Abstract

The proximal tubule is critical for whole-organism volume and acid–base homeostasis by reabsorbing filtered water, NaCl, bicarbonate, and citrate, as well as by excreting acid in the form of hydrogen and ammonium ions and producing new bicarbonate in the process. Filtered organic solutes such as amino acids, oligopeptides, and proteins are also retrieved by the proximal tubule. Luminal membrane Na+/H+ exchangers either directly mediate or indirectly contribute to each of these processes. Na+/H+ exchangers are a family of secondary active transporters with diverse tissue and subcellular distributions. Two isoforms, NHE3 and NHE8, are expressed at the luminal membrane of the proximal tubule. NHE3 is the prevalent isoform in adults, is the most extensively studied, and is tightly regulated by a large number of agonists and physiological conditions acting via partially defined molecular mechanisms. Comparatively little is known about NHE8, which is highly expressed at the lumen of the neonatal proximal tubule and is mostly intracellular in adults. This article discusses the physiology of proximal Na+/H+ exchange, the multiple mechanisms of NHE3 regulation, and the reciprocal relationship between NHE3 and NHE8 at the lumen of the proximal tubule.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Na+/H+ exchange in biology

Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs) are universally present in prokaryotes, lower eukaryotes, and higher eukaryotes, including fungi, plants, and animals [1]. In prokaryotes, fungi and plants, the transmembrane proton electrochemical gradient (ΔμH+) energizes the extrusion of Na+ from the cytoplasm. Plasma membrane NHEs characterized to date in animal cells utilize the inward Na+ gradient created by the activity of Na+/K+-adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) to extrude H+ against its electrochemical gradient in an electroneutral fashion.

All NHEs are members of the very large superfamily of monovalent cation–proton antiporters (CPA), which is divided phylogenetically in the CPA1, CPA2, and NaT-DC transporter families [1, 2]. Nine NHE isoforms (NHE1–9) belonging to the CPA1 family and having different tissue and subcellular distribution (Table 1) have been described to date in the human genome [1, 3, 4]. In addition, the human genome contains a sperm-specific NHE (a member of the NaT-DC family) with demonstrated NHE activity [1, 5, 6], as well as two genes termed NHA1 and NHA2 (members of the CPA2 family) which are more closely related to prokaryotic Na+/H+ exchangers [1] (Table 1). The expression and function of NHA2 have been recently confirmed [7, 8]. Brett et al. [1] presented an extensive phylogenetic classification of NHEs using 118 eukaryotic NHE genes of the CPA1 family. Based on sequence, cellular location, ion selectivity, and inhibitor specificity, NHEs can be divided into two major subfamilies: intracellular and plasma membrane. The intracellular NHE subfamily can be further divided into three clades: (1) the endosomal/trans-Golgi clade, which includes one of the oldest eukaryotic NHE genes, as well as human NHE6, NHE7, and NHE9; (2) the NHE8-like clade which includes eight animal NHE genes and interestingly shows similarity to Drosophila NHE; (3) the plant vacuolar clade which includes 32 plant NHE genes and the NHE gene of slime mold. The plasma membrane NHE subfamily can be divided into two clades: (1) the recycling clade which includes only animal genes (24 in total), including human NHE3 and NHE5; (2) the resident clade which is restricted to vertebrate NHE genes (25 in total), including human NHE1, NHE2, and NHE4. This classification is extremely useful for understanding differences and similarities in NHE localization, function, and regulation and for identifying the most appropriate models for the study of individual NHEs.

Two members of the NHE family will be discussed here in the context of the renal proximal tubule: NHE3 and NHE8.

Luminal Na+/H+ exchange in proximal tubule physiology

The existence of Na+/H+ exchange activity in the mammalian kidney was first inferred in the 1940s by Pitts and coworkers [9, 10] in a series of studies that, in the words of Gerhard Giebisch, “provided the ground on which modern renal acid-base physiology is based” [11]. Na+/H+ exchange activity was definitively demonstrated three decades later by Murer et al. [12], followed by Kinsella and Aronson [13]. Another decade passed before the first mammalian Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE1, was cloned by Sardet et al. [14]. In the early 1990s, several independent groups identified NHE3 as the main proximal tubular NHE isoform [15–18].

To date, two NHEs have been described at the luminal membrane of proximal tubule cells: NHE3 is predominant in adults [17–19], and NHE8 is highly expressed in neonates [20–22]. A developmental switch between the two transporters has been proposed as part of postnatal renal maturation [22, 23] and will be discussed later in this article. NHE1 and to a lesser extent NHE4 are present at the basolateral membrane [24, 25], but their specific roles in proximal tubule function are not known. Most of what we know today about the molecular physiology and regulation of proximal Na+/H+ exchange pertains to NHE3, which is by far the best-studied luminal isoform.

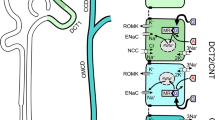

Luminal membrane Na+/H+ exchange in the mammalian proximal tubule mediates the isotonic reabsorption of approximately two thirds of the filtered NaCl and water, the reabsorption of bicarbonate, and the secretion of ammonium (NH4 +) and contributes to the reabsorption of filtered citrate, amino acids, oligopeptides, and proteins. The mechanisms are summarized in Figs. 1 and 2. The regulation of proximal tubule Na+/H+ exchange bears relevance to the regulation of these physiological functions.

Model of how apical Na+/H+ exchange mediates NaCl absorption (left) and luminal acidification (right). The electrochemical driving force (Δμ) is the low cell [Na+] and negative interior voltage generated by the Na+/K+-ATPase. The apical Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 is highlighted in gray. Coupling of Na+/H+ exchange with Cl−/base (B−) exchange and acid (HB) recycling or triple coupling of Na+-sulfate cotransport, sulfate–anion (X−) exchange and Cl−/anion exchange constitutes net apical NaCl entry. The Na+ that enters with organic solutes (Org) also results in net NaCl entry when coupled to paracellular Cl− transport. Basolateral transcellular Cl− exit is achieved via diverse mechanisms (Cl− channel, Na+-dependent Cl−HCO3 − exchange, and KCl cotransport). Luminal acidification by NHE3 titrates filtered HCO3 − which results in HCO3 − absorption. As luminal [HCO3 −] falls with isotonic fluid absorption, luminal Cl− is concentrated (graph in middle panel) along the length of the proximal tubule, which enhances the Δμ for paracellular Cl− diffusion (TF–P, tubular fluid to plasma concentration ratio). The H+ extruded by NHE3 also titrate filtered trivalent citrate to bivalent citrate, which is taken up by the Na+-citrate cotransporter. Citrate reabsorption is tantamount to base equivalent absorption. The metabolism of neutral glutamine (Gln) generates NH4 + (acid) and HCO3 − (base). NH4 + secretion is mediated by NHE3 either by luminal trapping of diffused NH3 or by NH4 + traversing as a substrate. Base exit is mediated by the Na+-HCO3 − cotransporter

Model of how apical Na+/H+ exchange participates in the proximal tubule reabsorption of amino acids, oligopeptides, and proteins. Apical NHE3 provides the H+ used for H+-coupled cotransport of filtered amino acids and oligopeptides. Apical NHE3 also interacts with megalin, which is responsible for receptor-mediated endocytosis of some proteins in the proximal tubule. The interaction with megalin may recruit NHE3 to endocytic vesicles. After endocytosis, NHE3 (and possibly other intracellular NHEs, not shown) utilizes the outward transvesicular Na+ gradient of endocytic vesicles and early endosomes to drive inward movement of protons and endosomal acidification, which is important for further processing of reabsorbed proteins. This model requires further experimental validation

Net apical reabsorption of NaCl involves coupling of Na+/H+ exchange with Cl−/base exchange and acid recycling or triple coupling of Na+-sulfate cotransport, sulfate–anion exchange, and Cl−/anion exchange [26–28] (Fig. 1, left). In addition, the transcellular cotransport of Na+ with organic solutes coupled to paracellular Cl− transport results in net transepithelial NaCl reabsorption [29, 30]. The reabsorption of water results principally from the small osmotic gradient created across the proximal tubular epithelium by NaCl reabsorption. Although water flux can theoretically occur through transcellular and/or paracellular routes, the surface area of the luminal membrane far exceeds that of the paracellular junctions and is endowed with aquaporin water channels [31, 32]. Water is thus mostly reabsorbed via the proximal tubule cell [33, 34].

Proximal tubule bicarbonate reabsorption is in part mediated by apical Na+/H+ exchange, which provides the H+ to titrate luminal filtered HCO3 − [35–37] (Fig. 1, right). The catalytic action of luminal carbonic anhydrase results in generation of CO2, which traverses the apical cell membrane by free diffusion and possibly via water channels, and is reverted to H+ and HCO3 − by intracellular carbonic anhydrase [37, 38]. The resulting intracellular protons are extruded, in part via apical Na+/H+ exchange, thus making HCO3 − available for basolateral transport. In addition, apical Na+/H+ exchange contributes to the generation of new HCO3 − in the proximal tubule by extruding NH4 + (acid equivalent) resulting from the mitochondrial metabolism of glutamine, thereby “freeing” HCO3 − (base equivalent) generated through the same metabolism [39–41]. Reabsorbed as well as intracellularly generated bicarbonate is extruded to the basolateral side mainly via a Na+–HCO3 − cotransport mechanism [35, 42].

