Abstract

Background

This study aimed to describe the differences in the management of symptomatic gallstone disease within different elderly groups and to evaluate the association between older age and surgical treatment.

Methods

This single-institution retrospective chart review included all patients 65 years old and older with an initial hospital visit for symptomatic gallstone disease between 2004 and 2008. The patients were stratified into three age groups: group 1 (age, 65–74 years), group 2 (age, 75–84 years), and group 3 (age, ≥ 85 years). Patient characteristics and presentation at the initial hospital visit were described as well as the surgical and other nonoperative interventions occurring over a 1-year follow-up period. Logistic regression was performed to assess the effect of age on surgery.

Results

Data from 397 patient charts were assessed: 182 in group 1, 160 in group 2, and 55 in group 3. Cholecystitis was the most common diagnosis in groups 1 and 2, whereas cholangitis was the most common diagnosis in group 3. Elective admissions to a surgical ward were most common in group 1, whereas urgent admissions to a medical ward were most common in group 3. Elective surgery was performed at the first visit for 50.6% of group 1, for 25.6% of group 2, and for 12.7% of group 3, with a 1-year cumulative incidence of surgery of 87.4% in group 1, 63.5% in group 2, and 22.1% in group 3. Inversely, cholecystostomy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) were used more often in the older groups. Increased age (odds ratio [OR], 0.87; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84–0.91) and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.69–0.94) were significantly associated with a decreased probability of undergoing surgery within 1 year after the initial visit.

Conclusion

Even in the elderly population, older patients presented more frequently with severe disease and underwent more conservative treatment strategies. Older age was independently associated with a lower likelihood of surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The prevalence of gallstones among older persons varies from 20 to 30% and increases with age [1, 2], reaching 80% for institutionalized patients older than 90 years [3]. When symptomatic, disease usually is more severe in the elderly than in their younger counterparts [4–6]. Moreover, biliary disease represents the most common indication for abdominal surgery in the elderly [7].

The majority of studies examining gallstone disease in the elderly have focused almost solely on outcomes of interventions including endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) [4, 8, 9], percutaneous cholecystostomy [10–13] and, most often, surgery [14–18], generally for a more carefully selected group [19]. Only sparse reports exist on the management of elderly patients from the moment of presentation at the hospital with symptomatic biliary disease. More specifically, little is known about the severity of disease at initial presentation and how elderly patients are managed.

It is well documented that elderly patients are less likely to be treated than their younger counterparts. Up to 30% of older patients do not undergo any therapeutic intervention [20, 21], and many surgeons tend to be more conservative when managing older patients [20, 22]. The reluctance to operate on this population may be due to a greater percentage of complicated disease [6] and a greater comorbid disease burden [4, 21]. However, little is known about whether, even in the elderly population, age also may play a role in management strategies and whether the likelihood to treat may decrease with increasing older age.

This study aimed to describe the differences in management of symptomatic gallstone disease in different elderly groups and to evaluate the association between older age and surgical treatment.

Methods

Patients

This single-institution retrospective chart review included all patients 65 years of age and older with an initial hospital visit for symptomatic gallstone disease between 1 April 2004 and 31 May 2008. Hospital visits included elective surgery admissions and emergency department (ED) visits with or without subsequent urgent admission. Outpatient visits in the office or clinic setting were not reviewed because data for these visits were not available in the hospital charts.

To avoid time length bias, data were extracted up to 1 year after the initial visit for all patients. Patients with asymptomatic or incidental gallstones, biliary malignancy, primary choledocholithiasis (common bile duct stones found > 1 year after cholecystectomy), or pancreatitis of any etiology other than biliary were excluded from the study.

Study parameters

The demographic parameters collected included age at initial hospital visit, gender, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score. The CCI predicts the risk of death from comorbid disease using weighted scores for the following comorbidities: coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, peptic ulcer disease, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, hemiplegia, chronic renal disease, cancer, metastases, and AIDS [23]. In this study, the CCI was based on all comorbidities recorded over all visits.

The visit type was defined as ED visit only, ED visit followed by urgent admission, or elective admission. The admission ward (surgical or medical) was considered medical if the patient was admitted to both the medical and surgical wards during the same hospital stay or if the patient had been admitted only to the intensive care unit (ICU) without a previous or subsequent ward admission.

