Abstract

Subject

Anal incontinence is a well-known and feared complication following surgery involving the anal sphincter, particularly if partial transection of the sphincter is part of the surgical procedure.

Methods

The literature was reviewed to evaluate the risk of postoperative incontinence following anal dilatation, lateral sphincterotomy, surgery for haemorrhoidal disease and anal fistula.

Results

Various degrees of anal incontinence are reported with frequencies as follows: anal dilatation 0–50%, lateral sphincterotomy 0–45%, haemorrhoidal surgery 0–28%, lay open technique of anal fistula 0–64% and plastic repair of fistula 0–43%. Results vary considerably depending on what definition of “incontinence” was applied. The most important risk factors for postoperative incontinence are female sex, advanced age, previous anorectal interventions, childbirth and type of anal surgery (sphincter division). Sphincter lesions have been reported following procedures as minimal as exploration of the anal canal via speculum.

Conclusions

Continence disorders after anal surgery are not uncommon and the result of the additive effect of various factors. Certain risk factors should be considered before choosing the operative procedure. Since options for surgical repair of postoperative incontinence disorders are limited, careful indications and minimal trauma to the anal sphincter are mandatory in anal surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most proctological disorders may be treated conservatively; however, some cases require surgery to achieve long-term resolution of symptoms. Although surgical therapy of haemorrhoids and anal fissure has a higher long-term probability of success as compared to conservative methods, the risk of complications increases according to the extent of surgical intervention. Likewise, operations of anal fistula carry a high risk of postoperative incontinence especially if parts of the anal sphincter are transected. This review focuses on the risk of incontinence reported in the literature following certain anal operations.

Anatomic and functional aspects

Control of defaecation involves a complex interaction of various factors. Besides the two sphincters, “motoric” continence is supported by the muscular system of the pelvic floor and the haemorrhoidal plexus as well as ligaments, fasciae and organs of pelvis minor. According to Lestar et al. [1] 27% of the resting pressure of the anal canal is due to the voluntary action and 53% to the involuntary action of the external and internal anal sphincters, respectively. The remaining 20% are maintained by the haemorrhoidal plexus. Important factors for “sensory” continence include sensitive anoderm and rectal reservoir and neurological and psychological factors. Incontinence may be caused by a disturbed interaction of the two components. Therefore, incontinence may result from sphincter lesions, loss of sensitive anoderm and loss of reservoir (rectosigmoid resection, reduced rectal compliance due to keloid formation and inflammations).

Although often very difficult, a detailed determination of the predominant dysfunction is an essential prerequisite for the right therapy. Besides the involuntary passage of gas, liquid or solid faeces (incontinence level I–III according to Parks [2]), continued soiling or urge incontinence may considerably compromise the quality of life. In addition, consistence of faeces and the subjective level of impairment are of predominant importance. The assessment of personal impairment in relation to objective medical findings represents a problem in the evaluation of incontinence. The degree of sphincter dysfunction does not always correlate with the patient’s subjective awareness of his functional deficit.

In order to evaluate the potential effect anal surgery may have on continence, a detailed preoperative history is mandatory. Subjective and objective functional impairment of continence should be assessed by inquiring, e.g. the frequency of involuntary passage of gas, liquid or solid faeces. This may be complemented with an incontinence score (e.g. Wexner-Score [3]). In addition, the correct perception of stool consistence (solid–semisolid–liquid–changing) is important. As the clinical classification of incontinence is very difficult, in this paper, “continence disorder” is defined as subjective sensation of functional impairment due to uncontrolled defaecation.

Women in particular should be interviewed about previous anorectal surgery as well as the obstetric history since vaginal childbirth is an important risk factor for incontinence. Endosonographic imaging has revealed sphincter defects in up to 30% of women following childbirth [4, 5]. Sphincter defects may therefore be an important contributor to continence disorders [6].

Even simple exploration of the anal canal via speculum may cause sphincter lesions. Van Tets and Kuijpers [7] compared haemorrhoidal surgery with and without use of a Park’s retractor and found an 8% decrease of resting pressure without and 20% with use of the retractor, respectively. Similarly, Ho et al. [8] compared stapled haemorrhoidopexy with and without speculum and endosonographically detected lesions of the internal sphincter in four patients (n = 29) after 14 weeks. However, this caused no faecal incontinence. In another trial on surgical anastomosis, Ho et al. [9] compared biofragmentable ring to transanal stapled anastomosis. In this series, three of 18 patients suffered from symptoms of incontinence level III caused by exploration of the anal canal. Lesions of the internal sphincter were detected endosonographically in five patients while two patients showed lesions of the external sphincter. Weyand et al. [10] reported a significant manometric decrease of the resting pressure during stapled haemorrhoidopexy. The decrease was higher when an anal speculum was applied as compared to a vaginal speculum. These publications support the view that simple nonsurgical anal and transanal manipulation may traumatise the sphincter, which may have long-term sequelae.

