Abstract

Background

Constipation causes a large number of medical visits each year and imposes significant financial toll on healthcare systems worldwide. So the present community-based study was conducted in order to estimate attributable direct and indirect costs to functional constipation (FC) and to provide an overview of related physician visits in general population of Iran.

Methods

From May 2006 to December 2007, a total of 19,200 adult persons (aged 16 and above) were drawn randomly in Tehran province, Iran (response rate 94%). Participants who reported any gastrointestinal symptoms (2,790 persons) were referred to assigned physicians to be questioned about symptoms of functional bowel disorders according to the Rome III criteria. Direct and indirect costs to FC were calculated. Attributable costs were reported as purchasing power parity dollars (PPP$).

Results

Of the total 18,180 consenting participants in this study, 435 (2.4%) had FC according to Rome III criteria. Mean total cost of constipation per person was 146.84 PPP$, of which 128.68 PPP$ was related to direct costs and 18.16 PPP$ to indirect costs. Higher educated persons (189.75 PPP$), those above 64 years of age (373.42 PPP$), subjects with BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2 (510.84 PPP$), and widowed persons (258.50 PPP$) had the highest costs.

Conclusions

This study determined that although the economic burden of FC does not seem to be substantial in comparison to other major health problems, it still exacts a substantial toll on the health system for two reasons: chronicity and ambiguity of symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Constipation is a common gastrointestinal symptom that affects 2–28% of the population, depending on demographic factors, sampling, and definition [1, 2]. Functional constipation (FC) is a functional bowel disorder (FBD) with persistently difficult, infrequent, or seemingly incomplete defecation that does not meet irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) criteria [3]. In an Iranian study, Adibi et al. [4] reported the overall prevalence of self-reported constipation to be 9.6% among adults attending a premarriage health screening and consultation center, although 32.9% of these individuals met the Rome II criteria for FC.

The symptoms associated with constipation are often intermittent and mild; however, they may be chronic, difficult to treat, and debilitating [5]. Constipation is a common problem that causes a large number of medical visits and generates important healthcare costs as a result of the diagnostic procedures involved, associated medical problems, and treatment with laxatives and herbal remedies [6, 7]. Moreover, it may require colectomy in severe and disabling cases [7].

Approximately one-third of patients with constipation seek healthcare [1]. In the USA, it leads to more than 2.5 million physicians visits, 92,000 hospitalizations, and laxative sales of several hundred million dollars a year [8, 9]. Constipation not only cause higher health care utilization but also interfere with patients’ work and productivity.

Roshandel et al. [10] studied the medical consultation and cost of different types of FBD in an outpatient gastroenterology clinic in central Tehran from December 2004 to May 2005. The direct costs for consulters and non-consulters were US$57.23 and US$1.04, respectively. Indirect costs of FC for consulters and non-consulters were US$587.48 and US$97.49, respectively.

To our knowledge, there are no published data on the cost analysis of FC in general population in Iran. Given the importance of determination of economic burden of various diseases in resource allocation and policy making, this study was conducted to determine direct costs, to estimate indirect costs, and to evaluate medical visits related to FC in an Iranian general population.

Methods

This community-based study was carried out in Tehran province, Iran, from May 2006 to December 2007. Out of the 10,000,000 residents of this area, 19,200 adult persons (aged 16 and above) were randomly selected (by cluster sampling according to national postal code) from five urban areas of the province that were under health jurisdiction of Shahid Beheshti University (M.C.) including Damavand, Firouzkouh, Varamin, Pakdasht, and northern districts of city of Tehran, of which 18,180 persons gave their consent to be finally interviewed (response rate 94%).

The sampled population was interviewed by trained healthcare workers at their own residence area. Informed consent was taken from all participants, and anonymity was warranted. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University (M.C.).

Data regarding gender, age, weight, height, and level of education were recorded from every participant in the first place. In addition, participants were informed and asked about 11 gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms including abdominal pain/discomfort, constipation, diarrhea, bloating, heartburn/acid regurgitation, proctalgia, nausea/vomiting, fecal incontinence, bloody or black stool (melena), anorexia/weight loss, and difficulty of swallowing.

