Abstract

Background

In recent years, laparoscopic gastrectomy has been applied for the treatment of gastric cancer in Japan and Western countries. This report describes the short- and long-term results for patients with gastric cancer who underwent laparoscopically assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) with lymph node dissection.

Methods

From September 1999 to December 2007, 20 patients underwent LATG, and 18 underwent conventional open total gastrectomy (OTG) for upper and middle gastric cancer. The indications for LATG included depth of tumor invasion limited to the mucosa or submucosa and absence of lymph node metastases in preoperative examinations. The LATG and OTG procedures for gastric cancer were compared in terms of pathologic findings, operative outcome, complications, and survival.

Results

No significant difference was found between LATG and OTG in terms of operation time (254 vs 248 min.), number of lymph nodes (26 vs 35), complication rate (25% vs 17%), or 5-year cumulative survival rate (95% vs 90.9%). Differences between LATG and OTG were found with regard to blood loss (299 vs 758 g) and postoperative hospitalization (19 vs 29 days).

Conclusion

For properly selected patients, laparoscopically assisted total gastrectomy can be a curative and minimally invasive treatment for early gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, laparoscopic gastrectomy has been applied for the treatment of gastric cancer in Japan and Western countries [1–3]. Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy with perigastric lymph node dissection for early gastric cancer is reported to improve postoperative quality of life [4, 5]. Laparoscopically assisted gastrectomy currently is performed not only as distal gastrectomy but also as proximal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy [6–8]. However, there are a few reports of laparoscopic or laparoscopically assisted total gastrectomy performed for gastric cancer in the upper half of the stomach due to the difficulty of the surgical technique. We report the short- and long-term results for patients with gastric cancer who underwent laparoscopically assisted total gastrectomy (LATG) with lymph node dissection.

Patients and methods

Patients

From April 1998 to December 2007, 202 patients with gastric cancer underwent laparoscopically assisted gastrectomy with regional lymph node dissection in the Department of General Surgical Science at Gunma University Hospital. We studied 38 patients with upper or middle gastric cancer who had undergone total gastrectomy.

This study was not a randomized controlled study. The patients who agreed to undergo LATG constituted the LATG group, whereas those who refused LATG constituted the conventional open total gastrectomy (OTG) group. From September 1999 to December 2007, 20 patients underwent LATG, and 18 patients underwent OTG.

The indications for LATG or OTG included the following: depth of tumor invasion limited to the mucosa or submucosa, absence of lymph node metastases in preoperative examinations, and a neoplasm of any histologic type. Furthermore, LATG was indicated when the neoplasm was located in the middle or upper part of the stomach. Patients with cancer in another organ or previous abdominal laparotomy and those with cardiac, pulmonary, or hepatic insufficiency were excluded from the study.

The evaluation for the preoperative stages of gastric cancer was based on examination, including gastrointestinal endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and an upper gastrointestinal series. The diagnostic accuracy of preoperative EUS for early gastric cancer is 80% at our institution [2].

In both groups of patients, all the neoplasms were adenocarcinomas invading the mucosa or submucosa of the stomach in the preoperative examinations. Before the operations were performed, all cases were reviewed at a meeting attended by staff surgeons and anesthesiologists. Patients were informed which procedure to expect, and the possibility of conversion from laparoscopic surgery to open surgery was discussed. All patients received antithrombotic prophylaxis with low-weight heparin, elastic stockings, or both.

Surgical technique

The LATG procedure was performed as follows [7]. Laparoscopic surgery was conducted with the patient in the supine position. Carbon dioxide (CO2) pneumoperitoneum was induced after insertion of the first 12-mm cannula at the level of the umbilicus using a modified open technique. The surgeon stood to the right of the patient; the first assistant stood to the left; and the videolaparoscope operator worked from a position between the patient’s legs. Five surgical ports were inserted in the upper abdomen, and a flexible gastrointestinal fiberscope with a 120° view angle was used as a laparoscope so that a wide view could be obtained in the narrow abdominal space.

The gastrectomy began with dissection of the greater omentum using ultrasonically activated coagulating shears (LCS; Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Two retraction tubes (mini-loop retractor; Tyco Japan, Tokyo, Japan) at the antrum and gastric body were used to lift the stomach to the abdominal wall, as reported previously, and the tip of the scope was introduced into the bursa omentalis [2, 5, 7]. The dissection was continued rightward to the pylorus and included the infrapyloric lymph nodes.

The pedicles of the right gastric arteries and the right gastroepiploic artery were identified and divided with clips. The right gastric artery was separated from the hepatic artery at its origin using ultrasonically activated scissors. Lymph node dissection continued leftward along the common hepatic artery, celiac axis, left gastric artery, and proximal splenic artery. The left gastric vessels were prepared carefully and divided separately, and the artery and vein were divided with clips. The dissection of the gastrocolic ligament continued toward the spleen. The left gastroepiploic artery, posterior gastric artery, and all short gastric vessels were divided with either harmonic scissors or clips, and the lymph nodes were removed.

