Abstract

Introduction

For the past two decades, microsatellite instability (MSI) has been reported as a robust clinical biomarker associated with survival advantage attributed to its immunogenicity. However, MSI is also associated with high-risk adverse pathological features (poorly differentiated, mucinous, signet cell, higher grade) and exhibits a double-edged sword phenomenon. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the rate of dissemination and the prognosis of early and advanced stage colorectal cancer based on MSI status.

Methods

A systematic literature search of original studies was performed on Ovid searching MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, American College of Physicians ACP Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects DARE, Clinical Trials databases from inception of database to June 2019. Colorectal cancer, microsatellite instability, genomic instability and DNA mismatch repair were used as key words or MeSH terms. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline was followed. Data were pooled using a random-effects model with odds ratio (OR) as the effect size. Statistical analysis was performed using RevMan ver 5.3 Cochrane Collaboration.

Results

From 5288 studies, 136 met the inclusion criteria (n = 92,035; MSI-H 11,746 (13%)). Overall, MSI-H was associated with improved OS (OR, 0.81; 95% CI 0.73–0.90), DFS (OR, 0.73; 95% CI 0.66–0.81) and DSS (OR, 0.69; 95% CI 0.52–0.90). Importantly, MSI-H had a protective effect against dissemination with a significantly lower rate of lymph node and distant metastases. By stage, the protective effect of MSI-H in terms of OS and DFS was observed clearly in stage II and stage III. Survival in stage I CRC was excellent irrespective of MSI status. In stage IV CRC, without immunotherapy, MSI-H was not associated with any survival benefit.

Conclusions

MSI-H CRC was associated with an overall survival benefit with a lower rate of dissemination. Survival benefit was clearly evident in both stage II and III CRC, but MSI-H was neither a robust prognostic marker in stage I nor stage IV CRC without immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is a widely used biomarker in colorectal cancer (CRC). It is present in approximately 15% of CRCs. Currently, high MSI (MSI-H) status is used to identify patients for Lynch syndrome testing, to select patients with high-risk stage II CRC with adverse features for adjuvant treatment, to select stage IV CRC for immunotherapy and to guide prognosis. While its utility to identify Lynch syndrome is becoming universal, and it has increasingly been used to guide adjuvant therapy in high-risk stage II CRC and immunotherapy in stage IV CRCs, its utility as a robust biomarker of survival has not been widely adopted in clinical practice.

This is despite existing literature strongly supporting MSI as a robust biomarker of prognosis in CRC. Level 1 evidence thus far have reported that MSI status is useful in guiding prognosis in CRC patients, with MSI-H associated with enhanced survival [1, 2]. Furthermore, from tumour microenvironment studies, it is widely known that MSI-H is associated with immunogenicity, with MSI-H associated with increased tumour infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) [3,4,5,6,7] and TILs has been associated with better prognosis [3, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], decreased risk of lymph node metastases [18, 19] and distant metastases [20]. With two landmark meta-analyses reporting overall survival benefit associated with MSI [1, 2] and tumour biology and microenvironment studies demonstrating the immunogenicity of MSI-H CRCs, it may be difficult to understand why has MSI not been embraced universally as a robust clinical biomarker to guide prognosis in CRC.

This raises the question of whether the reported survival advantage conferred by MSI in the literature is observed in clinical practice. Closer inspection of the level 1 evidence reveals that a large majority of studies included in these meta-analyses [1, 2] have reported differences that were not statistically significant or only marginally significant.

While there is no doubt that MSI-H CRCs are immunogenic, MSI-H appears to exhibit a double-edged sword phenomenon. MSI-H CRCs are associated with an abundance of frameshift specific neo-peptides that, on one hand, is associated with the generation of the immune response [21,22,23]. On the other, MSI-H is also a marker of significantly more mutations. MSI-H CRCs are associated with poor differentiation [18, 24], larger diameter and increased likelihood to be higher grade, poorly differentiated or mucinous [25,26,27]. Several studies have reported that MSI-H may also be associated with an increased risk of locoregional recurrence after resection [28], increased risk of synchronous tumours [29, 30] and metachronous CRC [31]. Recent studies, including our own, have questioned the utility of MSI status as a universal clinical biomarker of enhanced survival [32].

In order to assess if MSI truly has any benefit, this meta-analysis examines the rate of dissemination associated with MSI-H CRCs. It also evaluates if MSI-H has a protective effect only in early stage, or if it maintains a survival benefit in advanced stage CRCs when it has already disseminated. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to have reported on the rate of dissemination and prognosis in early and advanced stage colorectal cancer based on MSI status. This meta-analysis also updates the existing literature on overall prognosis in MSI-H CRC and provides the most precise insight into the clinical value of MSI to date.

Methods

Search strategy

The present study was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines to investigate the association between MSI status, stage, age and prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. Electronic databases were searched including MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, American College of Physicians ACP Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects DARE, Clinical Trials databases from inception of database to July 2017, and this was updated in June 2019. To provide the most encompassing search strategy, we combined the terms microsatellite instability, DNA mismatch repair and colorectal cancer as either key words or MeSH terms (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The reference list of the included studies was reviewed to identify additional relevant studies that met inclusion criteria.

Selection criteria

Eligible studies that included CRC patients with survival outcomes presented by MSI status were considered for inclusion. Studies with cohorts reporting on MSI status in colorectal cancer either confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC), a range of mononucleotide and dinucleotide MSI markers in various combinations, and by both use of nucleotide markers and IHC, with at least 50 patients, ≥ 4 in each comparator group, and reporting on survival outcomes (OS, DFS, DSS). The status of adjuvant therapy was not an exclusion criteria. Studies evaluating the role of advancements in immunotherapy in CRC were excluded. We have previously reported on the potential role of immunotherapy in CRC [33]. Randomised controlled trials, non-randomised trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies were considered. Studies that reported a hazard ratio (HR) or odds ratio (OR) on OS, DFS, DSS based on MSI status were included. Where HR was not reported, HR was estimated from published time-to-event analyses based on the technique reported by Tierney et al. Studies where HR/OR was not reported on extractible were excluded. Exclusion criteria were non-comparative studies, case reports, abstract studies, studies with fewer than 50 patients (≤ 4 in each group) and studies where method of MSI status assignment was not provided. Studies reporting specifically on Lynch syndrome were excluded. Several studies combined MSI-L with MSS and these were included. Studies with overlapping populations were excluded unless the studies reported on different stages or on different survival outcomes. In this case, these studies were included for systematic review and only included where reporting on different stage or outcome categories.

Data extraction, quality appraisal and risk of bias

Article titles and abstracts were screened by J.T. and K.P. independently, with inclusion for full-text review where there was a consensus between J.T and K.P. Where articles were identified for inclusion by only one investigator, these were discussed and resolved by consensus to determine if the study met inclusion criteria. Where full texts were not available or only conference abstracts were available, these were excluded from the meta-analysis. Articles were appraised using a standard protocol. Data extracted included OS, DFS, DSS, mean age (median if mean not available) of cohort based on MSI-H status, age index (MSI-H CRC age/MSS CRC age), stage (including number of patients with MSI-H in each stage), percentage of cohort with MSI-H, MSS, proximal (right) vs. distal (left) CRC, rectal cancer and where reported, percentage of cohort with BRAF mutation. Stratified and non-stratified OS, DFS and DSS were reported. HR and OR reported by the studies were used when available. In several studies, the HR was estimated from published time-to-event-analysis using the technique by Tierney et al. Where HR/OR was not available or estimable for one of OS, DFS, DSS, these studies were excluded from analysis. Quality appraisal of studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for risk of bias assessment. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was chosen over the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias assessment tool as majority of the studies were non-RCTs, and of the RCTs included, majority were secondary analysis of MSI status data rather than MSI status being the primary endpoint.

Statistical analysis

Odds ratio (ORs) were used as summary statistics. We used a random-effects model. χ2 test was used to evaluate the heterogeneity between trials. The I2 statistic was used to estimate the variation across studies owing to heterogeneity rather than chance. Values greater than 50% were considered significant heterogeneity. For I2 values > 50%, methodological and extractible clinical factors were examined to assess reasons for heterogeneity, but specific analyses were not possible due to raw data not being available. All p values were 2-sided, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. For relevant stage data, analysis was performed on STATA (Stata MP, version 15; StataCorp LP).

Results

Search results

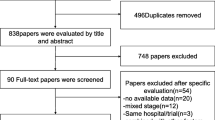

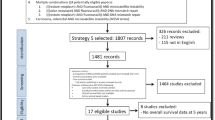

A total of 5288 studies were identified through electronic database searches. After inclusion of 18 studies identified by additional sources and exclusion of duplicates, 3739 potentially relevant articles were retrieved. After applying the selection criteria, 136 articles were included for qualitative and quantitative synthesis (Fig. 1). Detailed study baseline stage characteristics have been summarised in Table 1, and risk of bias assessment in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Majority of studies included were cohort studies (non-RCTs), and the included RCTs reported MSI status in subset analysis rather than as a primary endpoint.

