Abstract

Purpose

We compared laparoscopic approach with the conventional laparotomy approach for the treatment of patients with endometrial carcinoma in developing country.

Methods

Two hundred and seventy-two patients with endometrial carcinoma were enrolled in a prospective randomized trial and treated with laparoscopic or laparotomy approach.

Results

One hundred and fifty-one patients were treated by laparoscopy, while one hundred and twenty-one patients were treated by laparotomy. The median operative time was 211 min in the laparoscopy group and 231 min in the laparotomy group (P > 0.05). The median blood loss was 86 ml in the laparoscopy group and 419 ml in the laparotomy group (P < 0.05). The median length of hospital stay was 3 days in the laparoscopy group and 6 days in the laparotomy group (P < 0.05). Pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed in all the patients. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed in 15 % of the laparoscopy and 31.4 % of laparotomy group (P < 0.05). The overall survival and 5-year survival rate for the TLH were 94 and 96 % compared with 90.1 and 91 % in the TAH, respectively (P > 0.05).

Conclusions

Laparoscopic surgery is a safe and reliable alternative to laparotomy in the management of endometrial carcinoma patients, with significantly reduced hospital stay and postoperative complications; however, it does not seem to improve the overall survival and 5-year survival rate, although multicenter randomized trials are required to evaluate the overall oncologic outcomes of this procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is the most common gynecologic oncology in the United States and European countries (Jemal et al. 2006), and its incidence is increasing in developing countries because of lengthening of life span and improving quality of life. The common symptom of EC is postmenopausal uterine bleeding; then, the majority of patients are diagnosed at early stage of EC (Creasman et al. 2006). In such patients, the staging surgery is the standard treatment. The staging surgery includes peritoneal washings, total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and/or para-aortic lymphadenectomy (ACOG Practice Bulletin 2005). Traditionally, the staging surgery has been performed via a midline vertical incision. However, many patients with EC present with comorbidity such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, and abdominal surgery is associated with increased risk of complications (Salani et al. 2009; Eltabbakh et al. 2000). In recent years, with the fast growing availability of laparoscopy, laparoscopic surgery has made it increasingly attractive as an alternative to laparotomy approach. Recently, several authors reported the feasibility and safety of the laparoscopic approach in early-stage EC compared with laparotomy approach (Mourits et al. 2010; Cho et al. 2007; Walker et al. 2009). However, data related to recurrence rate and long-term survival are limited and results from prospective or randomized studies are even less available. The purpose of this prospective randomized study was to confirm the feasibility and safety of the laparoscopy procedure, in the treatment of EC as well as to report our long-term recurrence rate and overall survival rate.

Materials and methods

From January 2000 to December 2010, 318 consecutive patients were referred to the Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital affiliated Capital Medical University to be treated for histologically confirmed EC. All patients were considered to be candidates for a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic with laparotomy approach treatment. All records were kept prospectively in a computerized database. Randomization was performed by means of a central managed random number table.

All patients entered into the study had their initial pathologic diagnosis confirmed at our department. Exclusion criteria for the two groups were ovarian lesions, contraindications for general anesthesia, systemic infections, a bulky uterus ≥12 weeks size, and documented significant cardiopulmonary disease. All the patients who underwent laparoscopic approach were informed that conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy was expected in case of intraoperative complications or other difficulties. All patients and their spouses were comprehensively counseled about the benefits and potential risk of each approach. The staging of the patients was done according to the FIGO 1988 staging system.

Preoperative workup consisted of pelvic examination, vaginal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, chest X-ray, and blood sampling. Tumor type was defined based on the preoperative endometrial biopsy, while depth of myometrial infiltration was based on the frozen section. Pelvic lymphadenectomy and para-aortic lymph nodes sampling were performed in all the patients. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy up to the level of the inferior mesenteric artery was performed in patients with positive pelvic lymph node discovered at frozen section evaluation and non-endometrioid carcinomas. In histologically proved tumor infiltration of the endocervix, radical hysterectomy with pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection was performed. Infracolic omentectomy was performed in serous and clear cell endometrial carcinoma. All patients had antibiotic prophylaxis (cefoxitin sodium 2 g intravenously) half an hour before the operation. Intra-operative lower extremity sequential compression devices and graduated compression stocking for venous thrombosis prophylaxis were used. After the operation, low molecular weight enoxaparin was used.

