Abstract

Background

Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay (ARSACS) is a rare early onset neurodegenerative disease that typically results in ataxia, upper motor neuron dysfunction and sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. Dysarthria and dysphagia are anecdotally described as key features of ARSACS but the nature, severity and impact of these deficits in ARSACS are not known. A comprehensive quantitative and qualitative characterization of speech and swallowing function will support diagnostics, provide insights into the underlying pathology, and guide day-to-day clinical management.

Methods

11 consecutive non-Quebec ARSACS patients were recruited, and compared to healthy participants from several published and unpublished cohorts. A comprehensive behavioural assessment including objective acoustic analysis and expert perceptual ratings of motor speech, the Clinical Assessment of Dysphagia in Neurodegeneration (CADN), videofluoroscopy and standardized tests of dysarthria and swallowing related quality of life was conducted.

Results

Speech in this ARSACS cohort is characterized by pitch breaks, prosodic deficits including reduced rate and prolonged intervals, and articulatory deficits. The swallowing profile was characterized by delayed initiation of the swallowing reflex and late epiglottic closure. Four out of ten patients were observed aspirating thin liquids on videofluoroscopy. Patients report that they regularly cough or choke on thin liquids and solids during mealtimes. Swallowing and speech-related quality of life was worse than healthy controls on all domains except sleep.

Conclusions

The dysphagia and dysarthria profile of this ARSACS cohort reflects impaired coordination and timing. Dysphagia contributes to a significant impairment in functional quality of life in ARSACS, and appears to manifest distinctly from other ARSACS dysfunctions such as ataxia or spasticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay (ARSACS) is an early-onset neurodegenerative disorder caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the SACS gene on chromosome 13q11 [1]. ARSACS was originally described in a group of patients in Quebec, Canada. Since discovery of the gene responsible for the disease, however, other cases have been reported globally [2] with a frequency of up to 5% amongst early-onset ataxias [3,4,5]. Individuals with ARSACS usually develop signs before the age of 10 years with a few individuals becoming symptomatic in early adulthood [3, 6]. Clinically ARSACS is characterised by a triad of deficits including cerebellar ataxia, lower limb pyramidal tract signs and axonal-demyelinating sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy [3, 5]. However, not all clinical features are present in mutation carriers, with phenotypic variation extending to mild intellectual disability, retinal disturbance and autonomic symptoms (i.e., urge to void or erectile dysfunction) [3, 5]. The nature, severity and impact of both dysarthria and dysphagia are still poorly characterized in ARASACS, although they are both core to this ataxia as they are in many other early-onset ataxias [7,8,9,10].

Speech and swallowing disturbances are common presentations of cerebellar, pyramidal and brain stem pathologies. Dysarthria often leads to dramatic reductions in quality of life through poor social and employment outcomes [11] and dysphagia can be life threatening in many neurodegenerative diseases following aspiration-related pneumonia [12, 13]. The prevalence, nature, and severity of these two disturbances remain unknown in ARSACS. Here, we present a comprehensive study of speech and swallowing function in non-Quebec individuals with ARSACS, using a quantitative and qualitative protocol including acoustic analysis, videofluoroscopy and quality of life measures.

Detailed examination of these essential life skills in ARSACS will update our clinical description of ARSACS, also outside of Quebec. It will also enhance our understanding of how the underlying neuropathology manifests functionally in this multisystem neurodegenerative disease. Moreover, it might help to yield examples of meaningful patient-focused outcome measures with potential for use in natural history studies and treatment trials, as well as in daily clinical neurorehabilitation in ARSACS.