All these factors may contribute to varying degrees to the outcome of anorectal surgery. We therefore reviewed the literature to collect and summarise the effects of various anal operations on continence.

Anal dilatation

Anal dilatation by insertion of a speculum to expose the anal canal, which is an integral part of most anorectal surgical procedures, may cause continence disorders due to minor sphincter trauma which is mostly temporary. The retractor should therefore be inserted carefully and the time of exploration should be as short as possible.

Digital anal dilatation according to Lord (Table 1) for the treatment of chronic anal fissure is associated with a high incidence of continence disorders of up to 27% according to a meta-analysis of Nelson [11]. Internal sphincter lesions were detected endosonographically in 76% of patients; 24% were found to even have tears of the external sphincter [12]. After anal dilatation, up to 50% of all patients suffer from continence disorders. It is nowadays widely accepted that the Lord procedure may be regarded as obsolete.

Lateral sphincterotomy–fissurectomy

Therapy of anal fissure is primarily conservative. Recently introduced new substances like local injection of botulinum toxin, topical glyceryl trinitrate and diltiazem enhance the chances of successful healing of acute anal fissures [13–16].

After failure of conservative therapy, fissurectomy without transection of parts of the internal anal sphincter and lateral sphincterotomy compete as operation of choice. Lateral transection of the internal sphincter leads to high healing rates by reduction of the increased sphincter tone [17]. However, sphincterotomy is also associated with a high rate of continence disorders of up to 35% (Table 1) [18, 19]. Hasse et al. [20] analysed long-term results after lateral sphincterotomy in 209 patients (Table 2). While the healing rate amounted to 95%, he observed an incontinence rate of 15% (level I and II) 3 months after operation. This rate increased to 21% (mainly level II and III) in the further course. Good healing rates and relatively high rates of continence disorders are also confirmed by other authors [11]. It is therefore a matter of controversy whether this method still represents the treatment of choice for chronic anal fissure [17].

Systematic reports on incontinence after fissurectomy are sparse. Meier zu Eissen [21] observed faecal spotting in 3.1% of 470 treated patients. Engel [22] observed no incontinence after fissurectomy and local application of isosorbide dinitrate (mean follow-up 29 months). Low rates of continence disorders are reported after fissurectomy in combination with botulinum toxin: Lindsey et al. [23] observed 7% of transient flatus incontinence (mean follow-up 16 weeks) and Scholz et al. [24] observed one mild incontinence 6 weeks after surgery (n = 40). A recent publication reports one case of urge incontinence for more than 18 months (n = 46) [25]. Sileri et al. [26] found no continence disorders, although there was a lower healing rate in the fissurectomy–botulinum toxin group as compared to lateral sphincterotomy. All this continence disorders may be a transient result of the botulinum toxin.

According to Garcia-Aguilar et al. [19], the danger of continence disorder corresponds to the length of internal sphincterotomy and depends on the thickness of the external sphincter. However, incomplete internus sphincterotomy is related to a significantly higher rate of fissure recurrence [27].

Haemorrhoidal surgery

Surgery should only be the last step in the algorithm of treatment of haemorrhoidal disorders [28]. Continence disorders following haemorrhoidal surgery are reported to vary between 0% and 28% (Tables 3 and 4) and depend on the extent of haemorrhoidal protrusion (previous lesions), operative method and surgical expertise [29, 30]. Besides the obligatory excision of sensitive anoderm, accidental lesions of the internal sphincter as well as keloid formation combined with functional impairment of rectal compliance may play an important role. The clinical relevance of each of these factors is very variable. Furthermore, asymptomatic findings are very common. Following stapled haemorrhoidopexy, the most frequent impairment is urge incontinence which is mainly due to the shortening of the anal canal and the removal of sensitive anoderm as a consequence of placing the staple line too deep towards the anal canal [30, 31]. By applying the correct surgical technique, the risk of incontinence is the same in all procedures. However, postoperative continence disorders often disappear spontaneously after wound healing [32].

Sphincter lesions following conventional haemorrhoidal surgery are often detected endosonographically. After the Milligan–Morgan procedure, internal sphincter lesions were found in 5.5% of 123 patients by Stamatiadis et al. [12] but, as expected, no external sphincter lesion was found. Felt-Bersma et al. [33] reported sphincter defects with incontinence in two of 24 patients and a defect without incontinence in one more patient 31 months after haemorrhoidal surgery. Abbasakor et al. [34] diagnosed continence disorders in ten of 16 patients and endosonographically revealed a sphincter defect in eight cases.