After operation, stage IaG1-G2 and IbG1-G2 patients did not receive postoperative adjuvant treatment, and vaginal cuff brachytherapy or chemotherapy was recommended in other patients, and patients with lymph node metastases received pelvic irradiation. Patients with serous or clear cell cancer received 3–6 cycles of chemotherapy. Recurrences were classified by the site of the first recurrence. The overall survival was calculated from the date of the endometrial carcinoma diagnosis to death from any cause.

The patients characteristics included age, BMI, FIGO surgical stage, histological type and grade, number of lymph nodes yielded, postoperative hospital stay, operating time, estimated blood loss, need for blood transfusion, complications, duration of follow-up, and development of disease recurrence of death.

Information regarding patients was obtained from the hospital records, physicians, and direct reports from the patients. We confirmed information and status on patients by direct telephone interviews. Follow-up evaluations were scheduled 1 month after operation, and then every 3 months for the first 2 year, and every 4 months for the next 2 year, and every 6 months thereafter. The median duration of follow-up was 68 (range 2–153) months.

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistic software version 19.0 (SPSS version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The independent sample t test was used for comparison of median, and the χ 2 test was used for comparison of proportions. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant for all tests. The BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Survival data were estimated using Kaplan–Meier curves.

Results

Three hundred and eighteen patients with endometrial carcinoma were reviewed in the study and 272 patients met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-five patients with severe cardiopulmonary disease or contraindications of general anesthesia, five patients with bladder or rectum metastasis detected by MRI, and six patients with larger uterine were excluded from the study. One hundred and fifty-one patients were finally treated successfully by laparoscopy, while 121 patients were treated with laparotomy. Age and BMI were similar in the two groups; likewise, no significant differences were found regarding histology type, grading, tumor stage, and lymph node status; all the patients with atypical histology were equally distributed in the two groups. Various patient characteristics are shown in the Table 1. Operative data are summarized in Table 2.

The operating time was 211 min (range 100–460 min) in the laparoscopy group and 261 min (range 90–570 min) in the laparotomy group (P < 0.01). The median blood loss was 86 ml (range 5–450 ml) in the laparoscopy group and 419 ml (range 20–4,000 ml) in the laparotomy group. No women in the laparoscopy group needed blood transfusion, while four patients in the laparotomy group had intra-operative or postoperative transfusion. The median length of hospital stay was 3 days in laparoscopy group and 6 days in laparotomy group (P < 0.01). Seven patients in laparoscopy group did not undergo para-aortic lymph nodes sampling because of Trendelenburg position no longer tolerated, and five patients in laparotomy group did not undergo sampling because of pelvic adhesion after many abdominal operation history. The two groups with a similar mean number of lymph nodes were obtained (25 vs 23). Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed in 23 patients of the laparoscopy group and in 38 patients of the laparotomy group.

After a median duration of follow-up of 68 (range 2–153) months, the total recurrence rate was 4.7 % (n = 13). Seven (4.6 %) of 151 patients of the laparoscopy group had a recurrence versus 6 (5.0 %) of 121 patients of the laparotomy group. Four recurrences were observed in patients of laparoscopic at peritoneal and liver and three recurrences at vaginal vault, but none of those were in the laparoscopy port sites. Three recurrences patients of laparotomy group at abdominal incision, and another three recurrences at peritoneal and liver. There was no difference in the rate of recurrence or survival between the different approaches. Recurrent disease was treated with radiotherapy or combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Twenty-one patients (7.7 %) died, 9 (6.0 %) assigned to laparoscopy group and 12 (9.9 %) to laparotomy group. 15 of these 21 patients died from intercurrent disease, 6 of the laparoscopy group and 9 of the laparotomy group. 6 patients died from EC: 3 in the laparoscopy group and 3 in the laparotomy group.

