Abstract

Since 1995 patients with T1a glottic carcinomas have been treated with laser surgery at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Rikshospitalet in Oslo. During this period we have in many cases noticed an inconsistency between the clinical outcome and the histopathological report describing that the resection margins were not free. We wanted to investigate this discrepancy, and the charts with the histopathological reports of 171 patients treated between 1995 and 2005 have been reviewed. Seventeen patients (10%) experienced a recurrence of the initial disease and were treated by repeated laser surgery, radiotherapy, or radiotherapy and laryngectomy. Two patients (1%) had died from the disease. In 36% of the cases (62 patients) the histopathological report indicated “not free” or “probably not free” resection margins. The discrepancy between the histopathological reports and the clinical outcome reflects the pathologist’s difficulty in orienting and determining resection margins in laser-resected specimens. Because of the low number of recurrences or metastases, the verdict of a violated resection margin should probably not be crucial for further treatment. The surgeon’s peroperative judgement may be trusted, however, with very close follow-up in order to detect early recurrences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Until 1995 regardless of stage, radiotherapy was the preferred treatment of laryngeal carcinoma in Norway, as in most European countries. At this point several German studies indicated that the results of laser surgery of small glottic carcinomas were equal to or better than radiotherapy with respect to residual and recurrent disease [1–3]. The advantages of surgical treatment such as shorter treatment time, less side effects and low cost were further advocated. Against this background our department has changed its treatment protocol of laryngeal cancer and since 1995 all T1a glottic carcinomas have been treated with laser resection.

Since the start of the new treatment regime, we have experienced an inconsistency between our clinical impression of a radical removal of the tumour and the histopathological report where resection margins were often described as “not free”. However, only in a few cases we advised further treatment, but rather trusted the clinical peroperative judgement and that a possible recurrence would be discovered at a close follow-up regimen.

In this retrospective study we have reviewed the patient records with the histopathological reports to see whether this strategy has been valid or not.

Materials and methods

Between 1995 and 2005, 171 patients (153 males, 18 females) with a T1a glottic carcinoma have been treated with laser surgery. The mean age was 67 years (range 38–90 years). The mean observation time was 51 months (range 1–120 months). The majority of the patients had been referred from another ENT institution or from an ENT specialist. In most cases the histological diagnosis had been previously established by biopsy. Some of the patients were referred with a clinical picture of malignancy of the glottic cord without previous verification of biopsy. Before surgery the patients were evaluated with a flexible laryngoscopy focusing on the extent of the disease in particular on subglottic growth and infiltration via the anterior commisure to the opposite cord or to the ventricle, as we had strictly confined the surgical treatment to T1a glottic carcinomas. In the majority of cases and always when the anterior commisure was involved, a CT scan was part of the preoperative work-up.

The surgical procedure was carried out under general anaesthesia with jet-ventilation. Before starting surgery a final examination was done with rigid endoscope to determine the stage and operability. We have used the Sharplan 1030 laser attached to the Leica M 500-N microscope with the Unimax 2000 micromanipulator giving a spot size of less than 0.3 mm. The typical settings were regular pulse, continuous mode and strength of 1 W. Bulky tumours affecting more than half of the vocal cord or that extended into the laryngeal ventricle were usually divided with a perpendicular incision and removed in two pieces. In some cases a part of the ventricular fold also had to be removed to get sufficient exposure. The tumour specimens were mounted on a piece of cork or cardboard and marked with pins, fixated in 4% formaldehyde and then sent to the pathology clinic for histological examination. The formaldehyde-fixed specimens were entirely embedded in paraffin after thorough orientation as described by the surgeon in order to be able to assess the resection margins. Sections (4 μm) were mounted on glass slides and stained with a modified HE staining. Stained sections were histologically evaluated by one or more experienced pathologists. The histopathological reports included confirmation of a superficial carcinoma and/or carcinoma in situ, and an evaluation of the resection margins relating to carcinoma as well as squamous epithelial dysplasia. Difficulties in evaluating the resection margins by means of artefacts caused by the laser or tangentially cuts were usually described as either “uncertain”, “probably free” or “probably not free”.

The patients were usually discharged on the day of surgery. The postoperative follow-up was rigorous with videostroboscopy usually with the flexible endoscope every 6 to 12 weeks during the first year. After 1 year the patients were discharged from us and further follow-up was performed by the referring institution or the nearest ENT specialist.

