Abstract

The World Health Organization recently published the 4th edition of the Classification of Head and Neck Tumors, including several new entities, emerging entities, and significant updates to the classification and characterization of tumor and tumor-like lesions, specifically as it relates to nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and skull base in this overview. Of note, three new entities (NUT carcinoma, seromucinous hamartoma, biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma,) were added to this section, while emerging entities (SMARCB1-deficient carcinoma and HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features) and several tumor-like entities (respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma, chondromesenchymal hamartoma) were included as provisional diagnoses or discussed in the setting of the differential diagnosis. The sinonasal tract houses a significant diversity of entities, but interestingly, the total number of entities has been significantly reduced by excluding tumor types if they did not occur exclusively or predominantly at this site or if they are discussed in detail elsewhere in the book. Refinements to nomenclature and criteria were provided to sinonasal papilloma, borderline soft tissue tumors, and neuroendocrine neoplasms. Overall, the new WHO classification reflects the state of current understanding for many relatively rare neoplasms, with this article highlighting the most significant changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The 2017 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of tumors of the head and neck, specifically as it relates to the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and skull base (chapter 1, herein after referred to collectively as sinonasal tract), has undergone a complete overhaul [1]. The sinonasal tract encompasses a wide diversity of entities, but significantly, the number of entities has been reduced by omitting tumors or tumor-like lesions when they do not occur exclusively or predominantly at this site or if they are discussed in detail elsewhere in the book. The chapter is separated into major groups, from the most common malignant epithelial tumors (squamous cell carcinoma) [2, 3], followed by the newly included NUT carcinoma [4], then neuroendocrine carcinoma [5], adenocarcinoma [6, 7], and teratocarcinosarcoma [8], before benign epithelial proliferations (papilloma [9–11], respiratory epithelial lesions [12, 13] and salivary gland tumors) are discussed. Malignant, borderline, and benign soft tissue tumors include the newly described biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma [14] and a more complete description of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and chondromesenchymal hamartoma [15]. Brief descriptions of extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma and extraosseous plasmacytoma highlight only the findings within the sinonasal tract. Finally, the neuroectodermal and melanocytic tumors are included, specifically addressing only the significant findings in the sinonasal tract. The classification reflects the current state of understanding for these uncommon entities, and this article will cover entities in the same order as the book, specifically focusing on changes, nomenclature revisions, and new or provisional entities.

Squamous cell carcinoma: keratinizing and non-keratinizing

Squamous cell carcinoma is by far the most common malignancy of the sinonasal tract. The keratinizing (KSCC), non-keratinizing (NKSCC), spindle cell (sarcomatoid), and lymphoepithelial variants are recognized [2, 3]. Other variants, including the verrucous, papillary, basaloid, adenosquamous, and acantholytic, are rare at this anatomic site and have not been included in this new edition in the sinonasal chapter, as they are completely described in sections devoted to other sites where they are more commonly encountered.

KSCC is histologically identical to those tumors arising elsewhere in the upper aerodigestive tract, with nests and cords of tumor cells with variable degrees of keratinization, eliciting a desmoplastic stromal reaction. NKSCC accounts for 15 to 25% of sinonasal SCC. It has a distinctive growth pattern, with invaginating interconnecting ribbons of squamous epithelium with minimal or no evidence of keratinization, and sharply demarcated epithelial-stromal interface, usually with no accompanying desmoplasia. There is maturation of tumor cells with peripheral columnar cells that often show palisading and superficial cells that tend to become flattened. High mitotic activity and areas of necrosis are commonly seen [2].

Sinonasal KSCC and NKSCC show relevant differences in their clinico-pathologic and molecular features, and therefore their separation is relevant. Transcriptionally active high-risk HPV is more frequently detected in NKSCC than in KSCC (35–50 and 0–15%, respectively), although the clinical significance of HPV positivity in sinonasal SCC has not been conclusively assessed as for the oropharynx, and more data need to be collected [16–21]. Moreover, similarly to the oropharynx, absence of TP53 mutation and intact CDKN2A/B are significantly associated with HPV-positive status in sinonasal carcinoma [22].

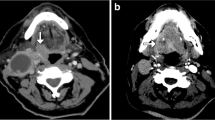

The recently described sinonasal HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features is discussed within the chapter on NKSCC [23]. As the name implies, the histology of this tumor resembles quite closely that of adenoid cystic carcinoma, being formed by solid and cribriform structures of relatively uniform basaloid cells (Fig. 1). Small duct-like structures can be identified in the solid areas, but squamous differentiation is absent. Immunohistochemically, a dual population of myoepithelial cells positive for calponin, p63, actin, and S100, surround a population of c-kit-positive ductal cells. p16 is diffusely positive. The overlying squamous epithelium shows signs of dysplasia/carcinoma in situ (Fig. 1), suggesting that the tumor originates from the surface epithelium, rather than from glands, which is a reason to keep it separate from adenoid cystic carcinoma. Other relevant differences with adenoid cystic carcinoma are the absence of MYB gene rearrangements and the presence of high-risk HPV (Fig. 1), usually the rare type 33. In the few cases reported so far, the clinical behavior seems to be less aggressive than other high-grade sinonasal malignancies [23, 24]. However, more cases need to be studied to confirm these data and before this tumor can be fully recognized as a separate entity.

HPV-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features. The tumor consists of solid and cribriform nests of basaloid cells invading the sinonasal mucosa (a). High-grade squamous dysplasia is present in the overlying surface epithelium (b). RNA in situ hybridization for high-risk HPV is diffusely positive (c) (case courtesy Dr. J. A. Bishop)

Both NKSCC and KSCC may arise from sinonasal papillomas. Recently, molecular evidence in support of a role of precursor lesions for sinonasal papillomas has been provided with the identification of the same activating somatic EGRF mutations in the carcinoma and the inverted papilloma [25], and of KRAS mutations in oncocytic papilloma and associated carcinoma [26].

NUT carcinoma

NUT carcinoma is a recently characterized entity that is listed in the WHO classification of sinonasal tumors for the first time [4]. It is defined as a poorly differentiated carcinoma, often with evidence of squamous differentiation, which presents a rearrangement of the nuclear protein in testis (NUTM1) gene on chromosome 15q14. In most cases, the partner gene of the fusion is BRD4 (bromodomain-containing protein 4) on 19p13.1, and less frequently BRD3 or WHSC1L1. Other anatomic sites of the head and neck may be involved but most cases arise in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses [27]. It affects patients of all ages with a predilection for young adults. Histologically, it is a high-grade poorly differentiated carcinoma with “round blue cell” morphology (Fig. 2). Foci of mature keratinized squamous cells may be occasionally seen abruptly juxtaposed to the undifferentiated component (Fig. 2). Brisk mitotic activity, apoptotic bodies, and areas of necrosis are often recognized. The diagnosis requires the identification of NUTM1 gene rearrangement, by FISH or RT-PCR. However, diffuse (>50%) immunohistochemical nuclear staining for NUT (Fig. 2) is considered sensitive and specific enough to support the diagnosis of NUT carcinoma [28]. In addition, NUT carcinoma is positive for cytokeratins, p63, and CD34 (in approximately half of the cases), while it is negative for S100, HMB45, desmin, myoglobin, smooth muscle actin, muscle actin, chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD45, placental alkaline phosphatase, alpha-fetoprotein, neuron specific enolase, CD57, and CD99. HPV and EBV have been negative in all cases tested. NUT carcinoma is a highly aggressive tumor with a median survival <1 year. However, the recent evidence of clinical response to targeted treatments with bromodomain inhibitors underscores the importance of its distinction from other poorly differentiated carcinomas of the sinonasal tract [29].

Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma

This entity is retained from the previous edition, and it is defined as an undifferentiated carcinoma without glandular or squamous features and not otherwise classifiable [30]. Thus, it mainly remains a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring separation from several other epithelial and non-epithelial high-grade sinonasal malignancies. The recently described subset of undifferentiated carcinomas with rhabdoid histologic features and loss of SMARCB1(INI1) is retained under the umbrella of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (SNUC) as it is still not clear whether it represents a distinct entity. These are highly aggressive carcinomas histologically composed of infiltrating nests of relatively uniform basaloid cells (Fig. 3) but at least some elements have abundant, eccentric, eosinophilic cytoplasm, imparting a rhabdoid appearance [31–33]. The hallmark of these tumors is the complete loss of SMARCB1 expression by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3), which is associated in most cases with homozygous deletion of SMARCB1 [31].

Sinonasal SMARCB1-deficient carcinoma consists of infiltrating nests of undifferentiated basaloid cells (a). Some elements are larger and present a rhabdoid morphology (b). Loss of SMARCB1 (INI1) expression by neoplastic cells is necessary for the diagnosis. The staining is retained by stromal cells (c)

Using next-generation sequencing, IDH2 mutations at R172 were recently identified in 6 of 11 (55%) SNUCs [34]. This suggests the existence of other genomically defined subsets of undifferentiated carcinomas within the spectrum of SNUC.

Neuroendocrine carcinoma: small cell and large cell types

Originally, SNT neuroendocrine neoplasms were not going to be separated out as a specific chapter, but consensus discussion felt the differential consideration and overlap with other SNT entities demanded inclusion. The previous edition referred to these as neuroendocrine tumors and used the terms typical carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, and small cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine type. Typical carcinoid is so vanishingly rare in this site; it was not specifically addressed. But, in keeping with other anatomic sites, neuroendocrine carcinoma is the preferred nomenclature, separated into small cell and large cell types. Sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma (SNEC) is a high-grade malignant epithelial neoplasm showing morphologic (i.e., light microscopic) as well as immunohistochemical features of neuroendocrine differentiation [5]. The specific histologic features of small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas are morphologically identical to the much more common lung counterparts and thus do not need to be presented in detail here. However, many sinonasal malignancies show neuroendocrine features, such as olfactory neuroblastoma (ONB), SNEC, NUT carcinoma, and SNUC, while ectopic pituitary adenoma and paraganglioma are benign tumors within the neuroendocrine category. Thus, accurate separation is necessary due to differences in management and therapies employed. In short, SNEC are rare (~3% of sinonasal tract tumors), usually seen in middle- to older-aged patients, and primarily in men [35–38]. Rare cases show an association with transcriptionally active high-risk HPV [19, 20], but curiously there is not the same strong smoking association seen in other organs [39]. Patients present at an advanced stage with frequently local and distant metastases, especially in small cell carcinoma [38, 40, 41]. Importantly, the neoplastic cells must show light microscopic evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation, even though epithelial features tend to be more easily identified in SNT neoplasms. The tumors show significant destructive infiltration of the bones of the midface. Prominent crush artifacts and tumor necrosis along with a high mitotic index may hinder interpretation. Significantly, there is a lack of neurofibrillary stroma, no glandular or squamous differentiation, and generally a minimal to absent lymphoid infiltrate (Fig. 4) [42, 43]. SCC or adenocarcinoma that lack light microscopic features of neuroendocrine differentiation even when showing focal or patchy neuroendocrine immunoreactivity must still be kept in the original category, not diagnosed as neuroendocrine carcinomas. The dot-like or paranuclear reactivity with keratins (Fig. 4) or other neuroendocrine markers is a feature usually seen in neuroendocrine tumors rather than other neoplasms in the differential diagnosis [42, 44–46]. Ultimately, these are biologically aggressive tumors which require multimodality therapy [35, 40, 47, 48].

Sinonasal small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma consists of nests of uniform round cells infiltrating the mucosa (a). In large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, the nuclei are more irregular and some contain prominent nucleoli (b). Tumor cells are positive for pancytokeratin (paranuclear dot) (c) and for synaptophysin (d)

Adenocarcinoma: intestinal-type and non-intestinal-type

As in the previous edition, sinonasal adenocarcinomas are further distinguished as intestinal type and non-intestinal type [6, 7]. The intestinal-type adenocarcinoma (ITAC) is morphologically and immunophenotypically similar to primary adenocarcinomas of the intestines (Fig. 5). Neoplastic cells are typically positive for markers of intestinal differentiation, including cytokeratin 20, CDX2 (Fig. 5), MUC2, and villin. Their separation from other glandular-type sinonasal neoplasms is important because of the strong relationship with occupational exposures to wood and leather dusts and for the frequent aggressive behavior. They have a papillary, tubular, solid, or mixed growth pattern, and a minority of cases shows abundant mucous production, either extra- or intracellular, including a signet ring morphology. The survival is variable and it is related to the histologic grade.

Since the 3rd edition was published, more cases have been studied at the molecular level. The most frequently detected alterations are TP53 mutation and alteration of CDKN2A [49–51]. KRAS mutations have been reported in 6–40% of the cases, while BRAF mutations are detected in <10% [52–54]. EGFR mutations and amplifications are observed in a minority of cases [52, 53, 55].

Low grade non-intestinal-type adenocarcinoma must be kept separated from other non-salivary-type sinonasal adenocarcinomas since they have an excellent prognosis, with only rare local recurrence. Histologically, the have a tubulo-glandular or papillary architecture and are composed of cuboidal to columnar cells with only focal mild atypia (Fig. 5). In this new edition, it is recognized that rare cases may histologically resemble metastatic renal carcinoma and such examples are designated as sinonasal renal cell-like adenocarcinoma (Fig. 6) [56–58]. They have a distinctive histologic appearance, being composed of a uniform population of cuboidal to columnar cells with glycogen-rich clear cytoplasm without mucin production (Fig. 6). The neoplastic cells are strongly positive with CK7 and CAIX, but negative with PAX-8 and RCC.

The group of high-grade non-ITAC is histologically very heterogeneous, both cytologically and architecturally, but cellular pleomorphism, brisk mitotic activity, necrosis, and infiltrative growth are common features in all cases [59]. Thus, it is likely that high-grade non-ITAC does not represent a distinct entity, but rather a collection of several different adenocarcinoma types, and that in the near future, it will need further characterization, no doubt with the aid of molecular techniques.