Baseline patient characteristics

There was a total of 92,035 patients included (MSI-H 11746 (13%)). Of the studies which reported a mean age, the mean age ranged from 41.3 to 74 for MSI-H group, 43.5 to 70.4 for the MSS group. Thirteen studies reported a mean (or median where mean not available) age < 60, 31 studies reported a mean age ≥ 60 for their MSI-H CRC cohort. Percentage of BRAF mutation within the cohort of MSI-H CRC was reported in 34 studies. The range was 14–72%.

Rate of dissemination (lymph node and distant metastasis)

A total of 118 of the 136 studies (MSI = 8681) included in this meta-analysis had stage-specific data. A total of 4393 (51%) patients were stage I/II, 3676 (42%) stage III and 616 (7%) stage IV CRC. However, this data included studies reporting on single stage, early (I/II) or advanced (III, IV) CRC as well as all stages. The likelihood of progression cannot be estimated with the inclusion of studies which reported specifically on early or advanced or single stage CRC, as this would skew the data due to selection bias.

To determine the likelihood of disease progression (lymph node metastases ± distant metastases) associated with MSI, only studies which included at least stage II and III CRC in their study cohort were pooled for stage data. A total of 77 studies (MSI = 6134) included at least stage II and III CRC patients. A total of 3692 (60%) patients were stage I/II, 2179 (36%) stage III and 263 (4%) stage IV. The ratio of early stage (I/II): advanced stage (III/IV) was 60%:40%.

Only 43 studies (MSI = 3150) included patients with I, II, III, IV or II, III, IV CRC. A total of 1928 (61%) patients were stage I/II, 959 (30%) stage III and 263 (8%) stage IV CRC. The stage I/II:III/IV ratio was approximately 60%:40%.

From both analyses, the ratio of early:advanced CRC was approximately 60:40%—i.e. more early than advanced CRC associated with MSI-H.

Overall prognosis

Overall, 96 studies provided OS pooled data with OS overall estimate of OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.73–0.90, p < 0.00001; I2 = 70% (refer to Fig. 2). Sixty studies provided DFS data with DFS overall estimate of OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.66–0.81, p < 0.00001; I2 = 71% (Fig. 3). Twenty-nine studies provided DSS data with DSS overall estimate of 0.69; 95% CI 0.52–0.90, p = 0.007; I2 = 69% (Fig. 4). Overall, MSI-H was associated with better OS, DFS and DSS.

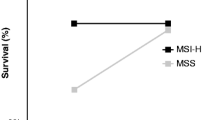

Prognosis in early and late stage

For stage I, results from 4 studies showed no difference in OS between stage I MSI-H and MSS CRC: OS (OR, 1.33; 95% CI 0.41–4.39; p = 0.63; I2 = 11%). Two studies were suitable for pooling to provide DFS data (OR, 0.41; 95% CI 0.17–1.00; p = 0.05; I2 = 0%). Two studies reported on DSS (OR, 0.59; 0.27–1.33; p = 0.08; I2 = 0%). There was not a statistically significant difference in OS, DFS and DSS in stage I CRC. It was unclear whether this was partly due to the sparsity of data available on MSI status in stage I CRC, but survival was excellent irrespective of MSI status in stage I CRC.

For stage II CRC, 26 studies provided OS data. The estimate for OS for stage II CRC was OR, 0.56; 95% CI 0.36–0.89; p = 0.01; I2 = 93%. Twenty studies provided DFS data for stage II CRC (OR, 0.59; p < 0.0001; 95% CI 0.46–0.76; I2 = 60%). Only four studies reported on stage II CRC DSS (OR, 0.55; 95% CI 0.23–1.34; p = 0.19; I2 = 47%). For DSS, there was a trend to benefit but this was statistically insignificant and this was likely due to the limited data available for DSS in stage II CRC. Both the estimates for OS and DFS demonstrated a survival advantage for stage II MSI-H CRC.

23 studies provided OS data with the OS for stage III CRC estimated to be OR, 0.74; 0.60–0.91; p = 0.005; I2 = 57%). Nineteen studies reported on DFS in stage III CRC. The estimate for DFS in stage III CRC was OR, 0.71 (95% CI 0.63–0.80; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0%). For DSS, there was limited data with significant heterogeneity with only 7 studies reporting this outcome for stage III CRC. This showed no difference in DSS between the MSI-H and MSS CRC (OR, 1.09; 0.76–1.55; p = 0.64; I2 = 52%). Both the estimates for OS and DFS reported a statistically significant survival benefit for stage III MSI-H CRC.

Eleven studies reported no difference in OS between stage IV MSI-H and MSS CRC (OR, 1.05; 95% CI 0.81–1.36; p = 0.70; I2 = 68%). Only three studies reported on DFS in stage IV CRC. The estimate for DFS was OR, 0.63; 95% CI 0.32–1.22; p = 0.17; I2 = 71%). Three studies reported data for DSS in stage IV CRC with no statistically significant difference between the two groups (OR, 0.75; 95% CI 0.41–1.38; p = 0.35; I2 = 0). There was no benefit in OS, DFS nor DSS in stage IV CRC based on MSI status.

While studies on immunotherapy trials were excluded in this present meta-analysis (as not within the scope of this meta-analysis), we have previously performed a systematic review of immunotherapy for stage IV metastatic CRC which demonstrated a survival advantage with immunotherapy for MSI-H CRC [33] and results from this present meta-analysis on stage IV metastatic CRC as well as the potential role of immunotherapy in stage IV MSI-H CRC will be discussed in the discussion.

The OS, DFS and DSS by stage has been summarised in Table 2 and forest plot analysis of OS, DFS and DSS (overall and by stage) has been provided in Figs. 5, 6 and 7.

Other factors influencing prognosis

Age (< 60/≥ 60)

Studies were divided into two subgroups (< 60/≥ 60) based on the mean age of the MSI-H cohort. In studies where a mean age was not reported, the median age was used. Thirteen studies reported a mean or median age < 60, 31 studies reported a mean or median age ≥ 60. There was a statistically significant benefit in OS associated with MSI-H status in studies with mean/median age < 60 (OR, 0.69; 95% CI 0.58–0.84; p = 0.0002; I2 = 37%). However, where the mean/median age was ≥ 60, there was trend to better OS, but was not statistically significant (OR, 0.84; 95% CI 0.70–1.02; p = 0.07; I2 = 74%) (refer to eFigure 1). In this meta-analysis, the survival benefit conferred by MSI status was greatest in younger cohorts where the median (mean) age of the cohort was < 60.

BRAF status

Percentage of BRAF mutation within the cohort of MSI-H CRC was reported in 34 studies. The range was 14–72%. The data were not statistically significant but there was a trend to better OS and DFS with studies reporting a lower percentage of BRAF mutation in the MSI-H cohort.

High grade/mucinous/signet cell/poor differentiation

High grade CRC was reported specifically in eight studies (mucinous n = 3, signet cell n = 2, poor differentiation n = 3). With the limited data available, a survival benefit associated with MSI-H was not detected in high grade, poorly differentiated CRC that were mucinous or with signet cell (OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.64–1.28; p = 0.58; I2 = 28%).

Sidedness and rectum

MSI-H status in both right and left side colon cancers were associated with improved OS (Right: OR, 0.39; 95% CI 0.30–0.51; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0%; Left: OR. 0.40; 95% CI 0.30–0.53; p < 0.00001; I2 = 0%). An analysis comparing percentage of right (proximal) and left (distal) colon cancer with OS showed no difference in OS between right and left side in patients with MSI-H colon cancer. The survival benefit associated with MSI-H was statistically significant for both right and left colon.

The findings for rectal cancer was based on limited studies and was not statistically significant (OR, 0.93; 95% CI 0.35–2.49; p = 0.88; I2 = 75%).

Only a limited number of studies were available for analysis on other factors influencing prognosis, and these results must be interpreted carefully.

Publication bias

Funnel plot analysis was produced for OS, DFS and DSS (overall, early and advanced stage). (refer to Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13). There was no significant funnel plot asymmetry and publication bias was not significant.

Discussion

Level 1 evidence to date has reported better survival associated with MSI-H in CRC [1, 2]. In 2010, Guastadisegni et al. concluded that patients with stage I-IV MSI-H CRC appear to have better survival and better outcome found in terms of OS, DSS and DFS [2]. However, the survival advantage observed in clinical practice with this CRC phenotype has not been as robust and comprehensive as that reported in the above meta-analyses. This present meta-analysis attempts to explain differences between the evidence in the existing literature and in clinical practice.

Rate of dissemination (lymph node and distant metastasis)

This meta-analysis demonstrated that MSI-H was associated with a lower incidence of disease progression to lymph node and distant metastases. From examining studies reporting on at least stage II and III CRC patients as well as stage I/II/III/IV or II/III/IV, the ratio of early (I/II): late (III/IV) MSI-H CRC from appropriate studies was 60%:40% (ratio 1.5) respectively—i.e. more MSI-H CRC was detected and managed at early stage.

In comparison, CRC statistics from the 2010–2016 National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data reports localised disease (I/II 38%), regional (III 35%) and distant (IV 22%) metastases (unknown in 4%) associated with CRC [34]. The stage I/II:III/IV ratio based on 2010–2016 SEER data was 40%:60% (ratio 0.67)—i.e. more CRC of any phenotype detected at advanced stage (refer to Table 3).