Methods

Eleven ARSACS (6 female) mutation carriers (mean age = 32.7 ± 13.53 years), range (9–58 years) were recruited consecutively from the Ataxia Clinic at University Clinic, Tübingen, and Essen Hospital, Germany as well as one patient from Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia (see Table 1 for details). No patient had any known relation to Quebec or a Quebec ARSACS patient. SACS mutation carriers were considered to have probable ARSACS if they presented with spastic ataxia or congenital ataxia or spastic paraplegia and two biallelic mutations in SACS per the revised diagnostic criteria [3]. Patients needed to present with signs of ataxia and score > 3/40 points on the Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) [14]. Unless otherwise stated, matched control data were derived from healthy participants recruited in Tübingen Germany. Speech outcomes (both acoustic and listener based) for ARSACS were compared with 34 healthy control participants without neurological illness or physical disability (mean age = 45.9 ± 14.4 years, range 23–69 years, 20 female). The nature of the swallowing outcome measures meant that a combination of unpublished data and previously standardized metrics were used as comparators. Outcomes of the clinical bedside (Clinical Assessment of Dysphagia in Neurodegeneration, CADN) were compared to 78 adults without neurological illness or physical disability (mean age 44.1 years, SD = 18.3; education average 15.5 years, SD = 1.93). Healthy control data for G-SWAL-QOL were derived from 112 adults without neurological illness or physical disability (mean age 44.6 years, SD = 17.1; education average 14.6 years, SD = 2.56). Comparisons for the videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) were made with outcomes published by the tool creators [15]. The study received institutional approval from the Medical Ethics Board, University Hospital Tübingen, Germany (Az. 003/2015BO2) and The University of Melbourne. All patients, or representatives, provided written informed consent.

Clinical, imaging and acoustic assessments

The swallowing assessment protocol included the CADN [16], a translated German version of the Swallowing-Related Quality of Life (G-SWAL-QOL) [17, 18] (both assessments validated for degenerative ataxias) [18] and, only in patients, instrumental imaging assessment of swallowing via a VFSS. Speech was recorded and analyzed perceptually (subjectively) and acoustically (objectively). Disease severity relating to ataxia symptomatology was determined using the clinician derived SARA [14], cognition was assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [19], a 30 item cognitive screener, and activities of daily living using the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [20]. All tests are validated for use in English and German speaking populations.

Swallowing

The CADN is a bedside test of swallowing that quantifies the severity and nature of dysphagia in progressive neurological disorders, including validation in degenerative ataxias [16, 21]. CADN has two components: anamnesis to evaluate feeding-related activities (e.g. chest infections, mealtime managements, and frequency of coughing/choking); the other a consumption component, investigating patients’ risk of penetration/aspiration on a variety of textures and consistencies. Each of the 11 items included in the CADN are rated on a five-point scale with higher numbers indicating increased impairment. The SWAL-QOL was completed by patients to measure swallowing-related quality of life [17, 22].

Ten (out of 11) patients underwent a VFSS. One patient did not undergo VFSS as it was not practically feasible at the time of assessment. Patients were trialed on one teaspoon of puree mixed with contrast agent (first), then 10 and 30 mL of liquid contrast agent, and one bite of bite of dry bread soaked in liquid contrast agent. Data from the exam was analyzed by two trained raters reaching consensus using the Bethlehem Assessment of Swallowing (BAS) [15], a validated VFSS interpretation tool that quantifies function across anatomical sites using a four-point scale, and the Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) [23], a standardized eight-point scale for quantifying the degree of penetration-aspiration observed during VFSS.