Sinonasal papilloma: inverted, oncocytic, and exophytic types

One of the major tenants of the new edition was to eschew all eponyms if possible. Thus, Schneiderian papillomas (named after Konrad Viktor Schneider, 1614–1680) were reclassified as sinonasal papillomas, while still maintaining the three major subtypes: inverted, oncocytic, and exophytic, identical subtypes as used in the previous edition [60]. There were updates on the etiology as it relates to human papillomavirus serovars (low-risk versus high-risk serovars), inclusion of information regarding activating mutations in the EGFR gene, and the unique histologic appearance of the oncocytic type. Even though a benign tumor, various staging systems using the extent of disease as measured by radiographic or endoscopic findings may be employed [61, 62]. Recent studies have suggested malignant association is a synchronous rather than a metachronous finding [63]. In order to be certain dysplasia or carcinoma is not overlooked, thorough histologic review of all submitted material is recommended. Overall, the histologic features, anatomic distribution and prognosis, and predictive factors remained similar to the previous edition. The key histologic features to keep in mind are the presence of a multilayered epithelium, often showing a ciliated columnar epithelial surface layer and showing well-developed transepithelial migration of neutrophils with the development of microabscesses with mucinous debris [64–66].

Respiratory epithelial lesions

Under this new heading, the WHO classification includes two rare benign acquired lesions of the sinonasal tract, respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma (REAH) and seromucinous hamartoma (SH) [12, 13]. Indeed, cases presenting histologic features of both REAH and SH have been reported, suggesting that they may represent a spectrum of the same lesion rather than different entities [67]. It still remains to be determined whether they are of neoplastic or non-neoplastic nature, although the presence of an increased fractional allelic loss in REAH supports the hypothesis of a benign neoplasm [68].

Both lesions occur mainly in adult patients and arise predominantly from the posterior nasal septum. Histologically, REAH is composed of gland-like structures arising in continuity with the surface epithelium, lined by multilayered ciliated respiratory epithelium, often with admixed mucous producing cells. These glands are characteristically surrounded by a thick eosinophilic basement membrane. Squamous metaplasia, as well as osseous or cartilaginous metaplasia can be present. The term chondro-osseous respiratory epithelial hamartoma has been used to report such cases. An inflammatory background is also frequently observed.

SH consists of a proliferation of small glands and tubules lined by a single layer of cuboidal cells, organized in clusters and lobules (Fig. 7). These are intermixed with the pre-existing seromucinous glands of the nasal mucosa, often in relationship with invaginated surface respiratory epithelium gland-like structures that resemble REAH. Myoepithelial cells are usually not recognized around the proliferating glands.

Chondromesenchymal hamartoma

This mesenchymal hamartomatous lesion is included for the first time in the WHO classification [15], although it has been recognized as a distinct entity two decades ago [69]. It occurs predominantly in infants, with involvement of the paranasal sinuses, nasal cavities, and orbit. The behavior is benign, but local invasiveness with intracranial extension through the cribriform plate is described. Sinonasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma is associated with the pleuropulmonary blastoma tumor predisposition disorder, which is due to germline or somatic mutations of the DICER gene [70]. It consists of variably sized nodules of hyaline cartilage, set within a stromal component of spindle cells (Fig. 8). The latter can be loose and myxoid or very cellular, with recognizable mitotic figures. Bony trabeculae surround the cartilage nodules and epithelial as well as mature adipose tissue components may also be present [71].

Malignant soft tissue tumors

Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma

It is quite uncommon in the twenty-first century to get new entities added to the WHO classification, but biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma (BSNS) [14], formerly low-grade sinonasal sarcoma with neural and myogenic features, is just such a new tumor. No doubt this newly recognized tumor was previously diagnosed as one of the tumors within the current differential diagnosis: fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, cellular schwannoma, or synovial sarcoma [72–75]. The distinctive histologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features, most commonly the recurrent PAX3-MAML3 gene fusion allow for this tumor to be separated from these histologic mimics [76, 77].

BSNS affects females more often than males (2:1), with a presentation in the 6th decade [76, 78, 79]. Any site may be affected, although the superior nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus is more commonly affected by a tumor about 4 cm in average greatest dimension. The distinctive histologic features include a bland, spindle cell proliferation arranged in fascicles below an intact, proliferative surface epithelium (Fig. 9). The invaginations of squamous or respiratory-type epithelium may mimic a sinonasal papilloma or a synovial sarcoma (Fig. 9). The nuclei are elongated and slender. Mitoses are inconspicuous and necrosis is not appreciated. Infiltration into adjacent tissues, including bone is common [76, 78, 79]. Uncommonly, a hemangiopericytoma-like vascular pattern is seen, while focal rhabdomyoblastic differentiation may be identified (the latter often associated with an alternate fusion partner) [79]. The neoplastic cells will show a focal, patchy to diffuse (i.e., variable) immunoreactivity with S100 protein, SMA, or MSA (Fig. 9), but are negative with SOX10. Focal desmin, MYOD1 and myogenin (in rhabdomyoblastic areas), and isolated keratin and EMA-positive cells may be seen [76, 79]. The characteristic translocation t(2;4)(q35;q31.1) yields the PAX3-MAML3 fusion transcript [77], while the tumors with rhabdomyoblastic features may harbor PAX3-FOXO1 and PAX3-NCOA1 fusion genes [79–81]. Tumors commonly develop recurrence (50%), but distant metastases and death from disease have not been reported thus far [76].

Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma consists of elongated fascicles of bland appearing spindle cells infiltrating the bone (a). Entrapped gland-like structures derived from the surface epithelium accompany the proliferation (b). Tumor cells are variably positive for S100 protein (c) and smooth muscle actin (d)

Synovial sarcoma

Synovial sarcoma (SS) was previously included in the hypopharynx chapter, where it received only a cursory paragraph. In the current edition [82], there is an expanded coverage of the topic, but it is included in the sinonasal tract primarily as a differential diagnostic consideration for biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma (BSNS). The skull base and neck are occasionally affected, where the monophasic or biphasic subtypes may be seen. One of the helpful findings is a strong TLE1 nuclear immunoreactivity, patchy reactivity with EMA, and cytokeratins (CK7), while usually negative for S100 protein and SMA. The characteristic chromosomal translocation t(X;18)(p11;q11), results in a gene fusion between SYT and SSX genes, distinctly different from BSNS [83, 84].

Borderline soft tissue tumors

Desmoid-type fibromatosis

Desmoid-type fibromatosis, a locally infiltrative, non-metastasizing cytologically bland (myo)fibroblastic neoplasm [85], has recently been recognized to be associated with CTNNB1 (β-catenin encoding gene) mutations in up to 85% of sporadic cases [86–88], while Gardner-type FAP syndrome-associated tumors show germline mutations of the APC gene [89–91]. The changes in CTNNB1 gene yield a very strong nuclear ß-catenin expression by immunohistochemistry [92–94]. The tumors are cellular, showing a fascicular growth with moderate cellularity of spindled cells that have tapered nuclei with a syncytial cytoplasm set within a variably collagenized stroma.

Sinonasal glomangiopericytoma

A sinonasal tumor demonstrating perivascular myoid phenotype [85], glomangiopericytoma, was included in the previous edition, but additional findings were incorporated into the current edition [95–97]. The tumors are unencapsulated, submucosal patternless proliferations, arranged in short fascicles and storiform to short palisades of a syncytial closely packed spindled cell proliferation. A prominent, thick, acellular peritheliomatous hyalinization of the richly vascularized neoplasm is quite characteristic (Fig. 10). The neoplastic cells show a strong reaction with actins (smooth muscle > muscle specific), nuclear β-catenin (Fig. 10), and cyclin-D1, without any significant expression of CD34, CD31, CD117, STAT6, bcl-2, keratins, desmin, or S100 protein [95, 96, 98]. Similar to desmoid-type fibromatosis, glomangiopericytoma shows somatic, single nucleotide mutations in the CTNNB1 gene that encodes β-catenin [96, 97], which results in nuclear accumulation of β-catenin (detected by immunohistochemistry) and shows up-regulation of cyclin D1 [96]. Especially helpful in the differential is a lack of NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion, a feature of solitary fibrous tumor [99].

