Abstract

Until recently, two major types of colorectal epithelial polyps were distinguished: the adenoma and the hyperplastic polyp. While adenomas—because of their cytological atypia—were recognized as the precursor lesions for colorectal carcinoma, hyperplastic polyps were perceived as harmless lesions without any potential for malignant progression mainly because hyperplastic polyps are missing cytological atypia. Meanwhile, it is recognized that the lesions, formerly classified as hyperplastic, represent a heterogeneous group of polyps with characteristic serrated morphology some of which exhibit a significant risk of neoplastic progression. These serrated lesions show characteristic epigenetic alterations not commonly seen in colorectal adenomas and progress to colorectal carcinoma via the so-called serrated pathway (CpG-island-methylation-phenotype pathway). This group of polyps is comprised not only of hyperplastic polyps, but also of sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas and mixed polyps, showing serrated and “classical” adenomatous features. Diagnostic criteria and nomenclature for these lesions are not uniform and, therefore, somewhat confusing. In a consensus conference of the Working Group of Gastroenterological Pathology of the German Society of Pathology, standardization of nomenclature and diagnostic criteria as well as recommendations for clinical management of these serrated polyps were formulated and are presented herein.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Until recently, epithelial polyps of the colon and rectum have been classified as non-neoplastic lesions, e.g., hyperplastic or metaplastic polyps, and neoplastic adenomas (tubular, tubulovillous, villous) [1]. The distinctive feature was the presence of cytologic dysplasia or intraepithelial neoplasia (IEN), which was considered to be a conditio sine qua non for the diagnosis of an adenoma.

Over the last few years, however, it has been demonstrated that hyperplastic polyps/serrated lesions without the presence of IEN are, in fact, clonal epithelial proliferations with underlying genetic alterations mainly in KRAS [2, 3] and BRAF [4–6]. In addition, it has been shown that the normal shedding of epithelium, which is induced by a special form of apoptosis (anoikis), is blocked in hyperplastic polyps (and serrated adenomas). Presumably, this inhibition is mediated by activated/mutated RAS or RAF [7, 8]. The characteristic serrated morphology of the crypts can be explained by a high number of retained cells with defective anoikis [9]. As early as 1999, Iino and Jass found hyperplastic/serrated polyps preceding microsatellite instability (MSI) colorectal carcinomas indicating that serrated polyps are involved in the carcinogenesis of a subgroup of colorectal carcinomas [10, 11]. On the other hand, Jass et al. demonstrated that “classical” adenomas are most likely not the precursor lesions of sporadic colorectal carcinomas with high (type 1, according to Jass et al.) and low (type 2, according to Jass et al.) microsatellite instability (MSI-H and MSI-L) since BRAF-mutations and CpG-island methylation, which are frequently detected in these carcinomas, were only very infrequently observed in adenomas [12].

CpG-island-methylation-phenotype (CIMP) describes an epigenetic methylation of CpG islands in promoter regions of the genome, which silences the transcription of genes [13]. Depending on the number of methylated genes, a phenotype with high (CIMP-H) and low methylation (CIMP-L) can be distinguished. Mismatch repair genes (e.g., MLH1, MGMT) are often silenced which leads to microsatellite instability. These molecular changes can be detected in subgroups of serrated polyps: the (traditional) serrated adenoma (TSA) and the sessile serrated adenoma (SSA, which in recent studies is referred to as a “sessile serrated lesion”, see paragraph “sessile serrated adenoma”) [14], indicating that SSAs and TSAs could be the precursor lesions of these cancers. In addition, an aberrant DNA-methylation occurs very early in the development of these lesions [15]. This so-called CIMP-pathway is viewed as a new pathway of sporadic colorectal carcinogenesis. Some authors postulate that this novel pathway accounts for 30% of all sporadic colorectal carcinomas [4, 12].

There is some evidence that the neoplastic progression within this pathway is faster than within the classical adenoma–carcinoma sequence [16, 17]. Recent case reports suggest that the progression of an SSA to a carcinoma may take as little as 8 months [18]. In a larger cohort, a significant association between large serrated polyps and synchronous advanced adenocarcinomas could also be detected [19]. These novel findings have an enormous impact on the clinical management of different serrated polyps [20, 21].