Anal fistula

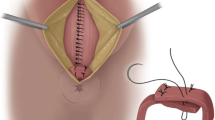

In contrast to the above-mentioned anal diseases, there are more clearly defined surgical indications for anal fistula. While an abscess in general requires an urgent intervention, the cure of the persisting fistula aims at preventing a recurrent septic process, which may lead to further destruction of parts of the anal sphincter and may potentially be life threatening. Anal fistulas are therefore a clear indication for an operation, and surgical intervention should be offered to every patient. Nevertheless, surgery of anal fistula is a major reason for continence disorders due to surgical trauma as transection of considerable parts of the sphincter musculature is usually part of the operation. This explains the high rates (18–64%) of continence disorders reported following the lay open method of anal fistulae (Table 5). A wide range of incontinence rates (0–42%) are reported following plastic reconstructive methods (Table 6) without any obvious difference between the various plastic methods employed (mucosa–submucosa flap, rectal advancement flap and anoderm lobes) [35].

The variability of results is mainly due to different definitions of “incontinence” applied, the morphological diversity of fistulae and previous operations. The rate of continence disorder found positively correlates with the precise clinical recording. Thus, by use of a score, Cavanaugh et al. [36] reported the highest rate of incontinence disorders following fistulotomy (64%).

Repeat operations which by their own right may all cause sphincter lesions are not uncommon due to the complexity and recurrent nature of some anal fistula. Zimmermann et al.[37] found preoperative continence disorders in 52% of patients. The high variability of continence rates in several trials may therefore be explained by the heterogeneity of cases involved with various types of fistulae (types II and III according to Parks, recto-vaginal fistulae), fistula due to chronic inflammatory bowel diseases and different numbers of previous operations [35].

Unsurprisingly, the severity of incontinence depends directly on the thickness of transection of muscular tissue. Garcia-Aguilar et al. [38] found continence disorders in patients following fistula surgery in 38% when the external sphincter was left intact. The increase of transection of the external sphincter resulted in a direct increase of the incontinence rate: <25%:44%, 26–50%:60%, 51–75%:55% and >75%:75%, respectively. In 70% of his patients with transsphincteric fistulae, Cavanaugh et al. [36] found an involvement of the external sphincter of less than 25%, in only 6% was the involvement more than 50%. This underlines the importance of a precise intraoperative localisation of the fistula to avoid unnecessary damage to the external sphincter.

Stamatiadis et al. [12] endosonographically detected internal sphincter lesions in 57% and external sphincter lesions in 29% of patients following plastic repair of their fistula. Interestingly, 62% and 75% of the patients with lesions of the internus and externus, respectively, did not report any incontinence. The rate of damage to the internus increased to 75% and to the externus to 30% after more than two anorectal operations. Twenty-six per cent of the patients reported a continence disorder. Manometric studies revealed a significant decrease of anal pressure after anal fistula surgery. As early as 1983, Belliveau et al. [39] described a significant decrease of manometric values after laying open of intersphincteric and transsphincteric anal fistulae with corresponding continence disorders. In this context, the shortening of the anal canal, which is more pronounced after laying open of transsphincteric as compared to intersphincteric fistula, plays an important role [40]. In a recent trial, Gustafsson and Graf [41] showed a decrease of manometric values 3 months after fistula operations including plastic operative methods. Values may decrease even more after 12 months.

Risk factors for a continence disorder after fistula surgery are female sex, age of >50 years, high (transsphincteric) anal fistula, type of anal surgery and previous operations [38]. Decisions on operative procedure should take these factors into consideration.

Alternative methods like application of fibrin glue do not cause any noticeable functional impairment of faecal continence. However, the very inconsistent healing rates of 14–81% require further evaluation [42–45]. At present, there are no long-term results on anal fistula plug as a new “minimally invasive” method [46, 47].

Discussion

Postoperative incontinence disorders as sequel of anal surgery are sizeable and relevant problems each surgical proctologist is confronted with from time to time. A proportion of patients showing manometric and endosonographic changes following anal surgery remain asymptomatic [12, 33, 39]. However, in combination with identified or unidentified previous lesions, these findings may add up to cause clinically relevant continence disorders. Most important risk factors for incontinence among women older than 40 years are as follows: overweight, chronic obstructive lung disease, irritable bowel syndrome, urinary incontinence and partial resection of the colon [48].

A high variability of incidence of continence disorders are reported in the literature. Rates vary between 0% and 50% for anal dilatations, up to 45% for lateral sphincterotomy, 0–64% for lay open of anal fistula, up to 20% for haemorrhoidal surgery and 0–28% for stapled haemorrhoidopexy. The crucial problem in this context is the diverging definition of the term “incontinence”. At present, there is still no unanimously accepted definition and mode of evaluation of “faecal incontinence”. The assessment of continence disorder varies accordingly in the literature. The Parks classification is applied most commonly which simply stratifies the inability to control gas, liquid and solid stool [49]. However, this simple classification describes continence disorders only incompletely. The classification of incontinence by means of a special score [3, 50] often fails because of the large number of examinations needed for a long follow-up. Another problem is the great number of different scores published. For scientific publication, however, the application of one widely accepted score would be desirable.

