Abstract

Background

Fear of death (FoD) is an exceptionally stressful symptom of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), which received little scientific attention in recent years. We aimed to describe the prevalence and factors contributing to FoD among STEMI patients and assess the impact of FoD on prehospital delay.

Methods

This investigation was based on 592 STEMI patients who participated in the Munich Examination of Delay in Patients Experiencing Acute Myocardial Infarction (MEDEA) study. Data on sociodemographic, clinical and psycho-behavioral characteristics were collected at bedside. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with FoD.

Results

A total of 15 % of STEMI patients reported FoD (n = 88), no significant gender difference was found. STEMI pain strength [OR = 2.3 (1.4–3.9)], STEMI symptom severity [OR = 3.7 (2–6.8)], risk perception pre-STEMI [OR = 1.9 (1.2–3.2)] and negative affectivity [OR = 1.9 (1.2–3.1)] were independently associated with FoD. The median delay for those who experienced FoD was 139 min compared to 218 min for those who did not (p = 0.005). Male patients with FoD were significantly more likely to delay less than 120 min [OR = 2.11(1.25–3.57); p = 0.005], whereas in women, this association was not significant. Additionally, a clear dose–response relationship between fear severity and delay was observed. Male FoD patients significantly more often used emergency services to reach the hospital (p = 0.003).

Conclusions

FoD is experienced by a clinically meaningful minority of vulnerable STEMI patients and is strongly associated with shorter delay times in men but not in women. Patients’ uses of emergency services play an important role in reducing the delay in male FoD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the acute phase of a ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), patients usually experience a variety of complaints, most commonly chest pain and shortness of breath. However, given the life-threatening nature of an STEMI [1, 2], it is not surprising that it may evoke varying degrees of fear, ranging from mild fear and distress up to fear of death (FoD) [3–5]. FoD is defined as “a multi-dimensional construct related to fear of and anxiety related to the anticipation and awareness of the reality of dying and death”, which is one of the most distressing and frightening events that one can ever experience [6].

Traditionally, FoD has been described in many cardiology textbooks as an extremely stressful and, therefore, immobilizing symptom of STEMI [5]. During the acute phase of STEMI, all patients’ lives are under severe threat, yet the frequency of FoD reported in previous studies varies notably; this could be partly explained by the heterogeneity of patients (AMI, angina and even non-ischemic chest pain), the limited number of included patients as well as the considerable time gap between acute event and patients’ evaluation [7–9]. Furthermore, this also raises the question whether the risk of FoD during STEMI is promoted by the objective severity of the disease or by the perceived severity of the event or even by a subset of patients’ background characteristics.

Previous studies have provided inconsistent findings with respect to the impact of FoD on the prehospital delay of patients during AMI [3, 7–10]. We hypothesized that FoD would be associated with protracted PHD, based on the assumption that FoD is an extremely stressful event that may impede patients’ decision-making ability [6], leading to performance paralysis according to the Yerkes–Dodson (inverted-U) model [11], which dictates that performance increases with stimuli (ex. fear), but only up to a point when performance then deteriorates by increasing stimuli. Despite the presumable impact of FoD on delay times, FoD has received little attention in international guidelines and recent literature addressing the issue of prehospital delay in STEMI patients [12].

Therefore, the main aims of this study were threefold: (1) to assess the prevalence of FoD among a homogenous sample of STEMI patients, (2) to determine the sociodemographic, clinical, behavioral and psychological factors contributing to FoD and (3) to assess the impact of FoD on PHD.

Methods

The multicenter, cross-sectional MEDEA study (Munich Examination of Delay in Patients Experiencing Acute Myocardial Infarction) was conceived with the aim to document the prehospital delay of patients with STEMI, and the factors which may contribute to prolonged delay.