The ratio of early to advanced cancer for MSI-H CRC was approximately double the ratio from the SEER data, demonstrating a lower incidence of progression to lymph node and distant metastases with MSI-H CRC when compared to an international database reporting on all phenotypes of CRC. There was significantly less progression to stage IV disease in MSI-H CRC. This finding of decreased likelihood of dissemination in MSI-H CRC is similar to findings from studies such as by Malesci et al. [35] which demonstrated an association between MSI-H and decreased risk of dissemination of cancer.

Overall prognosis and prognosis in early and late stage

This meta-analysis demonstrated an overall benefit in terms of OS, DFS and DSS. The protective effect of MSI-H was observed most clearly in stage II and III with better OS and DFS demonstrated in stage II and III CRC. There was not in a survival benefit in stage I (excellent survival irrespective of MSI status) and nor in stage IV CRC (without immunotherapy). Better DFS in stage II and III reported in this meta-analysis was consistent with the current literature reporting lower risk of relapse [35].

The lack of benefit in stage I may be explained by the overall excellent prognosis in stage I CRC for both MSI-H and MSS, but also may be partly due to the limited studies reporting on stage I MSI-H CRC. The lack of benefit in stage IV CRC (without immunotherapy) may be explained by the phenomenon of TILs exhaustion [33, 36]. Results from immunotherapy trials in metastatic MSI-H CRCs have been promising [33], but not within the scope of this meta-analysis. We have, however, previously reported on the benefits of immunotherapy on metastatic stage IV CRC [33] and the findings of this meta-analysis thus underscores the importance of immunotherapy for metastatic stage IV CRC, as without it, stage IV MSI-H CRC appeared to have lost its immunogenicity.

In terms of DSS, there was better prognosis overall. However, by stage, there was no statistically significant survival advantage. This was likely due to the limited studies available reporting on DSS by stage rather than a true effect. It is important to understand that DSS censor patients who have died from causes other than the disease being studied. Deaths from other causes (competing causes of death) are removed (in the same way that people who are lost to follow-up are removed). Patients with sporadic MSI-H were older and thus more likely to die from other causes, and this may have partly contributed to DSS findings reported in this meta-analysis.

Other factors influencing prognosis

Age (< 60/≥ 60)

Studies with a younger MSI-H CRC cohort (< 60) reported better OS associated with MSI. While this meta-analysis reported mainly on sporadic CRC, Lynch syndrome has traditionally been underdiagnosed and studies included in this meta-analysis may have included Lynch syndrome patients unknowingly (younger patients with BRAF wild type) as genetic testing may not have been performed in a large majority of cases. Patients with Lynch syndrome have a hereditary predisposition for colorectal cancer with early age of onset, with a median age of colorectal cancer diagnosis between the age of 40–50 years old. In a study by Schofield et al. looking at patients <60 years of age, 105/1344 patients had MSI-H. In these MSI-H cases, germline mutation in MMR associated with Lynch syndrome was estimated to be 89% (< 30 years), 83% (30–39), 68% (40–49) and 17% (50–59) [37]. A study by Stigliano et al. reported that the median age for diagnosis of a primary CRC was 61 years old whereas it was approximately 47 years for Lynch syndrome [38]. Within the literature, Lynch syndrome has been associated with better survival [38, 39]. This meta-analysis showed that younger patients with MSI-H CRC irrespective of Lynch syndrome diagnosis were associated with improved survival. It is unclear if this may be due to an underdiagnosis of Lynch syndrome patients in younger patients with MSI-H CRC.

BRAF status

In this study, there was a trend to better OS and DFS in studies with a lower percentage of BRAF mutation within their MSI-H cohort. However, this was not statistically significant. This is in line with the current literature which suggests that BRAFV600E mutation is associated with worse prognosis in CRC. BRAFV600E testing is also a useful method for triaging MSI-H CRC patients for genetic testing for Lynch syndrome [40, 41]. The detection of BRAFV600E mutation in MSI-H CRC nearly always excludes Lynch syndrome. Absence of BRAF mutation in MSI-H CRC is associated with Lynch syndrome in approximately 60–70% [42]. As with age, it is unclear if the survival advantage of BRAF wild type in MSI-H CRC was influenced by an underdiagnosis of Lynch syndrome patients (which have a better prognosis) in the younger patients with MSI-H CRC.

High grade/poorly differentiated/mucinous

Only eight studies included in our meta-analysis reported survival outcomes specifically on high grade (signet cell, mucinous and poor differentiation) MSI-H CRC. A subset analysis demonstrated no difference in OS between MSI-H and MSS in patients with high grade CRC. Within the current literature, it is unclear if high grade MSI-H CRC is associated with better survival as studies have reported a range of results [26, 43,44,45]. This meta-analysis did not find a survival advantage in high grade CRC based on MSI status; however, this result was based on a limited number of studies.

Right colon/left colon/rectum

MSI-H colon cancers are more likely to be right-sided when compared to MSS colon cancers [46]. Furthermore, LS cancers are also more likely to be right-sided (85% right-sided) than sporadic (57% right-sided) MSI-H CRC [38]. From this present meta-analysis, as well as the meta-analysis by Popat et al. and Guastadisegni et al. [1, 2], which have all reported improved OS with MSI-H CRC, it would be reasonable to assume that right-sided colon cancer would have better survival outcome than the left as a greater proportion are associated with MSI. However, recent studies [47,48,49] which includes a meta-analysis on right vs. left-sided colorectal cancer [49] as well as a Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database analysis [48] have reported that survival outcome is better for left-sided than right-sided colon cancer. This meta-analysis showed better survival outcomes associated with MSI in both right and left colon cancer, but it does not explain why survival rates associated with left-sided cancers are better than right in general.

There were limited studies reporting on MSI status in rectal cancer. This meta-analysis did not show a survival benefit for MSI-H rectal cancers, but with the limited studies available, these results must be interpreted with caution. In any case, most rectal cancers are MSS. Within the current literature, there have been studies reporting both lower survival in MSI-H rectal cancer [50] as well as no difference [51].

Limitations

There were several limitations in this present meta-analysis. Firstly, there were only a limited number of studies reporting on stage I and IV, DSS and other factors influencing prognosis. Included studies were predominantly observational cohort studies and retrospective in nature and this contributed to the heterogeneity seen within this meta-analysis. There was insufficient data on genetic testing for Lynch syndrome to include in quantitative analysis, and it is likely that there was underreporting of Lynch syndrome in studies on MSI. Despite its limitations, this meta-analysis is the most comprehensive and largest meta-analysis on MSI status in CRC to date and provides valuable information on the rate of dissemination and prognosis of early and late stage CRC based on MSI status.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis has confirmed an overall protective effect associated with microsatellite instability with overall improved survival (OS, DFS, DSS). There was also a lower rate of dissemination to lymph node and distant metastases associated with MSI-H CRC. By stage, the survival benefit associated with MSI-H is greatest in stage II and III CRC. Stage I CRC has excellent prognosis irrespective of MSI status, and MSI-H was not associated with any survival advantage without immunotherapy in stage IV CRC which may be explained by a phenomenon known as TILs exhaustion in late stage. Survival benefit associated with MSI-H appeared to be enhanced in younger patients <60 and other factors such as BRAF status, grade and tumour location may influence survival associated with MSI-H, but these results were based on a limited number of studies and must be interpreted judiciously.

References

Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS (2005) Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol 23(3):609–618. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2005.01.086

Guastadisegni C, Colafranceschi M, Ottini L, Dogliotti E (2010) Microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and response to therapy: a meta-analysis of colorectal cancer survival data. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 46(15):2788–2798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.009

Michael-Robinson JM, Biemer-Huttmann A, Purdie DM, Walsh MD, Simms LA, Biden KG, Young JP, Leggett BA, Jass JR, Radford-Smith GL (2001) Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes and apoptosis are independent features in colorectal cancer stratified according to microsatellite instability status. Gut 48(3):360–366

Kim JH, Kang GH (2014) Molecular and prognostic heterogeneity of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 20(15):4230–4243. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4230

Greenson JK, Bonner JD, Ben-Yzhak O, Cohen HI, Miselevich I, Resnick MB, Trougouboff P, Tomsho LD, Kim E, Low M, Almog R, Rennert G, Gruber SB (2003) Phenotype of microsatellite unstable colorectal carcinomas: well-differentiated and focally mucinous tumors and the absence of dirty necrosis correlate with microsatellite instability. Am J Surg Pathol 27(5):563–570

Smyrk TC, Watson P, Kaul K, Lynch HT (2001) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are a marker for microsatellite instability in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 91(12):2417–2422

Tougeron D, Fauquembergue E, Rouquette A, Le Pessot F, Sesboue R, Laurent M, Berthet P, Mauillon J, Di Fiore F, Sabourin JC, Michel P, Tosi M, Frebourg T, Latouche JB (2009) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability are correlated with the number and spectrum of frameshift mutations. Mod Pathol 22(9):1186–1195. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.80

Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, Mlecnik B, Kirilovsky A, Nilsson M, Damotte D, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Galon J (2005) Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 353(25):2654–2666. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa051424

Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Bindea G, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F, Galon J (2011) Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol 29(6):610–618. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.30.5425

