Abstract

Background and aims

Many studies have been published that report an association between thymidylate synthase (TS) and response to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy and the overall outcome of patients with gastrointestinal cancer. The results have given rise to the possibility that, by determination of TS levels, the physician may decide if the patient has a potential benefit from fluoropyrimidine-based treatment, similar to measurements of oestrogen receptors in breast cancer. The purpose of this review is to summarize critically the reports on TS measurement in gastrointestinal cancer, focusing on the adjuvant fluoropyrimidine treatment situation.

Methods

We reviewed more than 20 studies that reported the association of TS with the clinical outcome in patients with gastrointestinal cancer who had undergone complete resection of the primary tumour only or were receiving additional adjuvant chemotherapy.

Results

Patients with metastasized disease who expressed high TS levels display a low probability of responding to fluoropyrimidine-based treatment and have a poorer survival rate. Patients with high TS levels who undergo complete surgical resection of the primary tumour also have a poorer prognosis than those with tumours with low TS expression. In contrast to advanced disease and to surgery alone, patients with high TS levels appear to benefit, especially, from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy after complete primary tumour resection, while patients with low TS levels do not.

Conclusion

Patients with gastrointestinal cancers that express high TS levels have a poor prognosis with regard to fluoropyrimidine-based palliative chemotherapy or complete primary tumour resection. In contrast, patients with high TS levels might benefit from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based treatment after primary tumour resection. However, additional prospective studies are mandatory to define the precise role of TS in adjuvant therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal malignancies remain a significant health problem in the western world [1]. Advances in early detection, surgery and multi-modal treatment have contributed to the constantly decreasing death rates during the past decades [1]. Despite complete surgical clearance of the primary tumour (R0 resection), a great portion of patients suffer local or distant recurrence at the onset of their disease, presumably due to disseminated micro-metastases present at the time of surgery [2, 3].

It is well established that adjuvant strategies can improve the outcome of patients with several gastrointestinal malignancies when compared with surgery alone. For instance, adjuvant treatment of colon and rectal cancer, using 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-based adjuvant chemotherapy regimens alone and in combination with local irradiation, respectively, significantly reduces recurrence rates and improves survival [4–6]. With 5-FU-based regional chemotherapy after pancreatic cancer resection, a benefit with regard to the incidence of liver metastases could be demonstrated without impact on the prognosis [7]. A recent large multi-centre European trial revealed a significant benefit from the use of adjuvant 5-FU treatment in comparison to surgery alone or chemo-radiation in patients with pancreatic and peri-ampullary cancers [8]. In contrast, the possible beneficial role of adjuvant treatment in oesophageal and gastric cancers is still discussed controversially [9–12].

Despite the positive impact of adjuvant therapy on the outcome, compared with surgery alone, the majority of patients are treated unnecessarily and include those who would never develop a recurrence, even after surgery only, and those who receive adjuvant treatment but still experience early recurrence. A meta-analysis by Sargent and colleagues revealed that only 11% of all treated patients benefited from adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy compared with surgery alone in stages II and III colon cancer [13]. If one takes quality of life and economic aspects into account, the indication for adjuvant treatment has to be indispensably optimized. This could be done by the more precise selection of patients who would potentially benefit from adjuvant treatment strategies. However, currently, only tumour stage is recommended as a decision factor to initiate adjuvant treatment in colon and rectal cancer [14, 15].

Therefore, additional prognostic and predictive factors are needed to identify the subgroups most likely to profit from adjuvant treatment strategies. This could result in a more individualized tumour-tailored multi-modal treatment, saving resources and omitting unnecessary treatment toxicities, while targeting adjuvant treatment to patients most likely to benefit from such modalities. The aim of the present review is to summarize the results of the importance of thymidylate synthase (TS) expression for the outcome of adjuvant treatment in patients with gastrointestinal cancers.

Thymidylate synthase

TS is a dimeric cytosolic protein that catalyses the methylation of deoxyuridine-5′-monophosphate (dUMP) to deoxythymidine-5′-monophosphate (dTMP) with 5,10-methylene tetrahydrofolate (CH2–THF) as a co-factor (Fig. 1) [16, 17]. This reaction provides the sole intracellular de novo source of thymidylate and is, therefore, one of the rate-limiting steps of DNA synthesis [16]. The anti-tumour effect of 5-FU has been ascribed to a number of mechanisms, including incorporation into DNA and RNA [17]. The main mechanism of 5-FU action, however, is ascribed to the competitive inhibition of TS after conversion to its active metabolite 5-fluoro-deoxyuridine monophosphate (FdUMP), as shown in Fig. 1. Additionally, differences in transport, anabolism and catabolism, as well as apoptotic and anti-apoptotic mechanisms, influence its cytotoxic effect, depending on the cell type [17, 18]. The dose schedule may also be a variable that has to be considered when one is predicting response to 5-FU. Bolus 5-FU, with or without the folate analogue folinic acid, might be more RNA-directed than continuous infusion regimens, which suggests that TS measurements might be less predictive when bolus schedules are used [19].