Of note, transport of solutes and water by the proximal tubule is not homogenous. The early proximal tubule reabsorbs preferentially HCO3 − and organic solutes, and the resulting concentration of luminal Cl− facilitates downstream paracellular Cl− diffusion [43–46] (Fig. 1, middle). Na+ and water reabsorption by the proximal tubule also varies axially: while fractional reabsorption of volume stays relatively constant, absolute volume reabsorption decreases along the length of the proximal tubule (linear tubular fluid to plasma inulin ratio, middle panel of Fig. 1) [43–45].

Apical Na+/H+ exchange is also important for proximal tubule ammonium secretion, by providing the H+ required for luminal trapping of the freely diffused ammonia (NH3), as well as by directly mediating Na+/NH4 + exchange [40, 41, 47, 48]. In addition, H+ extruded by NHE3 titrate filtered trivalent citrate to its bivalent form, thus facilitating the reabsorption of citrate via a sodium-coupled cotransport mechanism [49–51] (Fig. 1, right).

In accordance with these physiological roles, NHE3-null mice are hypovolemic and hypotensive and have mild metabolic acidosis, decreased renal reabsorption of Na+, fluid, and HCO3 −, and markedly increased mortality when fed a low-salt diet [52]. These abnormalities are improved but not reversed when the expression of NHE3 is rescued by transgenic expression at the other major site of NHE3 action, the small intestine [53, 54].

Finally, apical Na+/H+ exchange plays a role in the proximal tubule reabsorption of filtered organic solutes such as amino acids, oligopeptides, and proteins (Fig. 2). A number of organic solute transporters in vertebrate epithelia with their evolutionary roots in prokaryotes or lower eukaryotes are H+-coupled rather than Na+-coupled [55]. In the proximal tubule, NHE3 generates the proton gradient necessary for H+-coupled reabsorption of filtered amino acids and oligopeptides [56, 57]. The reabsorption of filtered proteins is less well understood. Even the quantity of protein filtered by the normal glomerulus is still a matter of debate, but likely to be significant, with proximal reabsorption being a principal mechanism to render the final urine low in protein [58]. NHE3 may contribute to protein reabsorption by directly interacting with the endocytic receptor megalin at the plasma membrane [59] and by utilizing the outward Na+ gradient of endocytic vesicles and early endosomes to drive inward movement of H+ and endosomal acidification by approximately one pH unit [60–63]. The role of megalin–NHE3 interaction at the plasma membrane is not clear, but from a teleological perspective it can be inferred that NHE3 is brought in the proximity of megalin before endocytosis to provide the machinery for acidification of endocytic vesicles and early endosomes. Experiments showing that megalin mediates the uptake of albumin and that albumin stimulates NHE3 abundance and turnover at the plasma membrane of cultured renal cells are compatible with this model [64, 65]. However, megalin deficiency in both rodents and humans causes low-molecular-weight proteinuria, not albuminuria [66, 67]. The current data are also insufficient to attribute the modest proteinuria of NHE3-null mice [52, 63] strictly to defective proximal tubule endosomal acidification as a de facto conclusion because of the severe extracellular fluid volume depletion and hence the high likelihood of hemodynamically related proteinuria in these animals. In addition, the role of NHE3 in proximal tubule endosomal acidification may be masked by a high degree of functional redundancy, involving the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase and possibly other NHE isoforms with intracellular localization (NHE6–NHE9). Additional research efforts and novel methods are required in the future to solve the quantitative debate over glomerular protein filtration [58] and to ascertain the roles of endocytic receptors, apical NHE3, and intracellular NHE isoforms in tubular protein reabsorption.

Acute vs. chronic regulation of NHE3

NHE3 is responsible for most of proximal tubule NaCl, water, and bicarbonate reabsorption, and a consequence of this high flux transport system is that relatively small percent changes in NHE3 activity can have significant quantitative and functional consequences. It is therefore not surprising that NHE3 is among the most extensively regulated membrane transport proteins, being directly or indirectly influenced by a variety of agonists and physiological conditions [68–70]. A list of factors that regulate NHE3 is presented in Table 2; please note that this list is continually evolving and is by no means exhaustive.

Before delving into further molecular intricacies, it is important to discuss the distinction between acute and chronic NHE3 regulation. Acute (minutes to hours) regulation of NHE3 is better studied, and it could be argued that it is more important for survival, by ensuring the maintenance of volume and acid–base homeostasis in the face of rapid physiological challenges. Acute regulation is via rapid, transient, and often reversible mechanisms (such as changes in phosphorylation, trafficking, or membrane locale) acting on the existing cellular pool of NHE3. Conceptually, acute regulation relies on signaling pathways which may be both saturable and refractory poststimulation, is limited in its response capacity to the use of available transporters, and may overall be more costly for the cellular signaling economy by deflecting essential second messengers and protein kinases from their other intracellular roles. The chronic (hours to days) regulation of NHE3 acts in most cases via slower and more persistent mechanisms (such as transcriptional activation), provides the grounds for long-term adaptation, and may be more important for the pathophysiology of disease—such as hypertension. However, as much as acute and chronic regulations of NHE3 may differ, they are inseparable parts of the same physiological continuum.

Mechanisms of NHE3 regulation

The activity of NHE3 at the apical membrane of proximal tubule epithelial cells can be modulated via a number of mechanisms, including transcriptional [65, 71–74, 77–79] and posttranscriptional [80, 81] regulation, changes in total protein abundance, changes in protein phosphorylation [82–89], trafficking (endocytosis, exocytosis, recycling) [83, 85, 90–92], membrane locale (lipid rafts, microvilli–intermicrovillar clefts) [93–97], and the association of NHE3 with interacting proteins–complexes [70]. Only a brief summary is provided here. More extensive reviews are available [4, 70, 98, 99].

-

1.

Transcriptional regulation. The 5′-flanking promoter region of the NHE3 gene contains multiple putative cis-acting sequences, including glucocorticoid and thyroid response elements, and consensus binding sites for various transcription factors [78, 100–102]. There are several examples of chronic NHE3 regulation by transcriptional activation, including the effects of glucocorticoids [72, 78, 79], thyroid hormones [74], insulin [73], acid [71, 77], and albumin [65]. Increased production of NHE3 transcript is usually, but not always, associated with increased total and plasma membrane NHE3 protein abundance [80, 81].

-

2.

Protein synthesis and degradation. The regulation of total cellular NHE3 protein abundance at the posttranscriptional level is an important, yet underexplored area. The estimated half-life of total NHE3 protein in cultured renal cells is relatively long (∼20 h) [65], and thus posttranscriptional regulation of protein abundance may play a role in chronic but not in acute NHE3 regulation. Cases of diverging regulation of total NHE3 antigen and mRNA have been reported in both rodent kidneys and cultured renal cells [80, 81], but it has been difficult to determine whether this is due to regulation of protein translation, protein degradation, or a combination of the two.

-

3.

Phosphorylation. The C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of NHE3 contains multiple putative phosphorylation sites, mainly phosphoserines, and at least some of these sites are phosphorylated under basal conditions in both renal tissue and cultured cells. While the role of baseline phosphorylation is not clearly defined, there are multiple lines of evidence that additional phosphorylation and/or dephosphorylation events play a role in acute NHE3 regulation [82–88, 103, 104]. The current body of data suggests that changes in NHE3 phosphorylation occur in vivo [88, 105] and are necessary for the regulation of NHE3 by some agonists. For example, protein kinase A (PKA) activation in rats resulted in increased phosphorylation of NHE3 at serines 552 and 605 [105], and mutation of either of these serines in cultured cells abolished NHE3 regulation by the PKA activator 8-Br-cAMP [82]. However, there is evidence in both cultured cells and intact animals that phosphorylation per se is not sufficient for NHE3 regulation [86, 87, 104, 105]. The mechanisms by which phosphorylation alters NHE3 activity are not known. Even though it is theoretically possible that certain phosphorylation patterns may change the conformation and intrinsic transport properties of NHE3, it is more likely that phosphorylation exerts its effects by modulating NHE3 trafficking, association with regulatory proteins, or localization within the plasma membrane. Supporting the role of phosphorylation in NHE3 trafficking, mutation of serines 560 and 613 of Didelphis virginiana NHE3 (equivalent to serines 552 and 605 of rat NHE3) suppressed dopamine-induced PKA-dependent changes in NHE3 plasma membrane abundance [83]. Phosphorylation of another residue conserved across mammalian species, serine 719 of rabbit NHE3, has also been recently shown to regulate NHE3 exocytic insertion into the plasma membrane [89].

-

4.

Trafficking. In cultured renal epithelial cells, native NHE3 is targeted to the apical (luminal) plasma membrane, endocytosed through a clathrin-mediated pathway [106], and then returned in part to the plasma membrane via recycling endosomes [60]. Using epitope-tagged transfected protein, Alexander and coworkers [107] proposed that NHE3 exists in four subpopulations: (a) virtually immobile apical membrane NHE3, anchored to the actin cytoskeleton and dependent on Rho guanosine triphosphatase activity; (b) mobile apical membrane NHE3, not anchored to the cytoskeleton, and more likely to enter coated pits and be endocytosed; (c) rapidly recycling intracellular NHE3, presumably in recycling endosomes; and (d) a separate pool of intracellular NHE3 that exchanges slowly with the other pools. The dynamic balance between NHE3 subpopulations and the interplay between apical membrane insertion, retrieval, and endosomal recycling are what determine the amount of functional NHE3 at the apical membrane. Numerous studies have shown that NHE3 trafficking is regulated at every step, with different agonists or conditions altering NHE3 exocytosis [90–92, 108–110], recycling [65, 111], and endocytosis [83, 85]. Much less is known about the actual pathways and mechanisms involved in regulated NHE3 trafficking. What are the proteins or complexes that recruit NHE3 to exocytic vesicles? What role do posttranslational modifications play in NHE3 trafficking? What triggers NHE3 endocytosis, and what is the molecular decision-making mechanism that sends NHE3 to either recycling or degradation? Are the intracellular pools of NHE3 subject to specific regulation? These and many other questions regarding the trajectory of NHE3 within the proximal tubule cell await exploration.