Still, there is a scientific debate about the morphological criteria for the diagnosis of the different serrated polyps. Accordingly, the nomenclature is inconsistent and partly confusing because different terms are used synonymously (e.g., sessile serrated adenoma/sessile serrated lesion/sessile serrated polyp). It is, therefore, not surprising that serrated precursor lesions are still misdiagnosed and categorized wrongly. Misdiagnosis might lead to an inappropriate therapy and follow-up care. The potential for malignant progression of these lesions is still not clear and has to be studied in prospective clinical trials with standardized morphological criteria for diagnosis.

A standardized diagnostic nomenclature for the German speaking countries was formulated using 19 selected cases encompassing the whole spectrum of serrated lesions during a consensus meeting of the working group, Gastroenterological Pathology of the German Society for Pathology, on 29 April 2008 in Düsseldorf, Germany. This included an elaborate discussion of the diagnostic criteria.

Diagnostic criteria

Hyperplastic polyp (HP)

HPs are by far the most common serrated polyps (80–90%). They occur most often in the distal part of the colon and rectum. Grossly, these are slightly elevated lesions with a diameter of usually less than 5 mm.

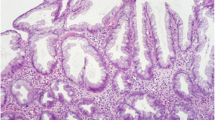

Microscopically, hyperplastic polyps are characterized by elongated crypts with serrated architecture in the upper half of the crypts. Occasionally, these changes can be detected only in the upper third and on the surface of the crypts. This leads to an irregular distension with serration in the upper half of the crypt (Fig. 1; Table 1).

The proliferation in the basal half (non-serrated) of the crypt is regular. The nuclei are small, uniform, and basally placed. There is no crowding of the nuclei in the upper half of the crypt. There is no cytological atypia or intraepithelial neoplasia. In contrast to the sessile serrated adenomas, HPs show no structural or architectural changes. In the literature, three HP subtypes are distinguished according to their cytoplasmic differentiation [22]:

-

1.

microvesicular type (most common)

-

2.

goblet cell type

-

3.

mucin poor type (rarest subtype).

Because it is difficult to distinguish the different subtypes in practice [14] and the clinical relevance of reporting these subtypes is questionable [23], it is not recommended by the working group to subclassify the HPs in routine diagnostics.

The risk of malignant progression for most of the small distally located HPs in the colon and the rectum is very low. In contrast, an HP with a diameter of more than 10 mm and a localization in the proximal colon should be completely removed because some case studies and studies with small cohorts (investigating adenocarcinomas in association with large or giant hyperplastic polyps) suggest that at least some HPs have malignant potential [24, 25]. The occurrence of multiple hyperplastic polyps within the hyperplastic polyposis syndrome is associated with colorectal carcinomas [26–28].

The definition of hyperplastic polyposis is as follows [29]:

-

1.

at least five microscopically confirmed hyperplastic (serrated) polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon, two of which are >1 cm in diameter or

-

2.

every number of hyperplastic (serrated) polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon in patients with a first degree relative diagnosed with hyperplastic polyposis, or

-

3.

more than 30 hyperplastic (serrated) polyps regardless of their size and location.

When one of these criteria is met, the diagnosis, hyperplastic polyposis, should be communicated to the clinician. Recent evidence suggests that there is not only a recessive inherited syndrome but also an autosomal dominant inherited syndrome (serrated pathway syndrome) of hyperplastic polyposis [30].

Traditional serrated adenoma

The traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) is the rarest variant of serrated lesions (1–6%). It has been known since 1990 by the term “serrated adenoma” as a rare variant of adenomas (1%) [31]. Grossly, TSAs are pedunculated or villous polyps, which are more common in the left side (60%) than in the right side of the colon in mostly elderly patients. By definition, the TSA microscopically shows IEN (90% LG-IEN and 10% HG-IEN). Prominent serration and diffuse cytoplasmic eosinophilia with occurrence of so called ectopic crypt formation (ECF) is also detectable in the TSAs. ECF consists of small budding aberrant crypts which lost their orientation towards the lamina muscularis mucosae (Fig. 2; Table 2) [32].

Filiform serrated adenomas with finger-like projections and prominent serrations are an unusual variant of TSA with comparable staining patterns for MGMT, mismatch repair proteins, β-catenin, Ki-67, and p53. They show a predilection for the rectum [33].

Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA)

With a frequency of 15–20%, the SSA is the second most common form of serrated polyps. Grossly, SSAs are flat or slightly elevated lesions typically >5 mm in diameter and localized in the right part of the colon. The microscopic characteristic of the SSA is hyperserration and dilatation of the crypts (with reduced stroma and back-to-back positioning of the dilated crypts) with T- and L-shaped branching at the crypt base. The muscularis mucosae appears thinner than normal and inverted crypts can be found below the muscularis mucosae (so called pseudoinvasion). Other features of the SSA are the presence of mature goblet cells at the base of the crypts, the presence of proliferation in the middle third of the crypt and the detection of slightly enlarged vesicular nuclei with nucleoli [12, 14] (Fig. 3; Table 3).

Sessile serrated adenoma. a Branched crypts (bold arrow), T- and L-shaped bases of the crypts (thin arrows) and columnar dilatation of the crypts (×2.5); b serration reaching to the lower third of the crypts (thin arrows), inverted crypts below the muscularis mucosae (bold arrow) (×2.5) (with permission from PD. Dr. M. Vieth)

According to the consensus, the four most important diagnostic features for SSA are:

-

hyperserration/serration in the lower third of the crypts (with and without branching)

-

T- and L-shaped crypts above the muscularis mucosae

-

inverted crypts (pseudoinvasion) below the muscularis mucosae

-

columnar dilatation in the lower third of the crypts (with or without mucus)Footnote 1

To date, there are no quantitative criteria for the diagnosis of SSA because SSAs have a complex architecture guiding the diagnosis. For pragmatic reasons, the consensus group suggests that the presence of two of the four most important diagnostic features should be present in at least two different crypts to warrant the diagnosis, SSA. The crypts do not have to be next to each other. These diagnostic criteria should also be used for the appendix. This pragmatic approach to the diagnosis of SSAs has been used by the members of the consensus working group with good interobserver concordance, but of course has to be validated in future prospective studies.

There is some controversy about the use of MUC6 staining, which was shown to distinguish HP (MUC6 negative) and SSA (MUC6 positive) in some studies [35]. More recent analyses revealed a relatively high specificity (82%), but relatively low sensitivity for MUC6-expression in SSAs [36]. The consensus group does, therefore, not advise MUC6 as a diagnostic tool for the differentiation of HP and SSA.

It is essential for the diagnosis of SSA that basal mucosa can be evaluated, therefore, when basal parts of the lesion are missing, it is recommended to use the term sessile serrated polyp (SSP). The pathological report should discuss the differential diagnosis and explain why a definite diagnosis could not be determined. The term sessile serrated polyp, however, should be limited to the cases in which basal mucosa is not included in the specimen and should not be used as a “wastebasket diagnosis”.

As already mentioned, SSAs are also referred to as sessile serrated lesions in recent reviews. This new term has been explained by the authors with the fact, that intraepithelial neoplasia is missing in SSA and therefore the term adenoma is not adequate for this entity [14]. The term “lesion” was generated primarily as a term for the gross appearance and may be useful for endoscopy, but we would like to raise some doubt about the appropriateness of the term “sessile serrated lesion” for microscopic diagnosis since it leaves a lot of room for interpretation. The question which of the two terms—sessile serrated adenoma or sessile serrated lesion—will prevail nationally and internationally is still open. The consensus conference recommends the use of the term SSA, which has been included in the most recent German S3 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer [20].

Another controversial issue in diagnosis and nomenclature are those SSAs with intraepithelial neoplasia (Fig. 4). Recently, an adenoma-like IEN (usually top–down) was distinguished from serrated dysplasia (serrated type), which occurs irregularly (in most cases bottom–up) in SSAs (Fig. 4). The international literature uses the term “mixed polyp” for all SSAs with IEN. In the opinion of the consensus group this could lead to a misleading mixture of terms which disregards the malignant potential of SSA with “serrated dysplasia”. Accordingly, it is recommended to temporarily classify this group as “SSA with dysplasia/IEN” (either LG-IEN or HG-IEN). This term allows a clear distinction from mixed polyps with adenoma-like IEN, which might be important because of the different biological behavior of these two lesions.