5-FU metabolism. TS catalyses the methylation of dUMP to dTMP, with CH2–THF as a co-factor, the rate-limiting step of DNA synthesis. After conversion to its active metabolite FdUMP, 5-FU inhibits TS, forming an irreversible complex that includes CH2–THF. Some anti-tumour effects of 5-FU are also ascribed to incorporation into DNA and RNA. DHF dihydrofolate. Adapted in part from Danenberg [16] and Van Triest [17]

Methods to determine TS expression

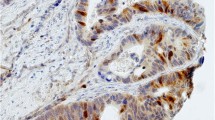

Several methods and assays are available to determine TS levels in cultured cells and tissue samples [20]. These include biochemical assays that determine the catalytic activity or FdUMP ligand-binding [21, 22], mRNA assays, either quantitative or semi-quantitative, when a reference gene is used [23, 24], and immunoblot or immunohistochemistry (IHC) that use monoclonal or polyclonal TS antibodies [25–28].

In the earlier days of TS measurement, immunohistochemical analysis combined several advantages. First, routinely available paraffin-embedded tumour samples could be used. Second, large retrospective studies using archival material could be performed. Third, the morphology and contamination by normal tissue that resulted in low TS expression could be excluded or taken into account. Moreover, possible intratumoral heterogeneity in TS expression could also be assessed [29–31].

However, mRNA assays have recently become more feasible. Fresh specimens can be conveniently stored and shipped at room temperature in RNA-preserving solutions. Using real-time RT-PCR techniques one can also use archival paraffin-embedded samples for TS mRNA quantitation and without the need to use radioactivity [26]. Micro-dissection of the tissue sections prior to TS mRNA quantitation is now established in several laboratories. This might help, in the future, to increase further the accuracy of TS determination using mRNA techniques. A recent meta-analysis suggested that mRNA techniques predicted clinical outcome better than IHC in advanced colorectal cancer [32], although RT-PCR and IHC techniques have been shown to correlate in a great portion of samples when analysed in parallel [26, 33]. One of the reasons might be that TS levels, using immunohistochemistry, are categorized only by a visual grading system based on the intensity (0–3) and the extent (focal–diffuse), whereas TS mRNA quantitation results in numeric values (0–∞). This makes it easier for one to test cut-offs that might be of possible clinical importance [26].

TS as a prognostic and predictive factor in advanced disease

Many pre-clinical studies have demonstrated that high intracellular TS levels correlate with resistance to fluoropyrimidine treatment [18, 20]. These results have been confirmed, so far, by several clinical studies that demonstrate that high TS levels were associated with 5-FU resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer [18, 20]. Independent of the assay method and the systemic 5-FU regimen used, bolus or infusional, high TS levels were associated with 0%–24% response, while response was observed in 49%–67% when low TS levels were present [18]. A similar observation has been made for hepatic arterial infusion that uses fluoropyrimidine-based regimens for isolated non-resectable colorectal liver metastases [23, 34, 35] and other gastrointestinal malignancies, including gastric cancer [36] and primary and secondary liver tumours [37]. A meta-analysis that included 13 studies and a total of 887 cases of advanced colorectal cancer also confirmed that patients with tumours that express high TS levels appear to have a poorer survival rate than those with tumours that express low TS levels [32]. In summary, these studies demonstrate that TS can serve as a predictive and prognostic marker for fluoropyrimidine-based treatment in several advanced gastrointestinal malignancies.

On the basis of these results it seems reasonable to determine TS in the primary tumour for patients who develop metastatic disease at the onset, which avoids the need to biopsy a metastatic lesion. Unfortunately, the studies that were trying to predict response to palliative 5-FU treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer using TS measurement of the primary tumour failed to demonstrate a clear association [38–40]. This observation is, however, not surprising when one considers the fact that several studies have shown that there is no correlation between levels of TS in primary tumours compared with metastatic lesions, the former tending to have higher levels [41, 42]. Additionally, TS may vary, depending on the site of metastasis, with lung and lymph node lesions expressing higher levels than liver metastases [43, 44].

