Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of genital tract tuberculosis (TB) among infertile women during laparoscopic evaluation for infertility in a prospective observational study.

Methods

A total of 420 infertile women were included. All patients had laparoscopy and all suspicious lesions were biopsied and peritoneal fluids aspirated. Full endometrial curettage followed by histopathological examination was done for specimens. Polymerase chain reaction test (PCR) was performed for all peritoneal fluid samples and tissue biopsy.

Results

Genital tract tuberculosis was diagnosed with laparoscopy and confirmed by tissue biopsy in 24 patients (5.7%). Visual laparoscopic findings and direct tissue biopsy had the highest sensitivity and specificity (92–94%, respectively) followed by PCR (83–85%) and lastly endometrial biopsy (75–80%) for diagnosis of genital tuberculosis. The incidence of genital tuberculosis was higher among rural patients with low socioeconomic and educational levels.

Conclusion

Genital tuberculosis has a role in the etio-pathogenesis of infertility. Laparoscopy and direct tissue biopsy are the gold standards for its diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tuberculosis remains a major health problem in many developing countries and genital tuberculosis is still responsible for a significant proportion of female infertility. The World Health Organization in 1996 [1] reported that eight million new cases of tuberculosis are diagnosed annually. Genital tuberculosis has been steadily declining in developed countries [2]. While 5–10% of infertile females all over the world have genital tuberculosis, the incidence varies from less than 1% in the USA to nearly 13% in India [3].

Classically, genital tuberculosis has been described as a disease of young women, with 80–90% of patients being first diagnosed between the ages 20 and 40 years [4]. Primary genital tuberculosis is extremely rare and genital tract infection is almost always secondary to tuberculosis elsewhere in the body. The fallopian tube constitutes the initial focus of genital tuberculosis in 90–100% of patients, followed by the uterus (50–60%), the ovaries (20–30%), the cervix (5–15%) and lastly the vagina in 1% of patients [3]. Genital tract tuberculosis is an extremely indolent infection and the disease may not become manifest for more than 10 years after e initial seeding in the genital tract. The chief presenting complaints of young women are infertility, vaginal bleeding and chronic lower abdominal or pelvic pain [3]. Genital tuberculosis should always be considered in young patients presenting with unexplained infertility or repeated IVF failure [5].

A risk of genital tract tuberculosis should be considered for individuals with a past history of extra genital tuberculosis, chest X-ray with evidence of healed pulmonary tuberculosis and tuberculin test that yields a positive finding. Hysterosalpingography may show characteristic changes suggestive of tuberculosis infection including beading, sacculation, sinus formation and a rigid “pipestem” pattern of the fallopian tubes [6, 7]. Diagnosis is confirmed by histological examination that reveals typical granuloma or by acid-fast stain and culture of biopsies obtained by laparoscopy or endometrial curettage [8]. There have been reports about using mycobacterial purified protein antigens in enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assays (ELISAs) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to be of value in diagnosing tuberculosis [9, 10]. The aim of this study is to estimate the prevalence of genital tract tuberculosis among infertile women in a tertiary referral university hospital and to show the best way for diagnosis.

Materials and methods

The study comprised 420 infertile women among those attending the outpatient infertility clinic in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mansoura University Hospitals, Egypt, during the period January 2003 to September 2007 and all were admitted to have laparoscopy as a part of their infertility workup. All patients showed delayed conception for at least 1 year despite continuous marital relationship. All women had mid-luteal serum progesterone assay for documenting ovulation, hysterosalpingography for checking the uterus and tubes and semen analysis for their partners. The study was approved by the local hospital ethical committee and all patients gave formal consent before being included in the study. Laparoscopy was done using standard three-puncture technique. All procedures were performed by trained senior registrars or consultants. All abnormal findings suspicious for pelvic tuberculosis such as pallor of tissues, retort-shaped tubes, salpingitis isthmica nodosa at the proximal part of the tube, eversion of fimbrial end of the tube, distal tubal obstruction and scattered caseating material on pelvic peritoneum or genital organs were biopsied, when technically possible using scissors, and sent for histopathologic examination. Peritoneal fluids were aspirated and the washing of the pelvic peritoneum was done using 300 ml of Ringer lactated solution followed by aspiration. All correctable adhesions around the ovaries and tubes were treated using scissors and monopolar cutting current. Tubal patency was checked by transcervical injection of 50 ml of sterile methylene blue solution and by observing the passage through the fimbrial ends of the tubes. By the end of the procedure, the pelvis was irrigated with 1–1.5 l of lactated Ringer solution. During the same setting, endometrial sampling from all parts of the uterine cavity was done and all samples were sent for cytologic and histopathologic examinations.

All tissue and fluid samples were subjected separately to PCR examination for detection of specific DNA genomic sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. (The size of amplification product obtained is 123 bp by Hispano Lab. Carretra N-1, km 16, 200-28100 Alcobenraf, Madrid, Spain).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Odds ratio was used for strength of association between positive tissue biopsy and other diagnostic tools. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was blotted for studying sensitivity and specificity of different diagnostic parameters for the diagnosis of TB.

