Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) has not gained widespread acceptance because of technical difficulties, especially esophagojejunal anastomosis. Various modified procedures for reconstruction have been reported, but an optimal method has not been established. The authors report a circular-stapled anastomosis using hand-sewn purse-string sutures, which is a simple and classic method. However, no previous study has assessed its reliability.

Methods

From September 2008 to May 2009, 10 consecutive patients (9 men and 1 woman) with gastric cancer underwent LTG at the authors’ institution. These patients had a median age of 63.7 years (range, 45–80 years) and a body mass index of 22.4 kg/m2 (range, 18–26 kg/m2). After transection of the abdominal esophagus, a hand-sewn purse-string suture along the cut end of the esophagus was performed using 3-0 monofilament thread. An anvil head then was inserted into the esophagus, and the thread was tied. A monofilament pretied loop suture was added to reinforce the ligation. After the creation of an Roux-en-Y jejunal limb, laparoscopic esophagojejunal anastomosis was performed using a circular stapler inserted via a surgical glove attached to a wound retractor at the incision point at the umbilicus. The jejunal stump was closed with an endoscopic linear stapler.

Results

Laparoscopic esophagojejunostomy was performed successfully for all the patients. No postoperative complications related to anastomosis occurred. In one patient, an intraabdominal abscess developed postoperatively and was treated conservatively. The mean operation time was 257 min, and the estimated blood loss was 69 ml.

Conclusions

With the described method, esophagojejunostomy can be performed as in conventional open surgery. Hand-sewn purse-string suturing is demanding technically, but it can be performed safely by experienced laparoscopic surgeons. This technique is feasible and can lower the cost of the laparoscopic procedure. It may be considered in countries with limited access to other special devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The techniques for laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) in the treatment of early gastric cancer have been established. For early gastric cancer, LDG has many advantages such as reduced surgical invasiveness, faster recovery of bowel function, less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, and acceptable long-term outcomes [1, 2].

In contrast, laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) has not gained such widespread acceptance as LDG [3, 4]. This slow acceptance may be associated with a lower incidence of early cancer requiring LTG and its technical difficulties, especially the reconstruction procedures of esophagojejunostomy. In conventional total gastrectomy at laparotomy, circular-stapled esophagojejunostomy, a standard technique, is the most commonly performed. With this technique, an anvil head is inserted into the abdominal esophagus, and fixed using a purse-string suture.

Also with LTG, several groups have reported the use of extracorporeal esophagojejunostomy through minilaparotomy, similar to conventional surgery [5, 6]. However, with such a procedure, it is sometimes difficult to complete anastomosis. In particular, insertion and fixation of the anvil head through minilaparotomy is a troublesome task in the narrow and deep operating fields. This would be more difficult in obese patients, and extension of the incision for laparotomy may be required. Intracorporeal anastomosis using such a technique appears to be ideal because it may be applied easily to obese patients. However, it still is thought to be a difficult procedure. The most important technical problem is how to place and fix the anvil head using a purse-string suture at the esophageal stump under laparoscopic vision.

Several authors have sought for alternative procedures to simplify this technique [7–12]. However, these procedures still appear to be complicated and have not been accepted widely.

Laparoscopic hand-sewn purse-string suturing using a conventional needledriver at the esophageal stump is a simple method for fixing the anvil head. This technique, considered extremely difficult or impossible, has long been avoided by surgeons. To the best of our knowledge, no study has assessed the reliability of this technique or described its technical details, although it is a simple and classic method. The current study aimed to assess whether it is feasible for LTG or not.

Materials and methods

Patients

From September 2008 to May 2009, 10 consecutive patients (9 men and 1 woman) with gastric cancer underwent LTG at our institution. These patients had a median age of 63.7 years (range, 45–80 years) and a body mass index of 22.4 kg/m2 (range, 18–26 kg/m2). The diagnosis for all the patients was gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach without lymph node involvement. Preoperative staging was based on gastrointestinal endoscopy, barium swallowing, and abdominal computed tomography (CT).

Surgeon

All the operations were performed by an experienced laparoscopic surgeon familiar with intracorporeal suturing and knot-tying techniques.

Surgical techniques

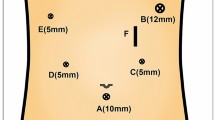

The patient was placed in a modified lithotomy position. The surgeon stood on the right side of the patient, with the first assistant on the left side and the laparoscope operator between the patient’s legs. After a carbon dioxide (CO2) pneumoperitoneum had been established through the umbilical port, four operating ports were created in the upper abdomen, as shown in Fig. 1.

