Abstract

Purpose

Laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy was reported to be a safe and feasible procedure in infant with biliary atresia. We aimed to investigate the long-term results after laparoscopic portoenterostomy as such data in the literature are lacking.

Methods

Sixteen infants underwent laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy from 2002 to 2006. The age and the sex of the patient, the bilirubin level before the operation, the early clearance of jaundice (total bilirubin <20 μmol/L within 6 months of portoenterostomy), the native liver survival at 2 and 5 years after the operation were reviewed. The results were retrospectively compared with 16 consecutive infants who underwent open Kasai portoenterostomy before 2002.

Results

All infants had type III biliary atresia. The early clearance of jaundice rate at 6 months was 50 % (8/16) after laparoscopic operation and was 75 % (12/16) after open operation (p = 0.144). Two years after the operation, the native liver survival was 50 % (8/16) in the laparoscopic group and was 81 % (13/16) in the open group (p = 0.076). Five years after the operation, the native liver survival rate was 50 % (8/16) in the laparoscopic group and was 81 % (13/16) in the open group (p = 0.076). The jaundice-free native liver survival rate at 5 years was 50 % (8/16) in laparoscopic group and was 75 % (12/16) in the open group. In the laparoscopic group, all patients with early clearance of jaundice survived and remained jaundice freed 5 years after the operation.

Conclusion

The 5-year native liver survival rate after laparoscopic portoenterostomy was 50 %. Apparently superior result was observed in the open group (81 %) although the figures did not reach statistical difference because of the small sample size. A larger scale study is required to draw a more meaningful conclusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Biliary atresia is characterized by progressive inflammatory fibrosclerosing cholangiopathy. Since the introduction of portoenterostomy by Kasai in 1959, it remains the mainstay of treatment in infant with biliary atresia [1]. Recently, a review article summarized the outcome of biliary atresia after Kasai portoenterostomy in national studies. The clearance of jaundice rate ranged from 34 to 59 % and the 5-year native liver survival rate ranged from 20 to 62 % [2].

The use of laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy in the management of biliary atresia was first reported in the literature since 2002 [3]. In this 10-year period, only limited reports on laparoscopic Kasai were published [4–8]. The main focus of the reports was on the safety and feasibility of the technique. Long-term results and outcome were lacking.

Our initial experience of laparoscopic Kasai showed the early clearance of jaundice rate was 50 % [9]. A follow-up study was arranged to review the 5-year native liver survival rate and to compare the results to the infants who underwent open Kasai portoenterostomy.

Materials and methods

From 2002 to 2006, 16 consecutive infants with biliary atresia underwent laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy. The age and the sex of the patient, the bilirubin level before the operation were reviewed. The clearance of jaundice or jaundice-freed was defined as the total bilirubin <20 μmol/L. The early clearance of jaundice was defined as the total bilirubin <20 μmol/L within 6 months of portoenterostomy. The early clearance of jaundice rate, the native liver survival at 6 months, 2 years, and 5 years after the operation and the jaundice-free native liver survival at 6 months, 2 years, and 5 years after the operation were reviewed. 5-year post-operative complications including cholangitis and variceal bleeding were also studied. The results were retrospectively compared with 16 consecutive infants who underwent open portoenterostomy before 2002 in the same institute. Ethical approval was obtained from our institutional review board.

The technique of laparoscopic portoenterostomy was previously described [9]. In the open group, laparotomy was performed through a right subcostal incision. The liver was reflected outside the abdominal cavity after division of the triangular ligaments. The dissection of the fibrous cord, the fashioning of the Roux-loop and portoenterostomy were performed in similar fashion as described in the laparoscopic approach (Fig. 1). In the open group, all venous tributaries at the porta were divided between ligatures. Postoperatively, all infants in the laparoscopic group received prednisolone at 4 mg/kg started at 1 week after the operation. In the open group, there was no standardized protocol on the use of prednisolone.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was accomplished using the SPSS program for Windows 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The t test was used to compare the continuous data. Chi-square test was used to compare the categorical data. The survival curve was established according to the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 32 infants were included in this study. 16 infants underwent open Kasai portoenterostomy from 1993 to 2001. All had type III biliary atresia and were non-syndromic. The age of the infants in the open group was younger than the laparoscopic group (p < 0.01) (Table 1). The sex and the pre-operative bilirubin level in both groups were not statistically different (Table 1).

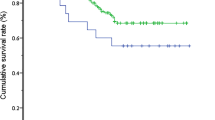

Six months after the Kasai operation, the clearance of jaundice rate in the laparoscopic group was 50 % (8/16), while the rate was 75 % (12/16) in the open group (p = 0.144). The native liver survival rate was 100 % in both groups. Two years after the operation, the native liver survival rate was 50 % (8/16) in laparoscopic group and was 81 % (13/16) in open group (p = 0.076). The jaundice-free native liver survival rate was 50 % (8/16) in laparoscopic group and was 75 % (12/16) in the open group (p = 0.144; Table 2; Fig. 2). One patient died in the laparoscopic group. He suffered from post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease after combined liver and intestine transplantation. Two patients died in the open group. One patient died because of sepsis at 8 months of age. Another patient died because of sudden infant death at 6 months of age.