Ling A, Edin S, Wikberg ML, Oberg A, Palmqvist R (2014) The intratumoural subsite and relation of CD8(+) and FOXP3(+) T lymphocytes in colorectal cancer provide important prognostic clues. Br J Cancer 110(10):2551–2559. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.161

Svennevig JL, Lunde OC, Holter J, Bjorgsvik D (1984) Lymphoid infiltration and prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 49(3):375–377

Jass JR (1986) Lymphocytic infiltration and survival in rectal cancer. J Clin Pathol 39(6):585–589

Shunyakov L, Ryan CK, Sahasrabudhe DM, Khorana AA (2004) The influence of host response on colorectal cancer prognosis. Clin Colorectal Cancer 4(1):38–45

Dahlin AM, Henriksson ML, Van Guelpen B, Stenling R, Oberg A, Rutegard J, Palmqvist R (2011) Colorectal cancer prognosis depends on T-cell infiltration and molecular characteristics of the tumor. Mod Pathol 24(5):671–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.234

Chiba T, Ohtani H, Mizoi T, Naito Y, Sato E, Nagura H, Ohuchi A, Ohuchi K, Shiiba K, Kurokawa Y, Satomi S (2004) Intraepithelial CD8+ T-cell-count becomes a prognostic factor after a longer follow-up period in human colorectal carcinoma: possible association with suppression of micrometastasis. Br J Cancer 91(9):1711–1717. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602201

Zlobec I, Lugli A, Baker K, Roth S, Minoo P, Hayashi S, Terracciano L, Jass JR (2007) Role of APAF-1, E-cadherin and peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration in tumour budding in colorectal cancer. J Pathol 212(3):260–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.2164

Prall F, Duhrkop T, Weirich V, Ostwald C, Lenz P, Nizze H, Barten M (2004) Prognostic role of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in stage III colorectal cancer with and without microsatellite instability. Hum Pathol 35(7):808–816

Kazama Y, Watanabe T, Kanazawa T, Tanaka J, Tanaka T, Nagawa H (2007) Microsatellite instability in poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas of the colon and rectum: relationship to clinicopathological features. J Clin Pathol 60(6):701–704. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2006.039081

Lamberti C, Lundin S, Bogdanow M, Pagenstecher C, Friedrichs N, Buttner R, Sauerbruch T (2007) Microsatellite instability did not predict individual survival of unselected patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Color Dis 22(2):145–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-006-0131-8

Buckowitz A, Knaebel HP, Benner A, Blaker H, Gebert J, Kienle P, von Knebel DM, Kloor M (2005) Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer is associated with local lymphocyte infiltration and low frequency of distant metastases. Br J Cancer 92(9):1746–1753. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602534

Schwitalle Y, Kloor M, Eiermann S, Linnebacher M, Kienle P, Knaebel HP, Tariverdian M, Benner A, von Knebel DM (2008) Immune response against frameshift-induced neopeptides in HNPCC patients and healthy HNPCC mutation carriers. Gastroenterology 134(4):988–997. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.015

Linnebacher M, Gebert J, Rudy W, Woerner S, Yuan YP, Bork P, von Knebel DM (2001) Frameshift peptide-derived T-cell epitopes: a source of novel tumor-specific antigens. Int J Cancer J Intl Cancer 93(1):6–11

Shapira S, Fokra A, Arber N, Kraus S (2014) Peptides for diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Curr Med Chem 21(21):2410–2416

Xiao H, Yoon YS, Hong SM, Roh SA, Cho DH, Yu CS, Kim JC (2013) Poorly differentiated colorectal cancers: correlation of microsatellite instability with clinicopathologic features and survival. Am J Clin Pathol 140(3):341–347. https://doi.org/10.1309/ajcp8p2dynkgrbvi

Thibodeau SN, Bren G, Schaid D (1993) Microsatellite instability in cancer of the proximal colon. Science (New York, NY) 260(5109):816–819

Yoon YS, Kim J, Hong SM, Lee JL, Kim CW, Park IJ, Lim SB, Yu CS, Kim JC (2015) Clinical implications of mucinous components correlated with microsatellite instability in patients with colorectal cancer. Color Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.13027

Karahan B, Argon A, Yildirim M, Vardar E (2015) Relationship between MLH-1, MSH-2, PMS-2,MSH-6 expression and clinicopathological features in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8(4):4044–4053

Soreide K, Slewa A, Stokkeland PJ, van Diermen B, Janssen EAM, Soreide JA, Baak JPA, Korner H (2009) Microsatellite instability and DNA ploidy in colorectal cancer: potential implications for patients undergoing systematic surveillance after resection. Cancer 115(2):271–282. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24024

Yun HR, Yi LJ, Cho YK, Park JH, Cho YB, Yun SH, Kim HC, Chun HK, Lee WY (2009) Double primary malignancy in colorectal cancer patients--MSI is the useful marker for predicting double primary tumors. Int J Color Dis 24(4):369–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-541-x

Hu H, Chang DT, Nikiforova MN, Kuan SF, Pai RK (2013) Clinicopathologic features of synchronous colorectal carcinoma: a distinct subset arising from multiple sessile serrated adenomas and associated with high levels of microsatellite instability and favorable prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol 37(11):1660–1670. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31829623b8

Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Seppala TT, Jarvinen HJ, Mecklin JP (2017) Subtotal colectomy for colon cancer reduces the need for subsequent surgery in Lynch syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum 60(8):792–799. https://doi.org/10.1097/dcr.0000000000000802

Toh J, Chapuis PH, Bokey L, Chan C, Spring KJ, Dent OF (2017) Competing risks analysis of microsatellite instability as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 104(9):1250–1259. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10542

Toh JW, de Souza P, Lim SH, Singh P, Chua W, Ng W, Spring KJ (2016) The potential value of immunotherapy in colorectal cancers: review of the evidence for programmed death-1 inhibitor therapy. Clin Colorectal Cancer 15(4):285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2016.07.007

Surveillance Research Program; National Cancer Institute. EaERP. [Accessed September 20, 2020]; Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov

Malesci A, Laghi L, Bianchi P, Delconte G, Randolph A, Torri V, Carnaghi C, Doci R, Rosati R, Montorsi M, Roncalli M, Gennari L, Santoro A (2007) Reduced likelihood of metastases in patients with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13(13):3831–3839. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-0366

Zinselmeyer BH, Heydari S, Sacristan C, Nayak D, Cammer M, Herz J, Cheng X, Davis SJ, Dustin ML, McGavern DB (2013) PD-1 promotes immune exhaustion by inducing antiviral T cell motility paralysis. J Exp Med 210(4):757–774. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20121416

Schofield L, Watson N, Grieu F, Li WQ, Zeps N, Harvey J, Stewart C, Abdo M, Goldblatt J, Iacopetta B (2009) Population-based detection of Lynch syndrome in young colorectal cancer patients using microsatellite instability as the initial test. Int J Cancer J Intl Cancer 124(5):1097–1102. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23863

Stigliano V, Assisi D, Cosimelli M, Palmirotta R, Giannarelli D, Mottolese M, Mete LS, Mancini R, Casale V (2008) Survival of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer patients compared with sporadic colorectal cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 27(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-9966-27-39

Drescher KM, Sharma P, Lynch HT (2010) Current hypotheses on how microsatellite instability leads to enhanced survival of Lynch syndrome patients. Hindawi Publishing Corporation, 410 Park Avenue, 15th Floor, 287 pmb, New York NY 10022, United States http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed12&NEWS=N&AN=359172101. Accessed (Drescher) Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, Creighton University, School of Medicine, Omaha, NE 68178, United States 2010

Toon CW, Walsh MD, Chou A, Capper D, Clarkson A, Sioson L, Clarke S, Mead S, Walters RJ, Clendenning M, Rosty C, Young JP, Win AK, Hopper JL, Crook A, Von Deimling A, Jenkins MA, Buchanan DD, Gill AJ (2013) BRAFV600E immunohistochemistry facilitates universal screening of colorectal cancers for lynch syndrome. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 530 Walnut Street,P O Box 327, Philadelphia PA 19106-3621, United States http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed15&NEWS=N&AN=369870141. Accessed (Toon, Clarkson, Sioson, Gill) Department of Anatomical Pathology, Darlinghurst, Australia 37

Toon CW, Chou A, Desilva K, Chan J, Patterson J, Clarkson A, Sioson L, Jankova L, Gill AJ (2014) BRAFV600E immunohistochemistry in conjunction with mismatch repair status predicts survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Nature Publishing Group, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS, United Kingdom http://www.nature.com/modpathol/index.htmlhttp://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed16&NEWS=N&AN=52834712. Accessed (Toon, Clarkson, Sioson, Gill) Department of Cancer Diagnosis and Pathology, Kolling Institute of Medical Research, St Leonards, NSW, Australia 27

Newton K, Jorgensen NM, Wallace AJ, Buchanan DD, Lalloo F, McMahon RF, Hill J, Evans DG (2014) Tumour MLH1 promoter region methylation testing is an effective prescreen for lynch syndrome (HNPCC). J Med Genet 51(12):789–796. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102552