TS as a prognostic factor after surgery only

In 1994, Johnston and colleagues reported for the first time a significant association between TS levels and survival in rectal cancer patients who were undergoing potentially curative resection and being randomized to surgery alone, surgery plus radiation, or surgery plus a 5-FU-consisting adjuvant chemotherapy protocol [29]. Immunohistochemical analysis of paraffin-embedded primary tumour specimens using a monoclonal antibody revealed, for patients with low TS levels, 5-year recurrence-free and overall survival rates of 49% and 60%, respectively, and of only 27% and 40%, respectively, for patients with high TS levels.

The value of TS as prognostic factor for patients with gastrointestinal malignancies who were undergoing potential curative surgery, especially for colorectal cancer, was established thereafter. Several studies demonstrated that high TS levels are associated with poor postoperative outcome after tumour resection in colorectal [28, 30, 45–47], gastric [48] and pancreatic [49] cancer. A meta-analysis that included seven studies and a total of 2,610 patients with localized colorectal cancer supports those findings [32]. However, all those studies included patient subgroups that had received adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. Depending on the influence of adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based treatment in each TS subgroup, a shift in the final outcome cannot be ruled out in all those studies. As shown below, this seems rather likely. The effect of adjuvant 5-FU treatment in the TS subgroups could probably be the reason why no correlation between TS and postoperative outcome was found in three studies of colorectal cancer [31, 50, 51]. In the latter study, there was only a trend for better prognosis for low TS in colon cancer. Besides, if one included patients who were undergoing surgery only and additionally receiving chemotherapy, low TS was infrequent and observed in only 24% of the cases, but high TS accounted for 76%, in contrast to other published studies. An inverse correlation between TS and survival was reported in a very small study that included colorectal cancer patients, where an enzymatic assay was used for TS determination [22], and in a study that included 72 patients who underwent resection of pancreatic cancer [52]. In the latter study, 47 of the 72 patients received various adjuvant chemotherapy, including mitomycin C and cisplatin.

Similarly to most of the above-mentioned studies that included patients who received adjuvant treatment to some extent, the studies that included patients who had undergone only surgery demonstrated that TS is an independent prognostic factor for local recurrence, distant metastasis, and disease-free and overall survival in colorectal cancer [45, 53, 54]. In a small study of 66 patients with resectable colorectal cancer a high TS level was also associated with poorer outcome after oral pretreatment with tegafur–uracil (UFT), a fluoropyrimidine-based agent, prior to surgery [55]. The association between TS and the clinical outcome of patients who undergo surgical resection only is summarized in Table 1. Similar observations have been also made for lung [56] and breast cancer [57]. Additionally, TS levels seem to be associated with tumour stage [28, 29, 53].

Value of TS as a prognostic factor after adjuvant chemotherapy

Studies that included patients who received surgery alone or surgery plus chemotherapy

Johnston and colleagues reported that TS expression is an important independent prognosticator of disease-free and overall survival in patients with rectal cancer [29]. These results were confirmed by several subsequent studies, which demonstrated that high TS levels are associated with poor prognosis in patients who undergo complete primary tumour resection without receiving adjuvant treatment (Table 1). In view of the association of TS in patients with metastasized disease who receive fluoropyrimidine-based treatment, one would assume that patients with low TS levels might also profit from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based therapy after primary tumour resection. However, Johnston and colleagues had already concluded in their study that adjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved the survival rate of patients with high TS levels, whereas it was without effect in patients with low TS levels [29].

In a subgroup analysis of this study, the influence of TS on disease-free and overall survival of 194 patients with Dukes’ B and C rectal cancer treated by either surgery alone or surgery plus chemotherapy was determined. Surprisingly, among the patients with high TS levels, 54% were alive after 5 years, having received surgery plus chemotherapy, compared with only 31% who had undergone surgery alone. In contrast, no significant difference was found among patients with low TS levels (50% vs 57%). The observation that patients with high TS levels from the primary tumour might especially profit from adjuvant 5-FU-based treatment was also reported by several other investigators.