Study design

Patients were recruited from the following university or municipal hospitals with a coronary care unit, belonging to the Munich emergency system network clinics: Klinikum-Augustinum, Klinikum-Bogenhausen, Deutsche Herz Zentrum München, Klinikum-Harlaching, Universitäts-Klinikum der LMU Innenstadt, Klinikum-Neuperlach, Universitäts-Klinikum Rechts der Isar der TUM and Klinikum-Schwabing. The MEDEA study was approved by the Ethic Commission of the Faculty of Medicine of the Technischen Universität München (TUM) on 10.12.2007. The main inclusion criterion was diagnosis of STEMI, as evidenced by typical clinical symptoms and the observation of prolonged ST elevations, as measured via ECG. In addition, the diagnosis was supported by laboratory evidence of elevated myocardial biomarker levels [12]. Patients were excluded from the study if they had to be resuscitated, if STEMI occurred whilst already hospitalized and if they were unable to answer the questionnaires properly due to language barriers or cognitive impairment. There were no age restrictions.

Standardized operation procedures (SOPs) were implemented to ensure the consecutive referral of eligible patients into the study. To this end, physicians in each collaborating hospital supervised the MEDEA entry criteria and were contacted by MEDEA personnel twice a week. Patients were interviewed in the hospital immediately after referral from intensive care. All patients were informed of the aim and procedures of the study and also that taking part in the study would have no effect on their treatment. All patients were required to sign a declaration of consent. The physician on location informed the patient and consent to participate to avoid unnecessary patient contact by the MEDEA team. All data acquisition was then performed by the MEDEA research team.

Sample

From 12.12.2007 until 31.05.2012, data on 619 patients who were capable of taking part in the study were collected. There were few dropouts in the study since physicians did not inform MEDEA of STEMI patients who were unable to answer the study questionnaire due to their critical condition (e.g., coma). Approximately 18 % of patients were excluded: 4 % due to not meeting inclusion criteria and 14 % due to absence of consent or missing data.

In the present analysis, twenty-seven patients with missing values on FoD were excluded. Comparison of included and excluded patients showed no significant differences in age, sex, sociodemographic, clinical, psychological and other relevant covariates.

Data collection

The data collection process was divided into three sections. First, a bedside interview was conducted with trained MEDEA personnel. Second, a self-administered questionnaire was handed to the patients, which was filled by the patient without supervision. Third, data were collected from the hospitals’ patient charts.

Measures

Fear of death (FoD)

FoD was measured using one binary coded item: “During this situation, did you experience fear of death”. Additionally, fear severity was assessed in a separate module using one Likert-scaled item ranging from 0(least severe) to 10(most severe). Participants were categorized into 3 groups: mild fear (0–3), moderate fear (4–7) and severe fear (8–10).

Prehospital delay (PHD)

Patients were asked to recall at what time acute symptoms began. The time difference between symptom onset and first ECG in the clinic constitutes “prehospital delay” (PHD), measured in minutes. PHD was thus available as a continuous variable which was heavily left-skewed. PHD did not approximate a normal distribution after transformations and, therefore, was further dichotomized into 2 groups: <120, and ≥120 min.

Baseline and clinical measures

The hospital patient charts and bedside patient interviews provided data on risk factors, presenting symptoms, important clinical measures as well as possible complications. Prodromal symptoms were defined by the presence of any of the symptoms related to coronary artery disease. The variable “cardiologist visits” describes whether patients had visited a cardiologist up to 6 months prior to the indexed STEMI event.

Patient behavioral responses to STEMI

A German version of the Response to Symptoms Questionnaire was used to measure the behavior and subsequent reaction of both the patient as well as witnesses [13]. The cardiac denial of illness was also measured using an eight-item scale [14]. The structured bedside interview included a documentation of pain intensity, risk perception, symptom expectation and symptom severity.

Psychological measures

The German version of Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7), WHO-5 wellbeing index, Major Depression Inventory (MDI) scale and Type-D scale (DS14) were used. A GAD-7 score above or equal to 10 indicates anxious participants [15], a WHO-5 score below or equal to 50 indicates suboptimal wellbeing [16], a DS14 score above or equal to 10 indicates negative affective trait [17]. According to the DSM-IV definition, patients who have at least five symptoms in the MDI scale, of which at least one must be a ‘core’ symptom, are diagnosed with major depression [18].