The 5-year overall survival rates were 91 % of laparotomy and 96 % of laparoscopy, respectively. The overall survival of laparotomy was 90.1 %, and laparoscopy was 94.0 % (P = 0.418).

Discussion

The surgical management for EC is highly variable and is currently under investigation. In 1992, Childers and Surwit published the first report describing the management of EC using laparoscopy (Childers and Surwit 1992). Total laparoscopic approach is defined as all the procedures performed entirely by laparoscopy, and the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and removed lymph nodes were subsequently removed through vagina. The vaginal cuff is sutured laparoscopically as well, thus avoiding the need for a vaginal procedure. The procedure has some advantages over the laparoscopy-assisted procedure; it avoids the time loss necessary to shift from the laparoscopic to the vaginal approach, and it permits an easy removal of the uterus and adnexa, even in a fixed uterus and with a narrow vagina (Seracchioli et al. 2005).

Our data indicate that both laparoscopic and laparotomy approaches are feasible in patients with EC but that laparoscopy may have more advantages than laparotomy in operative blood loss, days of hospitalization, and complication rate. Our data confirmed that a longer operative time is needed for laparotomy staging surgery compared with laparoscopic approach; however, the difference between the two approaches seems no statistically and clinically significant with a median difference of about 20 min. A significant reduction in blood loss in patients who received laparoscopy was reported. Duration of hospital stay after laparoscopic approach ranged from 2 to 8.5 days. All previous studies showed significantly shorter hospitalization with laparoscopy compared with laparotomy (Palomba et al. 2009). We found a median duration of hospital stay after laparotomy of 6 days compared with 3 days after laparoscopy. Similar results were demonstrated in other Asian countries studies (Cho et al. 2007). Generally speaking, hospital stays following laparoscopy are longer in China than in other western hospitals. Because of the insurance coverage for cancer patients in our country, most cancer patients want to stay in the hospital as long as possible. Shortly, the longer hospital stays following laparoscopy are due to our country’s medical insurance system.

In this present study, we demonstrated that laparoscopic surgery is safer than abdominal surgery for the treatment of patients with EC. In our study, the complication rate in laparoscopy group was 8.6 %. According to our data, there was significant difference between the two groups, as the complication rate in laparotomy was 28.1 %. LAP-2, which is a large prospective randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopy (n = 1,696) to laparotomy (n = 920) for endometrial cancer staging, reported 8 % intraoperative complications for the laparoscopy versus 10 % for the laparotomy group, and 14 versus 21 % postoperative complications (Walker et al. 2009). According to the chest physicians, 40–80 % of cancer patients undergoing surgery without thromboprophylaxis develop calf vein thrombosis, 10–20 % a proximal DVT, and 1–5 % a fatal pulmonary embolism (Clagett et al. 1998). The patients with endometrial carcinoma often have other medical problems such as diabetes, hypertension, and longer duration of immobilization after surgery in laparotomy group may have been due to the high-risk factors of DVT and pulmonary embolism. In our department, we are doing a research about the prophylaxis of DVT after pelvic surgery. We provide graduated compression stocking and intermittent pneumatic compression during the operation and low molecular weight heparins after the operation to the high-risk patients. The therapeutic combination of graduated compression stocking and intermittent pneumatic compression was effective for DVT prevention in patients undergoing pelvic surgery (Jie 2012). Therefore, in our present study, the incidence of thromboembolic disease (pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis) is lower than other reports (Table 3).

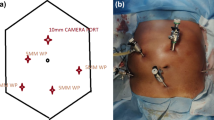

Another common postoperative complication is lymph cysts. Although most of the patients with lymph cysts had no symptom, we prescribed external application of the traditional Chinese medicines Rheumpalmatum and Mirabilite to treat the lymph cysts, and the lymph cysts could be almost reduced by this method. It is inevitable to make the patients panic. The literature reported that the risk of developing lymph cysts may increase with the number of lymph nodes removed, and another reported that patients who underwent lymphadenectomy had higher rates of lymph cysts when compared with those who underwent only lymph node sampling (Abu-Rustum et al. 2006; Todo et al. 2010; Nunns et al. 2000). In the present study, we found a trend toward increased lymph cysts after laparoscopic approach; however, regarding the number of nodes removed, the amount of pelvic nodes dissected during laparoscopy was similar to those excised during laparotomy. It follows that, the number of lymph nodes removed is not the only reason for the formation of lymph cysts; it may be related with the operative time, the skill of operation and so on (Fig. 1).

