Abstract

Fungal rhinosinusitis (FRS) is uncommon and accounts for 6–12% of culture or histologically proven chronic sinusitis. FRS may be acute or chronic. The aim of this paper was to study the histological features that contribute to the diagnosis and sub typing of FRS, using a retrospective review of all paranasal sinus mucosal biopsies from January 2005 to December 2008. The clinical features, predisposing conditions, imaging findings, and extent of the lesion were noted. The slides were reviewed with hematoxylin and eosin, Gomori’s methenamine silver, and periodic acid Schiff stains. Culture reports were obtained wherever material was subjected to culture. There were 63 biopsies diagnosed as FRS (45.7%) out of 138 biopsies of chronic sinusitis in the study period. The FRS was classified as allergic in 15 (23.8%), chronic non-invasive (sinus mycetoma) in 1 (1.6%), chronic invasive in 10 (15.87%), granulomatous invasive in 19 (30%), and acute fulminant in 18 (28.5%) biopsies or surgical resections. Predisposing conditions were identified in 19 patients with diabetes mellitus as the commonest. Seventeen of the 18 patients with acute fulminant FRS had predisposing conditions. As per the results, the characteristic histological features were allergic mucin in allergic, fungal ball in chronic non-invasive, sparse inflammation and numerous hyphae in chronic invasive, non caseating granulomas with dense fibrosis in granulomatous invasive, and infarction with suppuration in acute fulminant FRS. Aspergillus sp. was the commonest etiologic agent. To conclude, predisposing risk factors were more common in invasive FRS than in non-invasive sinusitis and Aspergillus species was the most common etiologic agent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fungal rhinosinusitis (FRS), hitherto considered uncommon, is being recognized and reported with increasing frequency since last two decades [1]. Clinically, it may be acute or chronic. Chronic FRS accounts for 6–12% of culture or histologically proven chronic sinusitis [2–5]. Based on histopathologic findings and invasion of mucosal layer, FRS is categorized into three non-invasive forms: allergic, chronic non-invasive (sinus mycetoma), and saprophytic colonization; and three invasive forms: chronic invasive, granulomatous invasive, and acute fulminant (necrotizing) [1, 6–8]. There is still controversy regarding the classification and the diagnostic criteria. The manifestations of the disease are dependent on the patient’s immunologic status. Acute invasive form occurs in immunocompromised patients and the course varies with the severity of immunocompromise. Chronic invasive form occurs in mildly immunocompromised patients and granulomatous invasive form occurs in immunocompetent individuals. Saprophytic fungal crusts occur in immunocompetent individuals. Allergic FRS occurs in patients with an allergy to the fungus [8, 9].

Certain geographic variations in the frequency of the histologic subtypes were reported [1, 10, 11]. Granulomatous invasive FRS was reported to be unique to countries with hot and dry climates like India, Pakistan, and Sudan, and Aspergillus flavus was isolated from all cases of granulomatous FRS. In India, FRS was reported to have a high incidence in North India [3, 12]. There were few reports of FRS from South India [10, 13, 14].

The etiological agents of FRS reported from India differ from those reported from western countries. Aspregillus sp. was commonly isolated from India and A. flavus was the most common isolate from granulomatous invasive forms [1, 3, 10]. Dematiaceous fungi were the common etiologic agents for allergic FRS in the western countries [11]. In India, a high prevalence of FRS was reported from North India, but very few reports were available from South India [1, 3, 10, 13, 14]. Diagnosis of various subtypes is important for management and prognosis and knowledge of etiological agent helps in directing appropriate antifungal therapy in certain subtypes [8]. In this paper, we report a series of 63 patients diagnosed on histology from South India.

Material and methods

Retrospective review of case records of histologically verified FRS from January 2005 to December 2008 was done. These included biopsies and debridement specimens from patients presented to our institute and also from patients referred from other hospitals. The data collected included demographic details, predisposing risk factors, clinical characteristics, extent of the lesion on imaging, endoscopic findings, and surgical details. Culture reports were collected wherever tissue was submitted for culture studies.

The biopsy sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS), periodic acid Schiff (PAS) stains. Masson Fontana (MF) stain was done when allergic mucin was seen on H&E stain. When culture confirmation was not available, the type of fungus was identified on morphological features. Slender septate hyphae with acute angle branching were diagnosed as septate mold. Broad aseptate hyphae with irregular branching were diagnosed as Zygomycetes sp., and Pseudohyphae with budding yeast forms were diagnosed as Candida sp.

The histological features were reviewed along with the type of fungus grown in the culture or identified by the morphological characteristics of fungus in the biopsy. The sinusitis was classified based on histological features according to the diagnostic criteria of de Shazo et al. [6, 7] into allergic, chronic non-invasive, chronic invasive, granulomatous invasive, and acute fulminant FRS.