Takenoue and colleagues demonstrated in 141 cases of colon cancer that patients with high TS levels profit from adjuvant oral 5-FU, while this was not the case in the TS-negative group [30]. Another Japanese study, which used oral uracil and UFT for adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer, confirmed those results [31]. In a large Scandinavian study of 862 patients with Dukes’ B and C colorectal cancer it could also be demonstrated that patients (34%) who expressed immunohistochemically the highest TS score significantly benefited from adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy compared with surgery alone, while the others did not, and patients with very low TS levels were even harmed compared to surgery alone [46]. In a recent report about adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer those results could be confirmed. The immunohistochemical study by Hu and colleagues revealed that the risk of death was significantly reduced by chemotherapy among patients with high TS expression [49]. Patients with high TS levels had a median survival time of 19 months when receiving 5-FU-based adjuvant therapy and only 11 months with surgery only. In contrast, the median survival time did not differ significantly in patients with low TS levels when surgery alone was compared with additional adjuvant chemotherapy. The hypothesis that patients with high TS levels might benefit from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based treatment is supported by observations in other studies, which did not reach the level of significance, probably due to the very limited number of patients. In a study by Yamachika and colleagues the 10-year survival rate was increased from 43% to 78% in patients with high TS who had received 5-FU-based chemotherapy, while it was not altered by chemotherapy in patients with low TS levels (86% vs 89%, respectively) [28]. In a Canadian study of UICC II and III colon cancer, relapses were observed in patients with low and high TS in the surgery-only group in 41% and 48%, respectively, and in the adjuvant group in 31% and 30%, respectively [51]. Gastric cancer patients who had received 5-FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy displayed a 5-year overall survival rate of 42% and 57%, respectively, for TS-positive and TS-negative tumours, and 26% and 80%, respectively, when they had undergone surgery only [48]. The studies that investigated the association between TS level and outcome in patients who had undergone surgery alone versus surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy are summarized in Table 2.

Studies that included patients with surgery plus chemotherapy only

When RT-PCR analysis from paraffin-embedded primary tumour tissue was used, it could be demonstrated for UICC stages II and III colorectal cancer that patients with high TS levels displayed a better outcome than patients with low TS who had undergone adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy [26]. It seems possible that patients with high TS obtain an advantage from the adjuvant treatment, while patients with low TS do not. A subgroup analysis of the large Scandinavian trial supports this hypothesis [46]. Edler and colleagues demonstrated that, in particular, patients with very high TS levels (staining intensity 3) benefited from adjuvant treatment, while patients with low TS levels (staining intensity 0–1) had a worse outcome when treated with adjuvant chemotherapy [46]. A tendency towards a worse or no effect on outcome from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based treatment in low TS patients, compared with surgery alone, was also reported in several other studies [28–31, 49], which are summarized in Table 2. The beneficial effect of adjuvant 5-FU-based treatment might also explain the result of a Korean study of gastric cancer patients who had undergone resection [58]. In contrast to the report by Tsujitani and co-workers [48], which demonstrated that TS is also a prognostic marker after resection in gastric cancer, the Korean study revealed no difference in outcome, regardless of the TS level [58]. Another study of only locally advanced pT3pN2 gastric cancer patients, however, could still demonstrate a survival benefit for patients with low-TS tumours who had received 5-FU-based treatment, in comparison with high-TS tumours [59]. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out in that study and the colon cancer studies by Nanni and Sakamoto that patients with high TS levels gained an advantage from adjuvant treatment, while patients with low TS did not [59–61]. The studies about the association of TS with outcome, which included that of patients undergoing surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy, are summarized in Table 3.

The impact of TS expression on prognosis, for patients who had undergone resection of primary colorectal cancer and who had received 5-FU-based adjuvant treatment and experienced tumour recurrence, was analysed in two additional studies. Investigating 100 UICC-stage III colon cancer patients who had received adjuvant 5-FU, Cascinu and colleagues concluded that early tumour recurrence occurs more frequently in immunohistochemically TS over-expressing tumours [62]. The retrospective RT-PCR analyses of 142 primary paraffin-embedded colorectal cancer specimens from patients who had suffered tumour recurrence during or after 1 year of adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy confirmed this observation [63]. Thus, tumour recurrence occurred in the low-TS group (n=102) after a median of 17.6 months (95%CI 13.6–21 months). In contrast, in cases of high TS (n=40) the median time to recurrence was only 11.2 months (95%CI: 8.8–12.6 months). Those observations could suggest that high TS levels might be a positive prognosticator in patients under adjuvant treatment so long as no recurrence occurs; however, once recurrence is established TS switches to become a negative prognosticator.

Concluding remarks

TS plays a key role in fluoropyrimidine resistance and catalyses the rate-limiting step of DNA de novo synthesis [16]. High intratumoral TS levels are believed to confer 5-FU resistance due to inefficient TS inhibition [17]. In the case of advanced unresectable colorectal cancer and other advanced gastrointestinal malignancies, numerous studies have demonstrated the predictive relevance of intratumoral TS for the success of palliative 5-FU treatment and the prognosis of these patients. Several lines of evidence also suggest that TS is an important prognostic marker for survival after complete surgical tumour resection. This might be explained by the fact that TS catalyses the rate-limiting step of DNA de novo synthesis, which is essential for rapid cell proliferation [17]. TS in this setting may be regarded as a biomarker for the proliferative or malignant potential of a tumour. However, the role of intratumoral TS expression in the outcome of adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based treatment after complete surgical resection in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies remains controversial.