The role of lymphadenectomy in EC is currently controversial. Although the status of lymph node provides prognostic information highly useful in determining the need for and design of an appropriate adjuvant therapy program, the therapeutic value of lymphadenectomy is still not clear. Some therapeutic values of lymphadenectomy are based on retrospective studies that reported a significant survival advantage for patients undergoing lymphadenectomy (Chan et al. 2006; Todo et al. 2010). However, recently two randomized trials have demonstrated that there is no value in performing lymphadenectomy for clinical stage I EC in terms of overall, disease-specific, and recurrence-free survival (ASTEC Study Group 2009; Benedetti et al. 2008). The accumulated evidence suggested that lymphadenectomy is not appropriate for low-risk patients (May et al. 2010). The policy in our study is that pelvic lymphadenectomy and para-aortic lymph nodes sampling were performed in all the patients. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed in patients with positive pelvic lymph node discovered at frozen section evaluation and non-endometrioid carcinomas. The para-aortic node lymphadenectomy was performed only when pelvic lymph nodes were positive by frozen section or other risk factors associated with a poor prognosis and the possiblity of para-aortic lymph node metastasis (Morrow et al. 1991). This was recently confirmed by two papers, which demonstrated that the risk of para-aortic metastasis was approximately 1 %, even in high-risk tumors (Abu-Rustum et al. 2009; Chiang 2011). In contrast, a large Japanese retrospective study of endometrial cancer patients staged with either pelvic lymphadenectomy or para-aortic lymphadenectomy (to the level of the renal vessels) demonstrated that overall survival was significantly improved in those who underwent more comprehensive staging (Todo et al. 2010). Therefore, the most rational approach is to adapt the indication of lymphadenectomy according to the characteristics of patients and tumors biopsy or frozen section.

The median follow-up of 68 months for the laparoscopy and laparotomy groups exceeds the period in which more than 80 % of local or distant recurrences develop (DiSaia et al. 1985). Port-site recurrence following laparoscopy in patients with endometrial carcinoma has been reported (Muntz et al. 1999). No port-site metastases were observed in laparoscopy group of our study. All removed tissue was retrieved in a pipe through vagina to avoid contact with the vaginal wall, and the vagina was thoroughly irrigated before suturing. In addition to trocar placement, some surgeon may use an intrauterine manipulator for laparoscopic procedure. The uterine manipulator is essential to improve exposure and prevent ureteral complications. This has increased concerns regarding the dissemination of malignant cells to the vaginal cuff and the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes. It was claimed that the fallopian tubes should be coagulated or occluded at the beginning of the procedure (Holland et al. 2004). The finding that peritoneal washings before and after the insertion of the uterine manipulator were identical indicated that uterine manipulation at the time of laparoscopic hysterectomy does not increase the incidence of positive peritoneal cytology among women with EC (Eltabbakh and Mount 2006). In our study, we use a uterine manipulator in all patients with coagulation of the fallopian tubes being the first step after peritoneal washing. At the end of the operation, we irrigated the pelvic cavity by injecting sterile water with 16 mg mitomycin in order to reduce the recurrence of pelvic effectively.