Results

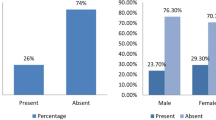

During the study period, 138 paranasal sinus mucosal resections were studied and FRS was the diagnosis in 63 patients. These included 45 males and 18 females with a mean age of 46 years (age range 19–84 years). Predisposing factors were identified in 19 patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) being the commonest. The other risk factors included one each of renal transplantation, autoimmune disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

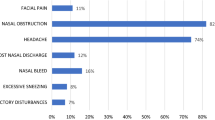

Histologically sinus infection in patients was classified as follows: (1) allergic in 15 (23.8%); (2) chronic non-invasive in 1 (1.6%); (3) chronic invasive in 10 (15.87%); (4) granulomatous invasive in 19 (30%); and (5) acute fulminant FRS in 18 (28.5%). Culture reports were available in 13 (20.63%) patients only. The clinical syndromes, predisposing factors, and the fungus species on culture in the five types of FRS were given in Table 1.

Allergic FRS (n = 15)

None of the 15 patients with allergic FRS had any predisposing factors. Nasal obstruction was the presenting feature in all the 15 patients with associated headache in four, nasal discharge in two and saddle nose in one. Clinically, all had rhinitis and four of them had associated allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. All patients had bilateral multiple nasal polyps. Imaging showed hyperdense to heterogenous soft tissue masses in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses in all the 15 patients.

Grossly, the polyps were mucoid, rubbery, and brownish to blackish in colour. Microscopically, there was characteristic laminated eosinophilic material with eosinophils and Charcot–Leyden crystals. The mucosa was edematous and there was no mucosal invasion. On GMS stain, fungal hyphae were slender and septate with acute angle branching (Fig. 1). On MF stain hyphae were positive for melanin in five biopsies. Culture was available in two samples only: one grew A. flavus and the other Aspergillus fumigatus.

Chronic non-invasive FRS (n = 1)

The patient with solitary maxillary fungal ball presented with nasal stuffiness. He had no predisposing factors. Imaging showed a mass lesion in the right maxillary antrum. Grossly, it was a brownish soft mass, and microscopically it was composed of tightly packed slender septate acute angle branching hyphae with few neutrophils. It was identified as septate mold probably Aspergillus sp. Culture was not available.

Chronic invasive FRS (n = 10)

The clinical syndromes included orbital apex syndrome in eight and cavernous sinus syndrome in two. Predisposing factors were identified in two patients and both had DM. Imaging showed mass lesion in the ethmoid sinus with invasion of the orbit, extending into orbital apex and/or cavernous sinus, and soft tissues. Histology showed sparse lymphomononuclear infiltrate with few foreign-body-type giant cells. GMS stain showed numerous fungal hyphae which were slender septate with acute angle branching, most probably Aspergillus sp. There was vascular invasion. Culture was not available in any sample.

Granulomatous invasive FRS (n = 19)

None of the 19 patients with granulomatous invasive FRS had any predisposing factors. The clinical syndromes included proptosis with limitation of eye movements in ten, cavernous sinus syndrome in six, and polyneuritis cranialis in three. Imaging showed multiple sinus involvement with orbital, cavernous sinus, or intracranial involvement with bone destruction. Maximal surgical excision was done in all the patients. Histology showed granulomatous inflammation with extensive fibrosis. The granulomas consisted of numerous foreign body giant cells, less number of epithelioid cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils. On GMS stains, there were slender septate hyphae and morphologically the fungi were septate molds probably Aspergillus sp. (Fig. 2). Material was submitted for culture in nine samples and all of them grew A. flavus.

Granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. a Giant cell rich granulomas with fibrosis and mixed inflammatory infiltrate (H&E; ×100). b Giant cell with intracytoplasmic negative staining fungal hyphae (H&E; ×400). c Narrow, septate, acute angle branching hyphae of Aspergillus sp. within the cytoplasm of giant cell (GMS; ×400)

Acute fulminant FRS (n = 18)

Predisposing factors were present in 17 of the 18 patients. Fourteen of these patients had DM. The clinical syndromes included rhino-orbital syndrome in eight, rhino-orbito-cerebral in eight, and rhino-cerebral in two. Imaging showed multiple sinus involvement with extension to orbit, intracranial compartment, and soft tissues. Extensive surgical debridement was done in all patients and radical resection was done in one patient.

Histologically, there was infarction and suppurative inflammation in all the patients with or without angio-invasion. Histologically on H&E and GMS stains, the fungal morphology was broad aseptate hyaline pale hyphae with irregular branching, consistent with Zygomycetes sp. in 15 samples (Fig. 3). In three samples, the fungal hyphae were slender septate hyphae with acute angle branching consistent with septate mold, most probably Aspergillus sp. Pseudohyphae and yeast forms of Candida sp. were seen in four biopsies in addition to Zygomycetes sp. Culture was available in two samples only, which was Rhizopus arrhizus.