Speech

High quality speech and voice samples were acquired using a laptop PC connected to an external sound card (QUAD-CAPTURE USB 2.0 Audio Interface, Roland Corporation, Shizuoka, Japan) and an AKG C520 condenser microphone (AKG Acoustics GmbH, Vienna, Austria). Five speech tasks were elicited in one sitting: (1) unprepared monologue for one minute; (2) reading a brief paragraph with 125 syllables (“Der Nordwind und die Sonne”); (3) a connected speech task that does not require reading—saying the days of the week; (4) a syllable repetition task (i.e., pata) produced as quickly and as clearly as possible for 10 s; and (5) producing a sustained vowel /a:/ on one breath. Tasks (2)–(5) were performed twice to mitigate the effect of unfamiliarity [24, 25]. Tasks fit along a continuum of cognitive automaticity, assisting in dissociation of motor and cognitive deficits [26, 27]. The unprepared monologue task is theorized to be the most complex, with automaticity increasing with the reading, days of the week, syllable repetition and sustained vowel. Speech data were analyzed acoustically using methods previously applied in other progressive neurological disorders [10, 27,28,29]. Acoustic measures of voice quality, vocal control and speech timing were derived using analysis software, PRAAT [30]. Speech samples were rated and described by two trained listeners using a five-point severity scale (0–4). Perceptual parameters included articulation, intonation, voicing, nasality, intelligibility (ability to be understood) and naturalness (degree to which speaker sounds ‘normal’). Expert listeners were blinded to the speakers’ clinical features. Intelligibility was derived from the speech section of the Frenchay Dysarthria Assessment-2 (FDA-2) [31]. Quality of life related to speech was assessed using the Dysarthria Impact Profile (DIP) [32], a self-report questionnaire that explores the impact of disease on the person, the response of others to their speech and general communication. For the single paediatric patient, the DIP was completed by the clinician and patient in partnership. That is, the clinician read the statements and recorded the child’s response.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney converted to standardized t statistics) were used to compare data from all listener derived speech metrics, swallowing data and quality of life questionnaires. Spearman’s Rho was used to examine associations between speech, swallowing, and clinical features including disease severity (SARA) and duration. Only those correlations that differed significantly between ARSACS and controls or scores of ≥ 2 on the VFSS (using the BAS) were examined. The Bonferroni correction method was used to control familywise error rate. Significance was adjusted for multiple comparisons (p = 0.002 (0.05/25) for the speech parameters; p = 0.003 (0.05/17) for swallowing parameters).

Results

Swallowing

Swallowing outcomes differed between patients with ARSACS and healthy controls on the CADN and SWAL-QOL and normative data on the VFSS (Table 2), suggesting that dysphagia is a key feature of the disease. Data derived from CADN part 1 (anamnesis) revealed that 8/11 ARSACS patients presented with moderate or severe mealtime deficits, while 3/11 had sub-clinical deficits, demonstrating that dysphagia is a ubiquitous feature of ARSACS.

Patients reported coughing during mealtimes on solids and liquids several times a week/once a day (7/11). Few patients reported a history of chest infections in the past 12 months (3/11), with only one requiring antibiotics. No patients modified their diet (i.e., thickened fluids, altered consistency) but 4/11 avoided some foods they considered difficult to eat. One patient required positioning at the table during mealtimes. Four out of eleven of patients coughed or presented with an intermittent wet voice with spontaneous clearance when drinking water. Only sub-clinical deficits were observed across the group on puree and biscuit trials with 6/11 patients presenting with either extended oral phase or oral residue post swallow on dry solids.

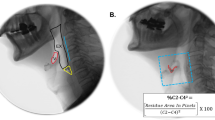

All ARSCAS patients presented with deficits on at least one aspect of swallowing as determined by VFSS (see Fig. 1 for ratings by site and function), thus further supporting the finding that dysphagia is a ubiquitous feature of ARSACS. Across textures (e.g., liquid, solid), patients presented with delayed swallow reflex initiation, disordered epiglottic closure and limited efficiency of second swallow. Patients also showed reduced pharyngeal function on liquid trials. The remaining sites and functions were within normal limits highlighting a specific pattern of swallowing deficits relating to timing and pharyngeal coordination. The mean PAS score across the consistencies was > 4 on liquids (contacts the vocal folds, and is ejected from the airway) and < 2 on puree and bread (within normal limits). Four out of ten patients received a rating of 7 (material enters the airway, passes below the vocal folds, and is not ejected from the trachea despite effort) on the liquid trial, suggesting that 40% of our cohort aspirated on thin liquids. Overall, PAS ratings (scale 1–8) for each consistency were: Liquids = 4.0 ± 2.58; puree = 1.7 ± 0.83; bread = 1.1 ± 0.32; with healthy normative participants = 1.14 ± 0.35 [23] across consistencies.