Besides the history, clinical examination plays an important role as well. Thus, perianal eczema or perianal faecal soiling may be signs for higher-grade incontinence, even if the patient does not report any problems. This often occurs in patients who communicate their medical condition insufficiently. Nevertheless, the patient’s subjective awareness of his continence disorder is an important factor and needs to be considered before suggesting a therapy.

Besides recurrence, faecal incontinence is the most important factor for postoperative satisfaction following the treatment of anal fistulae [51]. A rate of third-grade incontinence of up to 10%, as reported by Stelzner et al. in 1956 [52], would not be acceptable today. Quality-of-life indices may possibly be a useful adjunct for the analysis of this problem [53, 54].

Patients presenting with continence disorders require a thorough proctological examination including manometry and endosonography of the anal sphincter to differentiate the disorder [55, 56]. Optimal treatment depends on the evaluation of all facts including previous lesions and the individual situation of the patient.

One of the earliest publications on postoperative incontinence was presented in 1975 by Blum and Akovbiantz [57]. Besides conservative treatment by means of biofeedback and bulking agents, secondary surgical reconstruction to treat postoperative incontinence is suggested only for healthy and strong sphincters. Other options are the mechanical reinforcement of the sphincter (Thiersch-Ring) or later sphincter replacement. However, over the course of time, these procedures have not produced convincing results.

As stated above, postoperative incontinence may be the result of a variable combination of sphincter defects, loss of anoderm and keloid formation. A precise differentiation of the underlying disorder is prerequisite to symptom-orientated treatment.

Bulking agents, electrostimulation and biofeedback therapy are primary treatment options [58]. Operative options are often limited and usually aim at reconstruction of the sphincter integrity. Direct suturing of the internal sphincter has brought only modest results in terms of re-establishing continence. While Morgan et al. [59] did not observe any improvement among 13 patients, Abou Zeid [60] reported improved continence in eight patients. Following the repair, Leroi et al. [61] endosonographically demonstrated persistent internus defects in five patients despite of subjective improvement.

More satisfactory short-term results with a rate of 79% completely continent patients have been reported following the reconstruction of isolated sphincter defects after anal surgery [62]. Following sphincter repair, Kammer-Doak et al. [63] found no correlation between endosonographic integrity of the sphincter and the actual grade of incontinence. In his series, four of ten patients regained complete continence and a further four patients reported considerable improvement. Results of sphincter repair are less encouraging among women with obstetric trauma, women older than 50 years and patients with a descending perineum [64]. Overall, in most series, the procedure is initially successful in about 40–50% of patients but results tend to deteriorate over the time [65]. Thus, reported long-term results of sphincter reconstruction are quite sobering.

More extensive surgical procedures like dynamic graciloplasty or artificial bowel sphincter should be reserved for individual cases due to their highly invasive character and associated costs. Sacral nerve stimulation normally requires an intact anal sphincter [66], yet improvement has been reported even in patients with sphincter defects [67–69].

Therapeutic options to improve postoperative incontinence are limited. In cases of mild disorders (soiling, urge incontinence), which may considerably impair the quality of life, conservative measures (electrostimulation, biofeedback) are usually very time-consuming for the patient. Operative procedures may achieve satisfactory results for a limited proportion of patients only.

Summary and conclusion

Impairment of anal continence following anal surgery represents a relevant problem. Sphincter lesions are common; however, only in rare instances does this lead to clinically relevant continence disorders. Data on continence disorders vary to a high degree and may be confounded by patients with unidentified or even identified previous lesions, temporary improvement and the subjectivity of perception of incontinence. Another serious problem is the diversity of definitions for the term “incontinence”.

Awareness of the potentially deleterious effect of anal surgery, optimal protection of the anal sphincter and the sensitive anoderm, as well as a critical indication is the best-possible prophylaxis to reduce postoperative continence disorders. This is particularly important since the impact of conservative as well as surgical procedures to re-establish continence is limited.

