Abstract

In this study, Pavlova lutheri, Chlorella vulgaris, and Porphyridium cruentum were cultured using modified F/2 media in a 1 L flask culture. Various nitrate concentrations were tested to determine an optimal nitrate concentration for algal growth. Subsequently, the effect of light emitted at a specific wavelength on biomass and lipid production by three microalgae was evaluated using various wavelengths of light-emitting diodes (LED). Biomass production by P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum were the highest with blue, red, and green LED wavelength with 1.09 g dcw/L, 1.23 g dcw/L, and 1.28 g dcw/L on day 14, respectively. Biomass production was highest at the complementary LED wavelength to the color of microalgae. Lipid production by P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum were the highest with yellow, green, and red LEDs’ wavelength, respectively. Eicosapentaenoic acid production by P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum was 10.35%, 10.14%, and 14.61%, and those of docosahexaenoic acid were 6.09%, 8.95%, and 11.29%, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Among polyunsaturated fatty acids, omega-3 fatty acid is an essential fatty acid known to be high-density lipid (HDLs), which is beneficial for human health [1]. Among them, eicosapentaenoic acid (C20H30O2, EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (C22H32O2, DHA) are essential for fetal brain development and help to prevent heart disease as well as enhance ocular health [2, 3]. DHA is also a key component of all cell membranes and is found in the brain and retina [4]. The main source of omega-3 fatty acid is fish. However, people are concerned about the intake of fish owing to concerns regarding the risk of heavy metal intake such as mercury, as well as recent reductions in global fish yields [5]. Recently, the use of alternative sources, such as microalgae, as a solution to the above-mentioned problems has been considered [6].

Microalgae are unicellular photosynthetic organisms that grow by using sun light and carbon dioxide and produce lipids that can be applied as biofuels, food, feed, and high value bioactive agents based on nutrient sources such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and gallium [7,8,9]. Microalgae grow rapidly fix carbon dioxide 10–50 times more efficiently than land plants [10,11,12]. Among different microalgal species, Pavlova lutheri, Chlorella vulgaris, and Porphyridium cruentum were used in this study. P. lutheri and C. vulgaris have a high lipid content of 30–40% per dry cell weight and are suitable for commercial use with lipids [5, 13]. In addition, P. lutheri and P. cruentum produce high content of unsaturated fatty acid and contain omega-3 fatty acids such as EPA and DHA [5].

Optimum light wavelength using light-emitting diodes (LEDs) in the narrow spectrum band is essential for microalgal culture [14]. The advantage of LEDs is low energy consumption and low heat generation with sufficient light emission to facilitate maximum growth of heat sensitive microalgae. LEDs have a longer life than fluorescent lamps and have high conversion efficiency [15]. The lifetime of LEDs is 500% and 941% longer than that of a fluorescent light. LEDs can emit uniform light to the bioreactor owing to the dispersion of lights, and microalgae can be cultured by adjusting light intensity [14].

Microalgal growth and lipid production are affected by various physical and chemical stresses as well as environmental conditions. Temperature [16], nutrients [17], light intensity [18], salt concentration [19], L/D photoperiod cycle [20], and LED wavelengths [21] affect the biomass and lipid production of microalgae. When C. vulgaris was cultured under LED light emitted at appropriate wavelengths, the biomass yields increased when light was emitted at red (660 nm) wavelength [22].

In this study, cell growth and lipid production were improved through two-phase culture system using wavelength stress. Two-phase culture system produced the highest biomass with complementary LED wavelength to the color of microalgae in the first-phase culture to produce biomass. When the cells reach the stationary phase, the culture is switched to the second-phase culture by changing the LED wavelength to similar color of microalgae as a stress to produce lipid in the unfriendly condition. In the second phase, same LED light color to microalgae was applied to produce high amount of lipid in the biomass [21].

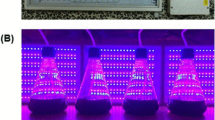

This study aimed to improve cell biomass production in the first phase and lipid production in the second phase by applying a two-phase culture system, and ultimately increase the content of unsaturated fatty acid. The first trial of culture was performed to determine optimum nitrate concentrations for the three microalgae, namely as P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum. After optimizing the nitrate concentration, the first phase of the second experiment was carried out, by employing the wavelengths of the LED light determined during the first trial, to increase cell biomass. This experiment facilitates an increase in lipid production during the second phase of culture when the microalgae could not absorb LED light stress. Therefore, when microalgae are cultured in a two-phase culture system, lipid production can be increased in the second-phase culture compared with the lipid production in the first-phase culture (Fig. 1).