Results

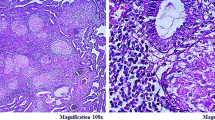

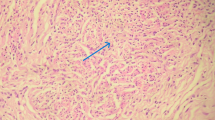

The study comprised 420 infertile women in total. Table 1 presents the patient characteristics. Most of the patients were aged between 30 and 34 years (40.9%), uneducated (47.6%), rural (57.1%) and housewives (62.4%). The overall incidence of genital tract tuberculosis among the infertile population was 5.7% (24 cases). Most of the patients were housewives, residing in rural areas (16/24). In Table 2 showing the clinical presentation of the tuberculosis patients, only one of three patients had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis. During laparoscopy, ten patients showed beading on the surface of the tubes, seven patients showed sacculation and one patient had a rigid “pipestem” pattern of the fallopian tubes. Most of the lesions (18 patients) were demonstrated on the fallopian tubes followed by ovaries (7 patients) and peritoneal surface (6 patients). Considering tissue diagnosis as the gold standard, Table 3 showing the different modalities used for the diagnosis of genital tuberculosis indicates that the most accurate diagnosis can be obtained by laparoscopy followed by PCR and endometrial biopsy. Visual diagnosis of tuberculosis (22 patients) during laparoscopy proved to be correct in all patients but one, which was proved by tissue diagnosis to be due to bilharziasis that was excluded from the analysis. Figure 1, which shows the ROC demonstrating sensitivity and specificity of the different diagnostic modalities for the diagnosis of tuberculosis indicates that laparoscopy had the highest sensitivity and specificity (92–94%), followed by PCR (83–85%) and endometrial biopsy (75–80%) (Figs. 2, 3).

Discussion

Tuberculosis is still a major infectious disease in many developing countries. Around 5–10% of infertile females all over the world have genital tuberculosis. In this study, the incidence of genital tract tuberculosis was 5.7% and was higher in rural housewives of low socioeconomic levels. The average age of the patients with genital tract tuberculosis ranged from 20 to 40 years. Schaefer et al. [4] and Jones et al. [3] found that female genital tuberculosis is a disease of young women and 80–90% of patients are first diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Sutherland [11], in a series of 204 genital tuberculosis patients encountered in the period 1951–1980, found that the average age at diagnosis was between 25 and 38 years. This study reported a high incidence of genital infection among infertile women in rural areas, especially in housewives whose economic development and public health conditions were poor. In Egypt, women’s educational levels are, sometimes, very low and some women have no knowledge about health care. In these communities, few clinics have simple and crude medical equipments, which result in increasing the chances of tuberculosis infection [3, 12].

Diagnosis of genital tuberculosis was best accomplished by laparoscopy and direct tissue biopsy followed by PCR and finally by endometrial biopsy. Negative endometrial biopsy does not rule out pelvic involvement with tuberculosis, since sampling errors are common and there may be tuberculous lesions in other genital parts without an associated tuberculosis endometritis. Therefore, laparoscopic assessment and biopsy from suspicious areas of internal organs (tubes, ovaries and peritoneum) showed high incidence of tuberculosis of the genital tract than endometrial biopsy. Fulk et al. [13] reported positive endometrial tissue in only 50% of the cases of genital tract tuberculosis. Laparoscopic evaluation of infertile women to rule out or to establish diagnosis of tuberculosis of genital tract seemed very essential. However, the gold standard for diagnosis of genital tract tuberculosis is still vindicating characteristic caseating granulomas in tissue biopsies. Bhanu et al. [14] showed that multiple sampling from different suspicious sites during laparoscopy and amplification of the mpt64 gene segment by PCR offered increased sensitivity in determining tuberculous etiology in female infertility. Jindal [15] reported that a definitive bacteriological diagnosis was generally difficult to achieve in genital tuberculosis before administration of anti-tuberculosis treatment. A high index of suspicion and several other morphological and/or laboratory criteria were employed. It is suggested that a stepwise algorithm can help in the management of these cases Although PCR is a technique that can be used to amplify extremely small amounts of a specific DNA genomic sequence; it does not distinguish live from killed organisms. So, patients receiving therapy may remain PCR positive for a time despite mycobacterial sterilization. It may be used to support clinical and histological diagnosis of atypical case with negative culture [8, 9, 14, 15]. Its sensitivity can be increased when it is employed after laparoscopic selection of tuberculosis suspicious cases.