References

Lestar B, Penninckx F, Kerremans R (1989) The composition of anal basal pressure—an in vivo and in vitro study in man. Int J Colorect Dis 4:118–122

Parks AG (1975) Royal society of medicine, section of proctology; meeting 27 November 1974. president's address. Anorectal incontinence. Proc R Soc Med 68:681–690

Jorge JM, Wexner SD (1993) Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 36:77–97

Sultan AH, Michael CB, Kamm A, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI (1993) Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. New Engl J Med 329:1905–1911

Fitzpatrick M, Fynes M, Cassidy M, Behan M, O'Connell PR, O'Herlihy C (2000) Prospective study of the influence of parity and operative technique on the outcome of primary anal sphincter repair following obstetrical injury. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 89:159–163

Damon H, Bretones S, Henry L, Mellier G, Mion F (2005) Long-term consequences of first vaginal delivery-induced anal sphincter defect. Dis Colon Rectum 48:1772–1776

van Tets WF, Kuijpers HC (1994) Continence disorders after anal fistulotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 37:1194–1197

Ho YH, Seow-Choen F, Tsang C, Eu KW (2001) Randomized trial assessing anal sphincter injuries after stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 88:1449–1455

Ho YH, Tsang C, Tang CL, Nyam D, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F (2000) Anal sphincter injuries from stapling instruments introduced transanally: randomized, controlled study with endoanal ultrasound and anorectal manometry. Dis Colon Rectum 43:169–173

Weyand G, Webels F, Celebi H, Ommer A, Kohaus H (2002) Anale Druckverhältnisse nach Staplerhämorrhoidektomie - Eine prospektive Analyse bei 33 Patienten. Zentralbl Chir 127:22–24

Nelson RL (1999) Meta-analysis of operative techniques for fissure-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1424–1428 discussion 1428–1431

Stamatiadis A, Konstantinou E, Theodosopoulou E, Mamoura K (2002) Frequency of operative trauma to anal sphincters: evaluation with endoanal ultrasound. Gastroenterol Nurs 25:55–59

Scholefield JH, Bock JU, Marla B, Richter HJ, Athanasiadis S, Prols M, Herold A (2003) A dose finding study with 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.4% glyceryl trinitrate ointment in patients with chronic anal fissures. Gut 52:264–269

Utzig MJ, Kroesen AJ, Buhr HJ (2003) Concepts in pathogenesis and treatment of chronic anal fissure—a review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 98:968–974

Lund JN, Nystrom PO, Coremans G, Herold A, Karaitianos I, Spyrou M, Schouten WR, Sebastian AA, Pescatori M (2006) An evidence-based treatment algorithm for anal fissure. Tech Coloproctol 10:177–180

Nash GF, Kapoor K, Saeb-Parsy K, Kunanadam T, Dawson PM (2006) The long-term results of diltiazem treatment for anal fissure. Int J Clin Pract 60:1411–1413

Orsay C, Rakinic J, Perry WB, Hyman N, Buie D, Cataldo P, Newstead G, Dunn G, Rafferty J, Ellis CN, Shellito P, Gregorcyk S, Ternent C, Kilkenny J 3rd, Tjandra J, Ko C, Whiteford M, Nelson R (2004) Practice parameters for the management of anal fissures (revised). Dis Colon Rectum 47:2003–2007

Khubchandani IT, Reed JF (1989) Sequelae of internal sphincterotomy for chronic fissure in ano. Br J Surg 76:431–434

Garcia-Aguilar J, Belmonte Montes C, Perez JJ, Jensen L, Madoff RD, Wong WD (1998) Incontinence after lateral internal sphincterotomy: anatomic and functional evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum 41:423–427

Hasse C, Brune M, Bachmann S, Lorenz W, Rothmund M, Sitter H (2004) Laterale, partielle Sphinkteromyotomie zur Therapie der chronischen Analfissur - Langzeitergebnisse einer epidemiologischen Kohortenstudie. Chirurg 75:160–167

Meier zu Eissen J (2001) Chronische analfissur, therapie. Kongressbd Dtsch Ges Chir Kongr 118:654–656

Engel AF, Eijsbouts QA, Balk AG (2002) Fissurectomy and isosorbide dinitrate for chronic fissure in ano not responding to conservative treatment. Br J Surg 89:79–83

Lindsey I, Cunningham C, Jones OM, Francis C, Mortensen NJ (2004) Fissurectomy–botulinum toxin: a novel sphincter-sparing procedure for medically resistant chronic anal fissure. Dis Colon Rectum 47:1947–1952

Scholz T, Hetzer FH, Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA, Hahnloser D (2007) Long-term follow-up after combined fissurectomy and Botox injection for chronic anal fissures. Int J Colorectal Dis 22:1077–1081

Baraza W, Boereboom C, Shorthouse A, Brown S (2008) The long-term efficacy of fissurectomy and botulinum toxin injection for chronic anal fissure in females. Dis Colon Rectum 51:239–243

Sileri P, Mele A, Stolfi VM, Grande M, Sica G, Gentileschi P, Di Carlo S, Gaspari AL (2007) Medical and surgical treatment of chronic anal fissure: a prospective study. J Gastrointest Surg 11:1541–1548