The occurrence of surgical intervention (cholecystectomy or common bile duct exploration), the approach (laparoscopic, open, or laparoscopic converted to open), and the time until surgery from the initial hospital visit were recorded. Surgery was considered elective when it occurred after elective admission and urgent when it occurred after admission from the ED. Other therapeutic interventions, including the use of percutaneous cholecystostomy and ERCP, also were documented.

For all ED visits, including ED only and ED followed by urgent admission, the diagnosis was recorded as biliary colic, cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, pancreatitis, or cholangitis. Disease was defined as uncomplicated for a diagnosis of biliary colic and as complicated for all other diagnoses. When patients were admitted directly for elective surgery, diagnoses were assigned.

This study received ethics approval from the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Statistical analysis

Patients were stratified into three age groups: group 1 (age, 65–74 years), group 2 (age, 75–84 years), and group 3 (age, ≥85 years). Descriptive statistics by age group were conducted to summarize patient characteristics at the initial hospital visit as well as the surgical and other interventions occurring over the 1-year follow-up period. Proportions were calculated for categorical variables, and means ± standard deviations were used for continuous variables.

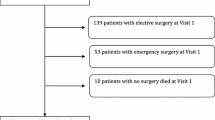

A cumulative 1-year incidence graph for surgery by age group was created, with incidence adjusted for deaths without surgery. Logistic regression was performed to assess the effect of age on surgery as a continuous variable, with adjustment for gender, CCI, and complicated disease at the initial hospital visit. Because disease complexity at the initial hospital visit could not be ascertained for elective visits, the analysis was performed excluding those visits. Moreover, patients who died without surgery also were excluded from the study.

A sensitivity analysis included the elective visits by imputing severity of diagnosis as uncomplicated. Further sensitivity analyses were performed including patients who died without surgery before the end of the follow-up period by assuming no surgery during that time. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics at the initial hospital visit

Data from 397 patient charts were assessed: 182 in group 1, 160 in group 2, and 55 in group 3. The overall mean age of the patients was 76.1 ± 7.4 years. Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics at the first recorded visit. The number of comorbidities was higher in the older groups. Half of the patients in group 1 were admitted electively at the first visit, whereas urgent admission was the most common type of visit in groups 2 and 3. All the patients admitted electively underwent surgery. Urgent surgery at the first visit was undertaken for 13.2% of group 1, 16.3% of group 2, and 5.5% of group 3.

Among the patients with an initial ED visit, cholecystitis was the most common diagnosis in groups 1 and 2, whereas cholangitis was the most common diagnosis in group 3 (Fig. 1). When choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis were considered together as representing common bile duct disease, the percentage increased from 30% in group 1 to more than 50% in group 3, driven primarily by an increase in the percentage of cholangitis, reaching 30% in group 3. When diagnoses were grouped as complicated versus noncomplicated disease at the initial visit, 70% of the patients in group 1 had a complicated disease compared with 85.7% in group 2 and 81.2% in group 3.

Results over the study period

The 1-year cumulative incidence of surgery is illustrated in Fig. 2. The incidence was adjusted for 11 patients who died without undergoing surgery (5 patients died after surgery and therefore were incidence cases). The 1-year incidence of surgery was 87.4% in group 1, 63.5% in group 2, and 22.1% in group 3.

Table 2 summarizes the therapeutic interventions that took place during the study period. The proportion of cholecystostomy and ERCP increased with increasing age. Only three patients with a cholecystostomy subsequently underwent surgery.

Among the patients who underwent ERCP, 81.8% in group 1 also had a surgery compared with 52.2% in group 2 and only 12.5% in group 3. In each group, the most common surgical approach was laparoscopic surgery. The proportion of conversions was slightly higher in group 1, whereas open surgery was more frequent in group 3.

Three patients underwent common bile duct exploration in the same sitting as cholecystectomy. An additional patient underwent common bile duct exploration, but the gallbladder was left in situ. The majority of patients in each group underwent surgery through elective admission, but the proportion was highest in group 1. Almost half of the surgery patients in each group had surgery on the first day of the initial visit (time to surgery, 0). Most of the surgeries were conducted by the end of the first month. A small number of patients in each group underwent surgery beyond 1 month.