-

5.

Redistribution along the brush border microvillus. One potential caveat of the cell culture models in which NHE3 has been studied to date is the lack or paucity of a true brush border. Electron microscopy of opossum kidney cells, one of the most used renal epithelial cell lines expressing native NHE3, revealed the presence of scattered microvilli, in much lower numbers than in the native proximal tubule [99, 112]. Do these morphological differences influence NHE3 function and regulation, and, if yes, to what extent? A series of studies by McDonough and colleagues [95–97, 113–116] have shown that different conditions or hormones that regulate NHE3 cause changes in NHE3 redistribution in density gradient fractions, which are interpreted to represent microvilli, intermicrovillar clefts, and endosomes based on cosedimentation of markers. For example, acute parathyroid hormone treatment in rats led to a shift of proximal tubule NHE3 from microvillar to intermicrovillar cleft marker-enriched fractions, and the presence of NHE3 antigen in the intermicrovillar clefts was confirmed by electron microscopy [95]. One interesting possibility is that transporter function may be regulated by redistribution along the microvillus, with NHE3 transport activity decreasing as it approaches the intermicrovillar cleft. Theoretically, this can be a kinetically driven reduction in transport due to less favorable ion gradients (lower sodium concentration and pH), a change in intrinsic transport properties due to interaction with location-specific regulatory factors, or a combination of the two mechanisms (Fig. 3). Ion gradients in the intermicrovillar region have not been directly demonstrated, but the ability of NHEs to generate a measurable spatial pH gradient was shown in vitro by single-cell electrophysiology [117]. Intermicrovillar ion gradients in vivo may be generated by transport processes and may be maintained by the difference in hydrodynamic flow between the axis of the tubular lumen and the intermicrovillar region. In addition to this conceptual model, it is possible that NHE3 in microvilli belongs to the cytoskeleton-anchored membrane NHE3 fraction, as proposed by Alexander and colleagues [107], and that actin binding is lost in intermicrovillar clefts, allowing for internalization. The interaction between NHE3 and megalin was also postulated by Biemesderfer and colleagues [59, 118] to occur in intermicrovillar clefts, where megalin-associated NHE3 is less active and awaiting endocytosis. More studies and novel methods need to be applied to resolve these mechanisms and their relative importance for NHE3 regulation.

-

6.

Changes in membrane locale. The fluid mosaic model of Singer and Nicolson [119] postulated that lipids and proteins diffuse freely and are distributed randomly within cell membranes, with some restraints—such as the tight junction in epithelial cells. The current model adds another level of complexity: discrete membrane microdomains with a higher level of organization and different lipid and protein composition have been proposed to “float” in the surrounding fluid membrane and have been termed lipid rafts [120–122]. There are still many controversies in this field, including lipid raft size, life span, lateral mobility, potential membrane differences between cells in vivo and in culture, and even the appropriateness of various methods used for the study of lipid rafts, but these are beyond the scope of the current discussion. Based on studies using Triton X-100 solubility, density gradients, and manipulation of membrane cholesterol content in cultured renal cells, it was reported that approximately half of apical membrane NHE3 is localized in lipid rafts and that NHE3 activity and trafficking are lipid raft dependent [93, 94]. This may be important for NHE3 regulation, as lipid rafts constitute platforms for the assembly of protein complexes and may contribute to the temporal coordination and spatial compartmentalization of membrane signaling, transport, and trafficking events [123–125].

-

7.

Interacting proteins. The current knowledge about proteins interacting with NHE3 and their role in NHE3 regulation has been recently reviewed with great insight by Donowitz and Li [70]. Some of the best-studied interacting proteins, including calcineurin homologous protein, ezrin, members of the NHE regulatory factor family, and megalin, bind directly to defined regions of the C-terminal putative cytoplasmic domain of NHE3. This region confers regulatory specificity to NHE isoforms: when the cytoplasmic domains were swapped between NHE3 and NHE1, the resulting chimeric proteins were functional Na+/H+ exchangers with regulatory properties similar to those of the exchangers providing the C-terminus [126, 127]. In addition to direct molecular interactions, NHE3 associates in multiprotein complexes and is tethered to the actin cytoskeleton via scaffold and adapter proteins. Specific interaction sequences with multiple protein complexes are likely to govern the strict spatiotemporal coordination necessary for cohesive NHE3 function and regulation [128].

-

8.

Oligomerization. While there are substantial biochemical and structural data consistent with dimer formation of NHE1 [129–132], the data for NHE3 are rather sparse. In cultured renal cells, NHE3 associates in homodimers [133], and the pre-steady-state kinetics of proximal tubule Na+/H+ exchange in rabbit kidney brush border membrane vesicles are compatible with functional cooperativity within NHE3 dimers [134, 135]. Modeling of Na+/H+ transport kinetics using a highly sensitive electrophysiological method [117] suggests that both NHE1 and NHE3 function as coupled homodimers transporting 2Na+/2H+ [136]. The role of dimerization in NHE3 regulation has not been investigated. Theoretically, NHE3 activity could be regulated via changes in dimerization, which in turn may be evoked by alterations in local membrane composition, membrane curvature, or by the competitive interaction of NHE3 monomers with other regulatory proteins. Another exciting theoretical possibility is that NHE3 dimers may constitute units of regulation (an individual regulatory signal reaching one NHE3 molecule affects the function of both molecules within the dimer), thus effectively constituting a biological amplification system for NHE3 regulation.

Theoretical models of how apical Na+/H+ exchange may be regulated by relocation along microvilli in the early proximal tubule. The two models presented are not mutually exclusive and may actually coexist. A kinetically driven reduction in NHE3 activity (left) may be achieved by relocation toward intermicrovillar clefts, where the local ionic gradients, influenced by membrane transport processes and hydrodynamic flow, may be less favorable for Na+/H+ exchange. Alternatively, an intrinsic change in transport property may occur with relocation (right), either by detachment of NHE3 from the actin cytoskeleton or by interaction with other location-specific regulatory factors

An integrated view of NHE3 regulation

The proximal tubule is a phenomenally complex structure, in which myriad cellular processes occur simultaneously—a fact that we sometimes tend to overlook when trying to dissect individual mechanisms. Chances are that, at any given time in the cell, NHE3 activity is affected by many factors, acting via several of the mechanisms categorized above. How is this network coordinated? Are some agonists and signaling pathways more important than others? Can we explain the molecular details of synergism, antagonism, permission, amplification, and interdependence when it comes to the simultaneous regulation of NHE3 by multiple factors—as it is the case in vivo in the proximal tubule?

In order to construct a model of integrated NHE3 regulation, we first need to explore and understand the interactions between individual signaling pathways. For example, Na+/H+ exchange in the proximal tubule and in cultured cells expressing NHE3 is stimulated by glucocorticoids [92, 137–140] and insulin [73, 141, 142] via partly overlapping pathways (Fig. 4). In addition to activation of NHE3 transcription, the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1) appears to act as a central pivot for both pathways [140, 142] and may at least in part explain the permissive effect that glucocorticoids have on insulin action [73, 142]. Another example of complex regulation is NHE3 adaptation to acidosis, which involves multiple signaling pathways and requires the autocrine–paracrine action of endothelin 1, as reviewed by Preisig [143]. A similar permissive effect of glucocorticoids has been described in NHE3 regulation by acid and has been attributed to transcriptional activation [79, 144].

Stimulation of NHE3 by insulin and glucocorticoids. Dashed arrows represent acute regulation (1–2 h), and solid arrows represent chronic regulation (>24 h). Acute regulation of NHE3 by insulin does not involve any of the known mechanisms of insulin signaling or NHE3 regulation. Chronically, insulin stimulates NHE3 via activation of phosphatidyl-inositol-3 kinase (PI3K) and serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1) and by increasing NHE3 transcription. Glucocorticoids acutely stimulate NHE3 exocytic insertion and activate SGK1 in a glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-dependent nongenomic fashion. Chronically, glucocorticoids regulate NHE3 via a genomic mechanism, stimulating both NHE3 and SGK1 transcription. The concerted effects of glucocorticoids and insulin on NHE3 transcription and the central role of SGK1 for both signaling pathways may at least in part explain the permissive effect that glucocorticoids have on insulin action

Many other combinatorial patterns of NHE3 agonists likely exist in vivo, and we are still far from understanding their potential interactions. Although we have come a very long way since Pitts et al. [9, 10] first proposed a Na+/H+ exchange process in the kidney, we only have a distant glimpse of integrated NHE function and regulation.