Consensus ratings from Videofluoroscopy Swallowing Study (VFSS) (Mean ± SD). Increasing values indicate worsening function on scales; normative healthy control data published by creators of VFSS scoring criteria [21]. No control data for Epiglottic closure or efficacy of 2nd swallow

Speech

All patients with ARSACS displayed dysarthria resulting in abnormal naturalness and reduced intelligibility. Overall dysarthria severity was predominantly mild with some speech subsystems more severely affected including prosody and articulation. The speech of ARSACS was characterized by pitch breaks, prolonged intervals, excess loudness variation, vowel distortion, and imprecise consonants (see Table 3 for description of features).

Intelligibility was examined using the intelligibility component of the FDA-2 (scale of 1–9 where higher scores indicate better intelligibility). Subtle but distinct differences were observed between ARSACS patients and healthy controls at word, sentence and general communication levels [word level intelligibility was rated at 7.18 ± 1.47 [ARSACS] and 9.0 ± 0.0 [CONTROLS] (t = − 5.788 p < 0.001)], sentence level at 7.3 ± 0.95 [ARSACS] and 8.94 ± 0.34 [CONTROLS] (t = − 5.256, p < 0.001) and general communication rated at 7.36 ± 0.51 [ARSACS] and 8.97 ± 0.17 [CONTROLS] (t = − 6.304, p < 0.001).

Speech related quality of life was reduced in ARSACS patients. Average scores (± SD) for the five sections of the DIP were (scale of 1–5 where higher scores indicate smaller impact): Section A = The effect of dysarthria on me as a person: 3.54 ± 0.757; Section B = Accepting my dysarthria: 3.51 ± 0.698; Section C = How I feel others react to my speech: 3.57 ± 0.6; Section D = How dysarthria affects my communication with others: 3.56 ± 0.437; Section E = Dysarthria relative to other worries and concerns: 4.67 ± 0.5; Total impact score (out of 225): 174.89 ± 26.87.

Objective analysis of speech via acoustic analysis revealed differences between groups on measures of pitch control (vowel) and timing but not voice quality. The speech of ARSACS patients was slower, with longer and variable pause lengths (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Materials Table A). Deficits in timing were observed across tasks with larger differences observed on the complex (unprepared monologue) rather than simpler connected speech tasks (days of the week).

Acoustic measures of speech. ****p < 0.001; HNR harmonics to noise ratio, SD standard deviation; automated task is days of the week; ms milliseconds; Coefficient of variation (CoV) of fundamental frequency (f0); error bars = SD. Healthy control data were derived from 34 adults without neurological illness or physical disability (mean age = 45.9 ± 14.4 years, range 23–69 years, 20 female)

The relationship between swallowing, speech, disease severity (SARA) and duration and age of disease onset were explored using Spearman’s Rho on those measures that varied significantly between patients with ARSACS and healthy controls (significance adjusted for multiple comparisons with p < 0.003 (p = 16/0.05) for speech and p < 0.004 (p = 12/0.05) for swallowing parameters). All measures failed to reach significance after adjusting for multiple comparisons. However, despite failing to reach significance, several large and meaningful comparisons were observed (where Cohen [33] suggests ‘small’, ‘medium’, and ‘large’ effects are r = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, respectively). Large correlation coefficients were observed between age of disease onset and PAS scores (on liquid) (ρ = 0.681, p = 0.03), SWAL-QOL (eating duration) (ρ = 0.764, p = 0.017), (mental health) (ρ = 0.724, p = 0.027), as well as between disease severity and PAS (liquid) (ρ = 0.64, p = 0.046) and, disease duration and FDA (intelligibility) (ρ = 0.66, p = 0.027).

Discussion

Mutations of the SACS gene cause a progressive neurodegenerative triad of ataxia, upper motor neuron damage and peripheral neuropathy, leading to a varied spectrum of features including ataxic movement deficits in speech and swallowing. Refining the phenotype of this rare recessive disorder will assist in identifying behavioral treatment targets and recognizing those aspects of the disease that may be suitable markers of disease progression or treatment response. To date no in-depth investigation of speech and swallowing in ARSACS has been conducted, neither in Quebec ARSACS patients nor in non-Quebec ARSACS patients. All patients with ARSACS in our cohort presented with swallowing and speech deficits varying from subclinical to severe.

