Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the role that laparoscopy plays in the management of gallbladder cancer.

Method

From August 2005 to March 2009, 23 patients affected by gallbladder cancer detected after the study of a cholecystectomy specimen underwent laparoscopy as part of their management.

Results

Among the patients, 5 underwent only an exploratory laparoscopy, while 11 were converted due to the existence of dense adhesions that precluded a complete exploration. Of the patients with adhesions who underwent conversion, three were unresectable. The remainder underwent a lymphadenectomy and liver resection after conversion. Of the seven who underwent a complete laparoscopic exploration, five had a lymphadenectomy and liver resection done completely by laparoscopy while conversion was needed for two. Conversion was required due to lymphatic metastasis at the hepatic pedicle and the presence of a bile leak. Postoperative time was uneventful, with patients discharged within 3 days of the operation.

Conclusions

Laparoscopy may be employed in the management of patients with early forms of gallbladder cancer undergoing reoperation. Although the presence of adhesions may result in inadequate exploration, there is a subset of patients for whom it is possible to perform a complete exam. Furthermore, laparoscopic lymphadenectomy and gallbladder bed resection is a promising technique in well-selected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gallbladder cancer is a relatively uncommon neoplasm worldwide but shows significant geographic differences. In Chile, the disease has an extremely high incidence and is the main cause of oncological death among women [1, 2].

Despite the large number of lesions detected when the disease is too advanced and the prognosis is poor, there are a number of patients in whom the tumor is detected at earlier stages. Most of these cases are tumors detected after the detailed examination of a cholecystectomy specimen [3–5]. In these cases, a reoperation to perform a complete lymph node dissection associated with the resection of a portion of the liver is recommended.

After the introduction of laparoscopy, oncological surgery was not included among the indications; however, laparoscopy for certain types of diseases was gradually accepted. At present, colon cancer represents an unquestionable indication and other types of pathologies such as tumors of the liver and pancreas are under study protocols [6–11]. With the above in mind, we have devised a therapeutic protocol for gallbladder cancer employing laparoscopy.

Materials and methods

The laparoscopic approach was employed with two objectives: (1) to evaluate resectability in a minimally invasive manner and (2) to use it as a definitive way to dissect the lymph nodes of the hepatic pedicle and resect the gallbladder bed. At the beginning of the protocol, the main objective was to assess resectability, and resection has been included for the last 3 years.

To be included in the protocol, patients had to have already undergone a cholecystectomy and been diagnosed with cancer after examination of the cholecystectomy specimen. During patient evaluation it is important to know details of the operative findings of any previous cholecystectomy. Patients were evaluated by physical exam, laboratory tests, and abdominal CT scan. The cholecystectomy specimen was completely re-examined to verify the level of wall invasion. Once the cholecystectomy report and CT scan was analyzed, candidates for the laparoscopic approach were categorized as potentially resectable [3]. Although the probability of completing a laparoscopic resection is lower in patients who have previously undergone an open cholecystectomy, those patients were also included. Patients received a consultation about their disease, prognosis, and treatment alternatives and were free to accept or decline the laparoscopic approach and reoperation.

Operations were performed with the patient under general anesthesia. Patients were placed in the French position, with the primary surgeon between the legs. In those cases in which the previous procedure was done laparoscopically, pneumoperitoneum was performed by introducing a Veress needle. In those cases in which an open procedure was initially performed, we preferred to use an open approach.

Patients were placed in a moderate fawler and left lateral decubitus position. Pneumoperitoneum was induced at a pressure of 15 mm and reduced to a level lower than 12 mmHg to prevent a gas embolism during the liver resection. We used four 10-mm trocars and a 30° laparoscope. The first trocar was placed at the umbilicus while the other trocars were placed at the right and left hypochondrious and the right flank, respectively. A 5-mm trocar was placed at the left flank. All ports used for stapling had to be placed an adequate distance from the liver substance to allow jaw articulation.