In the present review evidence was presented that patients with high TS levels might be the ones that benefit from adjuvant treatment, while patients with low TS levels might not or might even be harmed. Compared with surgery alone, adjuvant chemotherapy prolonged the survival of patients with high TS levels, whereas there was no such survival prolongation by adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with low TS levels in most studies. It is possible that the observed effect might be due to increased efficiency of adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy in patients with primary tumours that express high levels of TS. The hypothesis that high TS might predict the increased efficiency of adjuvant chemotherapy at first glance contrasts with the inverse correlation of TS expression and response to palliative fluoropyrimidine treatment in metastasized gastrointestinal cancers. However, unlike treatment of advanced disease, the survival benefit of adjuvant therapy is mainly attributed to eradication of circulating cancer cells before they become established [2]. The situation of circulating tumour cells, however, is clearly different from the situation of an established tumour mass in many respects. Apart from possible differences in accessibility of the tumour for the drug, in disseminated tumour cells high TS levels might render cells more susceptible to drug-induced cell death via presently unknown mechanisms or may be not dependent on TS inhibition [17, 28, 46].

In view of the fact that only estimated subsets of 10%–20% of the patients obviously profit from the present available adjuvant treatment strategies [13], it would be highly desirable to identify patients that are at risk of developing recurrence in order to focus treatment on them and to avoid therapy for patients who will never suffer a recurrence. Analysis of TS expression might provide a tool to separate patients who are likely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy (high TS) from those who are unlikely to benefit (low TS). However, it is too early to conclude from the presently available studies that the 5-FU treatment currently used should be targeted preferably to the high-TS group.

The possibility that patients with high TS might profit from adjuvant treatment while low TS patients do not should give rise to prospective randomized controlled studies in R0-resected cancer patients that compare the efficacy of adjuvant 5-FU with other potentially active regimens for patients with high and low TS levels [64–66]. Such studies could eventually result in a recommendation for individualization and optimization of adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer on the basis of TS measurement and other markers.

References

Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ (2004) Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin 54:8–29

Midgley R, Kerr D (1999) Colorectal cancer. Lancet 353:391–399

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100:57–70

Rao S, Cunningham D (2003) Adjuvant therapy for colon cancer in the new millennium. Scand J Surg 92:57–64

Saltz LB, Minsky B (2002) Adjuvant therapy of cancers of the colon and rectum. Surg Clin North Am 82:1035–1058

Link KH, Staib L, Kornmann M, Formentini A, Schatz M, Suhr P, Messer P, Rottinger E, Beger HG (2001) Surgery, radio- and chemotherapy for multimodal treatment of rectal cancer. Swiss Surg 7:256–274

Link KH, Leder G, Formentini A, Fortnagel G, Kornmann M, Schatz M, Beger G (1999) Surgery and multimodal treatments in pancreatic cancer—a review on the basis of future multimodal treatment concepts. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 26:10–40

Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, Beger H, Fernandez-Cruz L, Dervenis C, Lacaine F, Falconi M, Pederzoli P, Pap A, Spooner D, Kerr DJ, Buchler MW (2004) A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 350:1200–1210

Lordick F, Stein HJ, Peschel C, Siewert JR (2004) Neoadjuvant therapy for oesophagogastric cancer. Br J Surg 91:540–551

Tak VM, Naunheim KS (2004) Current status of multimodality therapy for esophageal carcinoma. J Surg Res 117:22–29

Yao JC, Mansfield PF, Pisters PW, Feig BW, Janjan NA, Crane C, Ajani JA (2003) Combined-modality therapy for gastric cancer. Semin Surg Oncol 21:223–227

Stahl M (2004) Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy in gastric cancer and carcinoma of the oesophago-gastric junction. Onkologie 27:33–36

Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, Macdonald JS, Labianca R, Haller DG, Shepherd LE, Seitz JF, Francini G (2001) A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med 345:1091–1097

Compton C, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Pettigrew N, Fielding LP (2000) American Joint Committee on Cancer Prognostic Factors Consensus Conference: Colorectal Working Group. Cancer 88:1739–1757

Bast RC Jr, Ravdin P, Hayes DF, Bates S, Fritsche H Jr, Jessup JM, Kemeny N, Locker GY, Mennel RG, Somerfield MR (2000) 2000 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer: clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 19:1865–1878