Garcia-Granero E, Sanahuja A, Garcia-Armengol J, Jimenez E, Esclapez P, Minguez M, Espi A, Lopez F, Lledo S (1998) Anal endosonographic evaluation after closed lateral subcutaneous sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 41:598–601

Herold A (2007) Therapie des Hämorrhoidalleidens. Coloproctology 29:157–169

Athanasiadis S, Gandji D, Girona J (1986) Langzeitergebnisse nach submuköser Hämorrhoidektomie unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Kontinenz. Phlebol u Proktol 15:119–121

Ebert KH, Meyer HJ (2002) Die Klammernahtresektion bei Hämorrhoiden - eine Bestandsaufnahme nach zweijähriger Anwendung. Vergleich der Ergebnisse mit der Technik nach Milligan-Morgan. Zentralbl Chir 127:9–14

Ho YH, Cheong WK, Tsang C, Ho J, Eu KW, Tang CL, Seow-Choen F (2000) Stapled hemorrhoidectomy—cost and effectiveness. Randomized, controlled trial including incontinence scoring, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasound assessments at up to three months. Dis Colon Rectum 43:1666–1675

Kanellos I, Zacharakis E, Kanellos D, Pramateftakis MG, Tsachalis T, Betsis D (2006) Long-term results after stapled haemorrhoidopexy for third-degree haemorrhoids. Tech Coloproctol 10:47–49

Felt-Bersma RJ, van Baren R, Koorevaar M, Strijers RL, Cuesta MA (1995) Unsuspected sphincter defects shown by anal endosonography after anorectal surgery. A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum 38:249–253

Abbasakoor F, Nelson M, Beynon J, Patel B, Carr ND (1998) Anal endosonography in patients with anorectal symptoms after haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Surg 85:1522–1524

Köhler A, Athanasiadis S, Psarakis E (1997) Die Analfistel - Ein Plädoyer für die kontinente Fistulektomie. Coloproctology 19:186–203

Cavanaugh M, Hyman N, Osler T (2002) Fecal incontinence severity index after fistulotomy: a predictor of quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum 45:349–353

Zimmerman DDE, Briel JW, Gosselink MP, Schouten WR (2001) Anocutaneous advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 44:1474–1480

Garcia-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong WD, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD (1996) Anal fistula surgery. Factors associated with recurrence and incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 39:723–729

Belliveau P, Thomson JP, Parks AG (1983) Fistula-in-ano. A manometric study. Dis Colon Rectum 26:152–154

Lunniss PJ, Kamm MA, Phillips RK (1994) Factors affecting continence after surgery for anal fistula. Br J Surg 81:1382–1385

Gustafsson UM, Graf W (2002) Excision of anal fistula with closure of the internal opening: functional and manometric results. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1672–1678

Aitola P, Hiltunen KM, Matikainen M (1999) Fibrin glue in perianal fistulas—a pilot study. Ann Chir Gynaecol 88:136–138

Cintron JR, Park JJ, Orsay CP, Pearl RK, Nelson RL, Sone JH, Song R, Abcarian H (2000) Repair of fistulas-in-ano using fibrin adhesive: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 43:944–949 discussion 949–950

Lindsey I, Smilgin-Humphreys MM, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJ, George BD (2002) A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1608–1615

Swinscoe MT, Ventakasubramaniam AK, Jayne DG (2005) Fibrin glue for fistula-in-ano: the evidence reviewed. Tech Coloproctol 9:89–94

Champagne BJ, O'Connor LM, Ferguson M, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN (2006) Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1817–1821

Johnson EK, Gaw JU, Armstrong DN (2006) Efficacy of anal fistula plug vs. fibrin glue in closure of anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 49:371–376

Varma MG, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Beattie MS, Subak LL (2006) Fecal incontinence in females older than aged 40 years: who is at risk? Dis Colon Rectum 49:841–851

Parks AG, Porter NH, Hardcastle J (1966) The syndrome of the descending perineum. Proc Roy Soc Med 59:477–482

Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, Kane RL, Mavrantois C, Thorson AG, Wexner SD, Bliss D, Lowry AC (2000) Fecal incontinence quality of life scale—quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 43:9–17

Garcia-Aguilar J, Davey CS, Le CT, Lowry AC, Rothenberger DA (2000) Patient satisfaction after surgical treatment for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 43:1206–1212

Stelzner F, Dietl H, Hahne H (1956) Ergebnisse bei Radikaloperationen von 143 Analfisteln (Kritik der einzeitigen Sphinctertrennung bei ein- oder mehrzeitigen Fisteloperationen). Chirurg 27:158–162

Mylonakis E, Katsios C, Godevenos D, Nousias B, Kappas AM (2001) Quality of life of patients after surgical treatment of anal fistula; the role of anal manometry. Colorectal Dis 3:417–421