The left lobe of the liver was retracted using a Penrose drain to expose the anatomy around the esophagogastric junction, as reported by Sakaguchi et al. [13]. After full mobilization of the stomach, the abdominal esophagus was exposed completely.

Radical lymphadenectomy was performed in all the patients. A detachable bowel clamp (Endo intestinal clip; Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany) was placed at the esophagus to avoid its withdrawal into the mediastinum after subsequent transection. The esophagus was transected perpendicularly with electrocautery scissors at the level of the esophagogastric junction. The umbilical port was extended longitudinally to a length of 3.5 cm, then retracted and protected by a wound retractor (Alexis Wound Retractor S; Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA).

The stomach was extracted, and the anvil head of a 25-mm circular stapler (ECS; Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) was introduced into the abdominal cavity by minilaparotomy. A surgical glove was attached to the wound retractor to maintain airtightness, and pneumoperitoneum was reestablished. A needledriver and an assistant forceps (Parrot & Flamingo, Karl-Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) were introduced into the abdominal cavity through bilateral subcostal ports with a 25-cm-long, 3-0 monofilament suture using a 26-mm curved needle.

A hand-sewn purse-string suture along the cut end of the esophagus with a full-thickness stitch, from outside or inside alternatively, was performed (Fig. 2A). The suture was started from the left side of the esophageal stump to encircle it in a counterclockwise direction from the surgeon. Most of the suturing could be done in forehand style by a needleholder grasped with the right hand, and in some situations, the needle could be used in backhand style (Fig. 2A, B). Normally, the purse-string running suture required approximately 14 stitches altogether.

Schematic outline of a hand-sewn purse-string suture and fixation of an anvil head. A, B Purse-string suture at the esophageal cut end was performed in forehand or backhand style. C The esophageal lumen was opened gently by two bowel forceps, and the anvil head was introduced using an anvil-holding forceps. D Once the anvil head was well positioned, the thread was pulled and tied. E An additional pretied loop suture was placed for reinforcement of the ligation

After the purse-string suture was completed, a double half-knot was made intracorporeally in advance, and metal clips were placed on the distal side of the thread so as not to come untied. Scopolamine was administrated, and the detachable bowel clamp was removed from the esophagus. The esophageal lumen was opened gently toward the right and left by bowel forceps, and the anvil head was introduced using an anvil-holding forceps from its rim similar to fastening a button (Fig. 2C).

Once the anvil head was positioned correctly, the thread was pulled to fix it in place, and an additional half-knot was made (Fig. 2D). In all cases, a monofilament pretied loop (Endoloop; Ethicon Endosurgery) was applied to reinforce the ligation (Fig. 2A, E).

Reconstruction was performed by the Roux-en-Y method. A jejunojejunal anastomosis (Y anastomosis) was performed side to side using an endoscopic linear stapler to create a 40-cm Roux-en-Y limb. The Roux limb was positioned in an antecolic manner. The body of the circular stapler was introduced through a surgical glove for intracorporeal use. The circular stapler was inserted into the distal limb of the jejunum, which was tied by a cotton tape to prevent slippage of the jejunum from the circular stapler during the intracorporeal procedures. The surgical glove was attached to the wound retractor to maintain the pneumoperitoneum.

The tip of the circular stapler was introduced into the abdominal cavity, and a laparoscope was introduced via the left lower port. The circular stapler was combined with the anvil head under laparoscopic vision (Fig. 3B), and after anastomosis, the circular stapler was withdrawn. Finally, the jejunal stump was closed using an endoscopic linear stapler (Fig. 3C).

The esophagojejunostomy was immersed in normal saline and tested for leaks by infusing air into the pouch lumen via a nasogastric tube and looking for escaping bubbles. The abdominal cavity was checked, and a silicon drainage tube was placed through a port site around the esophagojejunal anastomosis.

Results

All the patients successfully underwent the aforementioned operation without any intraoperative complications. No case required conversion to open surgery. The mean operation time was 257 min (range, 212–302 min), and the estimated blood loss was 69 ml (range, 5–187 ml). The mean time for purse-string suturing was 6 min (range, 5–7 min).

No patient required extension of the initial incision for difficulties during anastomosis. All the resected specimens had tumor-free resection margins, and the mean number of harvested lymph nodes was 43.3 (range, 24–95).