Five years after the operation, the native liver survival rate was 50 % (8/16) in laparoscopic group and was 81 % (13/16) in open group (p = 0.076). The jaundice-free native liver survival rate was 50 % (8/16) in laparoscopic group and was 75 % (12/16) in open group (p = 0.144; Table 2; Fig. 2).

Within 5 years after the portoenterostomy, seven patients in laparoscopic group had cholangitis. The cholangitis were treated successfully by antibiotics in three patients and remained jaundice-free. Five patients in the open group had cholangitis and three were successfully treated. One patient in laparoscopic group had variceal bleeding 9 months after the operation. No patient in the open group had esophageal variceal bleeding with-in the study period. One patient in the laparoscopic group had volvulus of intestine and required combined liver and intestine transplantation. One patient in the open group had intestinal obstruction and required laparotomy and adhesiolysis (Table 3).

Discussions

This is the first report on the 5-year native liver survival rate after laparoscopic Kasai operation. The 5-year native liver survival rate after laparoscopic portoenterostomy in this study was 50 %. The results were comparable to other national series for patients who underwent open Kasai portoenterostomy [2]. Our studies showed patients who fail to achieve early clearance of jaundice will require liver transplantation within 2 years. However, patients who were freed of jaundice remained jaundice-free within the first 5 years.

There were few published papers reporting the outcome laparoscopic portoenterostomy in children with biliary atresia [3–8]. Because of the rarity of biliary atresia, all studies only included a small number of patients. Martinez-Ferro and Esteves series included 41 patients, which was already the study including the largest number of patient [5]. Martinez-Ferro performed 22 laparoscopic Kasai and 73 % of children had good/partial flow. Esteves performed 19 laparoscopic Kasai operations and 94.7 % had good/partial flow. The liver transplant rate at a mean of 13–14 months was 45.4 and 31 %, respectively. Ure recently reports the results of a prospective trial on laparoscopic versus conventional laparoscopic Kasai operation [10]. The laparoscopic group included 12 infants. The clearance of jaundice rate at 6 months after the operation was only 17 %. The 2-year native liver survival rate was only 8 % in laparoscopic group and was 31 % in the open group. The trial was stopped because of the inferior outcome after laparoscopic Kasai.

Although the 5-year native liver survival rate after laparoscopic Kasai operation was comparable to other national series, patients who underwent open Kasai in this institute had a better clearance of jaundice rate and 5-year native liver survival rate. Ure suggested the learning curve of laparoscopic Kasai operation may have contributed to the inferior result [10]. However, the contribution of learning curve is also applicable in open Kasai operation because of the rarity of biliary atresia. In our center, both open and laparoscopic portoenterostomy were performed by the same group of surgeons. In fact, the first four cases in the laparoscopic group had early clearance of jaundice. It is difficult to account the inferiority of the result in the laparoscopic group was solely related to the learning curve in this study.

In an animal study performed by Laje, livers with biliary atresia were highly sensitive to the detrimental effects of a prolonged pneumoperitonium [11]. It was postulated that the liver damage by pneumoperitonium may explain why the outcome of laparoscopic Kasai was less favorable. The effect of pneumoperitonium may account for the inferior native liver survival rate after laparoscopic portoenterostomy in this series.

The uses of cautery in division of the portal vein tributaries and in hemostasis at the portal plate were suggested to be the reasons for the inferior result in laparoscopic portoenterostomy [10, 12]. The technique of dissection of the fibrous cord and portoenterostomy were basically similar in the laparoscopic and the open group in this study. We minimized the use of cautery in dividing the portal vein tributaries and hemostasis as in the open approach. In the open group, the livers were reflected outside the abdominal cavity for better exposure of the portal plate. Of course, this maneuver was not applicable in the laparoscopic group. Liem reported the use of percutaneous sutures to retract the left and right hepatic arteries for better hilar exposure [8]. The limitation in portal plate exposure may also account for the inferior result in the laparoscopic group (Fig. 1).

The limitation of this study included retrospective data collection. It was generally believed that a better outcome could be achieved if early operation was performed [13]. The age of the patients in the open group was statistically younger. The timing of operation was depended on the time we received referral from the pediatrician. There is no clear reason why the age of the patients in the laparoscopic group was older. Although there was a statistically different, the mean age of the open group at operation was only 66 days. According to the reports from Nio which included more than 1,000 patients, at ages up to 90 days, there was no influence on clearance of jaundice [14]. In this study, all patients had type III biliary atresia. Davenport reported the age had no influence in isolated biliary atresia [15].

