Abstract

Dysphagia due to bony lesions of the cervical spine is rare. Almost all reported cases have been secondary to cervical osteophyte formation. We present an unusual case of a 58-year-old male who presented with dysphagia of insidious onset. Investigations revealed osteoid osteoma arising from the transverse process of the second cervical vertebra extending anteriorly in a curvilinear manner. The surgical management of this case is discussed in this report. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of dysphagia secondary to osteoid osteoma of cervical spine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A systematic review of the literature shows that dysphagia due to bony lesions of the cervical spine is caused almost exclusively by anterior osteophytic bridges associated with underlying pathology like diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) or ankylosing spondylosis [1, 2]. Other lesions include abnormal bony protuberance of anterior atlas [3]. Anterior osteophytes are responsible for almost 10% of all pharyngeal stage dysphagia in patients over 60 years of age [4].

Benign primary tumors of the spine are rare. In a review of 82 primary neoplasms of the spine over a 50-year period, McLain and Weinstein [5] reported only six benign lesions of the cervical spine. A detailed review by Bohlman et al. [6] of 23 cases of primary neoplasms of the cervical spine in adults contained only four cases of benign lesions. A meta-analysis of reviews of osteoid osteoma shows that the tumor occurs in the spine in 10%–25% of cases. The cervical spine is the second most common site following the lumbar spine and the tumor develops from the posterior elements of the spine in majority of cases [7–9].

Case Report

A 58-year-old male was seen in the outpatient department with a history of dysphagia mainly to solid food for three years; the onset was gradual. The difficulty in swallowing started as an uneasiness with taking a meal and got worse over six months before coming to our department. Over the six months before presentation, he took a longer time to finish a meal and he leaned towards boiled and soft food. There was no episode of aspiration. He denied any loss of weight. He also mentioned a lump deep in his oral cavity that has been slowly enlarging over five years. He was otherwise well with no significant past medical history.

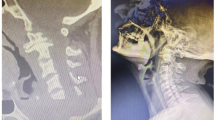

On examination he had a cone-shaped, bony, hard swelling on the right lateral wall of the oropharynx arising from behind the tonsillar fossa and extending to the midline. The swelling was 4 cm long, nontender, and completely immobile (Fig. 1). The pharyngeal mucosa over the swelling was intact. Palpation of the neck was normal. There was no additional feature on nasopharyngoscopy. Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a heterogeneous 6.5-cm bony lesion arising from the right transverse process of second cervical vertebra with a radiolucent center surrounded by sclerotic bone. It extended anterioromedially to oropharynx (Fig. 2).

An anterior cervical retropharyngeal approach was used for surgical access. The curved incision was made from the tip of the right mastoid process to the hyoid bone and continued cranially to the submental region. An additional 3-cm incision, extending vertically down from midpoint of the initial incision, was made to improve exposure. Dissection was performed to enter the retropharyngeal space while preserving the hypoglossal nerve. The longus colli muscle was elevated along with the periosteum from the anterior aspect of the arch of C1 and body of C2, taking care to avoid injury to the vertebral arteries. Further dissection allowed full exposure of the transverse process of C2. The lesion was removed using bone nibblers while keeping the oropharyngeal mucosa intact. At all times neutral head position was maintained. The wound was closed in layers.

Spinal traction and nasogastric tube feeding were used for one day postoperatively. A special diet was not required at any time before or after the operation except when the nasogastric feeding tube was used in first postoperative day because the patient was in spinal traction. The patient was discharged three days after the operation fully mobile and without any neurologic deficit. Histopathologic examination of the resected specimen showed randomly arranged interconnecting trabeculae of woven bone with lining osteoblasts and vascular loose connective tissue in between. The features were consistent with osteoid osteoma. At the followup one year after discharge, there were no postoperative complications.

Discussion

Dysphagia and swelling in the oropharynx as symptoms of osteoid osteoma has not been reported before. This case is more interesting because the tumor did not encroach on the oropharnyx directly from the cervical spine lying posteriorly; instead it originated from the laterally placed transverse process and enlarged anteromedially to cause dysphagia. In our case the dysphagia was mainly mechanical in pharyngeal phase, and extramucosal removal of the bony tumor restored swallowing to normal. The nutritional status of the patient was reasonably good before the operation, which indicates that the degree of dysphagia was not severe, rather it was uneasiness in swallowing.

The surgical options for resection of cervical spine tumors are limited. The transoral (Spezzler’s technique) results in poor exposure of the transverse process [10]. An extended maxillotomy and subtotal maxillectomy as described by Cocke et al. [10] was an option, but this was felt to be too extensive and destructive. We preferred the anterior retropharyngeal approach first described by McAfee for exposure to the transverse process of the cervical spine. The approach is entirely extramucosal allowing early return of swallowing function [10].

In summary, this is the first reported case of a skeletal benign neoplastic lesion where dysphagia is the primary presentation and thus is a rare but important differential diagnosis of pharyngeal dysphagia.

References

Ozgocmen S, Kiris A, Kocakoc E, Ardicoglu O: Osteophyte-induced dysphagia: report of three cases. Joint Bone Spine 69:226–229, 2002

Uzunca K, Birtane M, Tezel A: Dysphagia induced by a cervical osteophyte: a case report of cervical spondylosis. Chin Med J 117(3):478–480, 2004

Ilbay K, Evliyaoglu C, Etus V, Ozkarakas H, Ceylan S: Abnormal bony protuberance of anterior atlas causing dysphagia. A rare congenital anomaly. Spinal Cord 42(2):129–131, 2004

Granville LJ, Musson N, Altman R, Silverman M: Anterior cervical osteophytes as a cause of pharyngeal stage dysphagia. J Am Geriatr Soc 46(8):1003–1007, 1998

McLain RF, Weinstein JN: Tumors of the Spine. In: Herkowitz HN, Grarfin SR, Balderston RA, Eismont FJ , Bell GR, Wiesel SW (eds.) The Spine - Rothman Simeone, 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1999, pp 1176–1178 vol II, chap 38

Bohlman HH, Sachs BL, Carter JR, Riley L, Robinson RA: Primary neoplasms of cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 68:483–494, 1986

Jackson RP, Reckling FW, Mants FA: Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma : similar histologic lesions in different natural histories. Clin Orthoped 128:303–313, 1977

Keim MA, Reina EG: Osteoid osteoma as a cause of scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 57:159–163, 1975

Wood II GW: Other disorders of spine. In: Canale ST (ed.) Campbell’s Operative Orthopedics, 9th ed. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book Inc., 1998, pp 3157–3160 vol II, chap 62

Leventhal MR: Spinal anatomy and surgical approaches. In: Canale ST (ed.) Campbell’s Operative Orthopedics, 9th ed. St Louis: Mosby–Year Book Inc., 1998, , pp 2685–2690, vol III, chap 55

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Biswas, D., Mal, R.K. Dysphagia Secondary to Osteoid Osteoma of the Transverse Process of the Second Cervical Vertebra. Dysphagia 22, 73–75 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-006-9035-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-006-9035-6