Graphical views of two-phase culture system setting. LED panels with dimensions of 28.5 × 38.6 × 4.4 cm3 (Luxpia Co. Ltd., Suwon, Korea) were arranged in strips in this experiment. Each LED strip comprised 10 diodes spaced vertically and 20 diodes spaced horizontally at 1-cm intervals. The LED light panel is composed of red, yellow, green, blue, and purple. a–c first-phase cultures and d–f second-phase culture systems. a and d, b and e, and c and f are Pavlova lutheri, Chlorella vulgaris, and Porphyridium cruentum, respectively

Materials and methods

Microalgae and culture conditions

P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum were obtained from the Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology [Southern Sea Research Institute of Korean Institute of Ocean Science and Technology (KIOST), Geoje-si, Korea] and cultured under LED light emitted at various wavelengths, as shown in Fig. 2. The algae were pre-cultured for 12 days in sterilized seawater supplemented with a modified f/2 medium containing 75 mg NaNO3, 5 mg NaH2PO4·H2O, 4.36 mg Na2EDTA, 3.15 mg FeCl3·6H2O, 0.02 mg MnCl2·4H2O, 0.02 mg ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.01 mg CoCl2·6H2O, 0.01 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 0.006 mg Na2MoO4·2H2O, 30 mg Na2SiO3, 0.2 mg thiamine-HCl, 0.01 mg vitamin B12, and 0.1 mg biotin per liter [23]. The initial cell density was 1 × 105 cells/ml. The three above-mentioned strains were cultured at a temperature of 20 °C, and light intensity of 100 μmol/m2/s under a photoperiod cycle of 12:12 h L/D [21]. Sodium nitrate was used as the nitrate source [24] and concentration was evaluated at 80 mg/L, 160 mg/L, 240 mg/L, and 320 mg/L.

Photographs of microalgae cultured under different wavelengths; C. vulgaris (CV), P. lutheri (PL), and P. cruentum (PC), respectively. Cell culture was carried out under a fluorescent light as a control, b purple (400 nm), c blue (465 nm), d green (520 nm), e yellow (590 nm), and f red (625 nm) LED wavelengths

LED wavelengths for microalgal culture

LED panels with dimensions of 28.5 × 38.6 × 4.4 cm3 (Luxpia Co. Ltd., Suwon, Korea) were arranged in strips in this experiment. Each LED strip comprised 20 diodes spaced vertically and horizontally at 1-cm intervals. LED wavelengths used for the growth of microalgae were purple (400 nm), blue (465 nm), green (520 nm), yellow (590 nm), and red (625 nm). The light intensity was measured using a light sensor (TES-1339; UINS Ins., Busan, Korea) at the centerline of the flask filled with culture medium. The control culture was maintained for 17 days under fluorescent light [25].

Measurement of microalgal biomass growth

Dry cell weight was determined using an ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 6300 Pro; Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK) at an optical density of 680 nm (OD680) and 540 nm (OD540) [26, 27].

The correlation between the optical densities (680 nm and 540 nm) of the three microalgae and their dry cell weights was determined by the following equations:

.

Total lipid measurement

Cell harvesting was carried out by centrifuging (Supra R22; Hanil Scientific Inc., Gimpo, Korea) at 9946×g for 10 min and washed twice using distilled water. The cell biomass was dried using a freeze dryer (SFDSM-24L; SamWon Industry, Seoul, Korea). Subsequently, 5 mL of distilled water was added to 10 mg of the dried cell biomass, and cells were sonicated for 10 min using a sonicator (100 W, 20 kHz, 550 Sonic Dismembrator; Fisher Scientific Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The total lipid content was determined using methanol and chloroform following a modified solvent-based method [28], as shown in the following equation:

where lipid content is the cellular lipid content of the microalgae (% of DCW). W1 (g) is the weight of an empty 20-mL glass tube and W2 (g) is the weight of a 20-mL glass tube containing the extracted lipid. DCW (g) is the dried microalgal cell biomass.

Fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) measurement

The direct transesterification method [29] was used to convert extracted lipids to FAMEs. FAMEs were then analyzed using gas chromatography (GC, YL 6100; Young Lin Inc., Anyang, Korea) by employing a flame ionization detector (FID) and a silica capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.5 μm; HP-INNOWAX; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The column temperature adjustments were as follows: 140 °C for 5 min followed by a temperature increase to 240 °C at 5 °C/min, which was subsequently maintained for 10 min. The injector and FID temperatures were set at 250 °C. FAMEs were identified by comparing their retention times against those of authentic standards.

Statistical analyses

Each experiment was conducted in triplicate. The statistical significance of cell biomass and lipid content was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05) using the SPSS software (ver. 23.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Effect of nitrate concentration on cell growth

P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum were cultured in 2-L flasks with a 1-L working volume at 20 °C and at an aeration rate of 2.5 L/min. Nitrate concentration of microalgae was controlled to determine optimal biomass production. Nitrate concentrations of 80 mg/L, 160 mg/L, 240 mg/L, and 320 mg/L were prepared for cultures with a fluorescent light intensity of 100 μmol/m2/s. Figure 3a–c demonstrates that P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum cultured at nitrate concentration of 160 mg/L, 240 mg/L, and 160 mg/L showed maximum biomass production levels of 0.93 g dcw/L, 1.13 g dcw/L, and 1.25 g dcw/L, respectively, over 15 days. Increase in nitrate concentration resulted in higher cell biomass production. For the cultures of Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Dunaliella tertiolecta, and Isochrysis galbana, nitrate concentration contributing to generation of maximum biomass were different [30]. Here, P. lutheri and P. cruentum showed maximum biomass production at the same nitrate concentration of 160 mg/L, whereas the nitrate concentration required for facilitating. Maximum biomass production by C. vulgaris was different, i.e., 240 mg/L. A further increase in nitrate concentration to 160 mg/L for P. lutheri and P. cruentum led to a reduction in biomass production levels; C. vulgaris also showed the same trend for nitrate concentration exceeding 240 mg/L, as shown in Fig. 3a–c. This indicates that high concentrations of nitrate have an inhibitory effect on algal growth. Microalgae increase the activity of nitrate reductase at high concentrations of nitrate, leading to an enhanced production of nitrite and ammonia; thus, the accumulated nitrite and ammonia may act as inhibitory compounds in biomass production [31, 32].

Effects of LED wavelengths on cell growth and lipid accumulation in the first phase of culture

Figure 4 show the complementary LED wavelengths. Complementary wavelengths are wavelengths that emit white light when two wavelengths of lights are mixed. The wavelength at the opposite position of the color wheel is called the complementary wavelength [33].

An important factor in determining the optimal photosynthetic activity of microalgae is the wavelength. Cell growth and lipid production in microalgae are affected by LED wavelengths. The LED lights were emitted at the following wavelengths: purple (400 nm), blue (465 nm), green (520 nm), yellow (590 nm), and red (625 nm). Fluorescent light was used for the control culture.

Figure 5 shows dry cell weight achieved using the purple (400 nm) to red (625 nm) wavelengths at optimal nitrate concentrations of 160 mg/L for P. lutheri and P. cruentum, and 240 mg/L nitrate for C. vulgaris. Figure 4a shows that, among these wavelengths, blue LED wavelength facilitated P. lutheri to produce the highest biomass of 1.09 g dcw/L on day 14, followed by purple LED (0.99 g dcw/L), red LED (0.98 g dcw/L), fluorescent light (0.89 g dcw/L), green LED (0.86 g dcw/L), and yellow LED (0.62 g dcw/L). These results indicated that the use of blue LED wavelength as a light source could enhance the biomass production by P. lutheri. Phaeodactylum tricornutum, a brown-colored microalgae similar to P. lutheri, showed the highest biomass production under blue LED [34]. This is because P. tricornutum possesses chlorophyll a, chlorophyll c1 + c2, and fucoxanthin as primary pigments and some carotenoids that absorb blue light [35]. Thus, for P. lutheri, blue LED wavelength was chosen as the wavelength for biomass production in the first phase of culture.