Luminal NHE8 and its reciprocal relationship to NHE3

Evolution has endowed mammals with multiple NHE genes. Although all NHE proteins studied to date function as Na+/H+ exchangers (or K+/H+ exchangers for some intracellular isoforms), they serve diverse functions in cells and organs. It is intuitive that each NHE isoform must possess some unique properties that justify the maintenance of more than ten different genes through mammalian evolution. Conversely, each isoform possesses sufficient versatility that it can serve more than one function. By the classification of Brett and coworkers [1], NHE8 is an intracellular isoform in most tissues but is also expressed in the proximal tubule brush border [20–22], suggesting that it may serve multiple functions. NHE3 is postulated to serve as a functional exchanger both on the plasma membrane and intracellular vesicles [60]. This type of dual function is becoming increasing common in the NHE field. NHA2, which is much more similar to prokaryotic than eukaryotic NHEs [1], was believed to be purely an intracellular protein [145] until two recent studies demonstrated dual intracellular and plasma membrane distribution in the distal convoluted tubule, erythrocytes, and an islet cell line [7, 8]. It is highly possible that proximal tubular NHE8 serves dual functions.

NHE8 transcript is ubiquitously expressed [20, 21]. In the kidney, NHE8 protein is detected in brush border membrane vesicles by immunoblot and in the proximal apical membrane by immunohistochemistry [20–22] with some predilection for higher expression in the deep cortex [21]. Total cellular NHE8 expression is present but not increased in adult NHE3 null mice [21]. Whether apical membrane NHE8 is increased in the absence of NHE3 has not been determined, but, even if that were the case, NHE8 is insufficient to compensate for the absence of NHE3 in the proximal tubule of adult NHE3-null mice [146].

The demands on the mammalian kidney differ drastically in embryonic to neonatal and subsequently adult life. Current data support a developmental switch of NHE8 and NHE3 in the proximal tubule apical membrane. There is ample precedence for neonatal isoforms of transporters that can more aptly handle the demands of transport during that stage in life [147]. Due consideration will first be given to neonatal proximal acidification. Neonates have lower plasma HCO3 − concentration which is predominantly due to a lower threshold for HCO3 − absorption in the proximal tubule [148, 149]. The proximal tubular HCO3 − threshold in turn is determined by the lower rate of neonatal proximal tubule HCO3 − transport, which is one third that of the equivalent segment in the adult, and not by increased plasma-to-urine back leak [150, 151]. The maturational increase in proximal tubular acidification can be accounted for by the increase in apical membrane Na+/H+ exchange activity [152–155]. Na+/H+ exchange accounts for two thirds of the luminal H+ secretion in the adult [152, 156] and virtually all the luminal acidification in the neonate [152]. In the adult, NHE3 is the predominant Na+/H+ exchanger mediating proximal tubule acidification [19, 52, 157]. Indeed, there is a parallel increase in Na+/H+ exchanger activity [152, 154, 155] and NHE3 protein and transcript with maturation [153]. However, changes in NHE3 expression alone could not explain all the findings.

There is considerable Na+/H+ exchanger activity in neonatal rats despite very low levels of NHE3 protein on brush border membranes [158, 159]. In 30-day-old rats subjected to adrenalectomy to arrest maturation, there is substantive amount of Na+/H+ exchanger activity despite the distinct paucity of NHE3 protein on the apical membrane [159]. In the NHE3 and NHE2 double-knockout mice, there was clearly residual luminal Na+/H+ exchanger activity in the proximal tubule [160]. The collective data support another NHE on the apical membrane, especially in the neonate, that mediates renal acidification. Based on its renal localization, it is likely that NHE8 is the neonatal proximal tubule NHE isoform.

The induction of the NHE8-to-NHE3 developmental switch (Fig. 5) can be intrinsic to the kidney, secondary to circulating factors, or both. To date, evidence exists only for endocrine control. There is a threefold increase in thyroid hormone level and a 25-fold increase in corticosterone level in rat plasma during postnatal maturation [161–164] and these hormonal surges mirror the maturational increase of NHE3 [159]. Perinatal increases in glucocorticoids and thyroid hormone have been proposed by Baum and coworkers [151, 153, 164, 165] to be responsible for the postnatal increase in proximal tubule NHE3 and acidification, and causality is supported by several observations. Administration of glucocorticoids and thyroid hormone prior to the developmental increase in serum levels results in acceleration of the maturation of Na+/H+ exchanger activity and NHE3 mRNA and NHE3 protein abundance [151, 153, 159, 164]. In cultured cells, both glucocorticoids and thyroid hormone directly increase NHE3 transcription and protein abundance [72, 74]. In addition, posttranslational protein trafficking is also involved in the increase in surface NHE3 protein by glucocorticoids [92, 166]. Conversely, preventing the maturational increase in either thyroid hormone or glucocorticoids significantly suppresses the maturational increase in Na+/H+ exchanger activity and brush border membrane NHE3 protein [159, 164]. Experimentally induced hypothyroidism delays the maturational increase in NHE3 and prolongs the expression of neonatal NHE8 [167]. Interaction and complementation between thyroid hormone and glucocorticoid levels have been well described [168–171]. Interestingly, the reduction in NHE3 protein is not accompanied by changes in NHE3 mRNA abundance, once again highlighting the multilevel regulation of NHE3.

Developmental switch of NHE8 and NHE3 at the proximal tubule apical membrane. Maturation signals can be from the systemic circulation, intrinsic to the kidney, or both. While there is parallel increase in total cellular and apical membrane NHE3 upon maturation, the decrease in apical NHE8 in the adult is accompanied by increase in intracellular NHE8

NHE3 protein in total cortex and apical membrane increases concordantly with maturation [153]. In contrast, while apical membrane NHE8 decreases dramatically upon maturation, its level in total cortical membranes is higher in the adult compared to the neonatal proximal tubule [22]. Native NHE8 in cultured cells also has considerable intracellular expression [172]. One possible paradigm is that NHE8 serves primarily as an organellar exchanger in adults, but, in neonates prior to the maturation of NHE3 on the brush border, NHE8 is temporarily “leased” to the apical membrane to perform transepithelial transport.

As mentioned above, Brett and coworkers [1] predicted NHE8 to be an intracellular protein. The function of intracellular NHE8 is unclear at present. Transport characteristics for NHE8 may be more suited for the neonatal proximal tubule than NHE3. Na+ kinetics for example exhibits a higher degree of cooperativity than NHE3 [172] which is what one may expect for an intracellular NHE utilizing vesicular Na+ to drive intravesicular acidification. Nakamura and coworkers [173] found evidence for K+/H+ exchange for NHE8 when reconstituted in proteoliposomes but plasma membrane NHE8 in mammalian cells does not seem to have such properties [172]. Capability of K+/H+ exchange may be intrinsic for the protein but not functional in the plasma membrane environment. A most important and challenging question is what role does intracellular NHE8 play.

Summary

This account covers the role of luminal Na+/H+ exchangers in proximal tubule function and updates selected aspects of the current database on the mechanisms of regulation of NHE3 that are not detailed in other more extensive reviews. Mammals are endowed with multiple NHE genes and have kept this genetic inventory over many millennia without extinguishing any of these sequences. This suggests an “insurance policy” of high redundancy, unique irreplaceable properties of each isoform, or both. Conversely, individual isoforms such as NHE3 participate in extremely diverse functions, such as those described here at the lumen of the proximal tubule. Comparable to its scope of function, the levels of regulation of NHE3 are astoundingly broad—and this is just NHE3 in the proximal tubule, our hors d'oeuvre so to speak, in this field. One has not even begun to consider all the other NHE isoforms in all other nephron segments. The database is of course still very much empty and awaits discovery. NHEs provide a myriad of functions critical for renal physiology in each segment—transport of solutes such as NH4 + within the complex architecture of the medullary, the role of intracellular NHEs for organellar function, nontransport functions as plasma membrane platforms for protein assembly—tasks immense enough to fill several generations of investigators.

The authors took the liberty to linguistically interpret this molecularly guided tour along the nephron conceived by the editors as one that places equal emphasis on the molecule as well as the nephron. There is no doubt that the awesome power of recombinant DNA techniques has spawned a revolution and explosion of knowledge on renal physiology with unprecedented speed and scope; an effect whose momentum will not stall but rather continue to accelerate. All this is triumphant news for the renal physiologist. However, it will be deceiving to assume and believe that the understanding of individual molecules in exquisite detail and precision automatically begets the understanding of tubular, renal, and whole-organism biology. There is a hierarchy from individual molecules to the cell, epithelia, nephron, kidney, and eventually for a physiologist, the organism. At each level of this pyramid, new complexities, patterns, and laws emerge. Such properties cannot be studied and understood when outfitted solely with knowledge derived from a different level. A translated citation of Claude Bernard embodies this spirit eloquently: “We must appreciate that when we break up an organism by taking the different components apart it is only for the sake of convenient experimentation and by no means because we consider them as separate entities. Indeed when we wish to ascribe to a physiologic property its significance we must always refer it to the whole organism and draw any conclusions only in relation to the effect of this property on the organism as a whole.”