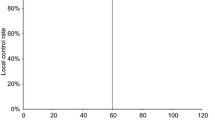

When this study was initiated the patient records, including the histopathological reports were reviewed retrospectively. The data were stored and analysed by means of SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A Kaplan–Meyer plot was used to illustrate the disease-free period. A case was censored when death had resulted from causes other than the original tumour or when there was no evidence of recurrence at the last follow-up consultation.

The pathology reports were classified according to the degree to which the resection margins were considered free or not.

Results

One hundred and fifty-four (90%) of the 171 patients were free of disease at the time of the study (Fig. 1). Fifteen patients had died of other reasons. Sixteen patients (9.4%) had developed a local recurrence and one patient metastatic disease regionally and died due to this condition. The total recurrence rate was accordingly 9.9%. Ten of the patients developed recurrence within 1 year following surgery. In three patients local recurrence did not develop until 3 years after treatment. Four of the patients with local recurrence had a second laser surgical procedure and have since remained free of disease. Twelve patients received radiotherapy (70 Gy over 7 weeks) and nine of these were cured. Two patients had a recurrence after radiation and underwent a total laryngectomy. One of these patients remained free of disease, while the other died due to stomal recurrence. For the material as a whole death due to laryngeal cancer was 1.2% and laryngeal preservation rate 99%.

Table 1 presents the review of the histology reports.

Discussion

When treating T1a glottic carcinomas with laser surgery, it is necessary to keep the resection margins as small as possible in order to obtain a good functional result. This is possible due to the special growth pattern of these tumours usually being exophytic, well defined and not invading the vocal ligament.

During the endoscopic operation it is imperative to have an optimal exposure, especially of the anterior commisure and the subglottic area. The contour of the vocal fold is usually followed from the laryngeal ventricle medially to the subglottic area and to reduce the heating of the tissue and thus the subsequent scarring of the vocal cord, the laser beam is preferably moved like a painting brush. The surgeon should at all times be aware of the importance of keeping the resection margins at least 1– 2 mm. Laser carbonisation of the squamous cell carcinoma differs from the normal mucosa and submucosa of the vocal cord and this feature makes it easier to recognise the outline of the tumour. An extensive tumour may have to be divided to have a complete exposure and in doing so one can easily see the borderline between neoplastic tissue and normal submucosa. The deep plane of excision, being the most difficult part of the operation especially if it is uncertain whether the vocal ligament is affected or not, may then be adjusted according to the in-depth infiltration. Before laser resection of the smallest T1a glottic carcinomas, we in some cases inject saline submucosally. This enables to find the plane between neoplastic tissue and the underlying vocal ligament. It further helps us to determine the in-depth invasion and reduces the thermal damage to the tissue.

Table 1 shows that in 15 cases there was no tumour tissue found in the operative specimen, although a biopsy taken preoperatively was conclusive of a malignant disease. The biopsy had consequently been curative without this being intentional. One of these patients, however, developed recurrent disease. We now recommend that a malignant appearing unilateral vocal cord lesion be treated as a T1a glottic carcinoma without taking a previous biopsy in advance. The patient will then have one, instead of two, surgical interventions in general anaesthesia. Moreover, a biopsy will never be fully representative of the lesion and an area of infiltration may be overlooked [4, 5]. A blind, deep biopsy may also be more harmful to the voice quality than a careful laser stripping of the pathological mucosa keeping the relationship to the vocal ligament at all times under control.

In our material there is a discrepancy between the pathology reports with a high percentage of unclear resection margins and low incidence of recurrences. In 62 patients the resection margins were either violated or showed tumour-suspect areas in the laser carbonised zone with thermic artefacts in order not to allow an exact conclusion. In this group nine tumours recurred. In 49 cases there was either no tumour in the resection margin or there were burns and artefacts in the margin not allowing an exact conclusion, but with a low probability of tumour in the resection margins. Two of these patients (4%) got a recurrence during follow-up. Twenty-four patients were described with uncertain margins where it was not possible to determine either free or violated margins on histological preparations. Three patients had recurrent disease. Looking into the 17 cases of recurrent disease (Table 1), there is a fair correlation between the pathology report and the clinical situation; however, only in 9 of 17 cases the margins were described as violated. The poor consistency between the pathology report and the clinical outcome is in part due to the difficulties in handling the specimens. It is often difficult for the surgeon to orient, mount and mark the generally small specimen, especially if the tumour had to be divided. The pathologist also has to take into account the shrinking of the specimen [6] as well as the fact that the laser leaves a carbonisation zone of 0.3 mm in the tissue which should be implemented in the specimen when assessing the resection margins.