Data analysis

Differences between dichotomous variables were assessed using the Chi-square test. When comparing ordinal variables with more than two outcomes, the Mantel–Haenszel Chi-square test was used. Differences in age were assessed using the t test. The nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used for assessing differences in median prehospital delay times. Age- and sex-specific analyses and multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess factors associated with FoD. All factors that were significant in the bivariate analysis were included as potential confounders in the multivariate logistic regression model. Twenty patients were excluded from the multivariate analysis due to missing values in covariates. No significant differences were found.

The impact of FoD on PHD (delay time <120 vs. ≥120 min) was also assessed by logistic regression model using stepwise variable selection technique (stay criterion p < 0.05) and stratifying by gender. All statistical analyses were run in SAS (Version 9.2, SAS-Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The significance level α was set at 0.05. The analysis and the description in this paper follow the STROBE guidelines for cross-sectional studies [19].

Results

The present investigation included a total of 592 patients, with 158 women (26.7 %) and 434 men (73.3 %). Mean age was 62.5 ± 12.15 years; men were on average 8 years younger than women (p < 0.001). In the total sample, median delay was 200(100–684) minutes (IQR = 584).

Prevalence of fear of death and background trait characteristics

During the acute phase of STEMI, 88(14.9 %) patients experienced FoD. FoD was reported with comparable frequency in men and women (15.9 vs. 12.0 %; p = 0.24). Patients who experienced FoD were on average approximately 3 years younger than patients who had not experienced FoD (p = 0.018). There were no significant differences with respect to sociodemographic characteristics (living alone, education level and employment). However, as can be seen in Table 1, patients who experienced FoD were significantly more likely to be smoker (p = 0.029), had a previous history of MI (p = 0.037), had experienced prodromal symptoms (p = 0.001) and had visited a cardiologist during the last 6 months before STEMI (p = 0.026).

Furthermore, patients who experienced FoD differed from their counterparts in several psychological characteristics: they were more likely to be anxious (p = 0.001), to express high negative affectivity (p = 0.013), to report low denial scores (p = 0.039) and to report suboptimal wellbeing (p = 0.001) in the last 6 months prior to STEMI.

There was no significant difference with respect to the objective severity of disease (Creatine Kinase, CRP as well as STEMI complications) as well as the majority of presenting symptoms in patients with FoD (Table 2).

Gender differences in factors associated with Fear of Death

As further shown in Table 1, male FoD patients in contrast to women experienced more prodromal symptoms (p = 0.001), had more often suffered from prior myocardial infarction (p = 0.045), and had more often visited a cardiologist 6 months prior to admission (p = 0.009). With regard to psychological factors, male patients with FoD were more likely to have high levels of generalized anxiety (p < 0.001) to report suboptimal wellbeing (p < 0.001), and to have lower denial scores (p = 049).

As can be seen in Table 2, male FoD patients were more likely to report that their symptoms met their previous expectations of STEMI (p = 0.037) and their perceived risk for STEMI to be serious (p < 0.001). Male FoD patients reported more shortness of breath (p = 0.05), while female FoD patients suffered more often of sweating (p = 0.012).

Predictors of fear of death

To identify the independent predictors of FoD, we performed a logistic regression analysis. Figure 1 displays the results of the multivariate logistic model. The most significant factors which independently predicted FoD in the overall population are: perceived STEMI symptom severity (OR = 3.7, p < 0.001), STEMI pain strength (OR = 2.3, p = 0.001), suboptimal wellbeing (OR = 2.2, p = 0.001), risk perception pre-STEMI (OR = 1.9, p = 0.01), negative affectivity (OR = 1.9, 95 % p = 0.01) and smoking (OR = 1.7, p = 0.05).

Forest plot demonstrating independent factors associated fear of death in STEMI patients: result of the multivariate logistic regression models, stratified for men and women (n = 572). In this multivariate model, candidate variables for inclusion include: age, smoking, history MI, prodromal symptoms, cardiologist visits, shortness of breath, sweating, pain strength, symptoms severity, risk perception, symptoms expectation, heart attribution, generalized anxiety disorders, negative affectivity, and wellbeing score

As further displayed in Fig. 1, the sex-stratified multivariate model confirmed the sex-specific heterogeneity in the factors associated with FoD. In men, factors related to the patient evaluation of symptoms were the most significant predictors of FoD, followed by psychological factors. In women, trait negative affect was the most significant predictor of FoD during STEMI, followed by perceived symptom severity and STEMI pain strength.