References

Brett CL, Donowitz M, Rao R (2005) Evolutionary origins of eukaryotic sodium/proton exchangers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288:C223–C239

Chang AB, Lin R, Keith Studley W et al (2004) Phylogeny as a guide to structure and function of membrane transport proteins. Mol Membr Biol 21:171–181

Bobulescu IA, Di Sole F, Moe OW (2005) Na+/H+ exchangers: physiology and link to hypertension and organ ischemia. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14:485–494

Orlowski J, Grinstein S (2004) Diversity of the mammalian sodium/proton exchanger SLC9 gene family. Pflugers Arch 447:549–565

Wang D, Hu J, Bobulescu IA et al (2007) A sperm-specific Na+/H+ exchanger (sNHE) is critical for expression and in vivo bicarbonate regulation of the soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:9325–9330

Wang D, King SM, Quill TA et al (2003) A new sperm-specific Na+/H+ exchanger required for sperm motility and fertility. Nat Cell Biol 5:1117–1122

Fuster DG, Zhang J, Shi M et al (2008) Characterization of the sodium/hydrogen exchanger NHA2. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:1547–1556

Xiang M, Feng M, Muend S et al (2007) A human Na+/H+ antiporter sharing evolutionary origins with bacterial NhaA may be a candidate gene for essential hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:18677–18681

Pitts RF, Ayer JL, Schiess WA et al (1949) The renal regulation of acid-base balance in man. III. The reabsorption and excretion of bicarbonate. J Clin Invest 28:35–44

Pitts RF, Lotspeich WD (1946) Bicarbonate and the renal regulation of acid base balance. Am J Physiol 147:138–154

Giebisch G (2004) Two classic papers in acid–base physiology: contributions of R. F. Pitts, R. S. Alexander, and W. D. Lotspeich. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287:F864–F865

Murer H, Hopfer U, Kinne R (1976) Sodium/proton antiport in brush-border-membrane vesicles isolated from rat small intestine and kidney. Biochem J 154:597–604

Kinsella JL, Aronson PS (1980) Properties of the Na+–H+ exchanger in renal microvillus membrane vesicles. Am J Physiol 238:F461–F469

Sardet C, Franchi A, Pouyssegur J (1989) Molecular cloning, primary structure, and expression of the human growth factor-activatable Na+/H+ antiporter. Cell 56:271–280

Tse CM, Brant SR, Walker MS et al (1992) Cloning and sequencing of a rabbit cDNA encoding an intestinal and kidney-specific Na+/H+ exchanger isoform (NHE-3). J Biol Chem 267:9340–9346

Orlowski J, Kandasamy RA, Shull GE (1992) Molecular cloning of putative members of the Na/H exchanger gene family. cDNA cloning, deduced amino acid sequence, and mRNA tissue expression of the rat Na/H exchanger NHE-1 and two structurally related proteins. J Biol Chem 267:9331–9339

Biemesderfer D, Pizzonia J, Abu-Alfa A et al (1993) NHE3: a Na+/H+ exchanger isoform of renal brush border. Am J Physiol 265:F736–F742

Amemiya M, Loffing J, Lotscher M et al (1995) Expression of NHE-3 in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubule and thick ascending limb. Kidney Int 48:1206–1215

Wu MS, Biemesderfer D, Giebisch G et al (1996) Role of NHE3 in mediating renal brush border Na+–H+ exchange. Adaptation to metabolic acidosis. J Biol Chem 271:32749–32752

Goyal S, Vanden Heuvel G, Aronson PS (2003) Renal expression of novel Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE8. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284:F467–F473

Goyal S, Mentone S, Aronson PS (2005) Immunolocalization of NHE8 in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288:F530–F538

Becker AM, Zhang J, Goyal S et al (2007) Ontogeny of NHE8 in the rat proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293:F255–F261

Baum M (2008) Developmental changes in proximal tubule NaCl transport. Pediatr Nephrol 23:185–194

Chambrey R, St John PL, Eladari D et al (2001) Localization and functional characterization of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE4 in rat thick ascending limbs. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281:F707–F717

Pizzonia JH, Biemesderfer D, Abu-Alfa AK et al (1998) Immunochemical characterization of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE4. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275:F510–F517

Preisig PA, Rector FC Jr (1988) Role of Na+–H+ antiport in rat proximal tubule NaCl absorption. Am J Physiol 255:F461–F465

Aronson PS (1996) Role of ion exchangers in mediating NaCl transport in the proximal tubule. Kidney Int 49:1665–1670

Aronson PS, Giebisch G (1997) Mechanisms of chloride transport in the proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273:F179–F192

Alpern RJ, Howlin KJ, Preisig PA (1985) Active and passive components of chloride transport in the rat proximal convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest 76:1360–1366

Chantrelle BM, Cogan MG, Rector FC Jr (1985) Active and passive components of NaCl absorption in the proximal convoluted tubule of the rat kidney. Miner Electrolyte Metab 11:209–214

Nielsen S, Smith BL, Christensen EI et al (1993) CHIP28 water channels are localized in constitutively water-permeable segments of the nephron. J Cell Biol 120:371–383

Nielsen S, Marples D, Frokiaer J et al (1996) The aquaporin family of water channels in kidney: an update on physiology and pathophysiology of aquaporin-2. Kidney Int 49:1718–1723

Preisig PA, Berry CA (1985) Evidence for transcellular osmotic water flow in rat proximal tubules. Am J Physiol 249:F124–F131

Schnermann J, Chou CL, Ma T et al (1998) Defective proximal tubular fluid reabsorption in transgenic aquaporin-1 null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:9660–9664

Alpern RJ (1990) Cell mechanisms of proximal tubule acidification. Physiol Rev 70:79–114

Preisig PA, Ives HE, Cragoe EJ Jr et al (1987) Role of the Na+/H+ antiporter in rat proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption. J Clin Invest 80:970–978

Boron WF (2006) Acid–base transport by the renal proximal tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:2368–2382

DuBose TD Jr (1990) Reclamation of filtered bicarbonate. Kidney Int 38:584–589

Halperin ML, Ethier JH, Kamel KS (1990) The excretion of ammonium ions and acid base balance. Clin Biochem 23:185–188

Nagami GT (1989) Ammonia production and secretion by the proximal tubule. Am J Kidney Dis 14:258–261

Weiner ID, Hamm LL (2007) Molecular mechanisms of renal ammonia transport. Annu Rev Physiol 69:317–340

Preisig PA, Alpern RJ (1991) Basolateral membrane H/HCO3 transport in renal tubules. Kidney Int 39:1077–1086

Liu FY, Cogan MG (1984) Axial heterogeneity in the rat proximal convoluted tubule. I. Bicarbonate, chloride, and water transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 247:F816–F821

Maddox DA, Gennari FJ (1985) Load dependence of HCO3 and H2O reabsorption in the early proximal tubule of the Munich-Wistar rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 248:F113–F121

Maddox DA, Gennari FJ (1987) The early proximal tubule: a high-capacity delivery-responsive reabsorptive site. Am J Physiol 252:F573–F584

Schild L, Giebisch G, Green R (1988) Chloride transport in the proximal renal tubule. Annu Rev Physiol 50:97–110

Kinsella JL, Aronson PS (1981) Interaction of NH4+ and Li+ with the renal microvillus membrane Na+–H+ exchanger. Am J Physiol 241:C220–C226

Nagami GT (1988) Luminal secretion of ammonia in the mouse proximal tubule perfused in vitro. J Clin Invest 81:159–164

Brennan S, Hering-Smith K, Hamm LL (1988) Effect of pH on citrate reabsorption in the proximal convoluted tubule. Am J Physiol 255:F301–F306

Sekine T, Cha SH, Hosoyamada M et al (1998) Cloning, functional characterization, and localization of a rat renal Na+-dicarboxylate transporter. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275:F298–F305

Chen XZ, Shayakul C, Berger UV et al (1998) Characterization of a rat Na+-dicarboxylate cotransporter. J Biol Chem 273:20972–20981

Schultheis PJ, Clarke LL, Meneton P et al (1998) Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat Genet 19:282–285

Woo AL, Noonan WT, Schultheis PJ et al (2003) Renal function in NHE3-deficient mice with transgenic rescue of small intestinal absorptive defect. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284:F1190–F1198

Noonan WT, Woo AL, Nieman ML et al (2005) Blood pressure maintenance in NHE3-deficient mice with transgenic expression of NHE3 in small intestine. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288:R685–R691

Daniel H, Spanier B, Kottra G et al (2006) From bacteria to man: archaic proton-dependent peptide transporters at work. Physiology 21:93–102

Daniel H, Rubio-Aliaga I (2003) An update on renal peptide transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284:F885–F892

Watanabe C, Kato Y, Ito S et al (2005) Na+/H+ exchanger 3 affects transport property of H+/oligopeptide transporter 1. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 20:443–451

Comper WD, Haraldsson B, Deen WM (2008) Resolved: normal glomeruli filter nephrotic levels of albumin. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:427–432

Biemesderfer D, Nagy T, DeGray B et al (1999) Specific association of megalin and the Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 in the proximal tubule. J Biol Chem 274:17518–17524

D’Souza S, Garcia-Cabado A, Yu F et al (1998) The epithelial sodium–hydrogen antiporter Na+/H+ exchanger 3 accumulates and is functional in recycling endosomes. J Biol Chem 273:2035–2043

Gekle M (2005) Renal tubule albumin transport. Annu Rev Physiol 67:573–594

Gekle M, Drumm K, Mildenberger S et al (1999) Inhibition of Na+–H+ exchange impairs receptor-mediated albumin endocytosis in renal proximal tubule-derived epithelial cells from opossum. J Physiol 520:709–721