The speech signature of ARSACS is characterized by timing and articulatory deficits, with about half of patients presenting with dysphonia and poor pitch control. Although variations between affected individuals were noted, the predominant features of dysarthria consisted of altered prosody, articulatory breakdowns including imprecise consonants, vowel distortions and prolonged intervals between words. These deficits combine to produce speech that remains largely intelligible but harder to understand than healthy speakers. Patients with ARSACS predominately differ from healthy speakers on measures of timing, with the speech rate decreasing the more complex a speech task appears. Large correlation coefficients were observed between intelligibility and disease duration suggesting a gradual decline in speech post onset, however, prospective longitudinal monitoring is required to elucidate the progressive clinical profile of patients.

Objective measures of speech quantified the size of deficits in speech timing during connected speech and vocal control on sustained vowel tasks. All acoustic measures of timing including speech rate, proportion of silence in each sample and variability of pause length differed between groups, with the more cognitively demanding tasks yielding larger differences between patients and controls. Working on the theory that speech tasks fit on a continuum of automaticity [26, 27], with some stimuli requiring relatively little cognitive planning (e.g., automated tasks—days of the week) and others requiring simultaneous and contemporaneous language formulation and motor planning (e.g., unprepared monologue), this battery highlights the increasing burden complex speech tasks place on producing effective communicative in ARSACS. At the same time, this finding provides insight into the functioning of underlying speech systems in ARSACS, which seem to be impaired not only in terms of motor speech execution per se, but also in the cognitive preprocessing stages of speech that seem to be disturbed in ARSACS. The exact contribution of the cerebellum to linguistic and cognitive processes is not fully understood, however, some aspects of language and speech production appear to be related to cerebellar function including speech timing, sensorimotor integration, articulatory precision and control, vocal fold coordination, and sequencing of output [34].

The speech profile of patients with ARSACS shares some features with other spinocerebellar disorders including ataxia individuals with mutations in the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma (POLG-A) [10] and with Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) [8]. All three autosomal-recessive disorders present with proto-typical deficits in timing, with altered prosody and articulation. These impairments translate to speech that sounds slower, is punctuated by imprecisely produced consonants, and distorted vowels. ARSACS differs from these spinocerebellar disorders on measures of voice quality where POLG-A present with strain-strangled dysphonia [10] and FRDA with hoarseness and breathiness [35]. Although some patients with ARSACS presented with hoarseness, their principal voice deficit was pitch breaks with an absence of resonance issues.

Speech related quality of life in patients with ARSACS was lower than previously reported data from a small group of healthy controls [36] but higher than other patient groups with dysarthria, including those with stroke [37], Parkinson’s disease [38] or POLG-A [10]. These data highlight that the presence of dysarthria does affect quality of life (with patients reporting others react differently to them because of their speech). However, the relative impact compared to other disease groups is difficult to quantify without commensurate knowledge of disease stage and dysarthria severity.

The swallowing profile of ARSACS varied across the cohort, which might be due to several different factors such as the small sample size of the study cohort and also the heterogeneity of the disease per se, which appears to be more heterogeneous in non-Quebec ARSACS patients than in Quebec ARSACS patients [5, 39] t. Most patients presented with mild dysphagia: however, 4/10 aspirated on thin liquids suggesting that some patients are at risk of aspiration pneumonia [40]. The key areas of deficit observed during VFSS relate to deficits in timing. Patients with ARSACS presented with delayed initiation of swallow and disordered pharyngeal function manifesting in poor contraction and bolus flow through the pharynx. Inadequate epiglottic closure and ineffective second swallow were also observed in most patients. These features were reported in the absence of overt deficits in tongue function (i.e. forming and controlling bolus), contrary to findings from other cerebellar ataxias (e.g., Friedreich ataxia [9] or POLG-A [10]). Performance during swallowing trials of thin liquids was considerably worse than during those of solid or puree consistencies, providing further evidence that the swallowing profile of the ARSACS patients studied here is related to timing rather than weakness.