Mixed polyp

According to the World Health Organization mixed polyps are combinations of conventional (tubular, tubulovillous, and villous) adenomas with different grades of IEN (most commonly top–down morphology) and serrated lesions. These lesions were interpreted as collision tumors in the past (Fig. 5).

The term mixed polyp completely lacks the reference to the inherent IEN and therefore is regarded as potentially misleading by the consensus group because it does not reveal the preinvasive character of the lesions in an adequate manner. Nevertheless, “mixed polyp” is an internationally used and defined term and should be used in the pathological reports for these lesions. It is recommended, however, to first describe the components of the “mixed polyp” and then include the term “mixed polyp” in parentheses (e.g., sessile serrated and tubulovillous adenoma (mixed polyp) with low grade IEN).

There are different forms of mixed polyps according to their components:

-

SSA and TSA

-

SSA and conventional adenoma

-

TSA and conventional adenoma,

-

and as a rare combination: HP and conventional adenoma.

Each of them should be diagnosed with a specification of the grade of IEN: (mixed polyp) with LG-IEN or HG-IEN.

The following terms, however, should not be used: “serrated polyp with abnormal proliferation”, “sawtooth polyp” and “SSA and HP (mixed polyp)”.

Clinical course and relevance

SSA, TSA, and mixed polyps should be removed completely.

When describing mucosectomies, which are performed to remove SSA, TSA or hyperplastic polyps, the microscopic diagnosis should include the status of resection. In case of an incomplete resection or an impossible assessment of the resection status for the pathologist (due to a resection in the piecemeal technique) the pathologist should recommend a control endoscopy to ensure complete removal. Endoscopic follow-up should be performed as stated in the recent S3 guideline “Colorectal Carcinoma” (Table 4). The common hyperplastic polyps of the rectum are not associated with a risk of progression to cancer. Here, the R-status does not need to be described in detail and endoscopic follow-up is not necessary.

Keeping in mind the limited knowledge about the biologic behavior of the serrated lesions, we should increase our efforts to detect and collect cases with proper clinical follow-up, which could be subjected to studies evaluating the malignant potential of these lesions.

Notes

Comment: In a multivariate analysis of 212 serrated lesions the presence of goblet cells at the base of the crypts proved to be an important feature in the discrimination between HP and SSA [34]

References

Morson BC (1962) Precancerous lesions of the colon and rectum. Classification and controversial issues. Jama 179:316–321

Otori K, Oda Y, Sugiyama K et al (1997) High frequency of K-ras mutations in human colorectal hyperplastic polyps. Gut 40:660–663

Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Jass JR et al (1998) Infrequent K-ras codon 12 mutation in serrated adenomas of human colorectum. Gut 42:680–684

Chan TL, Zhao W, Leung SY et al (2003) BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. Cancer Res 63:4878–4881

Preto A, Figueiredo J, Velho S et al (2008) BRAF provides proliferation and survival signals in MSI colorectal carcinoma cells displaying BRAF(V600E) but not KRAS mutations. J Pathol 214:320–327

Velho S, Moutinho C, Cirnes L et al (2008) BRAF, KRAS and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal serrated polyps and cancer: primary or secondary genetic events in colorectal carcinogenesis? BMC Cancer 8:255

Jass JR, Whitehall VL, Young J et al (2002) Emerging concepts in colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology 123:862–876

Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL et al (2004) BRAF mutation is associated with DNA methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. Gut 53:1137–1144

Tateyama H, Li W, Takahashi E et al (2002) Apoptosis index and apoptosis-related antigen expression in serrated adenoma of the colorectum: the saw-toothed structure may be related to inhibition of apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol 26:249–256

Iino H, Jass JR, Simms LA et al (1999) DNA microsatellite instability in hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps: a mild mutator pathway for colorectal cancer? J Clin Pathol 52:5–9

Jass JR, Biden KG, Cummings MC et al (1999) Characterisation of a subtype of colorectal cancer combining features of the suppressor and mild mutator pathways. J Clin Pathol 52:455–460

Jass JR (2007) Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology 50:113–130

Toyota M, Ahuja N, Ohe-Toyota M et al (1999) CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:8681–8686

Kudo S, Lambert R, Allen JI et al (2008) Nonpolypoid neoplastic lesions of the colorectal mucosa. Gastrointest Endosc 68:S3–47