Glomangiopericytoma is formed by a uniform population of ovoid cells with scanty eosinophilic cytoplasm and characteristically contains vessels surrounded by a thick hyaline membrane (a). The presence of somatic mutations in the CTNNB1 gene results in diffuse and strong nuclear β-catenin immunoreactivity (b)

Solitary fibrous tumor

In the 3rd edition, solitary fibrous tumor was almost a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring a combination of architectural, histochemical, and immunohistochemical findings, that showed morphologic overlap with several other tumors in the SNT. Recent studies have elaborated the fusion gene associated tumor of fibroblastic phenotype that shows a branching vascular pattern to be associated with a fairly unique and specific NAB2-STAT6 fusion [85, 100–102]. This bland spindle cell proliferation usually shows stellate to staghorn-like vessels associated with a variable collagenous background (Fig. 11). Unique from other tumors in the differential diagnosis, there is a strong CD34 and nuclear STAT6 reaction (Fig. 11), but a lack of reactivity with desmin, S100 protein, actins, and nuclear β-catenin [99, 103, 104].

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

In keeping with the newly identified, translocation-associated neoplasms, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma was included in this edition of the classification [85]. The head and neck is rarely affected [105–108] by this slow-growing, infiltrative tumor that frequently shows lymph node metastasis [108]. The tumors often show a multinodular appearance macroscopically, with both an epithelioid and histiocytoid appearance to the endothelial cells arranged in cords and strands of cells that exhibit subtle intracytoplasmic lumina within the ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Profound nuclear pleomorphism is seen in up to 30% of cases. A myxohyaline stroma is seen in the background, while mitoses are sparse [105, 106, 108–110]. Although various endothelial markers are usually positive (CD31, ERG, FLI1), keratin expression is present in about 30% of cases, resulting in misclassification [108, 109]. There is usually a WWTR1-CAMTA1 present in most of the cases, with a subset of cases showing a YAP1-TFE3 fusion [107, 108, 111, 112]. Tumors are generally indolent, although tumors with >3 mitoses/50 HPFs and tumors >3 cm show higher mortality [105, 109, 110].

Hematolymphoid tumors

Any hematolymphoid neoplasm may develop within the sinonasal tract, but for classification purposes, the extranodal natural killer (NK)/T cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKTLNT) has a specific predilection for the sinonasal tract, a cytotoxic phenotype, and a universal association with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [113–118]. Overall, lymphomas represent the third most common malignancy of the SNT tract [119, 120]. ENKTLNT has a strong predilection for East Asians and Latin Americans [114–116], but has increased in other countries [114]. There is involvement of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, although other extranodal sites may be affected. The clinical presentation usually begins non-specifically, simulating chronic rhinosinusitis, but eventually progresses to perforation, ulceration, and even extension into the soft tissues and skin of the face. Arranged in an angiocentric and angiodestructive/invasive pattern, there is usually significant geographic necrosis, often obscuring the underlying viable tumor cells. The neoplastic cells are quite variable, but show irregular contours, folds, and grooves, with increased mitoses. There is usually CD3 and other cytotoxic markers (TIA-1, granzyme B, perforin) immunoreactivity, while CD56 is seen more often in NK cell tumors [121–124] and CD30 is seen in large cell morphology lesions. CD57 is nearly always negative [121, 122]. There is nearly universal EBV detection by in situ hybridization [125–127], with tumors that lack EBER, considered peripheral T cell lymphoma, unspecified [126, 128]. The JAK/STAT pathway is activated in the majority of ENKTLNT, as a result of genetic alterations of JAK3, STAT3, or PTPRK [129–132].

Neuroectodermal/melanocytic tumors

Ewing sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumors

There was no specific change in the diagnostic criteria of this high-grade primitive small round cell sarcoma that shows variable neuroectodermal differentiation [133–136]. However, Ewing sarcoma, classically defined by the presence of a translocation between EWSR1 gene on chromosome 22 and the FLI1 gene on chromosome 11, is well-known to increasingly show greater diversity in the translocation partners, and even perhaps showing similar morphology, but a completely different molecular profile and often associated with a unique histologic appearance (such as adamantinoma-like) [137, 138]. Importantly, these tumors usually show a strong and diffuse membranous immunoreactivity with CD99, while FLI1 and ERG show nuclear reactions when the fusion partner is FLI1 or ERG, respectively [139–141]. Focal to diffuse and weak to strong cytokeratin reaction may be seen, although more frequently in the adamantinoma-like Ewing family tumors [136, 138, 142]. At present, EWSR1-negative cases may show the CIC-DUX4 fusion, the result of t(4;19) or t(10;19) translocation [143], but these tumors show variable CD99 expression and nuclear heterogeneity and are usually soft tissue tumors of the extremities [144].

Olfactory neuroblastoma

The neuroectodermal tumors are sometimes very difficult to characterize. Olfactory neuroblastoma is a malignant neuroectodermal neoplasm with neuroblastic differentiation, most often localized to the superior nasal cavity [133]. Very uncommon, the tumor seems to show a peak in the 5th–6th decades [145–147], with males affected slightly more often than females (1.2:1). The site of tumor development is stressed for this neoplasm, which must involve the cribriform plate of the ethmoid sinus, part of the superior turbinate (concha), or the superior half of the nasal septum, with other sites of involvement a diagnosis of exclusion (unless recurrent) [148]. Even though there is marked destruction of the olfactory apparatus, anosmia is only reported in <5% of patients. Imaging must be incorporated into the interpretation, with the classic “dumbbell-shaped” mass extending across the cribriform plate very helpful. Staging is done by the Kadish [149] or the Morita modified Kadish classification system [150]. Low-grade tumors, with their characteristic submucosal, sharply demarcated lobular architecture of small cells with round to oval nuclei with delicate “salt-and-pepper” chromatin are easily diagnosed, even when fibrillary matrix (neuropil) or rosettes are absent. However, it is higher grade tumors that demonstrate nuclear pleomorphism, nucleoli, tumor necrosis, increased mitoses, and decreased to absent neuropil, which are much more difficult to recognize and diagnose. Melanin pigment, ganglion cells, rhabdomyoblasts, and divergent differentiation as islands of true epithelium (squamous pearls or gland formation), further complicate diagnosis [151–155]. For the vast majority of cases, ONBs show scant or focal to completely absent expression of keratins (including EMA and CAM5.2) [156], but usually show strong and diffuse immunoreactivity with synaptophysin, chromogranin-A, CD56, neurofibrillary protein, and calretinin (nuclear and cytoplasmic) [45]. The sustentacular cells at the periphery of the cell nests are highlighted by both S100 protein and glial filament acidic protein (GFAP). It is this latter finding that may help with separation from other small round blue cell tumors of the SNT that may show histological and immunophenotypic overlap [157]. The prognostic value of the Hyams grading system based on tumor architecture, pleomorphism, neural matrix, mitotic activity, necrosis, and gland/rosette presence was reinforced by inclusion in the chapter [158–161]. Recent work suggests that the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway seems to play a role in pathogenesis [162], while EWSR1 rearrangements are not seen.