Messerini L, Ciantelli M, Baglioni S, Palomba A, Zampi G, Papi L (1999) Prognostic significance of microsatellite instability in sporadic mucinous colorectal cancers. Hum Pathol 30(6):629–634

Kim SH, Shin SJ, Lee KY, Kim H, Kim TI, Kang DR, Hur H, Min BS, Kim NK, Chung HC, Roh JK, Ahn JB (2013) Prognostic value of mucinous histology depends on microsatellite instability status in patients with stage III colon cancer treated with adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol 20(11):3407–3413. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3169-1

Verhulst J, Ferdinande L, Demetter P, Ceelen W (2012) Mucinous subtype as prognostic factor in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Clin Pathol 65(5):381–388. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200340

Missiaglia E, Jacobs B, D'Ario G, Di Narzo AF, Soneson C, Budinska E, Popovici V, Vecchione L, Gerster S, Yan P, Roth AD, Klingbiel D, Bosman FT, Delorenzi M, Tejpar S (2014) Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Ann Oncol 25(10):1995–2001. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu275

Lim DR, Kuk JK, Kim T, Shin EJ (2017) Comparison of oncological outcomes of right-sided colon cancer versus left-sided colon cancer after curative resection: which side is better outcome? Medicine 96(42):e8241. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000008241

Ulanja MB, Rishi M, Beutler BD, Sharma M, Patterson DR, Gullapalli N, Ambika S (2019) Colon Cancer Sidedness, Presentation, and Survival at Different Stages. J Oncol 2019:4315032. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4315032

Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Borgonovo K, Ghidini M, Turati L, Dallera P, Passalacqua R, Sgroi G, Barni S (2017) Prognostic survival associated with left-sided vs right-sided colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 3(2):211–219. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4227

Jernvall P, Makinen MJ, Karttunen TJ, Makela J, Vihko P (1999) Microsatellite instability: impact on cancer progression in proximal and distal colorectal cancers. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 35(2):197–201

Meng WJ, Sun XF, Tian C, Wang L, Yu YY, Zhou B, Gu J, Xia QJ, Li Y, Wang R, Zheng XL, Zhou ZG (2007) Microsatellite instability did not predict individual survival in sporadic stage II and III rectal cancer patients. Oncology 72(1–2):82–88. https://doi.org/10.1159/000111107

Alex AK, Siqueira S, Coudry R, Santos J, Alves M, Hoff PM, Riechelmann RP (2017) Response to chemotherapy and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer with DNA deficient mismatch repair. Clin Colorectal Cancer 16(3):228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2016.11.001

Aparicio T, Schischmanoff O, Poupardin C, Soufir N, Angelakov C, Barrat C, Levy V, Choudat L, Cucherousset J, Boubaya M, Lagorce C, Guetz GD, Wind P, Benamouzig R (2013) Deficient mismatch repair phenotype is a prognostic factor for colorectal cancer in elderly patients. Dig Liver Dis 45(3):245–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2012.09.013

Andrici J, Farzin M, Sioson L, Clarkson A, Watson N, Toon CW, Gill AJ (2016) Mismatch repair deficiency as a prognostic factor in mucinous colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol 29(3):266–274. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.159

Bae JM, Kim JH, Rhee YY, Cho NY, Kim TY, Kang GH (2015) Annexin A10 expression in colorectal cancers with emphasis on the serrated neoplasia pathway. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 21(33):9749–9757. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i33.9749

Banerjea A, Hands RE, Powar MP, Bustin SA, Dorudi S (2009) Microsatellite and chromosomal stable colorectal cancers demonstrate poor immunogenicity and early disease recurrence. Color Dis 11(6):601–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01639.x

Barault L, Charon-Barra C, Jooste V, de la Vega MF, Martin L, Roignot P, Rat P, Bouvier AM, Laurent-Puig P, Faivre J, Chapusot C, Piard F (2008) Hypermethylator phenotype in sporadic colon cancer: study on a population-based series of 582 cases. Cancer Res 68(20):8541–8546. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-1171

Barrasa Shaw A, Lopez-Guerrero JA, Calatrava Fons A, Garcia-Casado Z, Alapont Olavarrieta V, Campos Manez J, Vazquez Albaladejo C (2009) Value of the identification of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Clin Translational Oncol 11(7):465–469

Benatti P, Gafa R, Barana D, Marino M, Scarselli A, Pedroni M, Maestri I, Guerzoni L, Roncucci L, Menigatti M, Roncari B, Maffei S, Rossi G, Ponti G, Santini A, Losi L, Di Gregorio C, Oliani C, Ponz de Leon M, Lanza G (2005) Microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. Clin Cancer Res 11(23):8332–8340. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-05-1030

Bertagnolli MM, Redston M, Compton CC, Niedzwiecki D, Mayer RJ, Goldberg RM, Colacchio TA, Saltz LB, Warren RS (2011) Microsatellite instability and loss of heterozygosity at chromosomal location 18q: prospective evaluation of biomarkers for stages II and III colon cancer--a study of CALGB 9581 and 89803. J Clin Oncol 29(23):3153–3162. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.33.0092

Birgisson H, Edlund K, Wallin U, Påhlman L, Kultima HG, Mayrhofer M, Micke P, Isaksson A, Botling J, Glimelius B, Sundström M (2015) Microsatellite instability and mutations in BRAF and KRAS are significant predictors of disseminated disease in colon cancer. BMC Cancer 15:125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1144-x

Brenner BM, Swede H, Jones BA, Anderson GR, Stoler DL (2012) Genomic instability measured by inter-(simple sequence repeat) PCR and high-resolution microsatellite instability are prognostic of colorectal carcinoma survival after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol 19(1):344–350. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-1708-1

Carethers JM, Smith EJ, Behling CA, Nguyen L, Tajima A, Doctolero RT, Cabrera BL, Goel A, Arnold CA, Miyai K, Boland CR (2004) Use of 5-fluorouracil and survival in patients with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 126(2):394–401

Chang SC, Lin JK, Yang SH, Wang HS, Li AF, Chi CW (2006) Relationship between genetic alterations and prognosis in sporadic colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer J Intl Cancer 118(7):1721–1727. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.21563

Chang EY, Dorsey PB, Johnson N, Lee R, Walts D, Johnson W, Anadiotis G, Kiser K, Frankhouse J (2006) A prospective analysis of microsatellite instability as a molecular marker in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg 191(5):646–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.02.015

Chouhan H, Sammour T, M LT, J WM (2019) Prognostic significance of BRAF mutation alone and in combination with microsatellite instability in stage III colon cancer. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol 15(1):69–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.13096

Curran B, Lenehan K, Mulcahy H, Tighe O, Bennett MA, Kay EW, O’Donoghue DP, Leader M, Croke DT (2000) Replication error phenotype, clinicopathological variables, and patient outcome in Dukes’ B stage II (T3,N0,M0) colorectal cancer. Gut 46(2):200–204

Des Guetz G, Lecaille C, Mariani P, Bennamoun M, Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Boisseau A, Sastre X, Cucherousset J, Lagorce C, Schischmanoff PO, Morere JF (2010) Prognostic impact of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer patients treated with adjuvant FOLFOX. Anticancer Res 30(10):4297–4301

Deschoolmeester V, Van Damme N, Baay M, Claes K, Van Marck E, Baert FJ, Wuyts W, Cabooter M, Weyler J, Vermeulen P, Lardon F, Vermorken JB, Peeters M (2008) Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon carcinomas has no independent prognostic value in a Belgian study population. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 44(15):2288–2295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.043

de Weger VA, Turksma AW, Voorham QJ, Euler Z, Bril H, van den Eertwegh AJ, Bloemena E, Pinedo HM, Vermorken JB, van Tinteren H, Meijer GA, Hooijberg E (2012) Clinical effects of adjuvant active specific immunotherapy differ between patients with microsatellite-stable and microsatellite-instable colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res 18(3):882–889. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-1716

Diep CB, Thorstensen L, Meling GI, Skovlund E, Rognum TO, Lothe RA (2003) Genetic tumor markers with prognostic impact in Dukes’ stages B and C colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 21(5):820–829

Donada M, Bonin S, Nardon E, De Pellegrin A, Decorti G, Stanta G (2011) Thymidilate synthase expression predicts longer survival in patients with stage II colon cancer treated with 5-flurouracil independently of microsatellite instability. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 137(2):201–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-010-0872-1

Drucker A, Arnason T, Yan SR, Aljawad M, Thompson K, Huang WY (2013) Ephrin b2 receptor and microsatellite status in lymph node-positive colon cancer survival. Transl Oncol 6(5):520–527

Du C, Zhao J, Xue W, Dou F, Gu J (2013) Prognostic value of microsatellite instability in sporadic locally advanced rectal cancer following neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Histopathology 62(5):723–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.12069

Elsaleh H, Cserni G, Iacopetta B (2002) Extent of nodal involvement in stage III colorectal carcinoma: relationship to clinicopathologic variables and genetic alterations. Dis Colon Rectum 45(9):1218–1222. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.dcr.0000027039.89662.33

Emterling A, Wallin A, Arbman G, Sun XF (2004) Clinicopathological significance of microsatellite instability and mutated RIZ in colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 15(2):242–246