Few patients reported needing assistance during mealtimes, or while drinking, however, 4/11 modified eating and drinking habits to improve their swallow (e.g., avoiding difficult-to-swallow foods). Three patients reported having a chest infection in the 12 months prior to assessment, with one of those requiring antibiotics to clear the infection. Importantly, four patients (patients 1, 3, 5, 10) aspirated on the liquid trial during VFSS. Perhaps due to the small study size, no clear relationship was established between disease duration or severity, and aspiration. However, a significant association was observed between age of onset and the ‘Symptoms’ score of the SWAL-QOL, suggesting that some features of dysphagia are linked to some aspects of the disease profile. The rate of progression of dysphagic symptoms in ARSACS and their relationship to other disease features such as overall disease severity implies that some aspects of swallowing decline at a different rate from other ARSACS-related dysfunctions. The presence of aspiration and the heterogeneous decline of other dysphagic features advocates for universal swallowing screening of all patients with ARSACS irrespective of overall disease function.

Patients with ARSACS reported lower swallowing related quality of life outcomes compared to controls for the majority of domains assessed by the SWAL-QOL, leading to fear and increased burden during mealtimes. However, as was the case for speech, the size of this effect was smaller than has been observed in other progressive disorders in including FRDA [9, 41], Parkinson’s disease [42] or POLG-A [10]. The nature of these deficits focused on prolonged mealtimes, fatigue while eating and the burden dysphagia placed on their lives, highlighting the impact swallowing deficits in ARSACS place on the individual.

Data reported here are derived from 11 patients and require validation in a larger sample. The size of this study and the consecutive nature of the sampling has led to the inclusion of a heterogenous group of participants. Caution should be exercised when interpreting these data in the context of the broader ARSACS population as they may not represent all patients with the disease and might also differ from the—genetically much more homogeneous—Quebec population of ARSACS patients. The methods and data described here provide a framework on which to make decisions about the nature and severity of this multi-systemic spinocerebellar disease. Direct comparison with other hereditary ataxias may also assist in improving differential diagnosis and identification of relative severity of deficits. The test used here may be sensitive to disease progression and treatment response. The acoustic aspects of the speech protocol are known to be stable, reliable and sensitive to change and impairment [24], however, the reliability and sensitivity of other aspects of the assessment protocol require further investigation. Speech and swallowing are two fundamental life skills that are adversely affected by ARSACS. The Food and Drug Administration (USA) have called for investigators and pharmaceutical companies to employ meaningful outcome measures when demonstrating treatment efficacy. The tools described here highlight the role tests of dysarthria and dysphagia can play in patient care. They tap directly into activities that are important to patients and will assist in designing function-based interventional trials [43, 44] and assessment protocols of the future.

References

Engert JC, Berube P, Mercier J et al (2000) ARSACS, a spastic ataxia common in northeastern Quebec, is caused by mutations in a new gene encoding an 11.5-kb ORF. Nat Genet 24(2):120–125

Girard M, Larivière R, Parfitt DA et al (2012) Mitochondrial dysfunction and Purkinje cell loss in autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay (ARSACS). Proc Natl Acad Sci 109(5):1661–1666

Pilliod J, Moutton S, Lavie J et al (2015) New practical definitions for the diagnosis of autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay. Ann Neurol 78(6):871–886

Vermeer S, Meijer RPP, Pijl BJ et al (2008) ARSACS in the Dutch population: a frequent cause of early-onset cerebellar ataxia. Neurogenetics 9(3):207–214

Synofzik M, Soehn AS, Gburek-Augustat J et al (2013) Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix Saguenay (ARSACS): expanding the genetic, clinical and imaging spectrum. Orphanet J Rare Dis 8:41

Ouyang Y, Takiyama Y, Sakoe K et al (2006) Sacsin-related ataxia (ARSACS): Expanding the genotype upstream from the gigantic exon. Neurology 66(7):1103–1104