Impact of fear of death on prehospital delay (PHD)

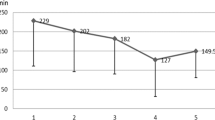

As shown in Fig. 2, the median PHD in patients who experienced FoD was significantly shorter than those who did not (median PHD 125 vs. 210 min, p = 0.001). However, this was only significant in men but not in women (p = 0.49).

Concerning the chance of early hospital arrival (<2 h), substantial differences between both sexes became also apparent in sex-stratified multiple regression models (see Table 3). Men who experienced FoD during STEMI had a twofold increased chance of early hospital arrival (<2 h) compared to men who did not (OR = 2.13, p = 0.005), while FoD showed no benefit in female patients with regard to early hospital arrival (OR = 0.95, p = 0.925). All multiple logistic regression results were replicated in models calculated with outcomes for delay less than four and six hours.

Additionally, as illustrated in Fig. 3, there was a statistically significant dose–response relationship in PHD times across the three levels of fear experienced by STEMI patients (p = 0.002, p(men) = 0.002, p(women) = 0.016), whereby the median delay times decrease as fear intensity increases (150, 193, and 241 min, respectively).

Factors related to patient behavioral responses to STEMI

As can be seen in Table 2, sex-stratified analysis of the behavioral response to STEMI disclosed the following differences: male FoD patients were less likely to wait until their symptoms relieved spontaneously (p = 0.006), and to drive themselves to the hospital (p = 0.018). In addition, they were more likely to be transported to the hospital by ambulance (p = 0.004). Interestingly, female FoD patients were more likely to phone emergency services (p = 0.03), while all other behavioral responses to STEMI showed no difference to non-FoD female patients.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation to comprehensively evaluate the characteristics of FoD and to assess its association with delay in a multicenter study of a homogeneous group of STEMI patients. Our findings indicate that FoD was experienced by a clinically meaningful minority of STEMI patients (15 %). Patient-reported pain strength and perceived symptom severity were the strongest independent factors associated with FoD in both men and women. Importantly, FoD has a strong beneficial impact on PHD in men but not in women.

Prevalence of patients who experienced fear of death

A total of 15 % had experienced FoD in a homogenous sample of STEMI patients. The prevalence of FoD in previous studies ranged from 4 % [9] to as high as 38.5 % [7] with the majority between 21.7 and 26.6 % [3, 4, 10]. The lowest prevalence was reported in a suspected AMI group of patients (50 % of them had even non-ischemic chest pain), while the highest was reported in a small sample of 83 patients. However, even the more reliable results were reported in a less homogenous group of patients including non-STEMI with a considerable time gap between presentation and FoD assessment.

Previous investigations [3, 20] found that women had an increased risk of FoD, which is intuitively expected as women are more likely to be psychologically distressed. However, we did not observe significant gender differences in terms of the frequency of FoD which is consistent with previous studies [4, 21]. Further analyses are needed who should highlight this conflicting evidence. Concerning the age distribution, we found that younger patients had a higher risk of FoD which is in line with a previous study [4]. Though, this was only significant in men but not in women (p = 0.02 vs. 0.265). It has been repeatedly shown that younger age is associated with more psychological maladaptation when facing a severe cardiac disease condition. Thus, the present finding is in line with an earlier investigation on this topic. The number of younger female patients (defined as <61 years) in the investigation is 8 and thus, it is most likely that the number of female patients compromises a possible positive association.

Characteristics of patients who experienced fear of death

During an acute STEMI, all the patients’ lives are under severe threat, yet only a clinically meaningful minority experienced FoD. Against the expectation that the variance in experiencing severe threat during STEMI is driven by the severity of underlying disease condition itself [22, 23], the present findings do not support this assumption as we did not observe any significant differences in markers of severe STEMI (CK or CRP) or post-MI complications.