Figure 5b shows that C. vulgaris produced maximum biomass at 1.23 g dcw/L on day 14 under red LED wavelength, followed by blue LED (1.15 g dcw/L), fluorescent light (1.10 g dcw/L), purple LED (1.06 g dcw/L), yellow LED (1.04 g dcw/L), and green LED (0.88 g dcw/L). Therefore, red LED wavelength was used to increase the biomass production of C. vulgaris. This result is consistent with that reported [22]. When C. vulgaris was cultured at various wavelengths of red, white, yellow, purple, blue, and green LEDs, C. vulgaris generated the highest biomass under red LED. The reason for this is that, C. vulgaris, green microalgae, possesses chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and the accessory pigment carotenoid for photosynthesis, and that all chlorophylls have a maximum absorption band at red (600–700 nm) and blue (400–500 nm) wavelengths [36]. Thus, red LED wavelength was a suitable wavelength for biomass production of C. vulgaris in the first phase of culture.

Figure 5c shows that P. cruentum yielded the highest biomass at 1.28 g dcw/L under green LED wavelength, following by purple LED (1.23 g dcw/L), blue LED (1.23 g dcw/L), fluorescent light (1.22 g dcw/L), yellow LED (1.20 g dcw/L), and red LED (1.17 g dcw/L). Similar biomass production levels were also achieved by Porphyridium purpureum at the above-mentioned wavelengths [37]. P. purpureum is a red microalga belonging to the same genus as P. cruentum. P. purpureum showed the highest biomass production under green LED among red, green, and blue wavelengths as well as on being exposed to a combination of red, green, and blue. According to these results, P. cruentum was cultured for increasing biomass production at green LED wavelengths. Phycobiliprotein has been reported to be a major harvest pigment of red microalgae. Phycobiliprotein is mainly composed of phycoerythrin and small amounts of phycocyanin and allophycocyanin [38]. Phycoerythrin absorbs light efficiently at green wavelength with a range of absorption bands of 450–600 nm [37]. Thus, green LED wavelength was selected as a suitable wavelength for biomass production of P. cruentum in the first phase of culture.

The main carotenoids of microalgae with various LED wavelength produced different amounts of biomass. The supply of undesired wavelengths to carotenoids caused in photo-oxidation, reduction of photosynthesis, and decrease of cell division leading to a reduction of biomass production [39]. However, proper light with desired wavelengths to main carotenoids of microalgae increases the activity of cell and biomass production [40].

According to the results of Fig. 5, the brown microalgae P. lutheri, the green microalgae C. vulgaris, and the red microalgae P. cruentum generate the highest biomass yields in complementary LED wavelength to the microalgae color blue (465 nm), red (625 nm), and green (520 nm) LEDs, respectively. This indicates that the microalgae were able to increase absorption of light at complementary LED wavelengths.

Figure 6 shows the lipid content on day 14 of the first phase of culture. P. lutheri showed the highest lipid content at 52.0% (w/w) under yellow wavelength as the same wavelength of the cell color. C. vulgaris showed the highest lipid content at 50.5% (w/w) under green LED wavelength. P. cruentum showed the highest lipid content at 36.7% (w/w) under red LED wavelength. The highest lipid production can be obtained at the wavelength that generates the lowest biomass. Lipid production is occurred by protein and carotenoid biodegradation. As a result, photosynthesis does not occur and the biomass production is low [41]. Microalgae accumulate lipids under stress condition, because they reflect light without absorbing it [30]. Lipid accumulation is induced by energy imbalance of microalgae and the exposure to stress factor. In addition, cells produced lipid from self-defense mechanisms by photo-oxidation of light [42]. The lipid production was carried out by the enzymatic synthesis of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBPCase) and carbonic anhydrase [43]. Thus, yellow, green, and red LEDs were selected as optimal wavelengths for lipid production in the second phase of culture of P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum, respectively.

Biomass and lipid production by two-phase culture

The two-phase cultures of microalgae were carried out under optimal nitrate concentrations and LED wavelengths, as shown in Fig. 7.

Microalgal culture under blue, red, and green LED wavelengths for biomass production and under yellow, green, and red LED wavelengths for lipid production by P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum, respectively. a Two-phase cultures of P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum involving biomass production in the first phase and lipid production in the second phase and b lipid production by the three microalgae under LED wavelength-induced stress at the stationary phase of the second phase of culture. The vertical line in (a) indicates the start of the second phase of the cultures. Different letters indicate significant differences in lipid content (P < 0.05, Duncan’s test)

Figure 7a shows the two-phase culture for biomass and lipid production by P. lutheri. P. lutheri used blue (465 nm) LED wavelength in the first phase of culture for biomass production and yellow (590 nm) LED wavelength in the second phase of culture for lipid production. The second phase of culture was started on day 14. Red (625 nm) LED wavelength was used for the first phase of culture of C. vulgaris for biomass production and green (520 nm) LED wavelength was used for the second phase of culture for lipid production. Green (520 nm) LED wavelength was used for biomass production by P. cruentum in the first phase of culture, while red (625 nm) LED wavelength was used in the second phase for lipid production.