Danenberg PV (1977) Thymidylate synthetase—a target enzyme in cancer chemotherapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 473:73–92

Van Triest B, Pinedo HM, Giaccone G, Peters GJ (2000) Downstream molecular determinants of response to 5-fluorouracil and antifolate thymidylate synthase inhibitors. Ann Oncol 11:385–391

Bertino JR, Banerjee D (2003) Is the measurement of thymidylate synthase to determine suitability for treatment with 5-fluoropyrimidines ready for prime time? Clin Cancer Res 9:1235–1239

Sobrero AF, Aschele C, Bertino JR (1997) Fluorouracil in colorectal cancer—a tale of two drugs: implications for biochemical modulation. J Clin Oncol 15:368–381

Aschele C, Lonardi S, Monfardini S (2002) Thymidylate synthase expression as a predictor of clinical response to fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy in advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 28:27–47

Spears CP, Shahinian AH, Moran RG, Heidelberger C, Corbett TH (1982) In vivo kinetics of thymidylate synthetase inhibition of 5-fluorouracil-sensitive and -resistant murine colon adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 42:450–456

Sanguedolce R, Brumarescu I, Dardanoni G, Grassadonia A, Vultaggio G, Rausa L (1995) Thymidylate synthase level and DNA-ploidy pattern as possible prognostic factors in human colorectal cancer: a preliminary study. Anticancer Res 15:901–906

Kornmann M, Link KH, Lenz HJ, Pillasch J, Metzger R, Butzer U, Leder GH, Weindel M, Safi F, Danenberg KD, Beger HG, Danenberg PV (1997) Thymidylate synthase is a predictor for response and resistance in hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy. Cancer Lett 118:29–35

Kornmann M, Danenberg KD, Arber N, Beger HG, Danenberg PV, Korc M (1999) Inhibition of cyclin D1 expression in human pancreatic cancer cells is associated with increased chemosensitivity and decreased expression of multiple chemoresistance genes. Cancer Res 59:3505–3511

Johnston PG, Liang CM, Henry S, Chabner BA, Allegra CJ (1991) Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies that localize human thymidylate synthase in the cytoplasm of human cells and tissue. Cancer Res 51:6668–6676

Kornmann M, Schwabe W, Sander S, Kron M, Strater J, Polat S, Kettner E, Weiser HF, Baumann W, Schramm H, Hausler P, Ott K, Behnke D, Staib L, Beger HG, Link KH (2003) Thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase mRNA expression levels: predictors for survival in colorectal cancer patients receiving adjuvant 5-fluorouracil. Clin Cancer Res 9:4116–4124

Okabe H, Tsujimoto H, Fukushima M (1997) The correlation between thymidylate synthase expression and cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil in human cancer cell lines: study using polyclonal antibody against recombinant human thymidylate synthase. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 24:705–712

Yamachika T, Nakanishi H, Inada K, Tsukamoto T, Kato T, Fukushima M, Inoue M, Tatematsu M (1998) A new prognostic factor for colorectal carcinoma, thymidylate synthase, and its therapeutic significance. Cancer 82:70–77

Johnston PG, Fisher ER, Rockette HE, Fisher B, Wolmark N, Drake JC, Chabner BA, Allegra CJ (1994) The role of thymidylate synthase expression in prognosis and outcome of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 12:2640–2647

Takenoue T, Nagawa H, Matsuda K, Fujii S, Nita ME, Hatano K, Kitayama J, Tsuruo T, Muto T (2000) Relation between thymidylate synthase expression and survival in colon carcinoma, and determination of appropriate application of 5-fluorouracil by immunohistochemical method. Ann Surg Oncol 7:193–198

Sugiyama Y, Kato T, Nakazato H, Ito K, Mizuno I, Kanemitsu T, Matsumoto K, Yamaguchi A, Nakai K, Inada K, Tatematsu M (2002) Retrospective study on thymidylate synthase as a predictor of outcome and sensitivity to adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer. Anticancer Drugs 13:931–938

Popat S, Matakidou A, Houlston RS (2004) Thymidylate synthase expression and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 22:529–536

Johnston PG, Lenz HJ, Leichman CG, Danenberg KD, Allegra CJ, Danenberg PV, Leichman L (1995) Thymidylate synthase gene and protein expression correlate and are associated with response to 5-fluorouracil in human colorectal and gastric tumors. Cancer Res 55:1407–1412

Davies MM, Johnston PG, Kaur S, Allen-Mersh TG (1999) Colorectal liver metastasis thymidylate synthase staining correlates with response to hepatic arterial floxuridine. Clin Cancer Res 5:325–328