Mucosal melanoma

Sinonasal tract mucosal melanoma was updated to include new information specifically regarding molecular mutational status, as the NRAS and KIT mutations/amplifications are seen with a much higher frequency than BRAF mutations, a sharp contrast to cutaneous and uveal primary tumors, resulting in a difference in management and patient outcome [133].

Entities excluded

A number of entities were removed from the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and skull base section, including the following: verrucous carcinoma, papillary squamous cell carcinoma, basaloid squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma, all of the malignant salivary gland-type carcinomas, typical carcinoid, myoepithelioma, oncocytoma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, myxoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, chordoma, all benign bone and cartilage tumors, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, extramedullary myeloid sarcoma, histiocytic sarcoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy, all germ cell tumors, and secondary tumors. It was determined that the histologic features of these entities is sufficiently well described in other parts of the book and duplication served no useful purpose. Further, many of these entities are covered in great detail in their respective books on the topic (bone, cartilage, soft tissue, central nervous system, and lymph node and hematolymphoid tumors).

References

El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors (2017) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. Lyon, France: IARC

Bishop JA, Bell D, Westra WH (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: carcinomas: keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 14–15

Bishop JA, Brandwein-Gensler M, Nicolai P, Steens S, Syrjänen S, Westra WH (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: carcinomas: non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 15–17

French CA, Bishop JA, Lewis JS Jr, Müller S, Westra WH (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: carcinomas: NUT carcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 20–21

Thompson LDR, Bell D, Bishop JA (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: neuroendocrine carcinomas. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 21–23

Stelow EB, Franchi A, Wenig BM (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: carcinomas: intestinal-type adenocarcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 23–24

Stelow EB, Brandwein-Gensler M, Franchi A, Nicolai P, Wenig BM (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: carcinomas: non-intestinal-type adenocarcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 24–26

Franchi A, Wenig BM (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: teratocarcinosarcoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 26–27

Hunt JL, Bell D, Sarioglu S (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: sinonasal papillomas: Sinonasal papilloma, inverted type. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 28–31

Hunt JL, Chiosea S, Sarioglu S (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: sinonasal papillomas: Sinonasal papilloma, oncocytic type. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 29–30

Hunt JL, Lewis JS Jr, Richardson M, Sarioglu S, Syrjanen K (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: sinonasal papillomas: Sinonasal papilloma, exophytic type. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 30–31

Wenig BM, Franchi A, Ro JY (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: respiratory epithelial lesions: respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 31–32

Ro JY, Franchi A (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: respiratory epithelial lesions: seromucinous hamartoma. In: El-Naggar AK, JKC C, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, p 32

Lewis JE, Oliveira AM (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: malignant soft tissue Tumours: biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 40–41

Toner M, Hunt JL (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: other tumours: chondromesenchymal hamartoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 51–52

El-Mofty SK, Lu DW (2005) Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in nonkeratinizing (cylindrical cell) carcinoma of the sinonasal tract: a distinct clinicopathologic and molecular disease entity. Am J Surg Pathol 29:1367–1372

Alos L, Moyano S, Nadal A et al (2009) Human papillomaviruses are identified in a subgroup of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas with favorable outcome. Cancer 115:2701–2709

Larque AB, Hakim S, Ordi J et al (2014) High-risk human papillomavirus is transcriptionally active in a subset of sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol 27:343–351

Bishop JA, Guo TW, Smith DF et al (2013) Human papillomavirus-related carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 37:185–192

Laco J, Sieglova K, Vosmikova H et al (2015) The presence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 mRNA transcripts in a subset of sinonasal carcinomas is evidence of involvement of HPV in its etiopathogenesis. Virchows Arch 467:405–415

Lewis JS Jr (2016) Sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma: a review with emphasis on emerging histologic subtypes and the role of human papillomavirus. Head Neck Pathol. 10:60–67

Chung CH, Guthrie VB, Masica DL et al (2015) Genomic alterations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma determined by cancer gene-targeted sequencing. Ann Oncol 26:1216–1223

Bishop JA, Ogawa T, Stelow EB et al (2013) Human papillomavirus-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features: a peculiar variant of head and neck cancer restricted to the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 37:836–844

Andreasen S, Bishop JA, Hansen TV, et al (2016) Human papillomavirus-related carcinoma with adenoid cystic-like features of the sinonasal tract: clinical and morphological characterization of six new cases. Histopathol doi: 10.1111/his.13162

Udager AM, Rolland DC, McHugh JB et al (2015) High-frequency targetable EGFR mutations in sinonasal squamous cell carcinomas arising from inverted sinonasal papilloma. Cancer Res 75:2600–2606

Udager AM, McHugh JB, Betz BL et al (2016) Activating KRAS mutations are characteristic of oncocytic sinonasal papilloma and associated sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol 239:394–398

Bishop JA, Westra WH (2012) NUT midline carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 36:1216–1221

Haack H, Johnson LA, Fry CJ et al (2009) Diagnosis of NUT midline carcinoma using a NUT-specific monoclonal antibody. Am J Surg Pathol 33:984–991

Stathis A, Zucca E, Bekradda M et al (2016) Clinical response of carcinomas harboring the BRD4-NUT oncoprotein to the targeted bromodomain inhibitor OTX015/MK-8628. Cancer Discov. 6:492–500

Lewis JS Jr, Bishop JA, Gillison M, Westra WH, Yarborough WG (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: carcinomas: sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 18–20

Bishop JA, Antonescu CR, Westra WH (2014) SMARCB1 (INI-1)-deficient carcinomas of the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 38:1282–1289

Agaimy A, Koch M, Lell M et al (2014) SMARCB1(INI1)-deficient sinonasal basaloid carcinoma: a novel member of the expanding family of SMARCB1-deficient neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 38:1274–1281

Bell D, Hanna EY, Agaimy A, Weissferdt A (2015) Reappraisal of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: SMARCB1 (INI1)-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a single-institution experience. Virchows Arch 467:649–656

Jo VY, Chau NG, Hornick JL, Krane JF, Sholl LM (2017) Recurrent IDH2 R172X mutations in sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Mod Pathol doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.239

Patel TD, Vazquez A, Dubal PM, Baredes S, Liu JK, Eloy JA (2015) Sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma: a population-based analysis of incidence and survival. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 5:448–453

Chai L, Ying HF, Wu TT et al (2014) Clinical features and hypoxic marker expression of primary sinonasal and laryngeal small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: a small case series. World J Surg Oncol 12:199

Huang S, Zhao Y, He L, Dan LV, Yang F (2013) Clinical analysis and review of 8 cases with sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 27:751–753

Qian GH, Shang JB, Wang KJ, Tan Z (2011) Diagnosis and treatment of 11 cases with sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 46:1033–1035

Su SY, Bell D, Hanna EY (2014) Esthesioneuroblastoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma: differentiation in diagnosis and treatment. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 18:S149–S156

Mitchell EH, Diaz A, Yilmaz T et al (2012) Multimodality treatment for sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Head Neck. 34:1372–1376

Likhacheva A, Rosenthal DI, Hanna E, Kupferman M, Demonte F, El-Naggar AK (2011) Sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma: impact of differentiation status on response and outcome. Head Neck Oncol 3:32

Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B (2007) Non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the sinonasal tract and nasopharynx. Report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 1:21–26

Sugita Y, Kusano K, Tokunaga O et al (2006) Olfactory neuroepithelioma: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Neuropathology 26:400–408

Cordes B, Williams MD, Tirado Y et al (2009) Molecular and phenotypic analysis of poorly differentiated sinonasal neoplasms: an integrated approach for early diagnosis and classification. Hum Pathol 40:283–292

Wooff JC, Weinreb I, Perez-Ordonez B, Magee JF, Bullock MJ (2011) Calretinin staining facilitates differentiation of olfactory neuroblastoma from other small round blue cell tumors in the sinonasal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 35:1786–1793

Chapman-Fredricks J, Jorda M, Gomez-Fernandez C (2009) A limited immunohistochemical panel helps differentiate small cell epithelial malignancies of the sinonasal cavity and nasopharynx. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 17:207–210

van der Laan TP, Bij HP, van Hemel BM et al (2013) The importance of multimodality therapy in the treatment of sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 270:2565–2568

Menon S, Pai P, Sengar M, Aggarwal JP, Kane SV (2010) Sinonasal malignancies with neuroendocrine differentiation: case series and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 53:28–34

Holmila R, Bornholdt J, Heikkila P et al (2010) Mutations in TP53 tumor suppressor gene in wood dust-related sinonasal cancer. Int J Cancer 127:578–588

Perrone F, Oggionni M, Birindelli S et al (2003) TP53, p14ARF, p16INK4a and H-ras gene molecular analysis in intestinal-type adenocarcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Int J Cancer 105:196–203

Perez-Escuredo J, Martinez JG, Vivanco B et al (2012) Wood dust-related mutational profile of TP53 in intestinal-type sinonasal adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 43:1894–1901

Franchi A, Innocenti DR, Palomba A et al (2014) Low prevalence of K-RAS, EGF-R and BRAF mutations in sinonasal adenocarcinomas. Implications for anti-EGFR treatments. Pathol Oncol Res 20:571–579

Garcia-Inclan C, Lopez F, Perez-Escuredo J et al (2012) EGFR status and KRAS/BRAF mutations in intestinal-type sinonasal adenocarcinomas. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 35:443–450

Lopez F, Garcia Inclan C, Perez-Escuredo J et al (2012) KRAS and BRAF mutations in sinonasal cancer. Oral Oncol 48:692–697

Franchi A, Fondi C, Paglierani M, Pepi M, Gallo O, Santucci M (2009) Epidermal growth factor receptor expression and gene copy number in sinonasal intestinal type adenocarcinoma. Oral Oncol 45:835–838

Zur KB, Brandwein M, Wang B, Som P, Gordon R, Urken ML (2002) Primary description of a new entity, renal cell-like carcinoma of the nasal cavity: van Meegeren in the house of Vermeer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 128:441–447

Storck K, Hadi UM, Simpson R, Ramer M, Brandwein-Gensler M (2008) Sinonasal renal cell-like adenocarcinoma: a report on four patients. Head Neck Pathol. 2:75–80

Shen T, Shi Q, Velosa C et al (2015) Sinonasal renal cell-like adenocarcinomas: robust carbonic anhydrase expression. Hum Pathol 46:1598–1606

Stelow EB, Jo VY, Mills SE, Carlson DL (2011) A histologic and immunohistochemical study describing the diversity of tumors classified as sinonasal high-grade nonintestinal adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 35:971–980

Hunt JL, Bell D, Chiosea S et al (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: sinonasal papillomas. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 28–31

Anari S, Carrie S (2010) Sinonasal inverted papilloma: narrative review. J Laryngol Otol 124:705–715

Krouse JH (2001) Endoscopic treatment of inverted papilloma: safety and efficacy. Am J Otolaryngol 22:87–99

Nudell J, Chiosea S, Thompson LD (2014) Carcinoma ex-Schneiderian papilloma (malignant transformation): a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 20 cases combined with a comprehensive review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 8:269–286

Barnes L (2002) Schneiderian papillomas and nonsalivary glandular neoplasms of the head and neck. Mod Pathol 15:279–297

Rodic N, Maleki Z (2012) Cytomorphologic findings of Schneiderian papilloma: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol 40:1100–1103

Sarioglu S (2007) Update on inverted epithelial lesions of the sinonasal and nasopharyngeal regions. Head Neck Pathol. 1:44–49

Weinreb I, Gnepp DR, Laver NM et al (2009) Seromucinous hamartomas: a clinicopathological study of a sinonasal glandular lesion lacking myoepithelial cells. Histopathology 54:205–213

Ozolek JA, Hunt JL (2006) Tumor suppressor gene alterations in respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma (REAH): comparison to sinonasal adenocarcinoma and inflamed sinonasal mucosa. Am J Surg Pathol 30:1576–1580

McDermott MB, Ponder TB, Dehner LP (1998) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: an upper respiratory tract analogue of the chest wall mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Surg Pathol 22:425–433

Stewart DR, Messinger Y, Williams GM et al (2014) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartomas arise secondary to germline and somatic mutations of DICER1 in the pleuropulmonary blastoma tumor predisposition disorder. Hum Genet 133:1443–1450

Ozolek JA, Carrau R, Barnes EL, Hunt JL (2005) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in older children and adults: series and immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 129:1444–1450

Heffner DK, Gnepp DR (1992) Sinonasal fibrosarcomas, malignant schwannomas, and “triton” tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 67 cases. Cancer 70:1089–1101

Igwe OJ (2006) Agents that act by different mechanisms modulate the activity of protein kinase CbetaII isozyme in the rat spinal cord during peripheral inflammation. Neuroscience 138:313–328

Hellquist HB, Lundgren J (1991) Neurogenic sarcoma of the sinonasal tract. J Laryngol Otol 105:186–190

Patel TD, Carniol ET, Vazquez A, Baredes S, Liu JK, Eloy JA (2016) Sinonasal fibrosarcoma: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 6:201–205

Lewis JT, Oliveira AM, Nascimento AG et al (2012) Low-grade sinonasal sarcoma with neural and myogenic features: a clinicopathologic analysis of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 36:517–525

Wang X, Bledsoe KL, Graham RP et al (2014) Recurrent PAX3-MAML3 fusion in biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. Nat Genet 46:666–668

Powers KA, Han LM, Chiu AG, Aly FZ (2015) Low-grade sinonasal sarcoma with neural and myogenic features—diagnostic challenge and pathogenic insight. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 119:e265–e269

Huang SC, Ghossein RA, Bishop JA et al (2016) Novel PAX3-NCOA1 fusions in biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma with focal rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 40:51–59

Sumegi J, Streblow R, Frayer RW et al (2010) Recurrent t(2;2) and t(2;8) translocations in rhabdomyosarcoma without the canonical PAX-FOXO1 fuse PAX3 to members of the nuclear receptor transcriptional coactivator family. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 49:224–236

Wong WJ, Lauria A, Hornick JL, Xiao S, Fletcher JA, Marino-Enriquez A (2016) Alternate PAX3-FOXO1 oncogenic fusion in biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 55:25–29

Bullerdiek J, Bell D (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: synovial sarcoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 41–42

Bettio D, Rizzi N, Colombo P, Bianchi P, Gaetani P (2004) Unusual cytogenetic findings in a synovial sarcoma arising in the paranasal sinuses. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 155:79–81