LED light stress in the second phase of culture was exerted for 3 days to determine the optimum culture time to obtain maximum lipid content. The lipid content of P. lutheri cultured in two-phase culture is shown in Fig. 7b. On day 2 of the second phase of culture, P. lutheri generated the highest lipid content at 49.1% under yellow LED, while C. vulgaris and P. cruentum generated the highest lipid content at 46.2% and 37.8% under green and red LED wavelengths, respectively. Under stress-induced conditions, lipid content was highest on day 2 and slightly decreased on day 3. Day 3 is associated with excessive and prolonged stresses that decrease lipid production. Stress is required to generate high lipid content. However, the duration of light exposure increases, the lipid production decreases due to oxidative stress [44]. Similar results were reported regarding the effect of green wavelength stress on lipid synthesis in Nannochloropsis oculata, Nannochloropsis salina, and Nannochloropsis oceanica [21]. The results revealed that lipid production could be improved in the second phase of culture when LED light under stress-induced condition was employed in the two-phase culture. According to these results, the above-mentioned condition is critical to increase lipid production in the two-phase culture.

Effect of LED wavelengths on fatty acid composition in lipids produced from three microalgae

Table 1 presents fatty acid composition of P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum cultures. Table 1 (A) shows the fatty acid composition at the end of the first phase of culture, and Table 1 (B) shows the fatty acid composition on day 2 of the second phase of culture. As shown in Table 1 (A), all three microalgae contain the highest stearic (C18:0) acid content, ranging from 34.25% (w/w) to 43.77% (w/w) for P. lutheri; 47.26% (w/w) to 63.47% (w/w), C. vulgaris; and 45.64% (w/w) to 56.76% (w/w), P. cruentum. The most common components of biodiesels are palmitic acid (C16:0), palmitoleic acid (C16:1), stearic acid (C18:0), oleic acid (C18:1), and linoleic acid (C18:2) methyl esters [45]. Stearic acid (C18:0) could be used as a biodiesel because of its high cetane number [46]. As shown in Table 1 (B), the content of unsaturated fatty acids in the three microalgae after the second phase of culture was higher than that in the first phase of culture. In the second phase of culture, the highest unsaturated fatty acid content of P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum was determined to be 55.64% (w/w), 45.91% (w/w), and 43.38% (w/w) on being exposed to yellow, green, and red LED wavelengths, respectively. This suggests that unsaturated fatty acid content was increased under stress-induced by wavelength radiation during the second phase of culture.

Conclusion

Microalgal culture using two-phase culture system increases biomass and lipid production. In the first phase, the growth of P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum was increased by selecting the complementary LED wavelength of microalgae colors, blue (465 nm), red (625 nm), and green (520 nm), respectively. The lipid content was increased in the second phase of culture. P. lutheri, C. vulgaris, and P. cruentum produced 31.3% (w/w), 29.0% (w/w), and 25.8% (w/w) of unsaturated fatty acids in the first phase, which increased to 42.7% (w/w), 35.2% (w/w), and 32.5% (w/w) during the second phase by exposing microalgae to the same color LED wavelength as a stress condition, respectively.

References

Su KP, Huang SY, Chiu TH, Huang KC, Huang CL, Chang HC, Pariante CM (2008) Focus on women’s mental health omega-3 fatty acids for major depressive disorder during pregnancy: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 69:644–651

Wen ZY, Chen F (2003) Heterotrophic production of eicosapentaenoic acid by microalgae. Biotechnol Adv 21:273–294

Dunstan JA, Mitoulas LR, Dixon G, Doherty DA, Hartmann PE, Simmer K, Prescott SL (2007) The effects of fish oil supplementation in pregnancy on breast milk fatty acid composition over the course of lactation: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Res 62:689–694

Swanson D, Block R, Mousa SA (2012) Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: health benefits throughout life. Adv Nutr 3:1–7

Ryckebosch E, Bruneel C, Termote-Verhalle R, Goiris K, Muylaert K, Foubert I (2014) Nutritional evaluation of microalgae oils rich in omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids as an alternative for fish oil. Food Chem 160:393–400

