cases [2, 4]. Other causes include rectal anterior resections (0.9–2.9%) [2] or vaginal surgery, perianal or Bartholin’s gland infection, radiation proctitis, and inflammatory bowel disease [3]. The fistula also may occur as a complication of leukemia or other malignancies.

Many techniques have been developed in the attempt to treat RVFs. In the early 1980s, the endorectal advancement flap (EAF) was advocated as the treatment of choice for patients with low rectovaginal fistulas. Initially, the reported results were very promising, with the healing rate varying between 78 and 95%. More recently, however, a significantly low healing rate has been reported, especially for women who had previous repair [5]. In a retrospective review of 105 patients from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation who underwent EAF, 37 had rectovaginal fistulas, and 21 patients (56.8%) experienced recurrences. Thus, the primary rate of healing was 43.2%. The authors concluded that “although the EAF continues to be successfully used to treat rectovaginal fistulas, it seems as though our success rate was not as optimistic as some of the other published studies, and has not shown improvement over the past five years” [6].

In the early 1990s, it was suggested that interposition of healthy, well-vascularized tissue may be the key to rectovaginal fistula healing. Multiple surgical strategies for transferring healthy nonirradiated tissue have been described. These methods involve the use of skin flaps, muscle flaps, musculocutaneous flaps, intestinal flaps, and the Martius flap, including subcutaneous tissue and bulbocavernosus muscle from one of the labia minora [7–19, 20]. The beneficial effect of a puborectal sling interposition has been reported, with a high success rate varying between 92 and 100%. In 2006, Oom et al. [5], reporting on series of 26 consecutive patients, noted that the rectovaginal fistulas healed for 16 of the patients (62%). For the patients who had undergone one or more previous repairs, the healing rate was only 31% compared with 92% for the patients without previous repairs.

Wexner et al. [21, 22] in 2008 used the technique of graciloplasty in performing RVFs for a group of 15 patients. This method led to a success rate of 75% (range, 60–100%), determined by negative prognostic factors such as inflammatory bowel disease and radiation.

Several other methods of treatment for RVF have been used including fibrin sealant instillation, ileal pouch mucosal advancement flap or circumferential pouch advancement, and a proctectomy with colonic pull-through and delayed coloanal anastomosis.

Buess originally developed TEM in 1983. Actually, this technique is used for the treatment of rectal adenomas and cancer (T1-T2).

To our knowledge, no series of TEM repair of rectovaginal fistulas has been reported in literature. Only three case reports by Vàvra [23, 24] and Darwood and Borley [25] have been published.

The main advantage offered by TEM as an alternative to the flap technique is the use of an endoluminal approach, which eliminates the need of a perineal incision, in contrast to other more invasive techniques. Furthermore, the magnification and three-dimensional view allow for a precise identification of the vaginal and rectal surfaces by removal of the sclerotic tissue. Consequently, the suture can be performed on healthy tissue, which guarantees total control of the hemostasis by magnification of the direct vision. It also is necessary that each of these sutures be performed on different planes, longitudinal and transversal.

Often, RVF is associated with lumen stenosis, especially after surgery–radiotherapy. This may pose an objective difficulty for the performance of TEM. In the current series, however, RVF was never associated with lumen stenosis.

The main drawback of the reported technique is that its vision method does not allow for distal dissection of the rectum. Instead, this dissection must be performed manually and blindly before identification of the avascular plane.

Complying with such criteria ensures a high recovery/healing rate (93%), higher than with other techniques. The complication rate was 15%. However, the complications were minor, resolving promptly with antibiotic therapy.

In two cases, we observed nightly soiling due to the TEM-caused sphincter trauma related to the patients’ age and the preoperative sphincter function. This problem was resolved within 3 months thanks to sphincter re-education. Only in one case did we observe a relapse, which after treatment with TEM resulted in another relapse. The patient experienced a rectal carcinoma and was submitted to radiochemotherapy. We believe that such failure is mainly due to a sclerotic process of the tissues (rectum and vagina), with inadequate revascularization. To obtain positive results, a long learning curve for the TEM technique with extended experience in local excision of polyps seems to be vital. Hence, we advocate that such treatment be performed exclusively in highly specialized centers.

Conclusion

We present a new technique for treating RVFs with TEM. We strongly recommend this approach that avoids any incision in the perineal area, which is very painful and can damage sphincter functions.