Bathe OF, Franceschi D, Livingstone AS, Moffat FL, Tian E, Ardalan B (1999) Increased thymidylate synthase gene expression in liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma: implications for chemotherapeutic options and survival. Cancer J Sci Am 5:34–40

Lenz HJ, Leichman CG, Danenberg KD, Danenberg PV, Groshen S, Cohen H, Laine L, Crookes P, Silberman H, Baranda J, Garcia Y, Li J, Leichman L (1996) Thymidylate synthase mRNA level in adenocarcinoma of the stomach: a predictor for primary tumor response and overall survival. J Clin Oncol 14:176–182

Hillenbrand A, Formentini A, Staib L, Sander S, Salonga D, Danenberg K, Danenberg P, Kornmann M (2004) A longterm follow-up study of thymidylate synthase as a predictor for survival of patients with liver tumours receiving hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol 30:407–413

Findlay MP, Cunningham D, Morgan G, Clinton S, Hardcastle A, Aherne GW (1997) Lack of correlation between thymidylate synthase levels in primary colorectal tumours and subsequent response to chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 75:903–909

Paradiso A, Simone G, Petroni S, Leone B, Vallejo C, Lacava J, Romero A, Machiavelli M, De Lena M, Allegra CJ, Johnston PG (2000) Thymidylate synthase and p53 primary tumour expression as predictive factors for advanced colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 82:560–567

Berglund A, Edler D, Molin D, Nordlinder H, Graf W, Glimelius B (2002) Thymidylate synthase and p53 expression in primary tumor do not predict chemotherapy outcome in metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Anticancer Res 22:3653–3659

Aschele C, Debernardis D, Tunesi G, Maley F, Sobrero A (2000) Thymidylate synthase protein expression in primary colorectal cancer compared with the corresponding distant metastases and relationship with the clinical response to 5-fluorouracil. Clin Cancer Res 6:4797–4802

Marsh S, McKay JA, Curran S, Murray GI, Cassidy J, McLeod HL (2002) Primary colorectal tumour is not an accurate predictor of thymidylate synthase in lymph node metastasis. Oncol Rep 9:231–234

Gorlick R, Metzger R, Danenberg KD, Salonga D, Miles JS, Longo GS, Fu J, Banerjee D, Klimstra D, Jhanwar S, Danenberg PV, Kemeny N, Bertino JR (1998) Higher levels of thymidylate synthase gene expression are observed in pulmonary as compared with hepatic metastases of colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 16:1465–1469

Yamada H, Ichikawa W, Uetake H, Shirota Y, Nihei Z, Sugihara K, Hirayama R (2001) Thymidylate synthase gene expression in primary colorectal cancer and metastatic sites. Clin Colorectal Cancer 1:169–173

Edler D, Hallstrom M, Johnston PG, Magnusson I, Ragnhammar P, Blomgren H (2000) Thymidylate synthase expression: an independent prognostic factor for local recurrence, distant metastasis, disease-free and overall survival in rectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 6:1378–1384

Edler D, Glimelius B, Hallstrom M, Jakobsen A, Johnston PG, Magnusson I, Ragnhammar P, Blomgren H (2002) Thymidylate synthase expression in colorectal cancer: a prognostic and predictive marker of benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 20:1721–1728

Allegra CJ, Paik S, Colangelo LH, Parr AL, Kirsch I, Kim G, Klein P, Johnston PG, Wolmark N, Wieand HS (2003) Prognostic value of thymidylate synthase, Ki-67, and p53 in patients with Dukes’ B and C colon cancer: a National Cancer Institute–National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project collaborative study. J Clin Oncol 21:241–250

Tsujitani S, Konishi I, Suzuki K, Oka S, Gomyo Y, Matsumoto S, Hirooka Y, Kaibara N (2000) Expression of thymidylate synthase in relation to survival and chemosensitivity in gastric cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 19:189–195

Hu YC, Komorowski RA, Graewin S, Hostetter G, Kallioniemi OP, Pitt HA, Ahrendt SA (2003) Thymidylate synthase expression predicts the response to 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 9:4165–4171

Allegra CJ, Parr AL, Wold LE, Mahoney MR, Sargent DJ, Johnston P, Klein P, Behan K, O’Connell MJ, Levitt R, Kugler JW, Tria Tirona M, Goldberg RM (2002) Investigation of the prognostic and predictive value of thymidylate synthase, p53, and Ki-67 in patients with locally advanced colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 20:1735–1743