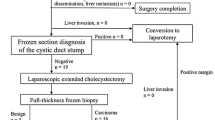

The procedure began by examining the abdominal cavity. The areas adjacent to the duodenum, gallbladder bed, peritoneum, and liver surface were carefully scrutinized. The hepatic flexure and transverse colon were mobilized down, exposing the entire second and third part of the duodenum. Contraindications to carry on with the resection were peritoneal implants, compromise of neighboring organs, and diffuse infiltration of the hepatic pedicle. If no contraindication for resection was observed, we freed the duodenal adhesion and performed a Kocher maneuver to reach the para-aortic space. At this level and by using a harmonic scalp (Ultrasicion, Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA), the para-aortic lymph nodes were dissected. One or two nodes were sent for frozen section analysis. In the event of a positive biopsy, the operation was finished. As part of our protocol, the next step was the extirpation of the right prerenal peritoneum. This procedure is performed to extirpate potentially compromised areas.

Dissection of the hepatic pedicle was begun, and the common bile duct, hepatic artery, and portal vein were completely dissected (Fig. 1). All the lymph nodes were sent for frozen section. If cancer cells were found in any lymph node, the operation was converted to an open procedure.

Before beginning with the liver resection, tape was placed around the porta hepatis as a tourniquet. The Pringle maneuver was used only in cases of excessive bleeding. The area to be resected, which included part of segments V and IVb, was marked by electrocautery The liver transection was performed using a harmonic scalpel (Fig. 2). Minor vessels and biliary radicles were controlled with clips or the harmonic scalpel. Upon completion of the liver resection, we dealt with the pedicle to segment V. After isolating the pedicle, it was sectioned using linear staplers (white vascular cartridge). Careful observation of the raw surface was performed and bleeding points were controlled by bi- or monopolar coagulation. The resected specimen was removed in a bag through one of the abdominal ports which was enlarged to allow specimen extraction. A Jackson Pratt drain was left at the level of the hepatic pedicle.

Results

From August 2005 to March 2009, twenty-three patients with gallbladder cancer diagnosed after the study of the cholecystectomy specimen were included in the study. Of these patients, 20 were female and 3 were male, ranging in age from 38 to 74 years (average age = 59). Eighteen had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy while 5 had an open cholecystectomy. Wall involvement of patients who underwent laparoscopy is given in Table 1. Most patients had tumor invasion limited to the subserosal layer.

All patients underwent a CT scan as part of preoperative staging. The CT scan suggested tumor recurrence in two patients. In one patient, the CT scan finding was confirmed during the laparoscopy, while in the other patient, radiological findings were due to inflammatory changes.

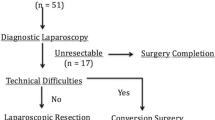

Of the 23 patients in the study, five underwent only laparoscopic exploration because of peritoneal recurrence in two patients, a neighboring organ invasion in one, a subhepatic abscess in one, and a coagulation minor alteration that precluded a further procedure in one patient.

Since the presence of dense adhesions rendered a complete exploration impossible, 11 patients had to be converted to an open procedure. Of these, tumor involvement in the pedicle area that contraindicated resection was observed in three patients. In addition, poor visualization was due only to inflammatory adhesions in eight patients. These patients underwent a lymphadenectomy of the hepatic pedicle and resection of the gallbladder bed.

Finally, in the remaining seven patients, laparoscopy enabled a complete evaluation of the abdominal cavity, including the hepatic pedicle and the gallbladder bed. All these patients had had a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In these patients, para-aortic lymph nodes were extirpated and sent for frozen section. Following the biopsy of the para-aortic lymph nodes, prerenal peritoneum was resected and sent for definitive biopsy. In the absence of para-aortic compromise, a lymphadenectomy of the hepatic pedicle was performed. Multiple nodes were sent for frozen section; malignancy was found in one patient. According to the protocol, this patient was converted and the operation was finished by an open approach. In addition to this patient, the presence of a small amount of bile coming from the upper portion of the porta hepatis was the indication for conversion in another patient. The origin of the bile was a small radicle in the hepatic tissue and no additional procedure was necessary. Among the patients who underwent resection, no transfusion was needed and the postoperative period was uneventful. The pathology exam of the laparoscopically resected specimen did not show lymph node compromise, except that of the patient who underwent conversion due to choledochoduodenal lymph node involvement. No liver specimen shows compromise. In the seven patients who underwent a laparoscopic lymphadenectomy, the number of lymph nodes dissected ranged from 3 to 12, with an average of 5.8. These numbers did not vary from those who underwent an open lymphadenectomy. Patients were discharged 3 days after the surgery without complications.