Gil Z, Orr-Urtreger A, Voskoboinik N, Trejo-Leider L, Shomrat R, Fliss DM (2008) Cytogenetic analysis of 101 skull base tumors. Head Neck. 30:567–581

Wenig BM, Flucke U, Thompson LDR (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: boderline/low-grade malignant soft tissue tumours. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 43–46

Huss S, Nehles J, Binot E et al (2013) Beta-catenin (CTNNB1) mutations and clinicopathological features of mesenteric desmoid-type fibromatosis. Histopathology 62:294–304

Le Guellec S, Soubeyran I, Rochaix P et al (2012) CTNNB1 mutation analysis is a useful tool for the diagnosis of desmoid tumors: a study of 260 desmoid tumors and 191 potential morphologic mimics. Mod Pathol 25:1551–1558

Flucke U, Tops BB, van Diest PJ, Slootweg PJ (2014) Desmoid-type fibromatosis of the head and neck region in the paediatric population: a clinicopathological and genetic study of seven cases. Histopathology 64:769–776

Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Zhou H, Fletcher CD (2007) Gardner fibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 45 patients with 57 fibromas. Am J Surg Pathol 31:410–416

Colombo C, Foo WC, Whiting D et al (2012) FAP-related desmoid tumors: a series of 44 patients evaluated in a cancer referral center. Histol Histopathol 27:641–649

Schiessling S, Kihm M, Ganschow P, Kadmon G, Buchler MW, Kadmon M (2013) Desmoid tumour biology in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis coli. Br J Surg 100:694–703

Thway K, Gibson S, Ramsay A, Sebire NJ (2009) Beta-catenin expression in pediatric fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions: a study of 100 cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol 12:292–296

Bhattacharya B, Dilworth HP, Iacobuzio-Donahue C et al (2005) Nuclear beta-catenin expression distinguishes deep fibromatosis from other benign and malignant fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 29:653–659

Carlson JW, Fletcher CD (2007) Immunohistochemistry for beta-catenin in the differential diagnosis of spindle cell lesions: analysis of a series and review of the literature. Histopathology 51:509–514

Thompson LD, Miettinen M, Wenig BM (2003) Sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 104 cases showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 27:737–749

Lasota J, Felisiak-Golabek A, Aly FZ, Wang ZF, Thompson LD, Miettinen M (2015) Nuclear expression and gain-of-function beta-catenin mutation in glomangiopericytoma (sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma): insight into pathogenesis and a diagnostic marker. Mod Pathol 28:715–720

Haller F, Bieg M, Moskalev EA et al (2015) Recurrent mutations within the amino-terminal region of beta-catenin are probable key molecular driver events in sinonasal hemangiopericytoma. Am J Pathol 185:563–571

Agaimy A, Barthelmess S, Geddert H et al (2014) Phenotypical and molecular distinctness of sinonasal haemangiopericytoma compared to solitary fibrous tumour of the sinonasal tract. Histopathology 65:667–673

Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD, Mertens F, Hornick JL (2014) Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol 27:390–395

Mohajeri A, Tayebwa J, Collin A et al (2013) Comprehensive genetic analysis identifies a pathognomonic NAB2/STAT6 fusion gene, nonrandom secondary genomic imbalances, and a characteristic gene expression profile in solitary fibrous tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 52:873–886

Akaike K, Kurisaki-Arakawa A, Hara K et al (2015) Distinct clinicopathological features of NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene variants in solitary fibrous tumor with emphasis on the acquisition of highly malignant potential. Hum Pathol 46:347–356

Demicco EG, Wani K, Fox PS et al (2015) Histologic variability in solitary fibrous tumors reflects angiogenic and growth factor signaling pathway alterations. Hum Pathol 46:1015–1026

Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Ohno M et al (2014) STAT6 immunohistochemistry is helpful in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 38:552–559

Demicco EG, Harms PW, Patel RM et al (2015) Extensive survey of STAT6 expression in a large series of mesenchymal tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 143:672–682

Weiss SW, Enzinger FM (1982) Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a vascular tumor often mistaken for a carcinoma. Cancer 50:970–981

Bruder E, Alaggio R, Kozakewich HP, Jundt G, Dehner LP, Coffin CM (2012) Vascular and perivascular lesions of skin and soft tissues in children and adolescents. Pediatr Dev Pathol 15:26–61

Errani C, Zhang L, Sung YS et al (2011) A novel WWTR1-CAMTA1 gene fusion is a consistent abnormality in epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of different anatomic sites. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 50:644–653

Flucke U, Vogels RJ, de Saint Aubain Somerhausen N et al (2014) Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: clinicopathologic, immunhistochemical, and molecular genetic analysis of 39 cases. Diagn Pathol 9:131

Mentzel T, Beham A, Calonje E, Katenkamp D, Fletcher CD (1997) Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 21:363–374

Deyrup AT, Tighiouart M, Montag AG, Weiss SW (2008) Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma of soft tissue: a proposal for risk stratification based on 49 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 32:924–927

Tanas MR, Sboner A, Oliveira AM et al (2011) Identification of a disease-defining gene fusion in epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Sci Transl Med 3:98ra82

Antonescu CR, Le Loarer F, Mosquera JM et al (2013) Novel YAP1-TFE3 fusion defines a distinct subset of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 52:775–784

Chuang SS, Ferry JA, Gaulard P, Jaffe ES, Ko Y-H (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: haematolymphoid tumours. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 52–55

Dubal PM, Dutta R, Vazquez A, Patel TD, Baredes S, Eloy JA (2015) A comparative population-based analysis of sinonasal diffuse large B-cell and extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomas. Laryngoscope 125:1077–1083

Aoki R, Karube K, Sugita Y et al (2008) Distribution of malignant lymphoma in Japan: analysis of 2260 cases, 2001-2006. Pathol Int 58:174–182

Laurini JA, Perry AM, Boilesen E et al (2012) Classification of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in cCentral and South America: a review of 1028 cases. Blood 120:4795–4801

Crane GM, Duffield AS (2016) Hematolymphoid lesions of the sinonasal tract. Semin Diagn Pathol 33:71–80

Kreisel FH (2016) Hematolymphoid lesions of the sinonasal tract. Head Neck Pathol. 10:109–117

Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Funk GF, Robinson RA, Menck HR (1998) The National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 124:951–962

Cooper JS, Porter K, Mallin K et al (2009) National Cancer Database report on cancer of the head and neck: 10-year update. Head Neck 31:748–758

Pongpruttipan T, Sukpanichnant S, Assanasen T et al (2012) Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, includes cases of natural killer cell and alphabeta, gammadelta, and alphabeta/gammadelta T-cell origin: a comprehensive clinicopathologic and phenotypic study. Am J Surg Pathol 36:481–499

Jhuang JY, Chang ST, Weng SF et al (2015) Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type in Taiwan: a relatively higher frequency of T-cell lineage and poor survival for extranasal tumors. Hum Pathol 46:313–321

Au WY, Weisenburger DD, Intragumtornchai T et al (2009) Clinical differences between nasal and extranasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: a study of 136 cases from the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. Blood 113:3931–3937

Li S, Feng X, Li T et al (2013) Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: a report of 73 cases at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Am J Surg Pathol 37:14–23