Participants who reported any of the above symptoms (2,790 persons) were referred to assigned physicians in the vicinity to be questioned about symptoms of FBDs according to the Rome III criteria [3]. The assigned physicians would use a standardized Persian questionnaire that contained 40 questions about GI symptoms on the basis of Rome III criteria. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this questionnaire was tested in a pilot study on 400 participants from the city of Damavand. For validity study, language, content, concurrence, and construct validities were examined. The test–retest reliability was good and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values were above 0.7 for all of major symptoms included in the tool. Small interpretation corrections, however, were made regarding some minor symptoms so as to enhance intelligibility and to decrease ambiguity of questions [11].

Subjects with the following criteria for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to interview were considered to have diagnosis of FC [3]:

-

1.

two or more of the following:

-

(a)

Straining during at least 25% of defecations

-

(b)

Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25% of defecations

-

(c)

Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25% of defecations

-

(d)

Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for at least 25% of defecations

-

(e)

Manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25% of defecations (e.g., digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor)

-

(f)

Fewer than three defecations per week

-

(a)

-

2.

Sparsity of soft stool in absence of laxative use

-

3.

Symptoms do not fulfill IBS criteria

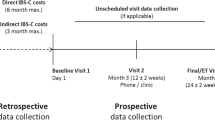

A second questionnaire was designed to depict an overview of direct (medical visits, hospitalizations, laboratory tests, imaging studies, and medications) and indirect costs (productivity loss) attributable to FC. This questionnaire was filled out for patients with documented FC [11].

Productivity loss was estimated as the number of the days in which constipation symptoms had impeded patient’s routine daily activities or had caused at least 30% of functionality loss in daily activities without causing disability. In this respect, the patients were asked about their absence from work in the last 6 months and the number of days with low functionality (at least 30% loss of function) in their job or daily activities because of constipation symptoms.

The unit costs of health resources, including medical visits, were calculated based on the price lists approved by Iranian official health authorities [12]. In case of laboratory tests, patients were simply asked about the type of the laboratory samples or specimens they had given previously; the reason was that we assumed it could be the best remembered point about a laboratory test to a patient. Therefore, patients only had to determine whether they had blood, urine, or stool tests for a certain number of times asked by a physician for workup of FBD-related symptoms. Then the minimum cost of a blood test was assumed equal to the cost of a complete blood count (CBC) test, because it is the most common and cheapest tests ordered by a physician. Similarly, the minimum costs of a urinalysis and a stool exam were considered for a urine or stool test, respectively.

The prices of chemical drugs were also abstracted from the website of Food and Drug Organization of Iran (2005, published in Farsi, http://www.irteb.com). When considering the cost of herbal and chemical drugs, if different brands were available, the cheapest brand was taken into account. As most of the patients could not recall the exact dosage of drugs they had used, we considered the lowest acceptable dosage for adults and the minimum acceptable duration of medical therapies, unless the patient exactly knew how long he or she had taken the drug.

In addition, although herbals in this report are meant to include both herbal drugs and herbs having therapeutic effects, we only included the herbal drugs in cost analysis. We defined herbal drugs as those existing as registered herbal drugs in Iranian pharmacopoeia, a list of which was published in Persian [13]. The authors could not find the cost of herbal drugs listed in Iranian pharmacopoeia in any hardcopy or electronic publication. Therefore, the authors contacted the corresponding manufacturers to get the price of the herbal drugs.

To estimate attributable indirect cost to productivity loss, the days of total activity loss were summed up. Three days with low functionality (see definition above) were considered as 1 day of total activity loss. Then the average total activity loss for each patient was estimated in a year’s period.

All costs were converted to purchasing power parity dollars (PPP$) to facilitate cross-country comparison of costs. Iranian gross national income (GNI) per capita (in 2007) in US$ and PPP$ was retrieved from the World Bank website. The average daily income of each Iranian was assumed to be 1/365 of GNI per capita.

The rate of unemployment (11%, reported by the World Bank Organization) was applied. US dollar was assumed to be in an average rate of 9,171 Iranian Rials based on reports from the Central Bank of Iran in 2006. Comparing 2006 GNI per capita in US dollars (US$3,470) and PPP$ (10,800 PPP$) from the World Bank database (and the exchange rate of US$1=9,171 Iranian Rials), we arrived at the estimation of 1 PPP$ to be 2,878 Iranian Rials. This was then used to convert costs from Iranian Rials to PPP$. Using PPP$ is preferred to the US$ based on usual exchange rates and makes cross-country comparison of costs more reliable.