References

Kosugi C, Saito N, Kimata Y, Ono M, Sugito M, Ito M, Sato K, Koda K, Miyazaki M (2005) Rectovaginal fistulas after rectal cancer surgery: incidence and operative repair by gluteal-fold flap repair. Surgery 137:329–336

Kumaran SS, Palanivelu C, Kavalakat AJ, Parthasarathi R, Neelayathatchi M (2005) Laparoscopic repair of high rectovaginal fistula: is it technically feasible? BMC Surg 5:20

Walfisch A, Zilberstein T, Walfisch S (2004) Rectovaginal septal repair: case presentations and introduction of a modified reconstruction technique. Tech Coloproctol 8:192–194

Chitrathara K, Namratha D, Francis V, Gangadharan VP (2001) Spontaneous rectovaginal fistula and repair using bulbocavernosus muscle flap. Tech Coloproctol 5:47–49

Oom DM, Gosselink MP, Van Dijl VR, Zimmerman DD, Schouten WR (2006) Puborectal sling interposition for the treatment of rectovaginal fistulas. Tech Coloproctol 10:125–130 (discussion 130, Epub 19 June 2006)

Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR, Fazio VW (2002) Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1622–1628

McCraw JB, Massey FM, Shankilin KD, Horton CE (1976) Vaginal reconstruction with gracilis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 58:176

Cardon A, Pattyn P, Monstrey S, Hesse U, de Hemptinne B (1999) Use of a unilateral pudendal thigh flap in the treatment of complex rectovaginal fistula. Br J Surg 86:645–646

Gurlek A, Gherardini G, Coban YK, Gorgu M, Erdogan B, Evans GR (1997) The repair of multiple rectovaginal fistulas with the neurovascular pudendal thigh flap (Singapore flap). Plast Reconstr Surg 99:2071–2073

Wee JT, Joseph VT (1989) A new technique of vaginal reconstruction using neurovascular pudendal thigh flaps: a preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg 83:701

Monstrey S, Blondeel P, Van Landuyt K, Verpaele A, Tonnard P, Matton G (2001) The versatility of the pudendal thigh fasciocutaneous flap used as an island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 107:719–725

Hagerty RC, Vaughn TR, Lutz MH (1988) The perineal artery axial flap in reconstruction of the vagina. Plast Reconstr Surg 82:344–345

Gleeson NC, Baile W, Roberts WS, Hoffman MS, Fiorica JV, Finan MA et al (1994) Pudendal thigh fasciocutaneous flaps for vaginal reconstruction in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol 54:269–274

Woods JE, Alter G, Meland B, Podratz K (1992) Experience with vaginal reconstruction utilizing the modified Singapore flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 90:270

Soper JT, Larson D, Hunter VJ, Berchuck A, Clarke-Pearson DL (1989) Short gracilis myocutaneous flaps for vulvovaginal reconstruction after radical pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 74:823

Tobin GR, Day TG (1988) Vaginal and pelvic reconstruction with distally based rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 81:62

Niazi ZB, Kogan SJ, Petro JA, Salzberg CA (1998) Abdominal composite flap for vaginal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 101:249

Cerna B, Rus J (1992) Repair of a vaginal defect with a musculocutaneous flap. Acta Chir Plast 34:38–43

Emirogiu M, Gultan SM, Adanali G, Apaydin I, Yormuk E (1996) Vaginal reconstruction with free jejunal flap. Ann Plast Surg 36:316–320

Pinedo G, Phillips R (1998) Labial fat pad grafts (modified Martius graft) in complex perianal fistulas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 80:410–412

Wexner SD, Ruiz DE, Genua J, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Zmora O (2008) Gracilis muscle interposition for the treatment of rectourethral, rectovaginal, and pouch-vaginal fistulas: results in 53 patients. Ann Surg 248:39–43

Ruiz D, Bashankaev B, Speranza J, Wexner SD (2008) Graciloplasty for rectourethral, rectovaginal, and rectovesical fistulas: technique overview, pitfalls, and complications. Tech Coloproctol 12:277–281 (discussion 281–282, Epub 5 August 2008)

Vávra P, Andel P, Dostalík J, Gunková P, Pelikán A, Gunka I, Martínek L, Vávrová M, Spurný P, Curík R, Koliba P (2006) The first case of management of the rectovaginal fistule using transanal endocsopic microsurgery. Rozhl Chir 85:82–85

Vàvra P, Dostalik J, Vavrova M, Gunkova P, Pai M, El-Gendi A, Habib N, Papaevangelou A (2009) Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a novel technique for the repair of benign rectovaginal fistula. Surgeon 7:126–127

Darwood RJ, Borley NR (2008) TEMS: an alternative method for the repair of benign rectovaginal fistulae. Colorectal Dis 10:619–620 (Epub 21 February 2008)

Disclosures

Giancarlo D’Ambrosio, Alessandro Paganini, Mario Guerrieri, Luciana Barchetti, Giovanni Lezoche, Emanuele Lezoche, and Bernardina Fabiani have no conflicts of interests or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D’Ambrosio, G., Paganini, A.M., Guerrieri, M. et al. Minimally invasive treatment of rectovaginal fistula. Surg Endosc 26, 546–550 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1917-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1917-5