Sirisuk P, Sunwoo I, Kim SH, Awah CC, Ra CH, Kim JM, Jeong GT, Kim SK (2018) Enhancement of biomass, lipids, and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) production in Nannochloropsis oceanica with a combination of single wavelength light emitting diodes (LEDs) and low temperature in a three-phase culture system. Bioresour Technol 270:504–511

Hoekman SK, Broch A, Robbins C, Ceniceros E, Natarajan M (2012) Review of biodiesel composition, properties, and specifications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 16:143–169

Wu W, Wang PH, Lee DJ, Chang JS (2017) Global optimization of microalgae-to-biodiesel chains with integrated cogasification combined cycle systems based on greenhouse gas emissions reductions. Appl Energy 197:63–82

Shimizu Y (1996) Microalgal: a new perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol 50:431–465

Tredici MR (2010) Photobiology of microalgae mass cultures: understanding the tools for the next green revolution. Biofuels 1:143–162

Li Y, Horsman M, Wu N, Lan CQ, Dubois-Calero N (2008) Biofuels from microalgae. Biotechnol Prog 24:815–820

Lam MK, Lee KT, Mohamed AR (2012) Current status and challenges on microalgae-based carbon capture. Int J Greenh Gas Control 10:456–469

Liang Y, Sarkany N, Cui Y (2009) Biomass and lipid productivities of Chlorella vulgaris under autotrophic, heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth conditions. Biotechnol Lett 31:1043–1049

Teo CL, Atta M, Bukhari A, Taisir M, Yusuf AM, Idris A (2014) Enhancing growth and lipid production of marine microalgae for biodiesel production via the use of different LED wavelengths. Bioresour Technol 162:38–44

Chen W, Sommerfeld M, Hu Q (2011) Microwave-assisted Nile red method for in vivo quantification of neutral lipids in microalgae. Bioresour Technol 102:135–141

Renaud SM, Thinh L-V, Lambrinidis G, Parry DL (2002) Effect of temperature on growth, chemical composition and fatty acid composition of tropical Australian microalgae grown in batch cultures. Aquaculture 211:195–214

Yang J, Xu M, Zhang X, Hu Q, Sommerfeld M, Chen Y (2011) Life-cycle analysis on biodiesel production from microalgae: water footprint and nutrients balance. Bioresour Technol 102:159–165

Cheirsilp B, Torpee S (2012) Enhanced growth and lipid production of microalgae under mixotrophic culture condition: effect of light intensity, glucose concentration and fed-batch cultivation. Bioresour Technol 110:510–516

Takagi M, Karseno Yoshida T (2006) Effect of salt concentration on intracellular accumulation of lipids and triacylglyceride in marine microalgae Dunaliella cells. J Biosci Bioeng 101:223–226

Wahidin S, Idris A, Shaleh SRM (2013) The influence of light intensity and photoperiod on the growth and lipid content of microalgae Nannochloropsis sp. Bioresour Technol 129:7–11

Ra CH, Kang CH, Jung JH, Jeong GT, Kim SK (2016) Effects of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on the accumulation of lipid content using a two-phase culture process with three microalgae. Bioresour Technol 212:254–261

Yan C, Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Luo X (2013) Effects of various LED light wavelengths and light intensity supply strategies on synthetic high-strength wastewater purification by Chlorella vulgaris. Biodegradation 24:721–732

Guillard RRL, Ryther JH (1962) Studies of marine planktonic diatoms: I. Cyclotella nana hustedt, and detonula confervacea (cleve) gran. Can J Microbiol 8:229–239

Lananan F, Jusoh A, Ali N, Lam SS, Endut A (2013) Effect of conway medium and f/2 medium on the growth of six genera of South China Sea marine microalgae. Bioresour Technol 141:75–82

Borowitzka MA (1999) Commercial production of microalgae: ponds, tanks, and fermenters. Prog Ind Microbiol 35:313–321

Collos Y, Mornet F, Sciandra A, Waser N, Larson A, Harrison PJ (1999) An optical method for the rapid measurement of micromolar concentrations of nitrate in marine phytoplankton cultures. J Appl Phycol 11:179–184

Maksimova IV, Matorin DN, Plekhanov SE, Vladimirova MG, Volgin SL, Maslova IP (2000) Optimization of maintenance conditions for some microforms of red algae in collections. Russ J Plant Physiol 47:779–785