The five patients who underwent laparoscopic liver resection associated with the lymphadenectomy of the hepatic pedicle are alive with a follow-up of 12–37 (average = 22) months. One patient developed peritoneal recurrence after 31 months while the rest are free of recurrence (see Fig. 3).

Discussion

Since the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, laparoscopy has become the common way of dealing with a large number of abdominal diseases. Although the procedure was initially contraindicated for dealing with malignancies, after the satisfactory results obtained with the laparoscopic management of colon cancer, this method began to be used for treating other malignancies [6]. Complex procedures such as the Whipple procedure and extensive liver resections have also been successfully performed laparoscopically [8–14].

At the beginning of the laparoscopic era, reports about the presence of cancer cells at the level of the trocar holes were published [15, 16]. This fact brought a cautionary note about the use of laparoscopy in patients in whom gallbladder cancer was suspected because this disease has a formal contraindication for laparoscopy. Further studies have shown that perforation of the gallbladder during laparoscopic cholecystectomy would be responsible for the worsened prognosis, not the laparoscopic method itself [17]. This finding and the previous experience with laparoscopy in other malignancies allow exploration of the use of this method in the management of gallbladder cancer diagnosed after a cholecystectomy.

How to treat gallbladder cancer patients diagnosed after examination of the cholecystectomy specimen remains controversial. In general, patients who have gallbladder cancer with infiltration confined to the mucosa are thought to be cured after a simple cholecystectomy, but for those with a more advanced tumor, the debate about the best way to deal with the disease continues [3–5, 18–20]. Traditionally, patients are reoperated using an open approach with the aim of performing a lymphadenectomy of the hepatic pedicle and the retropancreatic area and resecting a portion of the liver adjacent to the gallbladder bed. The size of the liver resection is controversial but at least 2 cm adjacent to the gallbladder bed has been advocated. With this in mind, and taking into account that the gallbladder had already been extirpated, we delineated a protocol to deal laparoscopically with patients whose gallbladder cancer had already been diagnosed and a reoperation indicated. In this particular group of patients, the goal of the reoperation is to completely stage the disease and to extirpate potentially compromised areas. The operative procedure has the same objectives as the open procedure. We decided that conversion to the open approach should be carried out for those patients in whom lymph node or liver infiltration was found. This indication for conversion was adopted to obtain a larger number of patients managed by this approach and to validate our results.

A lymphadenectomy of the hepatic pedicle can be performed safely by laparoscopy. A 30° scope makes it possible to visualize the pedicle completely from different angles. A comparison of the number of lymph nodes extirpated by laparoscopy with that removed by the open method revealed that the number did not differ significantly between the two methods.

The liver transection technique we use does not differ from those reported in other laparoscopic series. The initial Glisson capsule transection is performed by electrocautery. The parenchyma is then transected with the harmonic scalpel. The main drawback of this method is the longer time it takes to transect the liver. Laparoscopic tissue link and an ultrasonic dissector have also been employed to accomplish this part of the operation [21].

Many authors have expressed concern about the risk of an air embolism associated with the pneumoperitoneum; however, current evidence does not support this theory as the use of even higher abdominal pressures than we use has been reported [21]. In our patients, we decided to keep abdominal pressure at 12 mmHg during the liver transection, but we do agree with Buell et al. [21] that there is lack of evidence supporting the need to use a lower intra-abdominal pressure during the liver transection.

The small number of patients in our study who underwent laparoscopic resection does not allow conclusions to be reached regarding the effect of this approach on survival. The postoperative period of these patients did not differ from that of patients who underwent an open approach in terms of survival. Given the difficulty of performing a prospective randomized trial, a longer follow-up period and a greater number of patients are needed to get more definitive results.

In conclusion, we can say that laparoscopy may have a role in treating patients with gallbladder cancer that is detected after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On the one hand, use of a minimally invasive procedure would enable us to stage patients, thus avoiding larger incisions and a longer postoperative recovery. On the other hand, in those patients whose local conditions make it possible to continue with the resection, a lymphadenectomy and a liver resection can be performed laparoscopically without compromising any oncological principles.