Another discrepancy was the difference in post-operative management. We followed Dillon’s protocol in the laparoscopic group [16]. All patients received prednisolone started at 4 mg/kg/day 1 week after the operation. In the open group, the use and dosage of prednisolone were not standardized because it was a historic control group. Of course, whether the use of steroid will improve the outcome after portoenterostomy was still debatable. Recent review study had showed there was no clear evidence on the use of steroid after Kasai operation [17]. The use of other adjuvant therapy including antibiotics and ursodeoxycolic acid was not standardized in the two groups. Currently, there is still no clear beneficial evidence on the beneficial effect of the adjuvant therapy [18].

Another limitation of this study is the small sample size. This truly reflected the rare incidence of biliary atresia. Because biliary atresia is a rare condition, patient care should be centralized in specialized centers. In UK, study showed the outcome was better if the center performed more than five cases per year [2]. If centralization is not practical and imperative like in Canada, Kasai operation should be performed in university-based pediatric hospital centers [19]. It was no doubt the suggestion also applied in laparoscopic Kasai operation. The complexity of the laparoscopic approach was suggested to be one of the major reasons for poorer results in published literatures [10, 12]. Laparoscopic portoenterostomy should be performed in specialized centers.

Conclusions

The 5-year native liver survival rate after laparoscopic portoenterostomy was 50 % and was comparable to the results after open operation in other studies. A higher 5-year native liver survival rate (81 %) was recorded after open portoenterostomy in our institute although it was not statistically significant. The effect of pneumoperitonium and the limited extent of portal plate exposure may account for the inferior results in the laparoscopic group.

References

Kasai M, Suzuki S (1959) A new operation for ‘‘non-correctable’’ biliary atresia: hepatic portoenterostomy. Shujjutsu 13:733

Davenport M, Ong E, Sharif K et al (2011) Biliary atresia in england and wales: results of centralization and new benchmark. J Pediatr Surg 46:1689–1694

Esteves E, Clemente Neto E, Ottaiano Neto M et al (2002) Laparoscopic kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 18:737–740

Lee H, Hirose S, Bratton B et al (2004) Initial experience with complex laparoscopic biliary surgery in children: biliary atresia and choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg 39:804–807

Martinez-Ferro M, Esteves E, Laje P (2005) Laparoscopic treatment of biliary atresia and choledochal cyst. Semin Pediatr Surg 14:206–215

Aspelund G, Ling SC, Ng V et al (2007) A role for laparoscopic approach in the treatment of biliary atresia and choledochal cysts. J Pediatr Surg 42:869–872

Dutta S, Woo R, Albanese CT (2007) Minimal access portoenterostomy: advantages and disadvantages of standard laparoscopic and robotic techniques. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 17:258–264

Liem NT, Son TN, Quynh TA et al (2010) Early outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg 45:1665–1667

Chan KW, Lee KH, Mou JW et al (2011) The outcome of laparoscopic portoenterostomy for biliary atresia in children. Pediatr Surg Int 27:671–674

Ure BM, Kuebler JF, Schukfeh N, Engelmann C et al (2011) Survival with the native liver after laparoscopic versus conventional Kasai portoenterostomy in infants with biliary atresia: a prospective trial. Ann Surg 253:826–830

Laje P, Clark FH, Friedman JR et al (2010) Increased susceptibility to liver damage from pneumoperitoneum in a murine model of biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg 45:1791–1796

Wong KK, Chung PH, Chan KL et al (2008) Should open kasai portoenterostomy be performed for biliary atresia in the era of laparoscopy? Pediatr Surg Int 24:931–933

Nio M, Ohi R, Miyano T et al (2003) Five- and 10-year survival rates after surgery for biliary atresia: a report from the japanese biliary atresia registry. J Pediatr Surg 38:997–1000

Serinet MO, Wildhaber BE, Broue P et al (2009) Impact of age at Kasai operation on its results in late childhood and adolescence: a rational basis for biliary atresia screening. Pediatrics 123:1280–1286

Davenport M, Caponcelli E, Livesey E et al (2008) Surgical outcome in biliary atresia: etiology affects the influence of age at surgery. Ann Surg 24:694–698

Dillon PW, Owings E, Cilley R et al (2001) Immunosuppression as adjuvant therapy for biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg 36:80–85

Sarkhy A, Schreiber RA, Milner RA et al (2011) Does adjuvant steroid therapy post-Kasai portoenterostomy improve outcome of biliary atresia? systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol 25:440–444

Pakarinen MP, Rintala RJ (2011) Surgery of biliary atresia. Scand J Surg 100:49–53

Schreiber RA, Barker CC, Roberts EA et al (2010) Biliary atresia in canada: the effect of centre caseload experience on outcome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 51:61–65

Conflict of interest

Drs. Kin Wai E. Chan, Kim Hung Lee, Siu Yan B. Tsui, Yuen Shan Wong, Kit Yi K. Pang, Jennifer Wai Cheung Mou, Yuk Him Tam have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, K.W.E., Lee, K.H., Tsui, S.Y.B. et al. Laparoscopic versus open Kasai portoenterostomy in infant with biliary atresia: a retrospective review on the 5-year native liver survival. Pediatr Surg Int 28, 1109–1113 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-012-3172-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-012-3172-9