To be accepted as the standard treatment for carcinoma, it becomes mandatory not to compromise standard survival outcomes. Most of the studies that described the survival of women with EC after laparoscopic approach in comparison with laparotomy are retrospective study except for limited prospective studies (Malur et al. 2001; Tozzi et al. 2005; Kalogiannidis et al. 2007; Malzoni et al. 2009) (see Table 4). In agreement with our study, there were no significant differences in survival analyses based on surgical management approaches. The overall survival of our patients treated by laparoscopic approach was 94 %, which was not significantly different from the 90.1 % obtained by laparotomy. 5-year survival rate was also comparable (laparoscopy 96 % vs laparotomy 91 %). Magrina et al. (1999), from Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, in clinical stage I population (n = 56) treated by laparoscopic lymphadenectomy with vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy, showed 3-year overall survival and cause-specific survival 75.8 and 87.4 %, respectively. Eltabbakh reported in 100 clinical stage I patients with endometrial adenocarcinoma undergoing LAVH (median follow-up 27 months) an estimated 5-year overall survival of 96 % (Eltabbakh 2002). Obermair et al. (2004), in a retrospective review of 510 patients submitted to laparoscopic surgery or laparotomy surgery, observed at 29-month follow-up similar patterns of recurrence and similar overall survival in both groups. A recent study of 113 patients with longer follow-up compared the pattern of recurrence and survival after total laparoscopy or laparotomy for early endometrial carcinoma. The two groups presented similar overall survival (Seracchioli et al. 2005). The finding of similar survival outcomes between laparoscopic and laparotomy approach could be the first step in accepting laparoscopy as the standard surgical approach for patients with endometrial carcinoma.

Conclusion

The main strength of our study is its prospective randomized study and longer-term follow-up. This is one of the largest consecutive series of patients with EC treated by total laparoscopic and laparotomy approach. Laparoscopic surgery is a safe and reliable alternative to laparotomy in the management of EC patients, with significantly reduced hospital stay and postoperative complications; however, it does not seem to improve the overall survival and 5-year survival rate, although multicenter randomized trials are required to evaluate the overall oncologic outcomes of this procedure.

References

Abu-Rustum NR, Alektiar K, Iasonos A, Lev G, Sonoda Y, Aghajanian C et al (2006) The incidence of symptomatic lower-extremity lymphedema following treatment of uterine corpus malignancies : a 12-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Gynecol Oncol 103:714–718

Abu-Rustum NR, Gomez JD, Alektiar KM et al (2009) The incidence of isolated paraaortic nodal metastasis in surgically staged endometrial cancer patients with negative pelvic lymph nodes. Gynocol Oncol 115:236–238

ACOG Practice Bulletin (2005) Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 106:413–424

ASTEC Study Group, Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK (2009) Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomized study. Lancet 373:125–136

Benedetti PP, Basile S, Maneschi F, Alberto Lissoni A, Sigorelli M, Scambia G et al (2008) Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:1707–1716

Chan JK, Cheung MK, Huh WK, Osann K, Husain A, Teng NN et al (2006) Therapeutic role of lymph node resection in endometrioid corpus cancer. a study of 12,333 patients. Cancer 107:1823–1830

Chiang AJ, Yu KJ, Chao KC, Teng NN (2011) The incidence of isolated paraaortic nodal metastasis in completely staged endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 121:122–125

Childers JM, Surwit EA (1992) Combined laparoscopic and vaginal surgery for the management of two cases of stage I endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 45:46–51

Clagett GP, Anderson FA Jr, Geerts W, Heit JA, Knudson M, Lieberman JR et al (1998) Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 114:531S–560S

Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn MA, Beller U, Benedet JL et al (2006) Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. FIGO 6th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 95(Suppl 1):S105–S143

DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT, Boronow RC, Blessing JA (1985) Risk factors and recurrent patterns in stage I endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 151:1009–1015

Eltabbakh GH (2002) Analysis of survival after laparoscopy in women with endometrial cnacer. Cancer 95:1894101

Eltabbakh GH, Mount SL (2006) Laparoscopic surgery does not increase the positive peritoneal cytology among women with endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 100:361–364

Eltabbakh GH, Shamonki MI, Moody JM, Garafano LL (2000) Hysterectomy for obese women with endometrial cancer: laparoscopy or laparotomy? Gynecol Oncol 78:329–335

Holland CM, Latimer JA, Crawford RAF (2004) Vaginal cuff recurrence of endometrial cancer treated by laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol 92:1015–1016

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C et al (2006) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 56(2):106–130

Jie J, Zhang Z-Y, Li Z, Liu C, Zhan Y, Qiao B et al (2012) Two mechanical methods for thromboembolism prophylaxis after gynaecological pelvic surgery: a prospective, randomized study. CMJ 125:4259–4263