Dong SM, Lee EJ, Jeon ES et al (2005) Progressive methylation during the serrated neoplasia pathway of the colorectum. Mod Pathol 18:170–178

Goldstein NS (2006) Small colonic microsatellite unstable adenocarcinomas and high-grade epithelial dysplasias in sessile serrated adenoma polypectomy specimens: a study of eight cases. Am J Clin Pathol 125:132–145

Lazarus R, Junttila OE, Karttunen TJ et al (2005) The risk of metachronous neoplasia in patients with serrated adenoma. Am J Clin Pathol 123:349–359

Oono Y, Fu K, Nakamura H et al (2009) Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Dig Dis Sci 54:906–909

Li D, Jin C, McCulloch C et al (2009) Association of large serrated polyps with synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol 104:695–702

Schmiegel W, Reinacher-Schick A, Arnold D et al (2008) Update S3-guideline “colorectal cancer” 2008. Z Gastroenterol 46:799–840

Freeman HJ (2008) Heterogeneity of colorectal adenomas, the serrated adenoma, and implications for screening and surveillance. World J Gastroenterol 14:3461–3463

Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC et al (2003) Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol 27:65–81

Noffsinger AE (2009) Serrated polyps and colorectal cancer: new pathway to malignancy. Annu Rev Pathol 4:343–364

Azimuddin K, Stasik JJ, Khubchandani IT et al (2000) Hyperplastic polyps: “more than meets the eye”? Report of sixteen cases. Dis Colon Rectum 43:1309–1313

Warner AS, Glick ME, Fogt F (1994) Multiple large hyperplastic polyps of the colon coincident with adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 89:123–125

Jeevaratnam P, Cottier DS, Browett PJ et al (1996) Familial giant hyperplastic polyposis predisposing to colorectal cancer: a new hereditary bowel cancer syndrome. J Pathol 179:20–25

Renaut AJ, Douglas PR, Newstead GL (2002) Hyperplastic polyposis of the colon and rectum. Colorectal Dis 4:213–215

Torlakovic E, Snover DC (1996) Serrated adenomatous polyposis in humans. Gastroenterology 110:748–755

Hamilton S, Vogelstein B, Kudo S et al (2000) Carcinoma of the colon and rectum. In: Hamilton S, Aaltonen L (eds) Pathology and genetics tumors of the digestive system. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 105–143

Jass JR, Baker K, Zlobec I et al (2006) Advanced colorectal polyps with the molecular and morphological features of serrated polyps and adenomas: concept of a ‘fusion’ pathway to colorectal cancer. Histopathology 49:121–131

Longacre TA, Fenoglio-Preiser CM (1990) Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol 14:524–537

Torlakovic EE, Gomez JD, Driman DK et al (2008) Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) vs. traditional serrated adenoma (TSA). Am J Surg Pathol 32:21–29

Yantiss RK, Oh KY, Chen YT et al (2007) Filiform serrated adenomas: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 31:1238–1245

Wieczorek K, Stolte M, Baretton G et al. (2009) Serrated lesions of the colorectum: morphologic characterisation of a large collective. Der Pathologe Suppl 1:7

Owens SR, Chiosea SI, Kuan SF (2008) Selective expression of gastric mucin MUC6 in colonic sessile serrated adenoma but not in hyperplastic polyp aids in morphological diagnosis of serrated polyps. Mod Pathol 21:660–669

Bartley AN, Thompson PA, Buckmeier JA, Kepler CY, Hsu CH, Snyder MS, Lance P, Bhattacharrya A, Hamilton HR (2010) Expression of gastric pyloric mucin, MUC6, in colorectal serrated polyps. Mod Pathol 23:169–176

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank M. Muders for his help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Members of the consensus conference: F. Autschbach (Heilbronn), S. Baldus (Düsseldorf), Hendrik Bläker (Heidelberg), H. Koch (Bayreuth), C. Langner (Graz), J. Lüttges (Saarbrücken), M. Neid (Bochum), P. Schirrmacher (Heidelberg), A. Tannapfel (Bochum), M. Vieth (Bayreuth).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aust, D.E., Baretton, G.B. & Members of the Working Group GI-Pathology of the German Society of Pathology. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum (hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps)—proposal for diagnostic criteria. Virchows Arch 457, 291–297 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-010-0945-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-010-0945-1