Mentes BB, Tezcaner T, Yilmaz U, Leventoglu S, Oguz M (2006) Results of lateral internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure with particular reference to quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1045–1051

Herold A, Bruch HP (1996) Stufendiagnostik der anorektalen Inkontinenz. Zentralbl Chir 121:632–638

Ommer A, Köhler A, Athanasiadis S (1998) Funktionsdiagnostik des Anorektums und des Beckenbodens. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 123:537–544

Blum AL, Akovbiantz A (1975) Postoperative Analinkontinenz. Internist 16:267–275

Terra MP, Dobben AC, Berghmans B, Deutekom M, Baeten CG, Janssen LW, Boeckxstaens GE, Engel AF, Felt-Bersma RJ, Slors JF, Gerhards MF, Bijnen AB, Everhardt E, Schouten WR, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J (2006) Electrical stimulation and pelvic floor muscle training with biofeedback in patients with fecal incontinence: a cohort study of 281 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1149–1159

Morgan R, Patel B, Beynon J, Carr ND (1997) Surgical management of anorectal incontinence due to internal anal sphincter deficiency. Br J Surg 84:226–230

Abou-Zeid AA (2000) Preliminary experience in management of fecal incontinence caused by internal anal sphincter injury. Dis Colon Rectum 43:198–202 discussion 202–204

Leroi AM, Kamm MA, Weber J, Denis P, Hawley PR (1997) Internal anal sphincter repair. Int J Colorectal Dis 12:243–245

Madiba TE, Moodley MM (2003) Anal sphincter reconstruction for incontinence due to non-obstetric sphincter damage. East Afr Med J 80:585–588

Kammerer-Doak DN, Dominguez C, Harner K, Dorin MH (1998) Surgical repair of fecal incontinence. Correlation of sonographic anal sphincter integrity with subjective cure. J Reprod Med 43:576–580

Nikiteas N, Korsgen S, Kumar D, Keighley MR (1996) Audit of sphincter repair. Factors associated with poor outcome. Dis Colon Rectum 39:1164–1170

Herold A (2005) Spinkterrekonstruktion/Spinkterraffung. Coloproctology 27:383–386

Ommer A (2006) Operativer schließmuskelersatz: dynamische grazilisplastik—artificial bowel sphincter—sakralnervenstimulation. Coloproctology 28:64–69

Müller C, Belyaev O, Deska T, Chromik A, Weyhe D, Uhl W (2005) Fecal incontinence: an up-to-date critical overview of surgical treatment options. Langenbecks Arch Surg 390:544–552

Holzer B, Rosen HR, Novi G, Ausch C, Holbling N, Schiessel R (2007) Sacral nerve stimulation for neurogenic faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 94:749–753

Melenhorst J, Koch SM, Uludag O, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG (2007) Sacral neuromodulation in patients with faecal incontinence: results of the first 100 permanent implantations. Colorectal Dis 9:725–730

Bachmann Nielsen M, Rasmussen OO, Pedersen JF, Christiansen J (1993) Risk of sphincter damage and anal incontinence after anal dilatation for fissure-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 36:677–680

Farouk R, Gunn J, Duthie GS (1998) Changing patterns of treatment for chronic anal fissure. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 80:194–196

Konsten J, Baeten CG (2000) Hemorrhoidectomy vs. Lord's method: 17-year follow-up of a prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum 43:503–506

Babor R, Keating JP, Isbister WH (2003) Long-term outcomes after anal dilatation for anal fissure. Coloproctology 25:135–141

Blessing H (1993) Spätergebnisse nach individueller lateraler Internus-Sphinkterotomie. Helv Chir Acta 59:603–607

Pfeifer J, Berger A, Uranus S (1994) Die chirurgische therapie der chronischen analfissur–beeinträchtigen proktologische zusatzoperationen die kontinenzleistung? Chirurg 65:630–633

Pernikoff BJ, Eisenstat TE, Rubin RJ, Oliver GC, Salvati EP (1994) Reappraisal of partial lateral internal sphincterotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 37:1291–1295

Sharp FR (1996) Patient selection and treatment modalities for chronic anal fissure. Am J Surg 171:512–515

Nyam DC, Pemberton JH (1999) Long-term results of lateral internal sphincterotomy for chronic anal fissure with particular reference to incidence of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1306–1310

Casillas S, Hull TL, Zutshi M, Trzcinski R, Bast JF, Xu M (2005) Incontinence after a lateral internal sphincterotomy: are we underestimating it? Dis Colon Rectum 48:1193–1199

Read MG, Read NW, Haynes WG, Donnelly TC, Johnson AG (1982) A prospective study of the effect of haemorrhoidectomy on sphincter function and faecal continence. Br J Surg 69:396–398