Gekle M, Volker K, Mildenberger S et al (2004) NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger supports proximal tubular protein reabsorption in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287:F469–F473

Zhai XY, Nielsen R, Birn H et al (2000) Cubilin- and megalin-mediated uptake of albumin in cultured proximal tubule cells of opossum kidney. Kidney Int 58:1523–1533

Klisic J, Zhang J, Nief V et al (2003) Albumin regulates the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 in OKP cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:3008–3016

Leheste JR, Rolinski B, Vorum H et al (1999) Megalin knockout mice as an animal model of low molecular weight proteinuria. Am J Pathol 155:1361–1370

Kantarci S, Al-Gazali L, Hill RS et al (2007) Mutations in LRP2, which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause Donnai-Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat Genet 39:957–959

Hayashi H, Szaszi K, Grinstein S (2002) Multiple modes of regulation of Na+/H+ exchangers. Ann N Y Acad Sci 976:248–258

Bobulescu IA, Moe OW (2006) Na+/H+ exchangers in renal regulation of acid–base balance. Semin Nephrol 26:334–344

Donowitz M, Li X (2007) Regulatory binding partners and complexes of NHE3. Physiol Rev 87:825–872

Laghmani K, Borensztein P, Ambuhl P et al (1997) Chronic metabolic acidosis enhances NHE-3 protein abundance and transport activity in the rat thick ascending limb by increasing NHE-3 mRNA. J Clin Invest 99:24–30

Baum M, Amemiya M, Dwarakanath V et al (1996) Glucocorticoids regulate NHE-3 transcription in OKP cells. Am J Physiol 270:F164–F169

Klisic J, Hu MC, Nief V et al (2002) Insulin activates Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 3: biphasic response and glucocorticoid dependence. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283:F532–F539

Cano A, Baum M, Moe OW (1999) Thyroid hormone stimulates the renal Na/H exchanger NHE3 by transcriptional activation. Am J Physiol 276:C102–C108

Yonemura K, Cheng L, Sacktor B et al (1990) Stimulation by thyroid hormone of Na+–H+ exchange activity in cultured opossum kidney cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 258:F333–F338

Azuma KK, Balkovetz DF, Magyar CE et al (1996) Renal Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms and their regulation by thyroid hormone. Am J Physiol 270:C585–C592

Horie S, Moe O, Yamaji Y et al (1992) Role of protein kinase C and transcription factor AP-1 in the acid-induced increase in Na/H antiporter activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:5236–5240

Kandasamy RA, Orlowski J (1996) Genomic organization and glucocorticoid transcriptional activation of the rat Na+/H+ exchanger Nhe3 gene. J Biol Chem 271:10551–10559

Ambuhl PM, Yang X, Peng Y et al (1999) Glucocorticoids enhance acid activation of the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3). J Clin Invest 103:429–435

Di Sole F, Cerull R, Babich V et al (2008) Short- and long-term A3 adenosine receptor activation inhibits the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 activity and expression in opossum kidney cells. J Cell Physiol 216:221–233

Turban S, Wang XY, Knepper MA (2003) Regulation of NHE3, NKCC2, and NCC abundance in kidney during aldosterone escape phenomenon: role of NO. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285:F843–F851

Zhao H, Wiederkehr MR, Fan L et al (1999) Acute inhibition of Na/H exchanger NHE-3 by cAMP. Role of protein kinase a and NHE-3 phosphoserines 552 and 605. J Biol Chem 274:3978–3987

Hu MC, Fan L, Crowder LA et al (2001) Dopamine acutely stimulates Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE3) endocytosis via clathrin-coated vesicles: dependence on protein kinase A-mediated NHE3 phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 276:26906–26915

Peng Y, Moe OW, Chu T et al (1999) ETB receptor activation leads to activation and phosphorylation of NHE3. Am J Physiol 276:C938–C945

Collazo R, Fan L, Hu MC et al (2000) Acute regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 by parathyroid hormone via NHE3 phosphorylation and dynamin-dependent endocytosis. J Biol Chem 275:31601–31608

Wiederkehr MR, Zhao H, Moe OW (1999) Acute regulation of Na/H exchanger NHE3 activity by protein kinase C: role of NHE3 phosphorylation. Am J Physiol 276:C1205–C1217

Wiederkehr MR, Di Sole F, Collazo R et al (2001) Characterization of acute inhibition of Na/H exchanger NHE-3 by dopamine in opossum kidney cells. Kidney Int 59:197–209

Kocinsky HS, Girardi AC, Biemesderfer D et al (2005) Use of phospho-specific antibodies to determine the phosphorylation of endogenous Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 at PKA consensus sites. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289:F249–F258

Sarker R, Gronborg M, Cha B et al (2008) CK2 binds to the C-terminus of NHE3 and stimulates NHE3 basal activity by phosphorylating a separate site in NHE3. Mol Biol Cell 19:3859–3870

Yang X, Amemiya M, Peng Y et al (2000) Acid incubation causes exocytic insertion of NHE3 in OKP cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279:C410–C419

Peng Y, Amemiya M, Yang X et al (2001) ET(B) receptor activation causes exocytic insertion of NHE3 in OKP cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280:F34–F42

Bobulescu IA, Dwarakanath V, Zou L et al (2005) Glucocorticoids acutely increase cell surface Na+/H+ exchanger-3 (NHE3) by activation of NHE3 exocytosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289:F685–F691

Akhter S, Kovbasnjuk O, Li X et al (2002) Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 3 is in large complexes in the center of the apical surface of proximal tubule-derived OK cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283:C927–C940

Murtazina R, Kovbasnjuk O, Donowitz M et al (2006) Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 activity and trafficking are lipid Raft-dependent. J Biol Chem 281:17845–17855

Yang LE, Maunsbach AB, Leong PK et al (2004) Differential traffic of proximal tubule Na+ transporters during hypertension or PTH: NHE3 to base of microvilli vs. NaPi2 to endosomes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287:F896–F906

Leong PK, Yang LE, Lin HW et al (2004) Acute hypotension induced by aortic clamp vs PTH provokes distinct proximal tubule Na+ transporter redistribution patterns. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287:R878–R885

Yang LE, Zhong H, Leong PK et al (2003) Chronic renal injury-induced hypertension alters renal NHE3 distribution and abundance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284:F1056–F1065

Moe OW (1999) Acute regulation of proximal tubule apical membrane Na/H exchanger NHE-3: role of phosphorylation, protein trafficking, and regulatory factors. J Am Soc Nephrol 10:2412–2425

McDonough AA, Biemesderfer D (2003) Does membrane trafficking play a role in regulating the sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 in the proximal tubule? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12:533–541

Cano A (1996) Characterization of the rat NHE3 promoter. Am J Physiol 271:F629–F636

Malakooti J, Sandoval R, Amin MR et al (2006) Transcriptional stimulation of the human NHE3 promoter activity by PMA: PKC independence and involvement of the transcription factor EGR-1. Biochem J 396:327–336

Malakooti J, Memark VC, Dudeja PK et al (2002) Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the human Na(+)/H(+) exchanger NHE3 promoter. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282:G491–G500

Kurashima K, Yu FH, Cabado AG et al (1997) Identification of sites required for down-regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 activity by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem 272:28672–28679

Yip JW, Ko WH, Viberti G et al (1997) Regulation of the epithelial brush border Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 stably expressed in fibroblasts by fibroblast growth factor and phorbol esters is not through changes in phosphorylation of the exchanger. J Biol Chem 272:18473–18480

Kocinsky HS, Dynia DW, Wang T et al (2007) NHE3 phosphorylation at serines 552 and 605 does not directly affect NHE3 activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293:F212–F218

Chow CW, Khurana S, Woodside M et al (1999) The epithelial Na(+)/H(+) exchanger, NHE3, is internalized through a clathrin-mediated pathway. J Biol Chem 274:37551–37558

Alexander RT, Furuya W, Szaszi K et al (2005) Rho GTPases dictate the mobility of the Na/H exchanger NHE3 in epithelia: role in apical retention and targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:12253–12258

Lee-Kwon W, Kawano K, Choi JW et al (2003) Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates brush border Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) activity by increasing its exocytosis by an NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 278:16494–16501

Choi JW, Lee-Kwon W, Jeon ES et al (2004) Lysophosphatidic acid induces exocytic trafficking of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger 3 by E3KARP-dependent activation of phospholipase C. Biochim Biophys Acta 1683:59–68

du Cheyron D, Chalumeau C, Defontaine N et al (2003) Angiotensin II stimulates NHE3 activity by exocytic insertion of the transporter: role of PI 3-kinase. Kidney Int 64:939–949

Kurashima K, Szabo EZ, Lukacs G et al (1998) Endosomal recycling of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 isoform is regulated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 273:20828–20836

Leiderman L, Tucker J, Dennis V (1989) Characterization of proliferation and differentiation of opossum kidney cells in a serum-free defined medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 25:881–886

Yang LE, Leong PK, McDonough AA (2007) Reducing blood pressure in SHR with enalapril provokes redistribution of NHE3, NaPi2, and NCC and decreases NaPi2 and ACE abundance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293:F1197–F1208

Yang LE, Leong PK, Ye S et al (2003) Responses of proximal tubule sodium transporters to acute injury-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284:F313–F322

Yip KP, Tse CM, McDonough AA et al (1998) Redistribution of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 in proximal tubules induced by acute and chronic hypertension. Am J Physiol 275:F565–F575