After dissection of the gastric and gastroepiploic vessels, the phrenoesophageal membrane and vagal nerve were divided. The first part of the duodenum was dissected adequately, then transected 2 cm below the pylorus using a 60-mm cartridge endostapler (Endo GIA, 60 mm; Autosuture, Norwalk, CT, USA). Finally, the angle of Treitz was identified, and a proper Roux-en-Y loop or jejunal loop was chosen and marked with a transfixing suture.

A longitudinal laparotomy was performed using a 6-cm skin incision at the epigastrium, and the peritoneal cavity was entered. The laparotomy wound was protected and retracted using a wound-sealing device (Lap Protector; Hakko Medical Co., Nagano, Japan). The esophagus was transected, and the entire stomach was left in the peritoneal cavity. The anvil of a circular stapler (CDH, 25 mm; Ethicon) was inserted into the esophageal stump after a cigarette suture of the esophageal stump was performed using a miniature purse-string suture device.

For 4 patients, reconstruction was performed by jejunal interposition [7]. The previously chosen jejunal loop was brought through the transverse mesocolon and out of the abdomen through the longitudinal laparotomy. A 30-cm section of the jejunum was prepared at a point 20 cm distal from the ligament of Treitz. An end-to-end jejunoduodenostomy was made using a circular stapler (CDH, 25 mm; Ethicon) introduced through the proximal stump of the interposed jejunum. The shaft of the circular stapler then was introduced into the interposed jejunum by its antimesenteric border through the proximal stump followed by an end-to-side esophagojejunostomy. The jejunal stump was closed with a 60-mm liner stapler. Next, the jejunojejunal anastomosis was completed extracorporeally.

In the remaining 16 patients, reconstruction was performed by Rou-en-Y anastomosis. A 50-cm transmesocolic Roux-en-Y loop was prepared and anastomosed side-to-end to the esophageal stump with a single application of a circular stapler (CDH, 25 mm; Ethicon). The access opening on the jejunum stump then was closed with a laparoscopic linear stapler. A side-to-side jejunojejunal anastomosis was performed at the foot of the Roux-en-Y loop with a single application of a circular stapler (CDH, 21 mm; Ethicon). Finally, the access opening on the jejunal limb was closed with the laparoscopic linear stapler device.

Total gastrectomy was performed in the usual manner through an upper midline laparotomy incision from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus. Reconstruction was performed by Roux-en-Y anastomosis in nine patients after OTG.

After the operation, the epidural tube was used for pain control and maintained until the patients no longer reported abdominal pain. The age and gender were documented, and the following demographic features were obtained from medical charts: operation time, estimated blood loss, and postoperative hospital stay. All resected stomachs were opened immediately after the operation, and dissected lymph nodes were divided according to the guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. On formalin-fixed specimens, the size, location, and gross type were measured and determined.

Follow-up evaluation

All patients were seen at the outpatient clinic once a month for 1 year, then every 3 months thereafter. The follow-up assessment consisted of a physical examination and serum CEA and CA 19-9 every 3 months and an abdominal CT scan and gastrointestinal endoscopy every 6 months until 5 years after the operation.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as means ± standard error. A statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test, the chi-square test, or the unpaired Student t-test as appropriate. All p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Survival data for 38 patients were analyzed by means of the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log rank test was used to assess the differences between prognostic factors. A statistical analysis was performed with the Stat View J-4.5 software program (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA).

Results

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the study groups are presented in Table 1. The age, sex, tumor location, gross type, histologic type, depth of wall invasion, and lymph node metastasis did not differ between the LATG and OTG groups. Tumor sizes were greater in the OTG group than in the LATG group (p = 0.04).

The perioperative data are summarized in Table 2. The operative time was 254 ± 10 min in the LATG group and 248 ± 12 min in the OTG group, whereas the blood loss was less after LATG (299 ± 50 vs 758 ± 78 ml; p < 0.01). The number of dissected lymph nodes did not differ between the LATG and OTG groups.

Postoperative hospitalization was shorter among the patients in the LATG group (19 ± 3 vs 29 ± 3 days; p < 0.05). Roux-en-Y reconstruction was more frequent in the LATG group than in the OTG group. There was no conversion from laparoscopic surgery to open surgery.

Five patients (20%) in the LATG group experienced postoperative complications including two patients with anastomotic leakage, one patient with anastomotic stenosis, and one patient each with ileus and heart failure (Table 3). One patient required reoperation after LATG for ileus. The reconstruction was performed by jejunal interposition in this case. The small bowel was incarcerated into the defect of the transverse mesocolon created by the interposed jejunum, leading to complete obstruction of the bowel.