Chi-square test was used for detecting significant differences in the frequencies of utilization of different health resources between the two groups of patients. Mann–Whitney U test was employed to compare the means of continuous data with nonparametric distribution. P values below 0.05 will be considered significant.

Results

Of the 18,180 persons who participated in this study, 459 (2.5%) had FC according to Rome III criteria. Constipated patients with complete date (435) were entered in the analysis. Mean age (±standard deviation) of patients with FC was 47.26 ± 15.83. 184 (42.3%) patients aged more than 50 years. Female-to-male ratio was 2.71. Majority of patients (75.2%) were married, 12% were widowed, 10.8% were single, and 2% were divorced. Mean body mass index (BMI) of patients was 26.53 ± 4.69 kg/m2.

A number of 265 (60.9%) patients had been visited at least once by physician for FC; 61.9% of men and 59% of women had sought medical consultation. Subjects with age above 64 years consulted more often than other age groups (P = 0.03). Medical consultation for FC was observed mostly in patients with lower education levels (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference between different BMI groups regarding physician visits.

There was no significant symptoms oriented variation regarding rate of seeking heathcare facilities. In addition, data indicated that people who had sought medical attention more frequently would use herbal medications to a larger extent (P = 0.02). According to the multivariate study, after entering sex, age groups, BMI groups, educational groups, and marital status, a higher educational level (diploma and high educated) were associated with less seeking medical consultation (odds ratio 0.53, 95% CI 0.34–0.80, P = 0.003; Table 1).

Table 2 presents frequency of healthcare utilization and productivity loss among patients with FC. A number of 340 patients (78.2%) had medical visits, mainly by general practitioners, for constipation complaint, and only 28 (6.4%) needed hospital admission for further work-up. Chemical drugs were more frequently used than herbal drugs (48.5% vs. 7.6%). An overwhelming majority of patients (91.5%) had not experienced days off work for symptoms of FC.

Mean total cost of constipation per person was 146.84 PPP$, of which 128.68 PPP$ was for direct costs and 18.16 PPP$ for indirect costs. Hospitalization and physician visit costs accounted for highest attributable costs, respectively (Table 3).

Table 4 represents costs of FC per person according to demographic status. Mean cost of FC was higher in women than men (149.09 PPP$ vs. 140.68 PPP$). Higher education, older age, lower BMI, and widowed status corresponded to higher amounts of expenditure.

Discussion

The aim of this population-based study was to give an estimation of the economic burden of FC. In this respect, the diagnosis was confirmed by using Rome III criteria. Moreover, direct and indirect costs were taken into account to depict an accurate picture of the financial burden of this entity of functional gastrointestinal disorders.

While majority of previous Iranian studies in this regard have evaluated volunteers recruited from certain populations or specific ethnic groups, in the present study, cluster sampling was employed on a random basis to reduce the selection bias. For the first time in Iran, the present study aspired to depict an overview of the attributable direct and indirect costs to FC in general population; however, like other studies contending with functional GI disorders, this study faced a major obstacle: recall bias. Moreover, we employed Rome III criteria to determine patients with FC.

Few studies have applied this set of criteria up until now; therefore, we will have to compare our findings mainly to studies that have used Rome II criteria. As Rome III criteria should be fulfilled for the last 3 months, in contrast with Rome II criteria which should be for much longer period (6 months), it seems that Rome III criteria is more sensitive than Rome II criteria [14]

Our findings demonstrated a general prevalence of 2.5% for FC. While the rate of physician consultation was about 78.2% among FC patients and 56% of these patients had consumed drugs, the rate of due hospitalization was only 6.4%. Accordingly, the mean total expenditure was calculated to be 146.84 PPP$ per patient for FC. Given the relatively high prevalence of constipation complaints (either functional or not) in Iranian society [4] and the relatively high per patient costs, it is implied that the clinical and financial importance of constipation disorders has not been fully addressed in previous reports [15]. In other words, it has been underestimated.

In our study, 2.4% of the study population had FC, whereas in a study on selected people aged between 14 and 41 years, 22.9% of individuals met the Rome II criteria for FC [4]. The lower estimation of prevalence of FC in the present study might be because our study population mainly comprised small cities, suburbs, and rural places, and symptoms could be underestimated by patients in these areas and complicated questions could still be confusing and prone to misinterpretation [16].