Eveno C, Lefevre JH, Svrcek M, Bennis M, Chafai N, Tiret E, Parc Y (2014) Oncologic results after multivisceral resection of clinical T4 tumors. Surgery 156(3):669–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2014.03.040

Ferri M, Lorenzon L, Onelli MR, La Torre M, Mercantini P, Virgilio E, Balducci G, Ruco L, Ziparo V, Pilozzi E (2013) Lymph node ratio is a stronger prognostic factor than microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer patients: results from a 7 years follow-up study. Int J Surg (London, England) 11(9):1016–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.05.031

Fujiyoshi K, Yamamoto G, Takenoya T, Takahashi A, Arai Y, Yamada M, Kakuta M, Yamaguchi K, Akagi Y, Nishimura Y, Sakamoto H, Akagi K (2017) Metastatic pattern of stage IV colorectal Cancer with high-frequency microsatellite instability as a prognostic factor. Anticancer Res 37(1):239–247. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.11313

Gafa R, Maestri I, Matteuzzi M, Santini A, Ferretti S, Cavazzini L, Lanza G (2000) Sporadic colorectal adenocarcinomas with high-frequency microsatellite instability. Cancer 89(10):2025–2037

Gavin PG, Colangelo LH, Fumagalli D, Tanaka N, Remillard MY, Yothers G, Kim C, Taniyama Y, Kim SI, Choi HJ, Blackmon NL, Lipchik C, Petrelli NJ, O’Connell MJ, Wolmark N, Paik S, Pogue-Geile KL (2012) Mutation profiling and microsatellite instability in stage II and III colon cancer: an assessment of their prognostic and oxaliplatin predictive value. Clin Cancer Res 18(23):6531–6541. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-0605

Gervaz P, Cerottini JP, Bouzourene H, Hahnloser D, Doan CL, Benhattar J, Chaubert P, Secic M, Gillet M, Carethers JM (2002) Comparison of microsatellite instability and chromosomal instability in predicting survival of patients with T3N0 colorectal cancer. Surgery 131(2):190–197

Ghanipour L, Jirström K, Sundström M, Glimelius B, Birgisson H (2017) Associations of defect mismatch repair genes with prognosis and heredity in sporadic colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 43(2):311–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2016.10.013

Gkekas I, Novotny J, Fabian P, Nemecek R, Palmqvist R, Strigard K, Pecen L, Svoboda T, Gurlich R, Gunnarsson U (2019) Deficient mismatch repair as a prognostic marker in stage II colon cancer patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 45(10):1854–1861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2019.05.023

Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, Aronson MD, Holowaty EJ, Bull SB, Redston M, Gallinger S (2000) Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 342(2):69–77. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200001133420201

Guidoboni M, Gafa R, Viel A, Doglioni C, Russo A, Santini A, Del Tin L, Macri E, Lanza G, Boiocchi M, Dolcetti R (2001) Microsatellite instability and high content of activated cytotoxic lymphocytes identify colon cancer patients with a favorable prognosis. Am J Pathol 159(1):297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61695-1

Gupta S, Ashfaq R, Kapur P, Afonso BB, Nguyen TP, Ansari F, Boland CR, Goel A, Rockey DC (2010) Microsatellite instability among individuals of Hispanic origin with colorectal cancer. Cancer 116(21):4965–4972. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25486

Hartman DJ, Nikiforova MN, Chang DT, Chu E, Bahary N, Brand RE, Zureikat AH, Zeh HJ, Choudry H, Pai RK (2013) Signet ring cell colorectal carcinoma: a distinct subset of mucin-poor microsatellite-stable signet ring cell carcinoma associated with dismal prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol 37(7):969–977. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182851e2b

Hemminki A, Mecklin JP, Jarvinen H, Aaltonen LA, Joensuu H (2000) Microsatellite instability is a favorable prognostic indicator in patients with colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy. Gastroenterology 119(4):921–928

Hong SP, Min BS, Kim TI, Cheon JH, Kim NK, Kim H, Kim WH (2012) The differential impact of microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and tumour response between colon cancer and rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 48(8):1235–1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.10.005

Hu J, Yan WY, Xie L, Cheng L, Yang M, Li L, Shi J, Liu BR, Qian XP (2016) Coexistence of MSI with KRAS mutation is associated with worse prognosis in colorectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 95(50):e5649. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000005649

Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, Magill L, Beaumont C, Stahlschmidt J, Richman S, Chambers P, Seymour M, Kerr D, Gray R, Quirke P (2011) Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 29(10):1261–1270. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.30.1366

Hveem TS, Merok MA, Pretorius ME, Novelli M, Baevre MS, Sjo OH, Clinch N, Liestol K, Svindland A, Lothe RA, Nesbakken A, Danielsen HE (2014) Prognostic impact of genomic instability in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 110(8):2159–2164. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.133

Imai Y (2015) Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the colon: subsite location and clinicopathologic features. Int J Color Dis 30(2):187–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-2070-0

Iachetta F, Domati F, Reggiani-Bonetti L, Barresi V, Magnani G, Marcheselli L, Cirilli C, Pedroni M (2016) Prognostic relevance of microsatellite instability in pT3N0M0 colon cancer: a population-based study. Intern Emerg Med 11(1):41–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-015-1285-6

Jensen SA, Vainer B, Kruhoffer M, Sorensen JB (2009) Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer and association with thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase expression. BMC Cancer 9:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-9-25

Johannsdottir JT, Bergthorsson JT, Gretarsdottir S, Kristjansson AK, Ragnarsson G, Jonasson JG, Egilsson V, Ingvarsson S (1999) Replication error in colorectal carcinoma: association with loss of heterozygosity at mismatch repair loci and clinicopathological variables. Anticancer Res 19(3a):1821–1826

Jover R, Zapater P, Castells A, Llor X, Andreu M, Cubiella J, Balaguer F, Sempere L, Xicola RM, Bujanda L, Rene JM, Clofent J, Bessa X, Morillas JD, Nicolas-Perez D, Pons E, Paya A, Alenda C (2009) The efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer depends on the mismatch repair status. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 45(3):365–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.016

Jung SH, Kim SH, Kim JH (2016) Prognostic impact of microsatellite instability in colorectal Cancer presenting with mucinous, signet-ring, and poorly differentiated cells. Ann Coloproctol 32(2):58–65. https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2016.32.2.58

Kakar S, Aksoy S, Burgart LJ, Smyrk TC (2004) Mucinous carcinoma of the colon: correlation of loss of mismatch repair enzymes with clinicopathologic features and survival. Mod Pathol 17(6):696–700. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800093

Kalady MF, Dejulius KL, Sanchez JA, Jarrar A, Liu X, Manilich E, Skacel M, Church JM (2012) BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with distinct clinical characteristics and worse prognosis. Dis Colon Rectum 55(2):128–133. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823c08b3

Kang J, Lee HW, Kim IK, Kim NK, Sohn SK, Lee KY (2015) Clinical implications of microsatellite instability in T1 colorectal cancer. Yonsei Med J 56(1):175–181. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2015.56.1.175

Kang BW, Kim JG, Lee SJ, Chae YS, Moon JH, Sohn SK, Jeon SW, Jung MK, Lim KH, Jang YS, Park JS, Jun SH, Choi GS (2011) Clinical significance of microsatellite instability for stage II or III colorectal cancer following adjuvant therapy with doxifluridine. Med Oncol (Northwood, London, England) 28(Suppl 1):S214–S218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-010-9701-2

Kevans D, Wang LM, Sheahan K, Hyland J, O’Donoghue D, Mulcahy H, O’Sullivan J (2011) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) protein expression in a cohort of stage II colorectal cancer patients with characterized tumor budding and mismatch repair protein status. Int J Surg Pathol 19(6):751–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896911414566

Kim JE, Hong YS, Kim HJ, Kim KP, Kim SY, Lim SB, Park IJ, Kim CW, Yoon YS, Yu CS, Kim JC, Kim JH, Kim TW (2017) Microsatellite instability was not associated with survival in stage III colon cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy of oxaliplatin and infusional 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFOX). Ann Surg Oncol 24(5):1289–1294. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5682-5

Kim CG, Ahn JB, Jung M, Beom SH, Kim C, Kim JH, Heo SJ, Park HS, Kim JH, Kim NK, Min BS, Kim H, Koom WS, Shin SJ (2016) Effects of microsatellite instability on recurrence patterns and outcomes in colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer 115(1):25–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.161

Kim JE, Hong YS, Kim HJ, Kim KP, Lee JL, Park SJ, Lim SB, Park IJ, Kim CW, Yoon YS, Yu CS, Kim JC, Hoon KJ, Kim TW (2015) Defective mismatch repair status was not associated with DFS and OS in stage II Colon Cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 22(Suppl 3):S630–S637. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4807-6

Kim ST, Lee J, Park SH, Park JO, Lim HY, Kang WK, Kim JY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Rhee PL, Kim DS, Yun H, Cho YB, Kim HC, Yun SH, Lee WY, Chun HK, Park YS (2010) Clinical impact of microsatellite instability in colon cancer following adjuvant FOLFOX therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 66(4):659–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-009-1206-3