Bligh EG, Dyer WJ (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Biochem Physiol 37:911–917

Dhup S, Dhawan V (2014) Effect of nitrogen concentration on lipid productivity and fatty acid composition of Monoraphidium sp. Bioresour Technol 152:572–575

Jung JH, Sirisuk P, Ra CH, Kim JM, Jeong GT, Kim SK (2019) Effects of green LED light and three stresses on biomass and lipid accumulation with two-phase culture of microalgae. Process Biochem 77:93–99

Jeanfils J, Canisius M-F, Burlion N (1993) Effect of high nitrate concentrations on growth and nitrate uptake by free-living and immobilized Chlorella vulgaris cells. J Appl Phycol 5:369–374

Ra CH, Kang CH, Jung JH, Jeong GT, Kim SK (2016) Enhanced biomass production and lipid accumulation of Picochlorum atomus using light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Bioresour Technol 218:1279–1283

Bruno T, Svoronos P, Svoronos PDN (2005) CRC handbook of fundamental spectroscopic correlation charts. CRC Press, Cambridge

Costa B, Jungandreas A, Jakob T, Weisheit W, Mittag M, Wilhelm C (2013) Blue light is essential for high light acclimation and photoprotection in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J Exp Bot 64:483–493

Kosakowska A, Lewandowska J, Stoń J, Burkiewicz K (2004) Qualitative and quantitative composition of pigments in Phaeodactylum tricornutum (Bacillariophyceae) stressed by iron. Biometals 17:45–52

Kubín Š, Borns E, Doucha J, Seiss U (1983) Light absorption and production rate of Chlorella vulgaris in light of different spectral composition. Biochem und Physiol der Pflanz 178:193–205

Coward T, Fuentes-Grünewald C, Silkina A, Oatley-Radcliffe DL, Llewellyn G, Lovitt RW (2016) Utilising light-emitting diodes of specific narrow wavelengths for the optimization and co-production of multiple high-value compounds in Porphyridium purpureum. Bioresour Technol 221:607–615

Guihéneuf F, Stengel DB (2015) Towards the biorefinery concept: interaction of light, temperature and nitrogen for optimizing the co-production of high-value compounds in Porphyridium purpureum. Algal Res 10:152–163

Severes A, Hegde S, D’Souza L, Hegde S (2017) Use of light emitting diodes (LEDs) for enhanced lipid production in micro-algae based biofuels. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 170:235–240

Duarte JH, de Souza CO, Druzian JI, Costa JAV (2019) Light emitting diodes applied in Synechococcus nidulans cultures: effect on growth, pigments production and lipid profiles. Bioresour Technol 280:511–514

Chen B, Wan C, Mehmood MA, Chang JS, Bai F, Zhao X (2017) Manipulating environmental stresses and stress tolerance of microalgae for enhanced production of lipids and value-added products–A review. Bioresour Technol 244:1198–1206

Shin YS, Il Choi H, Choi JW, Lee JS, Sung YJ, Sim SJ (2018) Multilateral approach on enhancing economic viability of lipid production from microalgae: a review. Bioresour Technol 258:335–344

Roscher E, Zetsche K (1986) The effects of light quality and intensity on the synthesis of ribulose-l,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and its mRNAs in the green alga Chlorogonium elongatum. Planta 167:582–586

Lucas-Salas LM, Castrillo M, Martínez D (2013) Effects of dilution rate and water reuse on biomass and lipid production of Scenedesmus obliquus in a two-stage novel photobioreactor. Bioresour Technol 143:344–352

Ramos MJ, Fernández CM, Casas A, Rodriguez L, Pérez Á (2009) Influence of fatty acid composition of raw materials on biodiesel properties. Bioresour Technol 100:261–268

Knothe G, Matheaus AC, Ryan TW (2003) Cetane numbers of branched and straight-chain fatty esters determined in an ignition quality tester. Fuel 82:971–975

Acknowledgements

This research was a part of the project titled ‘Innovative marine production technology driven by LED-ICT convergence photo-biology (D11506419H480000110)’, funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.H., Sunwoo, I.Y., Hong, H.J. et al. Lipid and unsaturated fatty acid productions from three microalgae using nitrate and light-emitting diodes with complementary LED wavelength in a two-phase culture system. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 42, 1517–1526 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-019-02149-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-019-02149-y