A logistic regression showed that increased age (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.84–0.91) and CCI (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.69–0.94) were significantly associated with a decreased probability of surgery performed within 1 year (Table 3). The analysis was performed for 246 patients after the exclusion of deaths and elective visits. Sensitivity analyses showed very similar results whether deaths were included or excluded. When elective visits were included by imputation of disease severity as uncomplicated, the effect of age and CCI were similar, but disease severity also was found to be highly significant, a likely artificial effect due to the imputation.

Discussion

This study was unique in that it showed how elderly “all-comers” with gallstone disease initially present with their disease and are subsequently treated while also describing how disease presentation and management differ within stratified age groups. Acknowledging this population’s heterogeneity is critically important because age-related physiologic changes in the elderly may contribute to differences in disease manifestation and treatment response [24–26]. Not doing so, Watters warned, “exposes elderly patients to risk from inaccurate inferences” [26].

Our data showed a greater percentage of complicated gallstone disease in the older groups, which is consistent with what others have found [15, 27]. Surprisingly, the percentage of cholecystitis seemed to decrease slightly with age, although the overall percentage was situated within the range of 21 to 56% reported by other studies investigating all-comers [20, 21]. Percentages of common bile duct disease also were in line with previously reported values [20]. The number of patients requiring urgent admission also rose sharply with age, more than doubling when the youngest group was compared with the oldest group.

Open cholecystectomy was performed more often in the older groups, possibly in part because of greater disease severity, but perhaps also because of a lower threshold among our surgeons for using the open approach at the outset. Lower conversion rates in the older groups, contrary to what others have found [15, 18, 28], may be explained by selection of the less difficult cases for the laparoscopic approach. Nevertheless, the authors believe that because the benefits of minimally invasive surgery have been so clearly established in this population [29–32], laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be attempted for almost all patients, even if this means a greater incidence of conversion.

This study showed marked differences in the management strategies between the elderly groups. First, the cumulative incidence of surgery was much higher for the patients 65–74 years old (87.4%) and decreased with age to 63.5% for those 75–84 years old and to only 22.1% for those 85 years old and older. This highlights the increased use of nonoperative management with increasing age.

Second, the timing of surgery also varied across age groups. In the age strata of 65–74 years and 75–84 years, a majority of surgeries occurred within the first month. The surgeries then tapered in months 2 and 3, most likely representing patients undergoing delayed cholecystectomy after initial nonoperative management before reaching a plateau. More dramatically, for the patients 85 years old and older, all but one surgery occurred within the first month. This early plateau for the patients 85 years old and older likely suggests that the operative candidates underwent surgery almost immediately, but that the majority of these patients, having responded to initial nonoperative management, were unlikely to opt for (or need) a cholecystectomy within the following year. Even after adjustment for sex, comorbidity, and complicated disease, age remained significantly associated with a decreased incidence of surgery performed, corroborating other findings in the literature [4, 20–22].

This more conservative approach with increasing age also is reflected in the pattern of less invasive methods used for treatment. First, at the initial visit, admission to medical wards increased with age, which suggests a greater propensity to attempt medical treatment preferentially for patients in the older age range. In addition, cholecystostomy was used more often for older patients overall, up to 14.6% for patients 85 years old and older. Although cholecystostomy provides a safe alternative to surgery for the critically ill and those with prohibitive comorbidity, it also is associated with significant recurrence rates when not followed by surgery, much the same as ERCP [8, 9, 12, 33–35]. Despite this, ERCP was used with surgery much less often in the older groups. Cholecystostomy was only rarely followed by surgery in all three groups. Disease recurrence was not addressed in this analysis, but the paucity of surgical procedures performed after 3 months suggests that rescue surgery was unnecessary during this follow-up period.

Some important limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, the study was subject to the limitations inherent to chart reviews. Because only hospital charts were reviewed, the data may give an incomplete picture of the trajectory of our study population because they do not capture visits to the patients’ family doctor or surgeon in the outpatient setting. This limitation likely explains the large percentage of elective surgeries at the “first” visit. Moreover, it is not known whether the “first” visits shown on the chart were truly initial manifestations of the disease or simply initial manifestations of disease severe enough to warrant a hospital visit. Patients also may have been seen in other hospitals, although interhospital movement is generally uncommon in this population.