As it was expected, seeking medical consultation for FC was so frequent (60.9%) due to chronicity and bothersome nature of constipation. However, certain groups of patients, including patients older than 64 years, lower educational level, and herbal drug users, sought medical consultation more frequently. Aging is associated with progressive deterioration of anatomy, biology, and physiology of human beings. The incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates of organic lower gastrointestinal disease increase with age and gastrointestinal problems in the elderly form a significant proportion of hospital and general practice workload [17].

Education level is not a known risk factor for constipation [18], and it is not evident how it may affect the rate of seeking medical attention. One of the scarce studies that have tried to address this issue has depicted a direct association between educational level and seeking medical care [19], which is in contrast to our findings. A probable explanation for this difference is accessibility of different brands of over-the-counter drugs in high socioeconomic areas of the country. In contrast, according to an Iranian patient, in referral system in rural areas and primary care centers, which are more probable to be of lower socioeconomic status, most drugs are only available via physicians’ prescription, which is far cheaper than areas like the city.

In our study, using chemical drugs was more frequent than herbal drugs. We found that 78.2% of patients had medical visits. So the higher proportion of the consumption of chemical drugs can easily be attributed to the higher prescriptions of these drugs by corresponding physicians. These findings were compatible with a study on the referral patients visited in a private clinic [10].

An overwhelming majority of patients (91.5%) had not experienced days off work for symptoms of FC. This is compatible with a pioneer study in Iran, in which 92.2% and 96.9% of consulters and non-consulters had never gone off-work because of FC [20]. Although FC is a chronic and bothersome disease, its symptoms are, in general, tolerable by patients and not very severe [20], so that most patients with constipation will make better with at least lifestyle interventions [7]. So we did not expect a great deal of disability in the setting of FC, and low rate of off-work days was completely expected in this setting.

According to our estimation, direct costs, including hospitalization and physician visits, constituted the largest proportion of economic burden of FC by a mean of 128.68 PPP$ per person. Despite the lower rate of hospitalization, its related costs were estimated to be 64.18 PPP$, while physician visits imposed a toll of 34.40 PPP$ per person.

A recent study [10], from the very center that conducted the present one, on the referral of GI patients to a specialized clinic estimated a mean total cost of about 743 PPP$ per person for FC, of which about 685 PPP$ belonged to indirect costs and just 58 PPP$ were related to direct costs. The disproportion presented in the results of this study with ours mainly arises from the different settings in which these researches were undertaken. Majority of patients in the aforementioned study were chronic patients who had decided to seek medical solutions in places other than their original medical facilities. Moreover, as the reader may notice, the difference of estimated costs is much dramatic in terms of indirect costs, which in the case of frustrated patients of Roshandel’s study may most probably have comprised transportation costs (journey to clinics in larger cities), accommodation (e.g., hotels), more off-work days, decreased functionality: in other words, the cumulative productivity loss and accessory expenditures.

In the present study, the mean cost of FC was estimated as “per person per 6 months.” Given the estimated prevalence of FC, the general population of Iran (71 × 106 persons) [21] and the duration of this study, the total annual cost was calculated to be 500.43 × 106 PPP$ accordingly, of which 438.54 × 106 PPP$ was attributable to direct costs and 61.89 × 106 PPP$ belonged to indirect costs.

As mentioned earlier, the estimated economic burden of FC in the present study could have been underestimated because of several factors including variability of symptom severity, recall bios, and implementation of the least possible national costs for each category of medications. This means that the real economic burden of FC is more than the estimation of this study. Therefore, resource allocation for FBDs and institution of research programs regarding early intervention and diagnosis of FBDs should be reconsidered by policy makers and health authorities.

FBDs have significant impact in health economics of different populations. According to a report from the National Institutes of Health [22], the total cost of gastrointestinal diseases in the USA exceeded US$141 billion in year 2004, of which direct costs comprised US$97.8 billion. On other hand, the total direct cost of healthcare expenditure for all diseases in the USA in 2004 was estimated to be US$1.9 trillion [21]. In a study by Nyrop et al. [23], mean total annual costs for healthcare provision through Group Health Cooperative (claims data) were US$5049 (CI US$4,441–5,667) for IBS, US$6140 (CI US$5,070–7,151) for diarrhea, US$7,522 (CI US$5.689–9.146) for constipation, and US$7646 (CI US$6,458–8,736) for abdominal pain.

