Abstract

Introduction

Choroid plexus tumors are uncommon intraventricular tumors that develop from the choroid plexus of the central nervous system. Choroid plexus papillomas arising from the cerebellopontine angle have been reported to almost exclusively occur in adults and are rarely found in children.

Methods

We report a systematic review conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines of SCOPUS and PubMed databases for case reports and case series of choroid plexus papillomas arising in the cerebellopontine angle in the pediatric population and discuss clinical presentation, imaging features, management options, and outcomes. We also report a case managed at our center.

Results

Ten cases of pediatric choroid plexus papillomas arising in the cerebellopontine angle were identified from the systematic review in addition to the case reported here, resulting in a total of eleven cases. The patients’ median age was 8 years with a slight female sex predilection (1.2:1). Patients most commonly presented with headache, cerebellar signs, and cranial nerve palsies with median duration of symptoms at 4 months. All patients underwent surgical treatment with majority achieving gross total excision. No deaths were reported at median follow-up of 12 months. Complete neurologic recovery was attained in seven cases while partial recovery was seen in two cases.

Conclusion

Choroid plexus papillomas found in the cerebellopontine angle in the pediatric population are extremely rare but they should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment with excellent outcomes achievable in majority of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Choroid plexus tumors are uncommon intraventricular tumors that develop from the choroid plexus of the central nervous system [1]. They account for 0.3–0.8% of all brain tumors overall and 2–5% of all pediatric brain tumors [2, 3]. According to the World Health Organization classification of central nervous system tumors, they are classified either into choroid plexus papilloma (CPP) (WHO Grade 1), atypical choroid plexus papilloma (WHO Grade 2), or choroid plexus carcinoma (WHO Grade 3) [2]. They are frequently located in the lateral ventricles of children, while they are found more commonly at the fourth ventricles of adults [1, 2, 4, 5]. CPPs arising from the cerebellopontine angle (CPA) have been reported to almost exclusively occur in adults and are rarely found in children [1, 6, 7].

We thus performed a systematic review of the literature for case reports and case series of choroid plexus papillomas arising in the cerebellopontine angle in the pediatric population and discuss clinical presentation, imaging features, management options, and outcomes. We also report a case managed at our center.

Case report

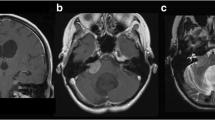

A previously well 11-year old right-handed female adolescent presented with a 1-month history of progressive gait ataxia and intermittent headache. On physical examination, she was awake, alert, and able to follow commands. Cranial nerve exam revealed a visual acuity of 20/25 with grade I papilledema on both eyes and bilateral lateral rectus palsy. Sensory and motor testing were normal. Left-sided dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, and vertical nystagmus were also observed. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging showed a 5.4 × 3.7 × 4.1-cm predominantly cystic mass at the left cerebellopontine angle with a 1.4 × 1.5 × 1.5-cm contrast enhancing nodule along with hydrocephalus (Fig. 1).

The tumor was completely excised through a suboccipital retrosigmoid approach. Intraoperatively, clear fluid was seen after opening the cyst. The tumor was well circumscribed, red, multilobulated and vascular with multiple feeding arteries from the cerebellar parenchyma and from the AICA. It had a fair interface with the surrounding structures.

Microscopic examination on routine stain showed a single layer of cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells surrounding a fibrovascular core resembling choroid plexus (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemistry stains were done; GFAP and S100 were positive for the cells of interest, while CK7, CK20, EMA, and TTF-1 were negative, confirming the diagnosis of choroid plexus papilloma.

Postoperatively the patient had complete neurologic recovery. Imaging done 3 months after the surgery showed complete excision of the tumor with resolution of the hydrocephalus and remained shunt free 12 months postresection (Fig. 3).

Materials and methods

A systematic search, conducted in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, of the PubMed and SCOPUS databases was performed using the keywords “choroid plexus papilloma” AND “cerebellopontine angle.” The reference lists of the assessed articles were also searched for relevant studies. All English case reports and case series on patients with choroid plexus papillomas in the choroid plexus were collected. Articles were included if (1) studies were described as either a case report or a case series with individual breakdown of cases; (2) subjects were aged 18 years or less; and (3) the diagnosis of choroid plexus papilloma was confirmed by histopathologic analysis. Articles were excluded if (1) the choroid plexus papillomas were supratentontorial or in the brainstem; and (2) there was no breakdown of individual cases to allow analysis. Data collected included age, sex, clinical features, imaging results, treatment, and outcomes on follow-up.

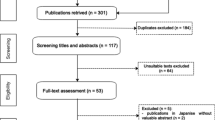

A total of 112 records were identified through a database search. Of these, 45 articles were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts for relevance to the study. The full text of 63 articles were assessed; of which, 55 articles were excluded for the reasons stated above. Eight studies were included in the qualitative analysis (Fig. 4).

Results

A total of eleven cases of pediatric choroid plexus papillomas arising in the cerebellopontine angle were identified from the systematic review (Table 1). The patients’ age ranged from 9 months to 14 years, with a median age of 8 years. There was a slight female predilection (1.2:1).

The most common neurologic manifestations were headache (100%), cerebellar signs (dysmetria, nystagmus, ataxia) (82%), and cranial nerve palsies (VI-IX) (45%). The duration of symptoms ranged from 1 day to 44 months, with a median of 4 months. One patient presented with rapid deterioration due to tumor bleed which presented as subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Imaging showed evidence of hydrocephalus in 73% of patients. On CT, majority of the lesions were hyperdense and almost all exhibited contrast enhancement. On MRI, the lesions appear as lobulated well-defined masses T1 hypo- to isointense with homogenous contrast enhancement while on T2 the lesions appear predominantly hyperintense. The current case presented as a cystic mass with a solid nodule which was not seen in the previous cases.