Second, because of differences in regional health care systems, hospital protocols, and availability of resources, the results may represent institution-specific phenomena and may not be entirely generalizable [36, 37]. Third, the CCI has not been validated for the elderly population, so the impact of certain comorbidities may be underestimated. Dementia, a factor of paramount importance in the surgical decision process, may warrant consideration as a separate comorbidity. Finally, given the small number of patients older than 85 years, the percentages in this group, particularly those related to surgery, should be interpreted with some caution.

In conclusion, the older elderly patients presented more frequently with severe disease and underwent more conservative treatment strategies throughout the study period. Moreover, older age was independently associated with a lower likelihood of surgery. This study will help in the development of a prospective study comparing the outcomes resulting from operative and nonoperative management. This will provide insight into whether these management strategies are justified and which subset of patients would benefit most from one or the other.

References

Lirussi F, Nassuato G, Passera D, Toso S, Zalunardo B, Monica F, Virgilio C, Frasson F, Okolicsanyi L (1999) Gallstone disease in an elderly population: the Silea study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 11:485–491

Festi D, Dormi A, Capodicasa S, Staniscia T, Attili AF, Loria P, Pazzi P, Mazzella G, Sama C, Roda E, Colecchia A (2008) Incidence of gallstone disease in Italy: results from a multicenter, population-based Italian study (the MICOL project). World J Gastroenterol 14:5282–5289

Ratner J, Lisbona A, Rosenbloom M, Palayew M, Szabolcsi S, Tupaz T (1991) The prevalence of gallstone disease in very old institutionalized persons. JAMA 265:902–903

Sugiyama M, Atomi Y (1997) Treatment of acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis in elderly and younger patients. Arch Surg 132:1129–1133

Wenckert A, Robertson B (1966) The natural course of gallstone disease: eleven-year review of 781 nonoperated cases. Gastroenterology 50:376–381

Urbach DR, Stukel TA, Urbach DR, Stukel TA (2005) Rate of elective cholecystectomy and the incidence of severe gallstone disease. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J 172:1015–1019

Sanson TG, O’Keefe KP (1996) Evaluation of abdominal pain in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am 14:615–627

Ashton CE, McNabb WR, Wilkinson ML, Lewis RR (1998) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in elderly patients. Age Ageing 27:683–688

Talar-Wojnarowska R, Szulc G, Wozniak B, Pazurek M, Malecka-Panas E (2009) Assessment of frequency and safety of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients over 80 years of age. Pol Arch Med Wewn 119:136–140

Howard JM, Hanly AM, Keogan M, Ryan M, Reynolds JV (2009) Percutaneous cholecystostomy: a safe option in the management of acute biliary sepsis in the elderly. Int J Surg 7:94–99

Griniatsos J, Petrou A, Pappas P, Revenas K, Karavokyros I, Michail OP, Tsigris C, Giannopoulos A, Felekouras E (2008) Percutaneous cholecystostomy without interval cholecystectomy as definitive treatment of acute cholecystitis in elderly and critically ill patients. South Med J 101:586–590

Sugiyama M, Tokuhara M, Atomi Y (1998) Is percutaneous cholecystostomy the optimal treatment for acute cholecystitis in the very elderly? World J Surg 22:459–463

Borzellino G, de Manzoni G, Ricci F, Castaldini G, Guglielmi A, Cordiano C (1999) Emergency cholecystostomy and subsequent cholecystectomy for acute gallstone cholecystitis in the elderly. Br J Surg 86:1521–1525

Bingener J, Richards ML, Schwesinger WH, Strodel WE, Sirinek KR (2003) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for elderly patients: gold standard for golden years? Arch Surg 138:531–535 discussion 535–536

Brunt LM, Quasebarth MA, Dunnegan DL, Soper NJ (2001) Outcomes analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the extremely elderly. Surg Endosc 15:700–705

Kauvar DS, Brown BD, Braswell AW, Harnisch M, Kauvar DS, Brown BD, Braswell AW, Harnisch M (2005) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the elderly: increased operative complications and conversions to laparotomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 15:379–382