One patient experienced intraabdominal abscess postoperatively. For this patient, postoperative fluorography was performed on day 7, which demonstrated no anastomotic leak. The patient was treated conservatively with antibiotics. No other surgical complications (e.g., wound infection or pancreatitis) occurred. The median postoperative time until clear liquids could be received was 4 days (range, 2–10 days). No anastomotic leak or stenosis occurred. The median postoperative hospital stay was 13 days (range, 8–24 days). There was no mortality.

Discussion

The LDG technique has been almost fully established, and many patients have undergone LDG, especially in Eastern countries [1, 2]. In contrast, LTG has not gained wide acceptance to date for several reasons, such as lower incidences of patients who require LTG and its technical difficulties [3, 4]. In particular, reconstruction procedures for LTG are controversial, and the optimal method for esophagojejunostomy in LTG remains to be established.

Previously, we have performed extracorporeal esophagojejunostomy [5, 6]. However, it is sometimes difficult to complete anastomosis by minilaparotomy in the narrow and deep operating fields. This procedure is likely to be affected by the size of the patient, and in obese patients, we had to enlarge the incision to about 10 cm.

Several groups have reported laparoscopic side-to-side anastomosis using a linear stapler for esophagojejunostomy in LTG [11]. Such a technique seems favorable for laparoscopic surgery because the use of linear staplers is easier under the limited laparoscopic vision than the use of circular staplers. This appears to be an excellent procedure, but it requires taking down the esophagus longer toward the mediastinum than usual to secure the distance for anastomosis. This manipulation carries the potential risk of subsequent mediastinitis if leakage occurs.

We perform esophagojejunostomy using a circular rather than a linear stapler. The insertion and fixation of the anvil head is performed in a manner similar to that in open surgery. Such a procedure under laparoscopic vision is thought to be extremely difficult or impossible because of some technical problems. First, hand-sewn purse-string suturing under laparoscopy is demanding technically. Insufficient suturing may cause loosening of ligation, which leads to anastomotic problems. Second, insertion of the anvil head into the esophageal lumen under laparoscopic vision is considered to be much more difficult than in open surgery. Excessive force may cause tearing of the esophageal wall, which also may lead to anastomotic problems.

Actually, we performed these procedures successfully without loosening of the suture or anastomotic leakage. The purse-string sutures were performed meticulously by a very experienced laparoscopic surgeon. If the ligation seemed insufficient after tying, an additional pretied loop suture could be placed for reinforcement, which was effective at securing the ligation. In our patients, a 25-mm anvil head, the standard size for Japanese patients undergoing esophagojejunostomy, could be inserted in all cases. We think that the most important point is to expose the esophageal lumen by two bowel graspers in opposite directions and to insert the anvil head gently and accurately from its rim. The esophageal lumen was more clearly visible than with the direct view in open surgery.

To date, several researchers have published modified procedures for circular-stapled esophagojejunostomy in LTG that do not require hand sewing. Recently, a method for transoral insertion of the anvil head and subsequent double-stapling esophagojejunostomy has been reported [12]. Although this method is possible theoretically, transoral passage of the anvil head potentially carries the risk of esophageal injury in some narrow spaces such as the larynx and the esophagus at the level of the tracheal bifurcation. Once such esophageal injury occurs, it seems difficult to recover it. The incidence of such injury may be very low, but it is not zero.

Hiki et al. [8] and Omori et al. [10] have reported other double-stapling anastomosis methods. They have mentioned that the anvil head is inserted into the esophagus from the opening on the anterior wall in advance, which is pulled down after stapled transection of the esophagus. Currently, however, neither safety nor long-term outcomes of these double-stapling techniques, including stenosis, has been established.

Usui et al. [9] have reported a newly designed device for purse-string suturing in LTG, with excellent outcomes. Unfortunately, this device currently is available only in Japan and Korea and has not become widely available. Takiguchi et al. [7] have reported a laparoscopic purse-string suture using a semiautomatic disposable suture device (Endostitch; Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) in LTG. Except for the method of purse-string suturing, these two procedures are relatively similar to ours. It is not clear whether the reconstruction of LTG really has been simplified with these techniques. In addition, not much consideration has been given to the cost of these procedures or their long-term outcomes. We believe that consideration should be given to countries with limited access to new specialized devices.