Zhang Y, Mircheff AK, Hensley CB et al (1996) Rapid redistribution and inhibition of renal sodium transporters during acute pressure natriuresis. Am J Physiol 270:F1004–F1014

Fuster D, Moe OW, Hilgemann DW (2004) Lipid- and mechanosensitivities of sodium/hydrogen exchangers analyzed by electrical methods. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:10482–10487

Biemesderfer D, DeGray B, Aronson PS (2001) Active (9.6 S) and inactive (21 S) oligomers of NHE3 in microdomains of the renal brush border. J. Biol. Chem. 276:10161–10167

Singer SJ, Nicolson GL (1972) The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science 175:720–731

Simons K, Ikonen E (1997) Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 387:569–572

Brown DA, London E (1998) Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 14:111–136

Zajchowski LD, Robbins SM (2002) Lipid rafts and little caves. Compartmentalized signalling in membrane microdomains. Eur J Biochem 269:737–752

Brown DA, Rose JK (1992) Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell 68:533–544

Edidin M (2003) The state of lipid rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 32:257–283

Matko J, Szollosi J (2002) Landing of immune receptors and signal proteins on lipid rafts: a safe way to be spatio-temporally coordinated? Immunol Lett 82:3–15

Cabado AG, Yu FH, Kapus A et al (1996) Distinct structural domains confer cAMP sensitivity and ATP dependence to the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 isoform. J Biol Chem 271:3590–3599

Yun CH, Tse CM, Donowitz M (1995) Chimeric Na+/H+ exchangers: an epithelial membrane-bound N-terminal domain requires an epithelial cytoplasmic C-terminal domain for regulation by protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:10723–10727

Moe OW (2003) Scaffolds: Orchestrating proteins to achieve concerted function. Kidney Int 64:1916–1917

Hisamitsu T, Pang T, Shigekawa M et al (2004) Dimeric interaction between the cytoplasmic domains of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 revealed by symmetrical intermolecular cross-linking and selective co-immunoprecipitation. Biochemistry 43:11135–11143

Hisamitsu T, Ben Ammar Y, Nakamura TY et al (2006) Dimerization is crucial for the function of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1. Biochemistry 45:13346–13355

Green J, Yamaguchi DT, Kleeman CR et al (1988) Cytosolic pH regulation in osteoblasts. Interaction of Na+ and H+ with the extracellular and intracellular faces of the Na+/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol 92:239–261

Moncoq K, Kemp G, Li X et al (2008) Dimeric structure of human Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 overproduced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 283:4145–4154

Fafournoux P, Noel J, Pouyssegur J (1994) Evidence that Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms NHE1 and NHE3 exist as stable dimers in membranes with a high degree of specificity for homodimers. J Biol Chem 269:2589–2596

Otsu K, Kinsella J, Sacktor B et al (1989) Transient state kinetic evidence for an oligomer in the mechanism of Na+–H+ exchange. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:4818–4822

Otsu K, Kinsella JL, Heller P et al (1993) Sodium dependence of the Na(+)–H(+) exchanger in the pre-steady state. Implications for the exchange mechanism. J Biol Chem 268:3184–3193

Fuster D, Moe OW, Hilgemann DW (2008) Steady-state function of the ubiquitous mammalian Na/H exchanger (NHE1) in relation to dimer coupling models with 2Na/2H stoichiometry. J Gen Physiol 132:465–480

Baum M, Moe OW, Gentry DL et al (1994) Effect of glucocorticoids on renal cortical NHE-3 and NHE-1 mRNA. Am J Physiol 267:F437–F442

Baum M, Cano A, Alpern RJ (1993) Glucocorticoids stimulate Na+/H+ antiporter in OKP cells. Am J Physiol 264:F1027–F1031

Wang D, Sun H, Lang F et al (2005) Activation of NHE3 by dexamethasone requires phosphorylation of NHE3 at Ser663 by SGK1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289:C802–C810

Wang D, Zhang H, Lang F et al (2007) Acute activation of NHE3 by dexamethasone correlates with activation of SGK1 and requires a functional glucocorticoid receptor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292:C396–C404

Baum M (1987) Insulin stimulates volume absorption in the rabbit proximal convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest 79:1104–1109

Fuster DG, Bobulescu IA, Zhang J et al (2007) Characterization of the regulation of renal Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 by insulin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292:F577–F585

Preisig PA (2007) The acid-activated signaling pathway: starting with Pyk2 and ending with increased NHE3 activity. Kidney Int 72:1324–1329

Kinsella J, Cujdik T, Sacktor B (1984) Na+–H+ exchange activity in renal brush border membrane vesicles in response to metabolic acidosis: the role of glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81:630–634

Battaglino RA, Pham L, Morse LR et al (2008) NHA-oc/NHA2: a mitochondrial cation–proton antiporter selectively expressed in osteoclasts. Bone 42:180–192

Lorenz JN, Schultheis PJ, Traynor T et al (1999) Micropuncture analysis of single-nephron function in NHE3-deficient mice. Am J Physiol 277:F447–F453

Horster M (2000) Embryonic epithelial membrane transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279:F982–F996

Edelmann CM, Soriano JR, Boichis H et al (1967) Renal bicarbonate reabsorption and hydrogen ion excretion in normal infants. J Clin Invest 46:1309–1317

Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM Jr. et al (1979) Late metabolic acidosis: a reassessment of the definition. J Pediatr 95:102–107

Schwartz GJ, Evan AP (1983) Development of solute transport in rabbit proximal tubule. I. HCO-3 and glucose absorption. Am J Physiol 245:F382–F390

Baum M, Quigley R (1991) Prenatal glucocorticoids stimulate neonatal juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubule acidification. Am J Physiol 261:F746–F752

Baum M (1992) Developmental changes in rabbit juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubule acidification. Pediatr Res 31:411–414

Baum M, Biemesderfer D, Gentry D et al (1995) Ontogeny of rabbit renal cortical NHE3 and NHE1: effect of glucocorticoids. Am J Physiol 268:F815–F820

Beck JC, Lipkowitz MS, Abramson RG (1991) Ontogeny of Na/H antiporter activity in rabbit renal brush border membrane vesicles. J Clin Invest 87:2067–2076

Baum M (1990) Neonatal rabbit juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubule acidification. J Clin Invest 85:499–506

Preisig PA, Alpern RJ (1988) Chronic metabolic acidosis causes an adaptation in the apical membrane Na/H antiporter and basolateral membrane Na(HCO3)3 symporter in the rat proximal convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest 82:1445–1453

Wang T, Yang CL, Abbiati T et al (1999) Mechanism of proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption in NHE3 null mice. Am J Physiol 277:F298–F302

Biemesderfer D, Rutherford PA, Nagy T et al (1997) Monoclonal antibodies for high-resolution localization of NHE3 in adult and neonatal rat kidney. Am J Physiol 273:F289–F299

Shah M, Gupta N, Dwarakanath V et al (2000) Ontogeny of Na+/H+ antiporter activity in rat proximal convoluted tubules. Pediatr Res 48:206–210

Choi JY, Shah M, Lee MG et al (2000) Novel amiloride-sensitive sodium-dependent proton secretion in the mouse proximal convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest 105:1141–1146

Henning SJ (1978) Plasma concentrations of total and free corticosterone during development in the rat. Am J Physiol 235:E451–E456

Walker P, Dubois JD, Dussault JH (1980) Free thyroid hormone concentrations during postnatal development in the rat. Pediatr Res 14:247–249

Henning SJ, Leeper LL, Dieu DN (1986) Circulating corticosterone in the infant rat: the mechanism of age and thyroxine effects. Pediatr Res 20:87–92

Baum M, Dwarakanath V, Alpern RJ et al (1998) Effects of thyroid hormone on the neonatal renal cortical Na+/H+ antiporter. Kidney Int 53:1254–1258

Shah M, Quigley R, Baum M (2000) Maturation of proximal straight tubule NaCl transport: role of thyroid hormone. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278:F596–F602

Loffing J, Lotscher M, Kaissling B et al (1998) Renal Na/H exchanger NHE-3 and Na-PO4 cotransporter NaPi-2 protein expression in glucocorticoid excess and deficient states. J Am Soc Nephrol 9:1560–1567

Gattineni J, Sas D, Dagan A et al (2008) Effect of thyroid hormone on the postnatal renal expression of NHE8. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294:F198–F204

D’Agostino J, Henning SJ (1982) Role of thyroxine in coordinate control of corticosterone and CBG in postnatal development. Am J Physiol 242:E33–E39

Meserve LA, Juarez de Ku LM (1993) Effect of thiouracil-induced hypothyroidism on time course of adrenal response in 15 day old rats. Growth Dev Aging 57:25–30

Mitsuma T, Nogimori T (1982) Effects of adrenalectomy on the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in rats. Horm Metab Res 14:317–319

Stith RD, Reddy YS (1992) Myocardial contractile protein ATPase activities in adrenalectomized and thyroidectomized rats. Basic Res Cardiol 87:519–526

Zhang J, Bobulescu IA, Goyal S et al (2007) Characterization of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE8 in cultured renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293:F761–F766

Nakamura N, Tanaka S, Teko Y et al (2005) Four Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms are distributed to Golgi and post-Golgi compartments and are involved in organelle pH regulation. J Biol Chem 280:1561–1572