References

Wistuba I, Gazdar AF (2004) Gallbladder cancer lessons from a rare tumor. Nat Rev Cancer 4:695–706

Andia M, Gederlini A, Ferreccio C (2006) Gallbladder cancer: trend and risk distribution in Chile. Rev Med Chile 134:565–574

De Aretxabala X, Roa I, Burgos L, Losada H, Roa JC, Mora J, Hepp J, Leon J, Maluenda F (2006) Gallbladder cancer: an analysis of a series of 139 patients with invasion restricted to the subserosal layer. J Gastrointest Surg 10:186–192

Chan SY, Poon RT, Lo CM, Ng KK, Fan ST (2008) Management of carcinoma of the gallbladder: a single institution experience in 16 years. J Surg Oncol 97:156–164

Dixon E, Vollmer CM, Sahajpal A, Cattral M, Grant D, Doig C, Hemming A, Taylor B, Langer B, Greig P, Gallinger S (2005) An aggressive surgical approach leads to improved survival in patients with gallbladder cancer. A 12-year study at a North American Center. Ann Surg 241:385–394

Nelson H, Sargent DJ, Wieand HS, Fleshman J, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RWJ, Hellinger M, Flanagan R, Peters W, Ota DA (2004) Comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. The clinical outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. New Engl J Med 350:2051–2059

Ng KH, Ng DC, Cheung HY, Wong JC, Yau KK, Chung CC, Li MK (2009) Laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer: lessons learned from 579 cases. Ann Surg 249:82–86

Vibert E, Perniceni T, Levard H, Denet C, Shahri NK, Gayet B (2006) Laparoscopic liver resection. Br J Surg 93:67–72

Troisi R, Montalti R, Smeets P, Van Huysse J, Van Vlierberghe H, Colle I, De Gendt S, de Hemptinne B (2008) The value of laparoscopic liver surgery for solid benign hepatic tumors. Surg Endosc 22:38–44

Mala T, Edwin B (2005) Role and limitations of laparoscopic liver resection of colorectal metastases. Dig Dis 23:142–150

Palanivelu C, Jani K, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Rajapandian S, Madhankumar MV (2007) Laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy: technique and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 205:222–229

Gagner M, Pomp A (1994) Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc 8:408–410

Lanyhaler M, Freund M, Nehoda H (2005) Laparoscopic resection of a giant liver hemangioma, case report. J Laparosc Adv Surg Tech 15:624–626

Gagner M, Rogula T, Selzer D (2004) Laparoscopic liver resection: benefit and controversies. Surg Clin North Am 84:451–462

Schaeff B, Paolucci V, Thomopoulus J (1998) Port site recurrences after laparoscopic surgery. A review. Dig Surg 15:124–134

Ohmura Y, Yokoyama N, Tanada M, Takiyama W, Takashima S (1999) Port site recurrence of unexpected gallbladder carcinoma after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a report of a case. Surg Today 29:71–75

Z′graggen K, Birrer S, Maurer CA, Wehrli H, Klaiber C, Baer HU (1998) Incidence of port site recurrence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for preoperatively unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma. Surgery 124:831–838

Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, Muto T (1992) Inapparent carcinoma of the gallbladder. An appraisal of a radical second operation after simple cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 215:326–331

Do You D, Geun Lee H, Yeol Paik K, Seok Heo J, Ho Choi S, Wook Choi D (2008) What is an adequate extent of resection for T1? Ann Surg 247:835–838

Wakai T, Shirai N, Yokoyama N, Nagakura S, Watanabe H, Hatakeyama K (2001) Early gallbladder carcinoma does not warrant radical resection. Br J Surg 88:675–678

Buell JF, Koffron AJ, Thomas MJ, Rudich S, Abecassis M, Woodle S (2005) Laparoscopic liver resection. J Am Coll Surg 200:472–480

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Fondecyt grant 1060375 and the generosity of the Clinica Alemana Santiago.

Disclosures

Drs. de Aretxabala, Leon, Hepp, Maluenda, and Roa have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Aretxabala, X., Leon, J., Hepp, J. et al. Gallbladder cancer: role of laparoscopy in the management of potentially resectable tumors. Surg Endosc 24, 2192–2196 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0925-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0925-1