Our technique presented in this report is very simple and can be performed with only a conventional laparoscopic needledriver and a circular stapler. As other authors have mentioned, laparoscopic hand-sewn suturing for the intestinal tract is demanding technically. However, intestinal anastomosis using these techniques has been performed widely in the field of bariatric surgery [14]. Our results indicate that laparoscopic hand-sewn purse-string suturing is not difficult for skilled laparoscopic surgeons.

The optimal method for esophagojejunostomy in LTG remains to be established. Probably, there is not one single optimal method currently. As we have shown, laparoscopic hand-sewn purse-string suturing can be safely and rapidly performed by surgeons familiar with intracorporeal suturing and knot-tying techniques. This technique is feasible and can lower the cost of the laparoscopic procedure, and it may be considered in countries with limited access to other special devices.

References

Shehzad K, Mohiuddin K, Nizami S, Sharma H, Khan IM, Memon B, Memon MA (2007) Current status of minimal access surgery for gastric cancer. Surg Oncol 16:85–98

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N, Japanese Laparoscopic Surgery Study Group (2007) A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg 245:68–72

Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Brachini G, Binda B, Di Paola M, Ponzano C (2007) Totally laparoscopic total and subtotal gastrectomy with extended lymph node dissection for early and advanced gastric cancer: early and long-term results of a 100-patient series. Am J Surg 194:839–844

Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Kishida S, Ogata A, Fujiwara Y, Osugi H (2007) Laparoscopic gastrectomy with regional lymph node dissection for upper gastric cancer. Br J Surg 94:204–207

Okabe H, Satoh S, Inoue H, Kondo M, Kawamura J, Nomura A, Nagayama S, Hasegawa S, Itami A, Watanabe G, Sakai Y (2007) Esophagojejunostomy through minilaparotomy after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer 10:176–180

Kim SG, Lee YJ, Ha WS, Jung EJ, Ju YT, Jeong CY, Hong SC, Choi SK, Park ST, Bae K (2008) LATG with extracorporeal esophagojejunostomy: is this minimal invasive surgery for gastric cancer? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 18:572–578

Takiguchi S, Sekimoto M, Fujiwara Y, Miyata H, Yasuda T, Doki Y, Yano M, Monden M (2005) A simple technique for performing laparoscopic purse-string suturing during circular stapling anastomosis. Surg Today 35:896–899

Hiki N, Fukunaga T, Yamaguchi T, Nunobe S, Tokunaga M, Ohyama S, Seto Y, Muto T (2007) Laparoscopic esophagogastric circular stapled anastomosis: a modified technique to protect the esophagus. Gastric Cancer 10:181–186

Usui S, Nagai K, Hiranuma S, Takiguchi N, Matsumoto A, Sanada (2008) Laparoscopy-assisted esophagoenteral anastomosis using endoscopic purse-string suture instrument “Endo-PSI (II)” and circular stapler. Gastric Cancer 11:233–237

Omori T, Oyama T, Mizutani S, Tori M, Nakajima K, Akamatsu H, Nakahara M, Nishida T (2009) A simple and safe technique for esophagojejunostomy using the hemidouble stapling technique in laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy. Am J Surg 197:e13–e17

Okabe H, Obama K, Tanaka E, Nomura A, Kawamura JI, Nagayama S, Itami A, Watanabe G, Kanaya S, Sakai Y (2009) Intracorporeal esophagojejunal anastomosis after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 23:2167–2171

Jeong O, Park YK (2009) Intracorporeal circular stapling esophagojejunostomy using the transorally inserted anvil (OrVil) after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0461-z

Sakaguchi Y, Ikeda O, Toh Y, Aoki Y, Harimoto N, Taomoto J, Masuda T, Ohga T, Adachi E, Okamura T (2008) New technique for the retraction of the liver in laparoscopic gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 22:2532–2534

Ruiz-de-Adana JC, López-Herrero J, Hernández-Matías A, Colao-Garcia L, Muros-Bayo JM, Bertomeu-Garcia A, Limones-Esteban M (2008) Laparoscopic hand-sewn gastrojejunal anastomoses. Obes Surg 18:1074–1076

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Shigeyuki Sakaguchi for his preparation of the schematic illustrations.

Disclosures

Takahiro Kinoshita, Takashi Oshiro, Katsuhiko Ito, Hidehito Shibasaki, Shinichi Okazumi, and Ryoji Katoh have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kinoshita, T., Oshiro, T., Ito, K. et al. Intracorporeal circular-stapled esophagojejunostomy using hand-sewn purse-string suture after laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 24, 2908–2912 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1041-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1041-y