In contrary, the present study draws a concise psycho-behavioral picture of the patients who are more vulnerable to experience FoD during the acute phase of MI. This vulnerable group of patients is more likely to be weakened by high levels of anxiety and negative affectivity and to be engaged and occupied by the disease process long ago before STEMI onset: they experienced more prodromal symptoms and more often consulted their cardiologists. Therefore, it is not unexpected that FoD patients were more likely to perceive STEMI symptoms as more severe, painful and life threatening than non-FoD patients.

Some pieces of this picture have been previously drawn, again in smaller and more heterogeneous patient populations: here, education [3, 4], living situation [4], pain intensity [3, 4] and attribution of symptoms to the heart [3, 10] were significantly associated with FoD.

Impact of fear of death on prehospital delay (PHD)

Male FoD patients had 2.1-fold chance of early hospital arrival (<2 h) compared to their counterparts. This finding in men along with the observed dose–response relationship between reported fear severity and delay contradicts our hypothesis that FoD is an immobilizing factor which impedes optimal performance. On the contrary, it becomes evident that the behavioral responses such as the utilization of emergency services contributed to shorter delay.

The observed beneficial impact of FoD on delay in men was not replicated in the female patients. This may be partly explained by lower awareness of MI risk [24, 25] in females and their social roles which promote efforts to preserve normal daily routine [26].

Strength and limitations

This is the first study investigating the impact of FoD on PHD in strictly defined population (STEMI). There are few study limitations that are worth considering. First, data on PHD were collected retrospectively from the patients, and thus there is potential for recall bias. However, all data were collected at bedside within a very narrow time frame after STEMI. We had relatively small numbers of women, so replications of these results in larger datasets are warranted. Furthermore, selection bias could have resulted from the excluding STEMI patients who died before reaching the hospital as well as recruiting patients only from a subset of all university hospitals and private clinics in Munich.

Implications for the clinic and future research

The present investigation contributes to our understanding of FoD which is considered in medical textbooks to be a prominent feature during STEMI but has only received limited scientific attention in recent years. The findings help to understand why patients—despite a similar underlying disease condition—experience this extremely distressing sentiment and it shows that—at least for male STEMI patients—FoD does not lead to fearful immobilization but guides them to optimal performance within the given critical time window. However, these patients pay a high price, including a greater risk of depression and anxiety after the attack [3]. This highlights the importance of effective patient aftercare, where the patient’s key concerns (including fear of death) should be directly and specifically addressed.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- STEMI:

-

ST segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

- FoD:

-

Fear of death

- PHD:

-

Prehospital delay

- MEDEA:

-

Munich examination of delay in patients experiencing acute myocardial infarction

References

Zobel C, Dorpinghaus M, Reuter H, Erdmann E (2012) Mortality in a cardiac intensive care unit. Clin Res Cardiol 101:521–524

Illmann A, Riemer T, Erbel R, Giannitsis E, Hamm C, Haude M, Heusch G, Maier LS, Munzel T, Schmitt C, Schumacher B, Senges J, Voigtlander T, Mudra H (2014) Disease distribution and outcome in troponin-positive patients with or without revascularization in a chest pain unit: results of the german cpu-registry. Clin Res Cardiol 103:29–40

Whitehead DL, Strike P, Perkins-Porras L, Steptoe A (2005) Frequency of distress and fear of dying during acute coronary syndromes and consequences for adaptation. Am J Cardiol 96:1512–1516

Steptoe A, Molloy GJ, Messerli-Burgy N, Wikman A, Randall G, Perkins-Porras L, Kaski JC (2011) Fear of dying and inflammation following acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J 32:2405–2411

Skinner DV (1997) Cambridge textbook of accident and emergency medicine. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lehto RH, Stein KF (2009) Death anxiety: an analysis of an evolving concept. Res Theory Nurs Pract 23:23–41

Carta MG, Sancassiani F, Pippia V, Bhat KM, Sardu C, Meloni L (2013) Alexithymia is associated with delayed treatment seeking in acute myocardial infarction. Psychother Psychosom 82:190–192

Gartner C, Walz L, Bauernschmitt E, Ladwig KH (2008) The causes of prehospital delay in myocardial infarction. Dtsch Arztebl Int 105:286–291

Johansson I, Stromberg A, Swahn E (2004) Factors related to delay times in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung 33:291–300