Although there was no significant difference between male and female patients in the present study, mean cost of FC was more in women than men (149.09 vs. 140.68 PPP$). Highly educated persons (189.75 PPP$), patients above 64 years of age (373.42 PPP$), subjects with BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2 (510.84 PPP$), and widowed persons (258.50 PPP$) had the highest costs. As it is seen in Table 1, women and patients with BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 sought medical visits more frequently that was followed by clinical and paraclinical studies. So it can explain the larger total cost in these groups.

Our study determined that direct costs comprise the largest part of economic burden of FC; however, indirect cost are yet to be addressed in future studies because, as mentioned earlier, the studies that depict a precise overview of this matter are scarce. Moreover, this study determined that although the economic burden of FC does not seem substantial in comparison to other major health problems, it still exacts a substantial toll on the health system for two reasons: chronicity and ambiguity of symptoms. Given the bothersome nature of FC and the experience of this study, we highly recommend the inclusion of quality-of-life measurements in the future studies on FC and FBDs, in general.

References

Talley N (2004) Definitions, epidemiology, and impact of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 4(Suppl 2):S3–S10

Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson W, Irvine E, Rance L (2001) An epidemiological survey of constipation in Canada: definitions, rates, demographics and predictors of health care. Am J Gastroenterol 96:3131–3137

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC (2006) Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 130:1480–1491

Adibi P, Behzad E, Pirzadeh S, Mohseni M (2007) Bowel habit reference values and abnormalities in young Iranian healthy adults. Dig Dis Sci 52(8):1810–1813

Lembo A, Camilleri M (2003) Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 349(14):1360–1368

Tedesco F, DiPiro J (1985) Laxative use in constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 80:303–309

Rantis PC Jr, Vernava AM 3rd, Daniel GL, Longo WE (1997) Chronic constipation—is the work-up worth the cost? Dis Colon Rectum 40(3):280–286

Sonnenberg A, Koch T (1989) Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci 34:606–611

Johanson J, Sonnenberg A, Koch T (1989) Clinical epidemiology of chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol 11:525–536

Roshandel D, Rezailashkajani M, Shafaee S, Zali MR (2007) A cost analysis of functional bowel disorders in Iran. Int J Colorectal Dis 22(7):791–799

Khoshkrood-Mansoori B, Pourhoseingholi MA, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Sedigh-Tonekaboni B, Pourhoseingholi A, Habibi M, Zali MR (2009) Irritable bowel syndrome: a population based study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 18(4):413–418

Comprehensive database of Iranian physicians. Available from http://www.irteb.com/fee.htm

Database of herbal drugs in Iran. Available from: http://www.irteb.com/herbal/herbaldrugeindex.htm

Comparison table of Rome II & Rome III adult diagnostic criteria. Available from: http://www.romecriteria.org/assets/pdf/20_RomeIII_apB_899–916.pdf

Khoshbaten M, Hekmatdoost A, Ghasemi H, Entezariasl M (2004) Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and signs in northwestern Tabriz, Iran. Indian J Gastroenterol 23(5):168–170

Anastasiou F, Mouzas I, Moschandreas J, Kouroumalis E, Lionis C (2008) Exploring the agreement between diagnostic criteria for IBS in primary care in Greece. BMC Res Notes 1:127

Lederle FA (1995) Epidemiology of constipation in elderly patients. Drug utilisation and cost-containment strategies. Drugs Aging 6(6):465–469

Chang J, Locke G, Schleck C, Zinsmeister A, Talley N (2007) Risk factors for chronic constipation and a possible role of analgesics. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19(11):905–911

Gálvez C, Garrigues V, Ortiz V, Ponce M, Nos P, Ponce J (2006) Healthcare seeking for constipation: a population-based survey in the Mediterranean area of Spain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 24(2):421–428

Talley N (2008) Functional gastrointestinal disorders as a public health problem. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20(S1):121–129

Data catalog. The World Bank. http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/DATASTATISTICS/0,,contentMDK:20535285~menuPK:1390200~pagePK:64133150~piPK:64133175~theSitePK:239419,00.html

Everhart JE (ed) (2008) The burden of digestive diseases in the United States. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Nyrop K, Palsson O, Levy R, Korff M, Feld A, Turner M et al (2007) Costs of healthcare for irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, functional diarrhoea and functional abdominal pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 26(2):237–248

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohaghegh Shalmani, H., Soori, H., Khoshkrood Mansoori, B. et al. Direct and indirect medical costs of functional constipation: a population-based study. Int J Colorectal Dis 26, 515–522 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-1077-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-1077-4