Three patients (17%) experienced postoperative complications in the OTG group including one patient with anastomotic leakage, one patient with anastomotic stenosis requiring endoscopic dilation, and one patient with reflux esophagitis.

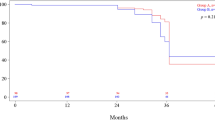

Survival analysis (Figs. 1 and 2) was available for all 38 patients (100 %). The cumulative and disease-specific 5-year survival rates for the patients who underwent LATG were 95% and 100%, respectively. The cumulative and disease-specific 5-year survival rates for the patients who underwent OTG were 90.9% and 91.7%, respectively.

One patient in the LATG group died of heart failure, and one patient was alive with peritoneal recurrence 1 year after the operation. All the other patients in the LATG group were alive and disease-free after a median follow-up period of 31 months (range, 3–60 months).

One patient in the OTG group died of gastric cancer recurrence with brain and bone metastases. All the remaining patients in the OTG group were alive and disease-free after a median follow-up period of 46 months (range, 13–60 months). There was no difference in the cumulative 5-year survival or disease-specific survival rates between the LATG and OTG groups (p = 0.81, log-rank test).

Discussion

Recently, some authors have suggested that early gastric cancer can be treated effectively with laparoscopic surgery for selected groups of patients [1, 2] However, the long-term oncologic results of laparoscopic total gastrectomy have not been determined. Our study showed that LATG could be performed safely with the intended benefits of minimally invasive surgery and oncologic adequacy. The 5-year cumulative and disease-free survival rates were not influenced by the surgical approach, confirming the radicality of the laparoscopic approach.

As in other reports, we confirmed the operative and postoperative advantages to the LATG patients (i.e., lower intraoperative blood loss and an earlier hospital discharge). These results showed that LATG for upper and middle early gastric cancer is a feasible and safe alternative to standard open gastric resection, with similar short- and long-term results that testify to the oncologic radicality of the procedure.

In our series, the operating time required for LATG did not differ from that for conventional open gastrectomy (254 vs 248 min). The average operating time for LATG reported by other researchers ranges between 183 and 407 min, and in the current study, it was 254 min, not significantly different from the mean operating time required for open surgery [8–12]. When performed by a skilled and experienced surgeon, LATG does not require any more time than OTG. Adequate training in laparoscopic technique and procedures is necessary before a surgeon embarks on LATG.

In addition, gastric resection and lymphadenectomy were performed laparoscopically. An easy anastomosis was performed via a small abdominal incision through which the resected stomach was removed in this series. To reduce the technical difficulty, we developed a device (miniature purse-string suture device) to fix the anvil to the abdominal esophagus, which was small enough (30 mm) for application to the esophagus through the small abdominal incision [13]. There was no need for conversion to open surgery, but five postoperative complications occurred. Four of five complications occurred in the first 10 cases treated and may have been related to the learning curve period.

Patients with early gastric cancer have a more favorable prognosis than patients with advanced tumors. A multicenter study showed that the 5-year survival rate for patients who underwent laparoscopically assisted gastrectomy (LAG) for early gastric cancer was as good as that for patients who underwent conventional open surgery for early gastric cancer, and that the 5-year disease-free survival rate was 93.7% for those who underwent LATG [1]. In this study, the 5-year survival rate for gastric cancer patients treated with LATG was 95%, and there was one gastric cancer recurrence in a patient with a diagnosis of advanced gastric cancer after surgery.

For a proper indication for LATG, the accuracy of the preoperative diagnosis to determine the depth of cancer invasion is critically important. For the diagnosis, we have used a combination of radiographic, endoscopic, and EUS studies. However, we could not diagnose serosal invasion of gastric cancer preoperatively due to the spread of gastric cancer cells in the proper muscle and subserosal layer. Although EUS is useful for selecting potentially eligible patients for such trials, the decision should not be based on its findings alone because the accuracy of EUS is only 72.7% for stage T4 disease [14].

In the current study, peritoneal metastasis developed in only one LATG patient, who had a T3 tumor. Peritoneal metastasis developed 1 year after the operation. A randomized clinical trial of laparoscopically assisted surgery for colorectal cancer has demonstrated that the port-site recurrence rate for laparoscopically assisted surgery is equivalent to the incisional metastasis rate for open surgery [15]. Furthermore, laparoscopic staging for gastric cancer has long been used, but reports on port-site metastasis are rare, and the incidence remains acceptable [16]. However, Lee et al. [17] reported the case of advanced gastric cancer with port-site recurrence 1 year after laparoscopic gastrectomy. The laparoscopic surgeon should be aware of peritoneal recurrence when dealing with advanced gastric cancer.