Kirchberger I, Heier M, Wende R, von Scheidt W, Meisinger C (2012) The patient’s interpretation of myocardial infarction symptoms and its role in the decision process to seek treatment: the monica/kora myocardial infarction registry. Clin Res Cardiol 101:909–916

Yerkes RM, Dodson JD (1908) The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. J Comp Neurol Psychol 18:459–482

Task Force on the management of STseamiotESoC, Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D (2012) Esc guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with st-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 33:2569–2619

Burnett RE, Blumenthal JA, Mark DB, Leimberger JD, Califf RM (1995) Distinguishing between early and late responders to symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 75:1019–1022

Fowers BJ (1992) The cardiac denial of impact scale: a brief, self-report research measure. J Psychosom Res 36:469–475

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the gad-7. Arch Intern Med 166:1092–1097

Bech P (2004) Measuring the dimension of psychological general well-being by the who-5. QoL Newsl 32:15–16

Hausteiner C, Klupsch D, Emeny R, Baumert J, Ladwig KH, Investigators K (2010) Clustering of negative affectivity and social inhibition in the community: prevalence of type d personality as a cardiovascular risk marker. Psychosom Med 72:163–171

Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, Martiny K, Bech P (2003) The internal and external validity of the major depression inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychol Med 33:351–356

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2008) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61:344–349

Kirchberger I, Heier M, Kuch B, Wende R, Meisinger C (2011) Sex differences in patient-reported symptoms associated with myocardial infarction (from the population-based monica/kora myocardial infarction registry). Am J Cardiol 107:1585–1589

Fischer D, Kindermann I, Karbach J, Herzberg PY, Ukena C, Barth C, Lenski M, Mahfoud F, Einsle F, Dannemann S, Bohm M, Kollner V (2012) Heart-focused anxiety in the general population. Clin Res Cardiol 101:109–116

Jespersen L, Abildstrom SZ, Hvelplund A, Prescott E (2013) Persistent angina: highly prevalent and associated with long-term anxiety, depression, low physical functioning, and quality of life in stable angina pectoris. Clin Res Cardiol 102:571–581

Meyer T, Hussein S, Lange HW, Herrmann-Lingen C (2014) Transient impact of baseline depression on mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease during long-term follow-up. Clin Res Cardiol 103:389–395

Mosca L, Hammond G, Mochari-Greenberger H, Towfighi A, Albert MA (2013) American Heart Association Cardiovascular D, Stroke in W, Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology CoE, Prevention CoCNCoHB. Fifteen-year trends in awareness of heart disease in women: results of a 2012 american heart association national survey. Circulation 127(1254–1263):e1229–e1251

Davis M, Diamond J, Montgomery D, Krishnan S, Eagle K, Jackson E (2015) Acute coronary syndrome in young women under 55 years of age: clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Clin Res Cardiol

Baxter SK, Allmark P (2013) Reducing the time-lag between onset of chest pain and seeking professional medical help: a theory-based review. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:15

Acknowledgments

This investigation was realized under the umbrella of the Munich Heart Alliance (MHA). Cooperating clinics in the city of Munich (Germany): Klinikum-Augustinum (Prof. Dr. Michael Block), Klinikum-Bogenhausen (Prof. Dr. Ellen Hoffmann), Deutsche-Herz-Zentrum München (Prof. Dr. Heribert Schunkert), Klinikum-Harlaching (Prof. Dr. Harald Kühl), Universitäts-Klinikum der LMU-Innenstadt (Prof. Dr. HaeYoung Sohn), Klinikum-Neuperlach (Prof. Dr. Harald Mudra), Universitäts-Klinikum Rechts der Isar-der-TUM (Prof. Dr. Karl-Ludwig Laugwitz) and Klinikum-Schwabing (Prof. Dr. Stefan Sack). This work was supported by a research grant of the Deutsche Herzstiftung (to Dr. Ladwig)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albarqouni, L., von Eisenhart Rothe, A., Ronel, J. et al. Frequency and covariates of fear of death during myocardial infarction and its impact on prehospital delay: findings from the multicentre MEDEA Study. Clin Res Cardiol 105, 135–144 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-015-0895-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-015-0895-3