Isono C, Hirano M, Sakamoto H, Ueno S, Kusunoki S, Nakamura Y (2015) Differential progression of dysphagia in heredity and sporadic ataxias involving multiple systems. Eur Neurol 74(5–6):237–242

Folker JE, Murdoch BE, Cahill LM, Delatycki MB, Corben LA, Vogel AP (2010) Dysarthria in Friedreich’s ataxia: a perceptual analysis. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedia 62(3):97–103

Keage MJ, Corben LC, Delatycki MB, Vogel AP (2017) Dysphagia in Friedreich’s ataxia. Dysphagia 32:626–635

Vogel AP, Rommel N, Oettinger A et al (2017) Speech and swallowing abnormalities in adults with POLG associated ataxia (POLG-A). Mitochondrion 37:1–7

Gibilisco P, Vogel AP (2013) Friedreich ataxia. BMJ 347:f7062

Heemskerk A-W, Roos RA (2012) Aspiration pneumonia and death in Huntington’s disease. PLoS Curr 4:RRN1293

Tsou AY, Paulsen EK, Lagedrost SJ et al (2011) Mortality in Friedreich Ataxia. J Neurol Sci 307(1–2):46–49

Schmitz-Hubsch T, Du Montcel ST, Baliko L et al (2006) Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology 66(11):1717–1720

Scott A, Perry A, Bench J (1998) A study of interrater reliability when using videofluoroscopy as an assessment of swallowing. Dysphagia 13(4):223–227

Vogel AP, Rommel N, Sauer C et al (2017) Clinical assessment of dysphagia in neurodegeneration (CADN): development, validity and reliability of a bedside tool for dysphagia assessment. J Neurol 264(6):1107–1117

McHorney CA, Martin-Harris B, Robbins JA, Rosenbek JC (2006) Clinical validity of the SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcome tools with respect to bolus flow measures. Dysphagia 21(3):141–148

Kraus E-M, Rommel N, Stoll LH, Oettinger A, Vogel AP, Synofzik M (2018) Validation and psychometric properties of the German version of the SWAL-QOL. Dysphagia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9872-5

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V et al (2005) The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(4):695–699

Katz S (1983) Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc 31(12):721–727

Vogel AP, Rommel N, Sauer C, Synofzik M (2016) Clinical assessment of dysphagia in neurodegeneration (CADN): reliability and validity. Eur J Neurol 23:226

Keage MJ, Delatycki M, Corben LA, Vogel AP (2015) A systematic review of self-reported swallowing assessments in progressive neurological disorders. Dysphagia 30(1):27–46

Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL (1996) A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia 11(2):93–98

Vogel AP, Fletcher J, Snyder PJ, Fredrickson A, Maruff P (2011) Reliability, stability, and sensitivity to change and impairment in acoustic measures of timing and frequency. J Voice 25(2):137–149

Vogel AP, Maruff P (2014) Monitoring change requires a rethink of assessment practices in voice and speech. Logop Phoniatr Vocol 39(2):56–61

Vogel AP, Fletcher J, Maruff P (2014) The impact of task automaticity on speech in noise. Speech Commun 65:1–8

Vogel AP, Poole ML, Pemberton H et al (2017) Motor speech signature of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: refining the phenotype. Neurology 89(8):837–844

Rosen KM, Folker JE, Vogel AP, Corben LA, Murdoch BE, Delatycki MB (2012) Longitudinal change in dysarthria associated with Friedreich ataxia: a potential clinical endpoint. J Neurol 259(11):2471–2477

Vogel AP, Shirbin C, Churchyard AJ, Stout JC (2012) Speech acoustic markers of early stage and prodromal Huntington’s disease: a marker of disease onset? Neuropsychologia 50(14):3273–3278

Boersma P (2001) Praat, a system for doing phonetics by computer. Glot Int 5(9/10):341–347

Enderby P, Palmer R (2012) FDA-2: Frenchay Dysarthrie assessment—2. Schulz-Kirchner, Idstein

Walshe M, Peach RK, Miller N (2009) Dysarthria impact profile: development of a scale to measure psychosocial effects. Int J Lang Commun Disord 44(5):693–715