Chuang SS, Ko YH (2014) Cutaneous nonmycotic T- and natural killer/T-cell lymphomas: diagnostic challenges and dilemmas. J Am Acad Dermatol 70:724–735

Swerdlow SH, Jaffe ES, Brousset P et al (2014) Cytotoxic T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas: current questions and controversies. Am J Surg Pathol 38:e60–e71

Chuang SS (2014) In situ hybridisation for Epstein-Barr virus as a differential diagnostic tool for T- and natural killer/T-cell lymphomas in non-immunocompromised patients. Pathology 46:581–591

Jaffe ES, Nicolae A, Pittaluga S (2013) Peripheral T-cell and NK-cell lymphomas in the WHO classification: pearls and pitfalls. Mod Pathol 26(Suppl 1):S71–S87

Coppo P, Gouilleux-Gruart V, Huang Y et al (2009) STAT3 transcription factor is constitutively activated and is oncogenic in nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 23:1667–1678

Koo GC, Tan SY, Tang T et al (2012) Janus kinase 3-activating mutations identified in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Discov 2:591–597

Lee S, Park HY, Kang SY et al (2015) Genetic alterations of JAK/STAT cascade and histone modification in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma nasal type. Oncotarget 6:17764–17776

Chen YW, Guo T, Shen L et al (2015) Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase kappa directly targets STAT3 activation for tumor suppression in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Blood 125:1589–1600

Wenig BM, Flucke U, Thompson LDR et al (2017) Tumours of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base: neuroectodermal/melanocytic tumours. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds) WHO classification of head and neck tumours. IARC, Lyon, pp 56–61

Windfuhr JP (2004) Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the head and neck: incidence, diagnosis, and management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 113:533–543

Howarth KL, Khodaei I, Karkanevatos A, Clarke RW (2004) A sinonasal primary Ewing’s sarcoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68:221–224

Hafezi S, Seethala RR, Stelow EB et al (2011) Ewing’s family of tumors of the sinonasal tract and maxillary bone. Head Neck Pathol. 5:8–16

Folpe AL, Goldblum JR, Rubin BP et al (2005) Morphologic and immunophenotypic diversity in Ewing family tumors: a study of 66 genetically confirmed cases. Am J Surg Pathol 29:1025–1033

Bishop JA, Alaggio R, Zhang L, Seethala RR, Antonescu CR (2015) Adamantinoma-like Ewing family tumors of the head and neck: a pitfall in the differential diagnosis of basaloid and myoepithelial carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 39:1267–1274

Machado I, Mayordomo-Aranda E, Scotlandi K, Picci P, Llombart-Bosch A (2014) Immunoreactivity using anti-ERG monoclonal antibodies in sarcomas is influenced by clone selection. Pathol Res Pract 210:508–513

Tomlins SA, Palanisamy N, Brenner JC et al (2013) Usefulness of a monoclonal ERG/FLI1 antibody for immunohistochemical discrimination of Ewing family tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 139:771–779

Wang WL, Patel NR, Caragea M et al (2012) Expression of ERG, an Ets family transcription factor, identifies ERG-rearranged Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol 25:1378–1383

Gu M, Antonescu CR, Guiter G, Huvos AG, Ladanyi M, Zakowski MF (2000) Cytokeratin immunoreactivity in Ewing’s sarcoma: prevalence in 50 cases confirmed by molecular diagnostic studies. Am J Surg Pathol 24:410–416

Italiano A, Sung YS, Zhang L et al (2012) High prevalence of CIC fusion with double-homeobox (DUX4) transcription factors in EWSR1-negative undifferentiated small blue round cell sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 51:207–218

Specht K, Sung YS, Zhang L, Richter GH, Fletcher CD, Antonescu CR (2014) Distinct transcriptional signature and immunoprofile of CIC-DUX4 fusion-positive round cell tumors compared to EWSR1-rearranged Ewing sarcomas: further evidence toward distinct pathologic entities. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 53:622–633

Jethanamest D, Morris LG, Sikora AG, Kutler DI (2007) Esthesioneuroblastoma: a population-based analysis of survival and prognostic factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133:276–280

Platek ME, Merzianu M, Mashtare TL et al (2011) Improved survival following surgery and radiation therapy for olfactory neuroblastoma: analysis of the SEER database. Radiat Oncol 6:41

Broich G, Pagliari A, Ottaviani F (1997) Esthesioneuroblastoma: a general review of the cases published since the discovery of the tumour in 1924. Anticancer Res 17:2683–2706

Thompson LD (2009) Olfactory neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 3:252–259

Kadish S, Goodman M, Wang CC (1976) Olfactory neuroblastoma. A clinical analysis of 17 cases. Cancer 37:1571–1576

Morita A, Ebersold MJ, Olsen KD, Foote RL, Lewis JE, Quast LM (1993) Esthesioneuroblastoma: prognosis and management. Neurosurgery 32:706–714 discussion 714-705

Llombart-Bosch A, Carda C, Peydro-Olaya A, Noguera R, Boix J, Pellin A (1989) Pigmented esthesioneuroblastoma showing dual differentiation following transplantation in nude mice. An immunohistochemical, electron microscopical, and cytogenetic analysis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 414:199–208

Bates T, Plessis DD, Polvikoski T et al (2012) Ganglioneuroblastic transformation in olfactory neuroblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 6:150–155

Miyagami M, Katayama Y, Kinukawa N, Sawada T (2002) An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of olfactory neuroepithelioma with rhabdomyoblasts. Med Electron Microsc 35:160–166

Faragalla H, Weinreb I (2009) Olfactory neuroblastoma: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol 16:322–331

Bishop JA, Thompson LD, Cardesa A et al (2015) Rhabdomyoblastic differentiation in head and neck malignancies other than rhabdomyosarcoma. Head Neck Pathol 9:507–518

Holbrook EH, Wu E, Curry WT, Lin DT, Schwob JE (2011) Immunohistochemical characterization of human olfactory tissue. Laryngoscope 121:1687–1701

Thompson LD (2017) Small round blue cell tumors of the sinonasal tract: a differential diagnosis approach. Mod Pathol 30:S1–s26

Saade RE, Hanna EY, Bell D (2015) Prognosis and biology in esthesioneuroblastoma: the emerging role of Hyams grading system. Curr Oncol Rep 17:423

Tajudeen BA, Arshi A, Suh JD, St John M, Wang MB (2014) Importance of tumor grade in esthesioneuroblastoma survival: a population-based analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 140:1124–1129

Gallagher KK, Spector ME, Pepper JP, McKean EL, Marentette LJ, McHugh JB (2014) Esthesioneuroblastoma: updating histologic grading as it relates to prognosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 123:353–358

Kaur G, Kane AJ, Sughrue ME et al (2013) The prognostic implications of Hyam’s subtype for patients with Kadish stage C esthesioneuroblastoma. J Clin Neurosci 20:281–286

Mao L, Xia YP, Zhou YN et al (2009) Activation of sonic hedgehog signaling pathway in olfactory neuroblastoma. Oncology 77:231–243

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have contributed to this work and they declare that there are no financial conflicts associated with this study.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Copyright transfer agreement

We transfer the right to publish this manuscript in the journal Virchows Archives if accepted for publication. This article is an original work, is not under consideration, and has not been published previously in any form.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, L.D.R., Franchi, A. New tumor entities in the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors: Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Virchows Arch 472, 315–330 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2116-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2116-0