Tomiak A, Vincent M, Earle CC, Johnston PG, Kocha W, Taylor M, Maroun J, Eidus L, Whiston F, Stitt L (2001) Thymidylate synthase expression in stage II and III colon cancer: a retrospective review. Am J Clin Oncol 24:597–602

Takamura M, Nio Y, Yamasawa K, Dong M, Yamaguchi K, Itakura M (2002) Implication of thymidylate synthase in the outcome of patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas and efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy using 5-fluorouracil or its derivatives. Anticancer Drugs 13:75–85

Edler D, Kressner U, Ragnhammar P, Johnston PG, Magnusson I, Glimelius B, Pahlman L, Lindmark G, Blomgren H (2000) Immunohistochemically detected thymidylate synthase in colorectal cancer: an independent prognostic factor of survival. Clin Cancer Res 6:488–492

Lenz HJ, Danenberg KD, Leichman CG, Florentine B, Johnston PG, Groshen S, Zhou L, Xiong YP, Danenberg PV, Leichman LP (1998) p53 and thymidylate synthase expression in untreated stage II colon cancer: associations with recurrence, survival, and site. Clin Cancer Res 4:1227–1234

Tachikawa D, Arima S, Futami K (2000) Immunohistochemical expression of thymidylate synthase as a prognostic factor and as a chemotherapeutic efficacy index in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Anticancer Res 20:4103–4107

Huang CL, Yokomise H, Kobayashi S, Fukushima M, Hitomi S, Wada H (2000) Intratumoral expression of thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with 5-FU-based chemotherapy. Int J Oncol 17:47–54

Nishimura R, Nagao K, Miyayama H, Matsuda M, Baba K, Matsuoka Y, Yamashita H, Fukuda M, Higuchi A, Satoh A, Mizumoto T, Hamamoto R (1999) Thymidylate synthase levels as a therapeutic and prognostic predictor in breast cancer. Anticancer Res 19:5621–5626

Choi J, Lim H, Nam DK, Kim HS, Cho DY, Yi JW, Kim HC, Cho YK, Kim MW, Joo HJ, Lee KB, Kim KB (2001) Expression of thymidylate synthase in gastric cancer patients treated with 5-fluorouracil and doxorubicin-based adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection. Br J Cancer 84:186–192

Suda Y, Kuwashima Y, Tanaka Y, Uchida K, Akazawa S (1999) Immunohistochemical detection of thymidylate synthase in advanced gastric cancer: a prognostic indicator in patients undergoing gastrectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluoropyrimidines. Anticancer Res 19:805–810

Nanni O, Volpi A, Frassineti GL, De Paola F, Granato AM, Dubini A, Zoli W, Scarpi E, Turci D, Oliverio G, Gambi A, Amadori D (2002) Role of biological markers in the clinical outcome of colon cancer. Br J Cancer 87:868–875

Sakamoto J, Hamashima H, Suzuki H, Ito K, Mai M, Saji S, Fukushima M, Matsushita Y, Nakazato H (2003) Thymidylate synthase expression as a predictor of the prognosis of curatively resected colon carcinoma in patients registered in an adjuvant immunochemotherapy clinical trial. Oncol Rep 10:1081–1090

Cascinu S, Graziano F, Valentini M, Catalano V, Giordani P, Staccioli MP, Rossi C, Baldelli AM, Grianti C, Muretto P, Catalano G (2001) Vascular endothelial growth factor expression, S-phase fraction and thymidylate synthase quantitation in node-positive colon cancer: relationships with tumor recurrence and resistance to adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 12:239–244

Kornmann M, Link KH, Galuba I, Ott K, Schwabe W, Hausler P, Scholz P, Strater J, Polat S, Leibl B, Kettner E, Schlichting C, Baumann W, Schramm H, Hecker U, Ridwelski K, Vogt JH, Zerbian KU, Schutze F, Kreuser ED, Behnke D, Beger HG (2002) Association of time to recurrence with thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase mRNA expression in stage II and III colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 6:331–337

Mayer RJ (2004) Two steps forward in the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 350:2406–2408

Douillard JY, Cunningham D, Roth AD, Navarro M, James RD, Karasek P, Jandik P, Iveson T, Carmichael J, Alakl M, Gruia G, Awad L, Rougier P (2000) Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicenter randomized trial. Lancet 355:1041–1047

Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Tabah-Fisch I, de Gramont A (2004) Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350:2343–2351

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Formentini, A., Henne-Bruns, D. & Kornmann, M. Thymidylate synthase expression and prognosis of patients with gastrointestinal cancers receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a review. Langenbecks Arch Surg 389, 405–413 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-004-0510-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-004-0510-y