Kim H-O, Yun J-W, Shin J-H, Hwang S-I, Cho Y-K, Son B-H, Yoo C-H, Park Y-L, Kim H (2009) Outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is not influenced by chronological age in the elderly. World J Gastroenterol 15:722–726

Fried GM, Clas D, Meakins JL (1994) Minimally invasive surgery in the elderly patient. Surg Clin North Am 74:375–387

Saxe A, Lawson J, Phillips E (1993) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients aged 65 or older. J Laparoendosc Surg 3:215–219

Arthur JDR, Edwards PR, Chagla LS (2003) Management of gallstone disease in the elderly. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 85:91–96

Chareton B, Letoquart JP, Lucas A, La Gamma A, Kunin N, Chaillou M, Mambrini A (1991) Cholelithiasis in patients over 75 years of age: apropos of 147 cases. J Chir 128:399–402

Siegel JH, Kasmin FE (1997) Biliary tract diseases in the elderly: management and outcomes. Gut 41:433–435

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis 40:373–383

Rosenthal RA, Andersen DK (1993) Surgery in the elderly: observations on the pathophysiology and treatment of cholelithiasis. Exper Gerontol 28:459–472

Ross SO, Forsmark CE (2001) Pancreatic and biliary disorders in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 30:531–545

Watters JM, Watters JM (2002) Surgery in the elderly. Can J Surg 45:104–108

Harness JK, Strodel WE, Talsma SE (1986) Symptomatic biliary tract disease in the elderly patient. Am Surg 52:442–445

Mayol J, Martinez-Sarmiento J, Tamayo FJ, Fernandez-Represa JA (1997) Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the ageing patient. Age Ageing 26:77–81

Pessaux P, Regenet N, Tuech JJ, Rouge C, Bergamaschi R, Arnaud JP (2001) Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy: a prospective comparative study in the elderly with acute cholecystitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 11:252–255

Maxwell JG, Tyler BA, Rutledge R, Brinker CC, Maxwell BG, Covington DL (1998) Cholecystectomy in patients aged 80 and older. Am J Surg 176:627–631

Fisichella PMA, Di Stefano A, Di Carlo I, La Greca G, Russello D, Latteri F (2002) Efficacy and safety of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly: a case-controlled comparison with the open approach. Ann Ital Chir 73:149–153 discussion 153–144

Lujan JA, Sanchez-Bueno F, Parrilla P, Robles R, Torralba JA, Gonzalez-Costea R (1998) Laparoscopic vs. open cholecystectomy in patients aged 65 and older. Surg Laparosc Endosc 8:208–210

Spira RM, Nissan A, Zamir O, Cohen T, Fields SI, Freund HR (2002) Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy and delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy in critically ill patients with acute calculus cholecystitis. Am J Surg 183:62–66

Li JCM, Lee DWH, Lai CW, Li ACN, Chu DW, Chan ACW (2004) Percutaneous cholecystostomy for the treatment of acute cholecystitis in the critically ill and elderly. Hong Kong Med J 10:389–393

Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, Janssen IM, Bolwerk CJ, Timmer R, Boerma EJ, Obertop H, Huibregtse K, Gouma DJ, Boerma D, Rauws EAJ, Keulemans YCA, Janssen IMC, Bolwerk CJM, Timmer R, Boerma EJ, Obertop H, Huibregtse K, Gouma DJ (2002) Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet 360:761–765

Laycock WS, Siewers AE, Birkmeyer CM, Wennberg DE, Birkmeyer JD (2000) Variation in the use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for elderly patients with acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg 135:457–462

Makela JT, Kiviniemi H, Laitinen S, Makela JT, Kiviniemi H, Laitinen S (2005) Acute cholecystitis in the elderly. Hepatogastroenterology 52:999–1004

Disclosures

Simon Bergman, Nadia Sourial, Isabelle Vedel, Wael C. Hanna, Shannon A. Fraser, Daniel Newman, Aaron J. Bilek, Christos Galatas, Jonah E. Marek, and Johanne Monette have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented at the 12th WCES, April 14--17, 2010, National Harbor, MD.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bergman, S., Sourial, N., Vedel, I. et al. Gallstone disease in the elderly: are older patients managed differently?. Surg Endosc 25, 55–61 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1128-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1128-5