The treatment options for genital tuberculosis consist of initial multidrug medical therapy for a period of 6 months to 1 year. Pregnancy after a diagnosis of genital tuberculosis is rare and when it does occur, it is more likely to be ectopic or result in spontaneous abortion. In 1976, Schaefer [4] reviewed 7,000 cases of genital tuberculosis from the literature and stated that 155 patients had full-term pregnancies (2.2%), 67 had abortions (0.9%), and 125 (1.8%) had ectopic pregnancies. When the histologic examinations were used as testimony of genital tuberculosis, the number of full-term pregnancies was even reduced. Tripathy [16] reported a conception rate of 19.2%, while the live birth rate was only 7.2%. Tuboplastic macro- or micro-surgical operations in these cases very rarely lead to term pregnancies. They even increase the chances of tubal pregnancy and may reactivate silent pelvic tuberculosis. Therefore, they are contraindicated [17, 18]. IVF represents a useful treatment and improves the chances of fertility in what was earlier considered a desperate situation. Soussis et al. [19] reported 28.6% success rate with IVF in 13 patients with histologically proven genital tuberculosis. Frydman et al. [20] reported 25% pregnancy rate per transfer in tuberculous infertility. Thus, IVF represents the only treatment for tubal and possibly endometrial tubercular infertility.

Genital tuberculosis still has a role in the etiopathogenesis of infertility in the Egyptian community. The incidence of genital tract tuberculosis among infertile women is escalating and amplified among rural, low socioeconomic and low educational level patients. Laparoscopy is essential for the diagnosis of genital tract tuberculosis, and negative endometrial biopsy does not rule out the pathology. It can be argued that a widespread population vaccination program will help to decrease the number of women with infertility caused by genital tuberculosis.

Change history

21 June 2022

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06668-0

References

Global Tuberculosis Program (1998) In: Global tuberculosis control. World Health Organization 237, WHO report, Geneva

Jahromi BN, Parsanezhad S, Shilazi RG (2001) Female genital tuberculosis and infertility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 75:269–272. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00494-5

Jones HW, Went AC, Burnett LS (1988) Novak’s textbook of gynecology. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, pp 557–569

Schaefer G (1976) Female genital tuberculosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 10:232–237

Dam P, Shirazee HH, Goswami SK (2006) Role of latent genital tuberculosis in repeated IVF failure in the Indian clinical setting. Gynecol Obstet Invest 61:223–227. doi:10.1159/000091498

Anthony FJ (2000) Identification and management of tuberculosis. Am Fam Physician 60:2667–2681

Raut VS, Mahashur AA, Sheth SS (2001) The Mantoux test in the diagnosis of genital tuberculosis in women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 72:165–169. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(00)00328-3

Quershi RN, Samad S, Hamid R, Laka SE (2001) Female genital tuberculosis revisited. J Pak Med Assoc 51(1):16–18

Moussa OM, Eraky I, El-Far MA, Osaman HG, Ghoneim MA (2000) Rapid diagnosis of genitourinary tuberculosis by polymerase chain reaction and nonradioactive DNA hybridization. J Urol 164(2):584–588. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67427-7

Honore BS, Vincensini JP, Giacuzzo V, Lagrange PH, Herrmann JL (2003) Rapid diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by PCR: impact of sample preparation and DNA extraction. J Clin Microbiol 41(6):2333–2339

Sutherland AM (1983) The changing pattern of tuberculosis of the female genital tract: a thirty-year survey. Arch Gynecol 234:95–101. doi:10.1007/BF00207681

Varma T (1991) Genital tuberculosis and subsequent fertility. Int J Gynec Obstet 35:1–11

Falk V, Ludviksson K, Agreen G (1980) Genital tuberculosis in women: analysis of 187 newly diagnosed cases from 47 Swedish hospitals during the ten-year period 1968 to 1977. Am J Obstet Gynecol 138:933–944

Bhanu NV, Singh UB, Chakraborty M, Suresh N, Arora J et al (2006) Improved diagnostic value of PCR in the diagnosis of female genital tuberculosis leading to infertility. J Med Microbiol 54(10):927–931. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.45943-0

Jindal UN (2006) An algorithmic approach to female genital tuberculosis causing infertility. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 10(9):1045–1050

Tripathy SN, Tripathy SN (2002) Infertility and pregnancy outcome in female genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 76:159–163. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00525-2

Frantzen C, Schlosser HW (1982) Microsurgery and postinfectious tubal infertility. Fertil Steril 38:397–420

Ballon SC, Clewell WH, Lamb EJ (1975) Reactivation of silent pelvic tuberculosis by reconstructive tubal surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 122:991

Soussis I, Trew G, Matalliotakis I (1998) In vitro fertilization treatment in genital tuberculosis. J Assist Reprod Genet 15:378–380. doi:10.1023/A:1022533016670

Frydman R, Eibschitz I, Belaisch-Allart JC (1985) In vitro fertilization in tuberculous infertility. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf 2:184–189. doi:10.1007/BF01201795

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Nezar, M., Goda, H., El-Negery, M. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Genital tract tuberculosis among infertile women: an old problem revisited. Arch Gynecol Obstet 280, 787–791 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-009-1000-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-009-1000-9