Normally, the verdict of a violated resection margin would indicate further treatment which for this group of patients means either another laser surgical procedure or postoperative radiotherapy. The consequences for the patient would regardless of choice in many ways be negative. A second surgical procedure will mean a further loss of tissue, leave the vocal cord more scarred and result in a poorer voice quality. Radiotherapy will take 6–8 weeks and will have side effects lasting at least up to a year [7]. The patient will further be deprived of the possibility of another malignancy in the head and neck area being treated later [8] in addition to the added costs of radiotherapy for the society [9, 10].

We have disregarded the inconsistency between the clinical impression and the histopathological findings and rely on a close follow-up procedure and thus apply a “wait and see” attitude. The surgeon will have the sole responsibility for the treatment, from preoperative examination, through surgery and to the postoperative controls which will be scheduled every 6–8 weeks during the first year. To achieve good results several things have to be considered: Optimal equipment including both diagnostic tools and surgical instruments is essential. The CO2 laser must have all options and be attached to a micromanipulator which gives a spot size of 0.3 mm or less. The surgical skills including intimate familiarity with the anatomy of the vocal cord are extremely important and can only be learned by long-term training. Finally, the diagnostic precision is crucial including selecting patients for this type of surgery and for follow-up postoperatively in order to diagnose a recurrent disease as early as possible. The videostroboscopic examination should be carried out with the flexible laryngoscope to get an optimal view of the anterior commisure and the subglottic area. During the follow-up, comparisons with earlier recordings will be of utmost value to detect recurrent disease as early as possible.

Our results with a recurrence rate of only 10% compare favourably with other centres, with reported recurrence rates ranging from 6 to 18% [1–3, 6, 11, 12]. Moreover, in an earlier study we have showed that the quality of the voice after surgery was generally good and did not have a negative effect on the daily life of the patient [13]. However, in order to keep the standard at this level it is important that the surgeon has the skill and training as needed and gets the necessary volume of patients. In Norway with its 4.5 million inhabitants, we see approximately 30 new cases of T1a glottic carcinomas annually. These patients should, in our opinion, be centralised to no more than two centres where the most experienced laser surgeons should perform this kind of surgery.

References

Rudert H (1995) Technique and results of transoral laser surgery for small vocal cord carcinomas. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 49:222–226

Steiner W (1993) Results of laser microsurgery of laryngeal carcinomas. Am J Otolaryngol 14:116–121

Eckel HE, Thumfart WF (1992) Laser surgery for the treatment of larynx carcinomas: indications, techniques and preliminary results. Ann Otol Laryngol 101:113–118

Damm M, Sittel C, Streppel M, Eckel HE (2000) Transoral CO2 laser for surgical management of glottic carcinoma in situ. Laryngoscope 110:1215–1221

Gallo A, de Vincentis M, Mancicco V et al (2004) CO2 laser cordectomy for early stage glottic carcinoma: a long-term follow up of 156 cases. Laryngoscope 112:370–374

Remacle M, Lawson G, Jamart J, Minet M (1997) CO2 laser in the diagnosis and treatment of early cancer of the vocal cord. Eur Arch Otoorhinolaryngol 254:169–176

Boysen M, Løvdal O, Tausjø J, Winther FØ (1992) The value of follow-up in patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Eur J Cancer 28:426–430

Nordgren M, Abendstein H, Jannert M et al (2003) Health- related quality of life five years after diagnosis of laryngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 56:1333–1343

Cragle SP, Brandenburg RL (1993) Laser cordectomy or radiotherapy: cure rates, communication and cost. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 108:648–654

Myers EN, Wagner RL, Johnson JT (1994) Microlaryngoscopic surgery for T 1 glottic lesions: a cost- effective option. Ann Otol Laryngol 103:28–30

Eckel HE (2001) Local recurrences following transoral laser surgery for early glottic carcinoma: frequency, management and outcome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110:7–15

Peretti G, Piazza C Bolzoni A et al (2004) Analysis of recurrences in 322 TIS, T1 or T2 glottic carcinoms treated by carbon dioxide laser. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 113:853–858

Brøndbo K, Benninger M (2004) Laser surgery of T1a glottic carcinomas. Results and postoperative voice quality. Acta Otolaryngol 124:976–979

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brøndbo, K., Fridrich, K. & Boysen, M. Laser surgery of T1a glottic carcinomas; significance of resection margins. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 264, 627–630 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0233-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0233-5