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Mariën P, Ackermann H, Adamaszek M et al (2014) Consensus paper: language and the cerebellum: an ongoing enigma. Cerebellum 13(3):386–410

Vogel AP, Wardrop MI, Folker JE et al (2017) Voice in Friedreich Ataxia. J Voice 31(2):243.e249–243.e219

Letanneux A, Walshe M, Viallet F, Pinto S (2013) The Dysarthria impact profile: a preliminary french experience with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Dis 2013:6

Park S, Theodoros DG, Finch E, Cardell E (2016) Be clear: a new intensive speech treatment for adults with nonprogressive dysarthria. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 25(1):97–110

Theodoros DG, Hill AJ, Russell TG (2016) Clinical and quality of life outcomes of speech treatment for Parkinson’s disease delivered to the home via telerehabilitation: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 25(2):214–232

Baets J, Deconinck T, Smets K et al (2010) Mutations in SACS cause atypical and late-onset forms of ARSACS. Neurology 75(13):1181–1188

Schmidt J, Holas M, Halvorson K, Reding M (1994) Videofluoroscopic evidence of aspiration predicts pneumonia and death but not dehydration following stroke. Dysphagia 9(1):7–11

Vogel AP, Brown SE, Folker JE, Corben LA, Delatycki MB (2014) Dysphagia and swallowing related quality of life in Friedreich ataxia. J Neurol 261(2):392–399

Leow LP, Huckabee M-L, Anderson T, Beckert L (2010) The impact of dysphagia on quality of life in ageing and Parkinson’s disease as measured by the swallowing quality of life (SWAL-QOL) questionnaire. Dysphagia 25(3):216–220

Vogel AP, Folker JE, Poole ML (2014) Treatment for speech disorder in Friedreich ataxia and other hereditary ataxia syndromes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:CD008953

Vogel AP, Keage MJ, Johansson K, Schalling E. Treatment for dysphagia (swallowing difficulties) in hereditary ataxia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(11):CD010169

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ataxia Charlevoix–Saguenay Foundation and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the ERA-NET Cofund action N° 643578. It was supported by the BMBF (01GM1607 to M. S.), under the frame of the E-Rare-3 network PREPARE (to M. S. and C. G.). A. P. V. receives salaried support from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia (Career Development Fellowship ID 1082910), received funding from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation.

Funding

A/Prof Vogel is chief science officer of Redenlab who aided the acoustic analysis. He also receives institutional support from The University of Melbourne. Ms. Rommel, Ms. Stoll, Ms. Kraus, Mr. Oettinger, Dr. Gagnon, Prof. Horger, Dr. Krumm all have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Prof. APV contributed to the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting the manuscript. He also supervised students, led the research team, and obtained funding for the research. Ms. NR contributed to the design of the study, collected data, analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript for intellectual content, and supervision of students. Mr. AO contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Ms. LHS contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Ms. EK contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Dr. CG contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Prof. MH and Dr. PK contributed to administering and interpreting the VFSS and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Prof. DT contributed to patient recruitment and examination, data interpretation and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Prof. Dr. LS and Prof. ES contributed to data interpretation and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. Dr. MS contributed to the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. He also supervised students, led the research team, and obtained funding for the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Prof. Timmann receives funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Mercator Research Center Ruhr and the German Heredoataxia Foundation unrelated to this study. Prof. Storey receives funding from the NIH, unrelated to this study. Prof. Dr. Schöls receives funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG), the European Union and the German Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Foundation unrelated to this study. Dr. Synofzik received honoraria from Actelion pharmaceuticals, unrelated to the current study.

Ethical standards

The study received institutional approval from the Medical Ethics Board, University Hospital Tübingen, Germany (Az. 003/2015BO2) and The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee. All patients, or representatives, provided written informed consent. The project was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vogel, A.P., Rommel, N., Oettinger, A. et al. Coordination and timing deficits in speech and swallowing in autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix–Saguenay (ARSACS). J Neurol 265, 2060–2070 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-8950-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-8950-4