Discussion

Fungal rhinosinusitis is considered to be an uncommon condition, particularly in South India. Our institute, primarily being one of the university hospitals in South India, and not routinely dealing with otolaryngological biopsies, deals with referral biopsies and neurosurgical samples for invasive sinonasal disease. So there is a bias in sample size with more number of invasive histologic subtypes, and minimum number of non-invasive subtypes. Hence this study does not reflect the prevalence of individual histologic subtypes in this part of the country. This is the reason for small number of samples for allergic and chronic non-invasive FRS. There were no biopsies diagnosed as saprophytic fungal infestation in this series as such individuals would often be asymptomatic [8, 15].

Allergic FRS is a distinct clinicopathologic entity in which there is a non-invasive pansinusitis that occurs in immunocompetent individuals with a strong history of atopy and elevated levels of total immunoglobulins (Ig) E and peripheral eosinophilia [11]. Allergic FRS is reported to have geographic variation in incidence and etiology. Allergic FRS was reported from both North India and South India and A. flavus was the most common etiologic agent in both regions followed by Aspergillus fumigatus [1, 3, 10, 14, 16]. In our series allergic FRS was seen in 15 patients and culture was available in two samples only which grew A. flavus in one and A. fumigatus in the other. In contrast to this, the etiological agents of allergic FRS in North America were dematiaceous fungi, such as Bipolaris sp., Curvularia sp., Alternaria and others [11, 17, 18]. Bent and Kuhn [19] defined the criteria for the diagnosis of allergic FRS. Nasal polyposis, characteristic CT scan findings and eosinophilic mucus were the accepted criteria.

However the most reliable indicator for the diagnosis of allergic FRS was histopathology and all our patients were diagnosed by the characteristic allergic mucin with scattered fungal hyphae. The fungal hyphae were delineated on GMS stain. Torres et al. [11] used MF stain to distinguish the pigmented dematiaceous fungi from other septate fungi. However, MF stain cannot be used to reliably differentiate dematiaceous fungi from other septate fungi [20]. Only 5 out of 15 of our biopsies were positive with MF stain. Cultures were not available in all our biopsies.

Knowledge of the fungal organism is important in directing appropriate antifungal therapy and possibly in selecting the correct antigens for postsurgical immunotherapy in allergic FRS [8]. Michael et al. [10] proposed that the prolonged exposure to environmental fungi due to occupation or housing pattern in India in contrast to the developed countries as contributing factors for the difference in the etiological agents for allergic FRS.

de Shazo et al. [6, 7] described diagnostic criteria for chronic invasive FRS and granulomatous invasive FRS. Both the forms were associated with prolonged clinical course, slow disease progression, sinusitis on radiology and evidence of hyphal forms within sinus mucosa, submucosa, blood vessel or bone [1, 6, 7, 21]. Chronic invasive FRS is characterized by orbital apex syndrome, dense accumulation of hyphae and clinically takes a chronic recurring course and seen in patients with DM. Distinction from granulomatous invasive FRS may not be clear clinically. Histopathology helps in distinguishing the two entities [1, 21]. Chronic invasive FRS shows invasion of mucosa with or without blood vessel invasion and an infiltrate of lymphocytes, plasma cells and few necrotizing granulomas. In contrast, granulomatous invasive FRS has a geographical incidence and occurs in India, Pakistan, Sudan and some parts of United States. It occurs in young immunocompetent individuals and histology shows granulomas with a few fungal hyphae belonging almost exclusively to A. flavus.

In our series, chronic invasive FRS was seen in ten patients and history of DM was present in only two. Similar observations were made earlier by Michael et al. [10] who proposed that malnutrition in Indian patients may be a contributing factor in such patients. The authors also proposed that patients may not be known diabetics at the time of diagnosis [10]. The abundance of fungal hyphae in chronic invasive FRS was thought to be due to progression of ethmoidal sinus mycetoma becoming invasive and extending to orbit [1].

All our patients with granulomatous invasive FRS were immunocompetent and on histology had dense fibrosis and few fungal hyphae Chakrabarthi et al. reported that A. flavus was the only and possibly exclusive etiologic agent in granulomatous invasive form [1]. Our results were similar. Both chronic invasive and granulomatous invasive should be treated with surgical debridement and systemic antifungal treatment to prevent recurrences [1, 21]. However, chronic invasive FRS should be treated as aggressively as acute fulminant FRS with radical surgery in view of the poor outcome [1].