Liu F, Gesek FA (2001) alpha(1)-Adrenergic receptors activate NHE1 and NHE3 through distinct signaling pathways in epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280:F415–F425

Nord EP, Howard MJ, Hafezi A et al (1987) Alpha 2 adrenergic agonists stimulate Na+–H+ antiport activity in the rabbit renal proximal tubule. J Clin Invest 80:1755–1762

Li S, Sato S, Yang X et al (2004) Pyk2 activation is integral to acid stimulation of sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3. J Clin Invest 114:1782–1789

Akiba T, Rocco VK, Warnock DG (1987) Parallel adaptation of the rabbit renal cortical sodium/proton antiporter and sodium/bicarbonate cotransporter in metabolic acidosis and alkalosis. J Clin Invest 80:308–315

Soleimani M, Bookstein C, Singh G et al (1995) Differential regulation of Na+/H+ exchange and H+-ATPase by pH and HCO3 − in kidney proximal tubules. J Membr Biol 144:209–216

Ambuhl PM, Amemiya M, Danczkay M et al (1996) Chronic metabolic acidosis increases NHE3 protein abundance in rat kidney. Am J Physiol 271:F917–F925

Di Sole F, Casavola V, Mastroberardino L et al (1999) Adenosine inhibits the transfected Na+–H+ exchanger NHE3 in Xenopus laevis renal epithelial cells (A6/C1). J Physiol 515(Pt 3):829–842

Di Sole F, Cerull R, Petzke S et al (2003) Bimodal acute effects of A1 adenosine receptor activation on Na+/H+ exchanger 3 in opossum kidney cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 14:1720–1730

Di Sole F, Cerull R, Babich V et al (2004) Acute regulation of Na/H exchanger NHE3 by adenosine A(1) receptors is mediated by calcineurin homologous protein. J Biol Chem 279:2962–2974 Epub 2003 Oct 2921

Drumm K, Kress TR, Gassner B et al (2006) Aldosterone stimulates activity and surface expression of NHE3 in human primary proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTEC). Cell Physiol Biochem 17:21–28

Good DW, George T, Watts BA 3rd (2006) Nongenomic regulation by aldosterone of the epithelial NHE3 Na(+)/H(+) exchanger. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290:C757–C763

Watts BA 3rd, George T, Good DW (2006) Aldosterone inhibits apical NHE3 and HCO3 − absorption via a nongenomic ERK-dependent pathway in medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291:F1005–F1013

Harris PJ, Young JA (1977) Dose-dependent stimulation and inhibition of proximal tubular sodium reabsorption by angiotensin II in the rat kidney. Pflugers Arch 367:295–297

Geibel J, Giebisch G, Boron WF (1990) Angiotensin II stimulates both Na(+)–H+ exchange and Na+/HCO3 − cotransport in the rabbit proximal tubule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:7917–7920

Morduchowicz GA, Sheikh-Hamad D, Dwyer BE et al (1991) Angiotensin II directly increases rabbit renal brush-border membrane sodium transport: presence of local signal transduction system. J Membr Biol 122:43–53

Jourdain M, Amiel C, Friedlander G (1992) Modulation of Na–H exchange activity by angiotensin II in opossum kidney cells. Am J Physiol 263:C1141–C1146

Cano A, Miller RT, Alpern RJ et al (1994) Angiotensin II stimulation of Na–H antiporter activity is cAMP independent in OKP cells. Am J Physiol 266:C1603–C1608

Reilly AM, Harris PJ, Williams DA (1995) Biphasic effect of angiotensin II on intracellular sodium concentration in rat proximal tubules. Am J Physiol 269:F374–F380

Houillier P, Chambrey R, Achard JM et al (1996) Signaling pathways in the biphasic effect of angiotensin II on apical Na/H antiport activity in proximal tubule. Kidney Int 50:1496–1505

Poggioli J, Karim Z, Paillard M (1998) Effect of angiotensin ii on Na+/H+ exchangers of the renal tubule. Nephrologie 19:421–425

Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Blanton RM et al (2005) Transgenic expression of fatty acid transport protein 1 in the heart causes lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 96:225–233

Levine SA, Montrose MH, Tse CM et al (1993) Kinetics and regulation of three cloned mammalian Na+/H+ exchangers stably expressed in a fibroblast cell line. J Biol Chem 268:25527–25535

Winaver J, Burnett JC, Tyce GM et al (1990) ANP inhibits Na(+)–H+ antiport in proximal tubular brush border membrane: role of dopamine. Kidney Int 38:1133–1140

Moe OW, Amemiya M, Yamaji Y (1995) Activation of protein kinase A acutely inhibits and phosphorylates Na/H exchanger NHE-3. J Clin Invest 96:2187–2194

Lamprecht G, Weinman EJ, Yun CH (1998) The role of NHERF and E3KARP in the cAMP-mediated inhibition of NHE3. J Biol Chem 273:29972–29978

Cano A, Preisig P, Alpern RJ (1993) Cyclic adenosine monophosphate acutely inhibits and chronically stimulates Na/H antiporter in OKP cells. J Clin Invest 92:1632–1638

Baum M, Quigley R (1998) Inhibition of proximal convoluted tubule transport by dopamine. Kidney Int 54:1593–1600

Bacic D, Kaissling B, McLeroy P et al (2003) Dopamine acutely decreases apical membrane Na/H exchanger NHE3 protein in mouse renal proximal tubule. Kidney Int 64:2133–2141

Felder CC, Campbell T, Albrecht F et al (1990) Dopamine inhibits Na(+)–H+ exchanger activity in renal BBMV by stimulation of adenylate cyclase. Am J Physiol 259:F297–F303

Hu MC, Quinones H, Moe OW (2000) Chronic inhibition of NHE3 by dopamine (DA) in OKP cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 11(Abstracts Issue):5A

Gomes P, Soares-da-Silva P (2004) Dopamine acutely decreases type 3 Na(+)/H(+) exchanger activity in renal OK cells through the activation of protein kinases A and C signalling cascades. Eur J Pharmacol 488:51–59

Eiam-Ong S, Hilden SA, King AJ et al (1992) Endothelin-1 stimulates the Na+/H+ and Na+/HCO3 − transporters in rabbit renal cortex. Kidney Int 42:18–24

Garcia NH, Garvin JL (1994) Endothelin’s biphasic effect on fluid absorption in the proximal straight tubule and its inhibitory cascade. J Clin Invest 93:2572–2577

Walter R, Helmle-Kolb C, Forgo J et al (1995) Stimulation of Na+/H+ exchange activity by endothelin in opossum kidney cells. Pflugers Arch 430:137–144

Chu TS, Peng Y, Cano A et al (1996) Endothelin(B) receptor activates NHE-3 by a Ca2+-dependent pathway in OKP cells. J Clin Invest 97:1454–1462

Laghmani K, Preisig PA, Moe OW et al (2001) Endothelin-1/endothelin-B receptor-mediated increases in NHE3 activity in chronic metabolic acidosis. J Clin Invest 107:1563–1569

Bidet M, Merot J, Tauc M et al (1987) Na+–H+ exchanger in proximal cells isolated from kidney. II. Short-term regulation by glucocorticoids. Am J Physiol 253:F945–F951

Baum M, Quigley R (1993) Glucocorticoids stimulate rabbit proximal convoluted tubule acidification. J Clin Invest 91:110–114

Freiberg JM, Kinsella J, Sacktor B (1982) Glucocorticoids increase the Na+–H+ exchange and decrease the Na+ gradient-dependent phosphate-uptake systems in renal brush border membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79:4932–4936

Kapus A, Grinstein S, Wasan S et al (1994) Functional characterization of three isoforms of the Na+/H+ exchanger stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. ATP dependence, osmotic sensitivity, and role in cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 269:23544–23552

Nath SK, Hang CY, Levine SA et al (1996) Hyperosmolarity inhibits the Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms NHE2 and NHE3: an effect opposite to that on NHE1. Am J Physiol 270:G431–G441

Ambuhl P, Amemiya M, Preisig PA et al (1998) Chronic hyperosmolality increases NHE3 activity in OKP cells. J Clin Invest 101:170–177

Watts BA 3rd, Good DW (1999) Hyposmolality stimulates apical membrane Na(+)/H(+) exchange and HCO(3)(−) absorption in renal thick ascending limb. J Clin Invest 104:1593–1602

Good DW, Di Mari JF, Watts BA III (2000) Hyposmolality stimulates Na+/H+ exchange and HCO3 − absorption in thick ascending limb via PI 3-kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279:C1443–C1454

Alexander RT, Malevanets A, Durkan AM et al (2007) Membrane curvature alters the activation kinetics of the epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE3. J Biol Chem 282:7376–7384

Gesek FA, Schoolwerth AC (1991) Insulin increases Na(+)–H+ exchange activity in proximal tubules from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol 260:F695–F703

Bobulescu IA, Dubree M, Zhang J et al (2008) Effect of renal lipid accumulation on proximal tubule Na+/H+ exchange and ammonium secretion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294:F1315–F1322

Kim JS, Choi KC, Jeong MH et al (2006) Increased expression of sodium transporters in rats chronically inhibited of nitric oxide synthesis. J Korean Med Sci 21:1–4

Gill RK, Saksena S, Syed IA et al (2002) Regulation of NHE3 by nitric oxide in Caco-2 cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283:G747–G756