Kalogiannidis Ioannis, Lambrechts Sandrijne, Amant Frederic, Neven Patrick, Van Gorp Toon, Vergote Ignace (2007) Laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy in clinical stage I endometrial cancer: safety, recurrence, and long-term outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196:248.e1–248.e8

Magrina JF, Mutone NF, Weaver AL, Magtibay PM, Fowler RS, Cornella JL (1999) Laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for endometrial cancer: morbidity and survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181:376–381

Malur S, Possover M, Michels W, Schneider A (2001) Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal versus abdominal surgery in patients with endometrial cancer-a prospective randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol 80:239–244

Malzoni Mario, Tinelli R, Cosentino F, Perone C, Rasile M, Iuzzolino D, Malzoni C (2009) Harry Reich total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy for early-stage endometrial cancer: a prospective randomized study. Gynecol Oncol 112:126–133

May K, Bryant A, Dickinson HO, Kehoe S, Morrison J (2010) Lymphadenectomy for the management of endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD7585

Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Kurman RJ, Creasman WT, Heller P, Homesley HD, Graham JE (1991) Relationship between surgical pathological risk factors and outcome in clinical stage I and II carcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 40:55–65

Mourits MJ, Bijen CB, Arts HJ et al (2010) Safety of laparoscopy versus laparotomy in early stage endometrial cancer: a randomized trial. Lancet Oncol 11:763–771

Muntz HG, Goff BA, Madsen BL, Yon JL (1999) Port-site recurrence after laparoscopic surgery for endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 93:807–809

Nunns D, Williamson K, Swaney L, Davy M (2000) The morbidity of surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in the management of endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 10:2333–2338

Obermair A, Manolitsas TP, Leung Y, Hammond IG, McCartney AJ (2004) Total laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometrial cancer: patterns of recurrence and survival. Gyneco Oncol 92:789–793

Palomba S, Falbo A, Mocciaro R, Russo T, Zullo F (2009) Laparoscopic treatment for endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Gynecol Oncol 112:415–421

Salani R, Gerardi MA, Barlin JN, Veras E, Bristow RE (2009) Surgical approaches and short-term surgical outcomes for patients with morbid obesity and endometrial cancer. J Gynecol Surg 25:41–48

Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Ceccarini M, Cantarelli M, Ceccaroni M, Pignotti E, De Aloysio D, De Iaco P (2005a) Is total laparoscopic surgery for endometrial carcinoma at risk of local recurrence? Long-term Surviv Anticancer Res 25:2423–2428

Seracchioli R, Venturoli S, Ceccarini M, Cantarelli M, Ceccaroni M, Pignotti E, De Aloysio D, De Laco P (2005b) Is total laparoscopic surgery for endometrial carcinoma at risk of local recurrence? A long-term survival. Anticancer Res 25:2423–2428

Todo Y, Yamamoto R, Minobe S, Suzuki Y, Takeshi U, Nakatani M et al (2010a) Risk factors for postoperative lower-extremity lymphedema in endometrial cancer survivors who had treatment including lymphadenectomy. Gynecol Oncol 119:60–64

Todo Y, Kato H, Kaneuchi M, Watari H, Takeda M, Sakuragi N (2010b) Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet 375:1165–1172

Todo Y, Kato H, Kaneuchi I, Watari H, Takeda M, Sakuragi N (2010c) Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet 375:1165–1172

Tozzi R, Malur S, Koehler C, Schneider A (2005) Analysis of morbidity in patients with endometrial cancer: is there a commitment to offer laparoscopy? Gynecol Oncol 97:4–9

Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, Eisenkop SM, Schlaerth JB, Mannel RS (2009) Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J Clin Oncol 27:5331–5336

Yun-Hyun Cho, Dae-Yeon Kim, Jong-Hyeok Kim, Yong-Man Kim, Young-Tak Kim, Joo-Hyun Nam (2007) Laparoscopic management of early uterine cancer: 10-year experience in Asan Medical Center 106:585–590

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Q., Liu, H., Liu, C. et al. Comparison of laparoscopy and laparotomy for management of endometrial carcinoma: a prospective randomized study with 11-year experience. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 139, 1853–1859 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-013-1504-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-013-1504-3