Kim GP, Colangelo LH, Wieand HS, Paik S, Kirsch IR, Wolmark N, Allegra CJ (2007) Prognostic and predictive roles of high-degree microsatellite instability in colon cancer: a National Cancer Institute-National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Collaborative Study. J Clin Oncol 25(7):767–772. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2006.05.8172

Kim SH, Shin SJ, Lee KY, Kim H, Kim TI, Kang DR, Hur H, Min BS, Kim NK, Chung HC, Roh JK, Ahn JB (2013) Prognostic value of mucinous histology depends on microsatellite instability status in patients with stage III colon cancer treated with adjuvant FOLFOX chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol 20(11):3407–3413. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3169-1

Kim JE, Hong YS, Ryu MH, Lee JL, Chang HM, Lim SB, Kim JH, Jang SJ, Kim MJ, Yu CS, Kang YK, Kim JC, Kim TW (2011) Association between deficient mismatch repair system and efficacy to irinotecan-containing chemotherapy in metastatic colon cancer. Cancer Sci 102(9):1706–1711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02009.x

Klingbiel D, Saridaki Z, Roth AD, Bosman FT, Delorenzi M, Tejpar S (2015) Prognosis of stage II and III colon cancer treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil or FOLFIRI in relation to microsatellite status: results of the PETACC-3 trial. Ann Oncol 26(1):126–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu499

Korphaisarn K, Pongpaibul A, Limwongse C, Roothumnong E, Klaisuban W, Nimmannit A, Jinawath A, Akewanlop C (2015) Deficient DNA mismatch repair is associated with favorable prognosis in Thai patients with sporadic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 21(3):926–934. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.926

Lanza G, Gafa R, Maestri I, Santini A, Matteuzzi M, Cavazzini L (2002) Immunohistochemical pattern of MLH1/MSH2 expression is related to clinical and pathological features in colorectal adenocarcinomas with microsatellite instability. Mod Pathol 15(7):741–749. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mp.0000018979.68686.b2

Lanza G, Gafa R, Santini A, Maestri I, Guerzoni L, Cavazzini L (2006) Immunohistochemical test for MLH1 and MSH2 expression predicts clinical outcome in stage II and III colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 24(15):2359–2367. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2005.03.2433

Lee SY, Kim DW, Lee HS, Ihn MH, Oh HK, Min BS, Kim WR, Huh JW, Yun JA, Lee KY, Kim NK, Lee WY, Kim HC, Kang SB (2015) Low-level microsatellite instability as a potential prognostic factor in sporadic colorectal cancer. Medicine 94(50):e2260. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000002260

Li P, Xiao ZT, Braciak TA, Ou QJ, Chen G, Oduncu FS (2017) Impact of age and mismatch repair status on survival in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med 6(5):975–981. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1007

Liang JT, Huang KC, Lai HS, Lee PH, Cheng YM, Hsu HC, Cheng AL, Hsu CH, Yeh KH, Wang SM, Tang C, Chang KJ (2002) High-frequency microsatellite instability predicts better chemosensitivity to high-dose 5-fluorouracil plus leucovorin chemotherapy for stage IV sporadic colorectal cancer after palliative bowel resection. Int J Cancer J Intl Cancer 101(6):519–525. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.10643

Lim SB, Jeong SY, Lee MR, Ku JL, Shin YK, Kim WH, Park JG (2004) Prognostic significance of microsatellite instability in sporadic colorectal cancer. Int J Color Dis 19(6):533–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-004-0596-2

Lin CC, Lin JK, Lin TC, Chen WS, Yang SH, Wang HS, Lan YT, Jiang JK, Yang MH, Chang SC (2014) The prognostic role of microsatellite instability, codon-specific KRAS, and BRAF mutations in colon cancer. J Surg Oncol 110(4):451–457. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23675

Lin CC, Lai YL, Lin TC, Chen WS, Jiang JK, Yang SH, Wang HS, Lan YT, Liang WY, Hsu HM, Lin JK, Chang SC (2012) Clinicopathologic features and prognostic analysis of MSI-high colon cancer. Int J Color Dis 27(3):277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-011-1341-2

Maccaroni E, Bracci R, Giampieri R, Bianchi F, Belvederesi L, Brugiati C, Pagliaretta S, Del Prete M, Scartozzi M, Cascinu S (2015) Prognostic impact of mismatch repair genes germline defects in colorectal cancer patients: are all mutations equal? Oncotarget 6(36):38737–38748. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5395

MacQuarrie E, Arnason T, Gruchy J, Yan S, Drucker A, Huang WY (2012) Microsatellite instability status does not predict total lymph node or negative lymph node retrieval in stage III colon cancer. Hum Pathol 43(8):1258–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2011.10.002

Maestro ML, Vidaurreta M, Sanz-Casla MT, Rafael S, Veganzones S, Martinez A, Aguilera C, Herranz MD, Cerdan J, Arroyo M (2007) Role of the BRAF mutations in the microsatellite instability genetic pathway in sporadic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 14(3):1229–1236. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-006-9111-z

Markovic S, Antic J, Dragicevic N, Hamelin R, Krivokapic Z (2012) High-frequency microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation (V600E) in unselected Serbian patients with colorectal cancer. J Mol Histol 43(2):137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10735-011-9387-6

Meng WJ, Sun XF, Tian C, Wang L, Yu YY, Zhou B, Gu J, Xia QJ, Li Y, Wang R, Zheng XL, Zhou ZG (2007) Microsatellite instability did not predict individual survival in sporadic stage II and III rectal cancer patients. Oncology 72(1-2):82–88. https://doi.org/10.1159/000111107

Merok MA, Ahlquist T, Royrvik EC, Tufteland KF, Hektoen M, Sjo OH, Mala T, Svindland A, Lothe RA, Nesbakken A (2013) Microsatellite instability has a positive prognostic impact on stage II colorectal cancer after complete resection: results from a large, consecutive Norwegian series. Ann Oncol 24(5):1274–1282. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds614

Messerini L, Ciantelli M, Baglioni S, Palomba A, Zampi G, Papi L (1999) Prognostic significance of microsatellite instability in sporadic mucinous colorectal cancers. Hum Pathol 30(6):629–634

Mohan HM, Ryan E, Balasubramanian I, Kennelly R, Geraghty R, Sclafani F, Fennelly D, McDermott R, Ryan EJ, O'Donoghue D, Hyland JM, Martin ST, O'Connell PR, Gibbons D, Winter D, Sheahan K (2016) Microsatellite instability is associated with reduced disease specific survival in stage III colon cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 42(11):1680–1686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2016.05.013

Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Kashfi SM, Mirtalebi H, Taleghani MY, Azimzadeh P, Savabkar S, Pourhoseingholi MA, Jalaeikhoo H, Asadzadeh Aghdaei H, Kuppen PJ, Zali MR (2016) Low level of microsatellite instability correlates with poor clinical prognosis in stage II colorectal Cancer patients. J Oncol 2016:2196703. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2196703

Mouradov D, Domingo E, Gibbs P, Jorissen RN, Li S, Soo PY, Lipton L, Desai J, Danielsen HE, Oukrif D, Novelli M, Yau C, Holmes CC, Jones IT, McLaughlin S, Molloy P, Hawkins NJ, Ward R, Midgely R, Kerr D, Tomlinson IP, Sieber OM (2013) Survival in stage II/III colorectal cancer is independently predicted by chromosomal and microsatellite instability, but not by specific driver mutations. Am J Gastroenterol 108(11):1785–1793. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.292

Nakaji Y, Oki E, Nakanishi R, Ando K, Sugiyama M, Nakashima Y, Yamashita N, Saeki H, Oda Y, Maehara Y (2017) Prognostic value of BRAF V600E mutation and microsatellite instability in Japanese patients with sporadic colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 143(1):151–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-016-2275-4

Nash GM, Gimbel M, Cohen AM, Zeng ZS, Ndubuisi MI, Nathanson DR, Ott J, Barany F, Paty PB (2010) KRAS mutation and microsatellite instability: two genetic markers of early tumor development that influence the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 17(2):416–424. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0713-0

Nehls O, Hass HG, Okech T, Zenner S, Hsieh CJ, Sarbia M, Borchard F, Gruenagel HH, Gaco V, Porschen R, Gregor M, Klump B (2009) Prognostic implications of BAX protein expression and microsatellite instability in all non-metastatic stages of primary colon cancer treated by surgery alone. Int J Color Dis 24(6):655–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-009-0635-0

Nopel-Dunnebacke S, Schulmann K, Reinacher-Schick A, Porschen R, Schmiegel W, Tannapfel A, Graeven U (2014) Prognostic value of microsatellite instability and p53 expression in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. Z Gastroenterol 52(12):1394–1401. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1366781

Nordholm-Carstensen A, Krarup PM, Morton D, Harling H (2015) Mismatch repair status and synchronous metastases in colorectal cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Cancer J Intl Cancer 137(9):2139–2148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29585

Ogino S, Nosho K, Kirkner GJ, Kawasaki T, Meyerhardt JA, Loda M, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS (2009) CpG island methylator phenotype, microsatellite instability, BRAF mutation and clinical outcome in colon cancer. Gut 58(1):90–96. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2008.155473