With regard to cost, one of the obstacles to the popularization of laparoscopic surgery for malignancy may be the high cost of the laparoscopic operation for a gastrointestinal malignancy. However, Adachi et al. [18] reported that laparoscopically assisted gastrectomy was less expensive than open distal gastrectomy (DG) because both the postoperative recovery period and the hospital stay were shorter. For patients who undergo gastrectomy, the additional costs of the disposable instruments can be offset by the lower charges for the ward, meals, and nursing care associated with laparoscopic gastrectomy. However, another study reported that the operation-related costs and total costs were greater for laparoscopically assisted gastrectomy than for other types of surgery [19]. These differences resulted mainly from the costs of materials used in the operating room.

Conclusion

In summary, LATG with regional lymph node dissection for upper and middle gastric cancer is considered to be a safe and useful procedure. If the patient is selected properly, LATG can be a curative and minimally invasive treatment for early gastric cancer. Nevertheless, further clinical trial observations and prospective controlled studies are needed to elucidate its long-term effects.

References

Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N (2007) A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg 245:68–72

Mochiki E, Kaniyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Asao T, Kuwano H (2005) Laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: five years experience. Surgery 137:317–322

Huscher CGS, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C (2005) Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg 241:232–237

Adachi Y, Suematsu T, Shiraishi N, Katsuta T, Morimoto A, Kitano S, Akazawa K (1999) Quality of life after laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Ann Surg 229:49–54

Mochiki E, Nakabayashi T, Kamimura H, Haga N, Asao T, Kuwano H (2002) Gastrointestinal recover and outcome after laparoscopy-assisted versus conventional open distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. World J Surg 26:1145–1149

Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Kishida S, Ogata A, Fujiwara Y, Osugi H (2007) Laparoscopic gastrectomy with regional lymph node dissection for upper gastric cancer. Br J Surg 94:204–207

Mochiki E, Kamimura H, Haga N, Asao T, Kuwano H (2002) The technique of laparoscopically assisted total gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for early gastric cancer. Surg Laparosc 16:540–544

Huscher CGS, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Brachini G, Binda B, Paola MD, Ponzano C (2007) Totally laparoscopic total and subtotal gastrectomy with extended lymph node dissection for early and advanced gastric cancer: early and long-term results of a 100-patients series. Am J Surg 194:839–844

Pugliese R, Maggioni D, Sansonna F, Scandroglio I, Ferrari GC, Di Lernia S, Costanzi A, Pauna J, de Martini P (2007) Total and subtotal laparoscopic gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Surg Endosc 21:21–27

Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Perissat J, Mahajna A (2005) Completely laparoscopic total and partial gastrectomy for benign and malignant diseases: a single institute’s prospective analysis. J Am Coll Surg 200:191–197

Omori T, Nakajima K, Endo S, Takahashi T, Hasegawa J, Nishida T (2006) Laparoscopically assisted total gastrectomy with jejuna pouch interposition. Surg Endosc 20:1497–1500

Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Kishida S, Ogata A, Fujiwara Y, Osugi H (2007) Laparoscopic gastrectomy with regional lymph node dissection for upper gastric cancer. Br J Surg 94:204–207

Asao T, Hosouchi Y, Nakabayashi T, Haga N, Mochiki E, Kuwano H (2001) Laparoscopically assisted total or distal gastrectomy with lymph node dissection for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg 88:128–132

Ganpathi IS, So JBY, Ho KY (2006) Endoscopic ultrasonography for gastric cancer: does it influence treatment? Surg Endosc 20:559–562

Davies MM, Larson DW (2004) Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: the state of the art. Surg Oncol 13:111–118

Shoup M, Brennan MF, Karpeh MS, Gillern Sm, McMahon RL, Conlon KC (2002) Port-site metastasis after diagnostic laparoscopy for upper gastrointestinal tract malignancies: an uncommon entity. Ann Surg Oncol 9:632–636

Lee YJ, Ha WS, Park ST, Choi SK Hong SC (2007) Port-site recurrence after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy: report of the first case. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 17:455–457

Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Ikebe K, Aramaki M, Bandoh T, Kitano S (2001) Evaluation of the cost for laparoscopic-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 15:932–936

Song KY, Park CH, Kang HC, Kim JJ, Park SM, Jun KH, Chin HM, Hur H (2008) Is totally laparoscopic gastrectomy less invasive than laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy? Prospective, multicenter study. J Gastrointest Surg 12:1015–1021

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mochiki, E., Toyomasu, Y., Ogata, K. et al. Laparoscopically assisted total gastrectomy with lymph node dissection for upper and middle gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 22, 1997–2002 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-0015-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-0015-9