McConnell JC, Khubchandani IT (1983) Long-term follow-up of closed hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 26:797–799

Kirsch JJ, Staude G, Herold A (2001) Hämorrhoidektomie nach Longo und Milligan-Morgan - Prospektive Vergleichsstudie mit 300 Patienten. Chirurg 72:180–185

Johannsson HO, Graf W, Pahlman L (2002) Long-term results of haemorrhoidectomy. Eur J Surg 168:485–489

Hetzer FH, Demartines N, Handschin AE, Clavien PA (2002) Stapled vs excision hemorrhoidectomy: long-term results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg 137:337–340

Beattie GC, Loudon MA (2001) Follow-up confirms sustained benefit of circumferential stapled anoplasty in the management of prolapsing haemorrhoids. Br J Surg 88:850–852

Altomare DF, Rinaldi M, Sallustio PL, Martino P, De Fazio M, Memeo V (2001) Long-term effects of stapled haemorrhoidectomy on internal anal function and sensitivity. Br J Surg 88:1487–1491

Fantin AC, Hetzer FH, Christ AD, Fried M, Schwizer W (2002) Influence of stapler haemorrhoidectomy on anorectal function and on patients’ acceptance. Swiss Med Wkly 132:38–42

Jongen J, Bock JU, Peleikis HG, Eberstein A, Pfister K (2006) Complications and reoperations in stapled anopexy: learning by doing. Int J Colorectal Dis 21:166–171

Kügler S (1966) Die Kontinenz nach Spaltung anorektaler Fisteln. Chirurg 37:64–66

Akovbiantz A, Arma S, Hegglin J (1968) Kontinenz nach Sphinkterspaltung bei Analfissuren und Analfisteln. Helv Chir Acta 35:260–265

Riedler L, Papp C, Autengruber M (1978) Chirurgische Spätergebnisse bei 107 Patienten mit anorektalen Fisteln. Leber Magen Darm 8:55–58

Saino P, Husa A (1985) A prospective manometric study of the effect of anal fistula surgery on anorectal function. Acta Chir Scand 151:279–288

Westerterp M, Volkers NA, Poolman RW, van Tets WF (2003) Anal fistulotomy between Skylla and Charybdis. Colorectal Dis 5:549–551

Aguilar PS, Plasencia G, Hardy TG Jr, Hartmann RF, Stewart WR (1985) Mucosal advancement in the treatment of anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 28:496–498

Abcarian H, Dodi G, Girona J, Kronborg O, Parnaud E, Thomson JP, Vaifai M, Goligher JC (1987) Fistula-in-ano. Int J Colorectal Dis 2:51–71

Wedell J, Meier zu Eissen P, Banzhaf G, Kleine L (1987) Sliding flap advancement for the treatment of high level fistulae. Br J Surg 74:390–391

Kodner IJ, Mazor A, Shemesh EI, Fry RD, Fleshman JW, Birnbaum EH (1993) Endorectal advancement flap repair of rectovaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas. Surgery 114:682–689 discussion 689–690

Athanasiadis S, Köhler A, Nafe M (1994) Treatment of high anal fistulae by primary occlusion of the internal ostium, drainage of the intersphincteric space, and mucosal advancement flap. Int J Colorectal Dis 9:153–157

Miller GV, Finan PJ (1998) Flap advancement and core fistulectomy for complex rectal fistula. Br J Surg 85:108–110

Willis S, Rau M, Schumpelick V (2000) Chirurgische Therapie hoher anorectaler und rectovaginaler Fisteln mittels transanaler endorectaler Verschiebelappenplastik. Chirurg 71:836–840

Ortiz H, Marzo J (2000) Endorectal flap advancement repair and fistulectomy for high trans-sphincteric and suprasphincteric fistulas. Br J Surg 87:1680–1683

van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, Beets-Tan RG, Russel MG, van Gemert WG (2005) Staged mucosal advancement flap for the treatment of complex anal fistulas: pretreatment with noncutting Setons and in case of recurrent multiple abscesses a diverting stoma. Colorectal Dis 7:513–518

Perez F, Arroyo A, Serrano P, Candela F, Sanchez A, Calpena R (2005) Fistulotomy with primary sphincter reconstruction in the management of complex fistula-in-ano: prospective study of clinical and manometric results. J Am Coll Surg 200:897–903

Uribe N, Millan M, Minguez M, Ballester C, Asencio F, Sanchiz V, Esclapez P, del Castillo JR (2007) Clinical and manometric results of endorectal advancement flaps for complex anal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis 22:259–264

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ommer, A., Wenger, F.A., Rolfs, T. et al. Continence disorders after anal surgery—a relevant problem?. Int J Colorectal Dis 23, 1023–1031 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-0524-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-0524-y