Oh SY, Kim do Y, Kim YB, Suh KW (2013) Oncologic outcomes after adjuvant chemotherapy using FOLFOX in MSI-H sporadic stage III colon cancer. World J Surg 37(10):2497–2503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2120-8

Ohrling K, Edler D, Hallstrom M, Ragnhammar P (2010) Mismatch repair protein expression is an independent prognostic factor in sporadic colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden) 49(6):797–804. https://doi.org/10.3109/02841861003705786

Ooki A, Akagi K, Yatsuoka T, Asayama M, Hara H, Takahashi A, Kakuta M, Nishimura Y, Yamaguchi K (2014) Combined microsatellite instability and BRAF gene status as biomarkers for adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 110(8):982–988. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23755

Parc Y, Gueroult S, Mourra N, Serfaty L, Flejou JF, Tiret E, Parc R (2004) Prognostic significance of microsatellite instability determined by immunohistochemical staining of MSH2 and MLH1 in sporadic T3N0M0 colon cancer. Gut 53(3):371–375

Park JW, Chang HJ, Park S, Kim BC, Kim DY, Baek JY, Kim SY, Oh JH, Choi HS, Park SC, Jeong SY (2010) Absence of hMLH1 or hMSH2 expression as a stage-dependent prognostic factor in sporadic colorectal cancers. Ann Surg Oncol 17(11):2839–2846. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-1135-8

Phipps AI, Lindor NM, Jenkins MA, Baron JA, Win AK, Gallinger S, Gryfe R, Newcomb PA (2013) Colon and rectal cancer survival by tumor location and microsatellite instability: the Colon Cancer Family Registry. Dis Colon Rectum 56(8):937–944. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828f9a57

Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, Thibodeau SN, French AJ, Goldberg RM, Hamilton SR, Laurent-Puig P, Gryfe R, Shepherd LE, Tu D, Redston M, Gallinger S (2003) Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 349(3):247–257. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa022289

Rosty C, Williamson EJ, Clendenning M, Walters RJ, Win AK, Jenkins MA, Hopper JL, Winship IM, Southey MC, Giles GG, English DR, Buchanan DD (2014) Should the grading of colorectal adenocarcinoma include microsatellite instability status? Hum Pathol 45(10):2077–2084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2014.06.020

Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D, Dietrich D, Biesmans B, Bodoky G, Barone C, Aranda E, Nordlinger B, Cisar L, Labianca R, Cunningham D, Van Cutsem E, Bosman F (2010) Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol 28(3):466–474. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2009.23.3452

Salahshor S, Kressner U, Fischer H, Lindmark G, Glimelius B, Pahlman L, Lindblom A (1999) Microsatellite instability in sporadic colorectal cancer is not an independent prognostic factor. Br J Cancer 81(2):190–193. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6690676

Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Wolff RK, Tripp SR, Caan BJ, Slattery ML (2009) Microsatellite instability and survival in rectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 20(9):1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9410-3

Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Ma KN, Schaffer D, Coleman LW, Leppert M, Slattery ML (2001) Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon cancer is associated with an improved prognosis at the population level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 10(9):917–923

Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, Labianca R, Hamilton SR, French AJ, Kabat B, Foster NR, Torri V, Ribic C, Grothey A, Moore M, Zaniboni A, Seitz JF, Sinicrope F, Gallinger S (2010) Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(20):3219–3226. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2009.27.1825

Saridaki Z, Papadatos-Pastos D, Tzardi M, Mavroudis D, Bairaktari E, Arvanity H, Stathopoulos E, Georgoulias V, Souglakos J (2010) BRAF mutations, microsatellite instability status and cyclin D1 expression predict metastatic colorectal patients’ outcome. Br J Cancer 102(12):1762–1768. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605694

Shima K, Morikawa T, Yamauchi M, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Liao X, Meyerhardt JA, Fuchs CS, Ogino S (2011) TGFBR2 and BAX mononucleotide tract mutations, microsatellite instability, and prognosis in 1072 colorectal cancers. PLoS One 6(9):e25062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025062

Shin US, Cho SS, Moon SM, Park SH, Jee SH, Jung EJ, Hwang DY (2014) Is microsatellite instability really a good prognostic factor of colorectal cancer? Ann Coloproctol 30(1):28–34. https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2014.30.1.28

Sinicrope FA, Shi Q, Smyrk TC, Thibodeau SN, Dienstmann R, Guinney J, Bot BM, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Goldberg RM, Mahoney M, Sargent DJ, Alberts SR (2015) Molecular markers identify subtypes of stage III colon cancer associated with patient outcomes. Gastroenterology 148(1):88–99. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.041

Sinicrope FA, Mahoney MR, Smyrk TC, Thibodeau SN, Warren RS, Bertagnolli MM, Nelson GD, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Alberts SR (2013) Prognostic impact of deficient DNA mismatch repair in patients with stage III colon cancer from a randomized trial of FOLFOX-based adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 31(29):3664–3672. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.48.9591

Sinicrope FA, Rego RL, Halling KC, Foster N, Sargent DJ, La Plant B, French AJ, Laurie JA, Goldberg RM, Thibodeau SN, Witzig TE (2006) Prognostic impact of microsatellite instability and DNA ploidy in human colon carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology 131(3):729–737. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.005

Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Thibodeau SN, Marsoni S, Monges G, Labianca R, Kim GP, Yothers G, Allegra C, Moore MJ, Gallinger S, Sargent DJ (2011) DNA mismatch repair status and colon cancer recurrence and survival in clinical trials of 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 103(11):863–875. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djr153

Slik K, Kurki S, Korpela T, Carpen O, Korkeila E, Sundstrom J (2017) Ezrin expression combined with MSI status in prognostication of stage II colorectal cancer. PLoS One 12(9):e0185436. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185436

Srdjan M, Jadranka A, Ivan D, Branimir Z, Daniela B, Petar S, Velimir M, Zoran K (2016) Microsatellite instability & survival in patients with stage II/III colorectal carcinoma. Indian J Med Res 143(Supplement):S104–s111. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-5916.191801

Sun Z, Yu X, Wang H, Zhang S, Zhao Z, Xu R (2014) Clinical significance of mismatch repair gene expression in sporadic colorectal cancer. Exp Ther Med 8(5):1416–1422. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2014.1927

Taieb J, Zaanan A, Le Malicot K, Julie C, Blons H, Mineur L, Bennouna J, Tabernero J, Mini E, Folprecht G, Van Laethem JL, Lepage C, Emile JF, Laurent-Puig P (2016) Prognostic effect of BRAF and KRAS mutations in patients with stage III colon cancer treated with leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin with or without cetuximab: a post hoc analysis of the PETACC-8 trial. JAMA Oncol 2(5):643–653. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5225

Tan WJ, Hamzah JL, Acharyya S, Foo FJ, Lim KH, Tan IBH, Tang CL, Chew MH (2018) Evaluation of long-term outcomes of microsatellite instability status in an Asian cohort of sporadic colorectal cancers. J Gastrointest Cancer 49(3):311–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-017-9953-6

Thomas ML, Hewett PJ, Ruszkiewicz AR, Moore JW (2015) Clinicopathological predictors of benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy for stage C colorectal cancer: Microsatellite unstable cases benefit. Asia-Pac J Clin Oncol 11(4):343–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.12411

Tian S, Roepman P, Popovici V, Michaut M, Majewski I, Salazar R, Santos C, Rosenberg R, Nitsche U, Mesker WE, Bruin S, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Bernards R, Simon I (2012) A robust genomic signature for the detection of colorectal cancer patients with microsatellite instability phenotype and high mutation frequency. J Pathol 228(4):586–595. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4092

Tikidzhieva A, Benner A, Michel S, Formentini A, Link KH, Dippold W, von Knebel DM, Kornmann M, Kloor M (2012) Microsatellite instability and Beta2-Microglobulin mutations as prognostic markers in colon cancer: results of the FOGT-4 trial. Br J Cancer 106(6):1239–1245. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.53

Toon CW, Chou A, DeSilva K, Chan J, Patterson J, Clarkson A, Sioson L, Jankova L, Gill AJ (2014) BRAFV600E immunohistochemistry in conjunction with mismatch repair status predicts survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol 27(5):644–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.200

Touchefeu Y, Provost-Dewitte M, Lecomte T, Morel A, Valo I, Mosnier JF, Bossard C, Eugene J, Duchalais E, Chetritt J, Guyetant S, Bezieau S, Senellart H, Caulet M, Cauchin E, Matysiak-Budnik T (2016) Clinical, histological, and molecular risk factors for cancer recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28(12):1394–1399. https://doi.org/10.1097/meg.0000000000000725

Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, Gibbs P, Jiang ZQ, Lieu CH, Agarwal A, Maru DM, Sieber O, Desai J (2011) Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 117(20):4623–4632. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26086

Turner N, Wong HL, Templeton A, Tripathy S, Whiti Rogers T, Croxford M, Jones I, Sinnathamby M, Desai J, Tie J, Bae S, Christie M, Gibbs P, Tran B (2016) Analysis of local chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate combined with systemic inflammation improves prognostication in stage II colon cancer independent of standard clinicopathologic criteria. Int J Cancer J Intl Cancer 138(3):671–678. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29805