Acute fulminant FRS is the most severe form and almost always occurs in immunosuppresed individuals. It is often fatal if untreated. There were 18 patients in this series and 17 of them had predisposing risk factors with DM being the commonest. The most frequent fungal isolate encountered in patients with acute fulminant FRS was R. arrhizus [10, 22, 23]. R. arrhizus belongs to the Zygomycetes group which is angioinvasive. This accounts for the destructive nature of the FRS and morbidity and mortality associated with this type of FRS [10]. Other than Zygomycetes sp., Aspergillus sp. also were reported as etiologic agents of acute fulminant form [1, 10]. In our series, though not culture proven, septate molds consistent with morphology of Aspergillus sp. were seen in 3/15 samples. Infarct type of necrosis with neutrophilic infiltration on histology in an immuno suppressed individual with sinusitis should raise the possibility of acute fulminant FRS and appropriate fungal stains should be performed to confirm the diagnosis, so that immediate treatment can be started.

The major limitation of the present study is the lack of culture confirmation for nearly 80% of cases. The diagnosis was based mainly on morphology. There are limitations of diagnosis based only on morphology and especially septate molds cannot be differentiated on morphologic basis alone from dematiaceous fungi. Antifungal susceptibility also varies with different species. But in absence of culture, pathology and morphology of the fungus on special stains provide important clues for diagnosis.

Conclusion

To conclude, FRS though uncommon, should be considered in the interpretation of all paranasal sinus biopsies or resections. Histology is very important in the diagnosis of subtypes of FRS. DM being very common in India, patients may present with undiagnosed DM and invasive sinus disease, which requires aggressive management. Awareness of histological features is important for proper subcategorization and appropriate treatment.

References

Chakrabarthi A, Das A, Panda WK (2004) Overview of fungal rhinosinusitis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 56:251–258

Chakrabarti A, Sharma SC, Chandler J (1992) Epidemiology and pathogenesis of paranasal sinus mycoses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 107:745–750

Panda NK, Sharma SC, Chakrabarti A, Mann SB (1998) Paranasal sinus mycoses in North India. Mycoses 41:281–286

Granville L, Chirala M, Cernoch P, Ostrowski M, Truong LD (2004) Fungal sinusitis: histologic spectrum and correlation with culture. Hum Pathol 35:474–481

Taxy JB (2006) Paranasal fungal sinusitis: contributions of histopathology to diagnosis: a report of 60 cases and literature review. Am J Surg Pathol 30:713–720

de Shazo RD, O’Brien N, Chapin K et al (1997) A new classification and diagnostic criteria for invasive fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123:1181–1188

de Shazo RD, Chapin K, Swain R (1997) Fungal sinusitis. N Engl J Med 337:254–259

Ferguson BJ (2000) Definitions of fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 33:441–449

Ence BK, Gourley DS, Jorgensen NL et al (1990) Allergic fungal sinusitis. Am J Rhinol 4:169–178

Michael RC, Michael JS, Ashbee RH, Mathews MS (2008) Mycological profile of fungal sinusitis: an audit of specimens over a 7-year period in a tertiary care hospital in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 51:493–496

Torres C, Ro JY, el-Naggar AK, Sim SJ, Weber RS, Ayala AG (1996) Allergic fungal sinusitis: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Hum Pathol 27:793–799

Chakrabarthi A, Sharma SC (2000) Paranasal sinus mycoses. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 42:293–304

Murthy JMK, Sundaram C, Prasad V, Purohit AK, Laxmi V (2001) Sinocranial aspergillosis: a form of central nervous system aspergillosis in South India. Mycoses 44:141–145

Rupa V, Jacob M, Mathews MS, Job A, Kurien M, Chandi SM (2002) Clinicopathological and mycological spectrum of allergic fungal sinusitis in South India. Mycoses 45:364–367

Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Kern EB et al (1999) The diagnosis and incidence of allergic fungal sinusitis. Mayo Clin Proc 74:877–884

Saravan K, Panda NK, Chakrabarti A et al (2006) Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: an attempt to resolve the diagnostic dilemma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 132:173–178

De Shazo RD, Swain RE (1995) Diagnostic criteria for allergic fungal sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 96:24–35

Manning SC, Shaefer SD, Close LG et al (1991) Culture-positive allergic fungal sinusitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117:174–178

Bent JP, Kuhn FA (1994) Diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 99:475–485

Kimura M, Mc Ginnis MR (1998) Fontana–Mason stained tissue from culture proven mycoses. Arch Pathol Lab Med 122:1107–1111

Stringer PS, Ryan MW (2000) Chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 33:375–387

Sundaram C, Mahadevan A, Laxmi V et al (2005) Cerebral zygomycosis. Mycoses 48:396–407

Sundaram C, Umabala P, Laxmi V et al (2006) Pathology of fungal infections of the central nervous system: 17 years’ experience from Southern India. Histopathology 49:396–405

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Challa, S., Uppin, S.G., Hanumanthu, S. et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis: a clinicopathological study from South India. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 267, 1239–1245 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1202-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-010-1202-6