All patients had surgical treatment and 27% underwent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion. Two patients had preoperative ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) done due to persistently increased intracranial pressure. External ventricular drainage (EVD) or endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) was not done. Of the eleven excisions, a gross total excision was achieved in nine while the extent of resection was not specified in the remaining two. The approach was retrosigmoid suboccipital in five, far lateral suboccipital in two, while the remaining approaches (lateral suboccipital, midline suboccipital) were each done once. The approach used for two cases was not specified.

Outcome was generally favorable in all cases with no deaths reported at median follow-up of 12 months. Only one case had persistence of hydrocephalus after definitive tumor resection. For this case, postresection shunting was done 3 weeks after due to posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Complete neurologic recovery was achieved in seven cases while partial neurologic recovery was reported in two cases.

Discussion

Given the rarity of CPA tumors in children, the differential diagnosis is poorly defined in this population [14]. Different types of tumors can arise in the CPA and can originate from the neuroglia, the neural sheath, the embryonic remnants or the meninges [13, 15]. In the pediatric age group, tumors located in the CPA are frequently as a result of tumor extending from nearby structures such as the brainstem, the cerebral peduncle, the cerebellum, or the fourth ventricle [13]. However, there are tumors that can intrinsically originate in this location which include vestibular schwannomas, meningiomas, epidermoid cysts, arachnoid cysts, lipomas, atypical rhabdoid-teratoid tumors, and gangliogliomas in decreasing order of frequency [13,14,15,16]. Lesions in the CPA mostly present with signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, and similarly the most common presentation in this review was headache [1, 7, 17,18,19]. Also these lesions can also present with mass effect causing compression of the surrounding structures which then manifests as cerebellar signs (dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, nystagmus, ataxia) and cranial nerve palsies (VI-IX) [1, 7,8,9, 11, 12]. Although there can be some prominent symptoms with a particular tumor type such as hearing loss for vestibular schwannomas and acute facial palsy for atypical rhabdoid-teratoid tumors, they can be difficult to differentiate clinically [13, 20]. Hydrocephalus can also be present in patients with CPA tumors due to obstruction of CSF flow, but for choroid plexus papillomas specifically, it can also be as a result of either overproduction of CSF or impaired absorption [3, 17, 21]. In some studies, this was the most common presentation for choroid plexus papillomas; however, this was not the case in this review where only 63% had hydrocephalus [3, 21]. One reason behind this was thought to be that the obstruction of the CSF pathway by a CPP in the cerebellopontine angle was not as severe when compared with an intraventricular CPP. Also, there may be decreased vascular supply at the cerebellopontine angle resulting in the inability of the tumor to overproduce CSF [7, 22, 23]. Median duration of symptoms was 4 months in this review which was longer compared with some studies which ranged from 1 to 4 months [6, 17, 21]. This could be explained by a lower proportion of patients having hydrocephalus in this review. There have been reported cases of incidental discovery of these types of tumors, highlighting its possible indolent nature in some cases [8, 17]. The presentation of pediatric choroid plexus papillomas is usually seen in patients less than 10 years of age [1, 8, 17, 24]. They are especially seen in those less than 5 years of age, but it has been found that infratentorial lesions are present more in older children compared with those found supratentorially [1, 8, 17, 25]. This matches our review where in the median age of cases was at 8 years of age. Majority of studies have shown that choroid plexus papillomas show a male predilection; however, some studies show that lesions located in the cerebellopontine angle are more common in the female population which was similarly observed in this study [1, 2, 4,5,6,7,8, 11, 18, 26, 27].

The imaging findings of choroid plexus papillomas have been well described in literature. On CT, they appear as iso- or hyperdense lesions that enhance with contrast administration similar to what was found in this review. On MRI, they can present as T1 hypo- or isointense or T2 iso- or hyperintense lesions that enhance with gadolinium [1, 7, 11, 21, 22]. Calcifications can also be found in up to 20% of these lesions but none was found in the patients included in this review [1, 6, 7, 21, 22, 24]. Choroid plexus papillomas can present with cysts in 20% of cases [7, 11, 22]. Similar to the illustrated case, they can appear either as pure cystic tumors or as cystic tumors with solitary or multiple mural nodules [28,29,30,31,32]. Cyst formation was postulated to either be from CSF production of the tumor or hemorrhages in the tumor [7, 11] although there was only one radiographically documented case of a choroid plexus papilloma with hemorrhage [10]. Listed in Table 2 are the imaging features of the more common primary tumors of the cerebellopontine angle in children that may help differentiate them from choroid plexus papillomas [14].

The suboccipital retrosigmoid approach is the workhorse approach for tumors in the cerebellopontine angle. This corridor provides a wider field of view to safely dissect any adhesions to the brainstem and the cranial nerves [7]. Similar to our case, the suboccipital retrosigmoid approach was chosen for the above reasons. Those that protrude toward the foramen magnum and are expected to encroach on the lower cranial nerves may benefit from a suboccipital far lateral approach. Doing so would increase the chance of successfully preserving neurologic function and achieving gross total resection [7, 11]. Some have argued that a midline suboccipital approach through the cerebellomedullary fissure is the ideal corridor for resection since it allows early interruption of the vascular supply making tumor debulking much safer [11]. However, this approach is much more suited for tumors located mainly in the fourth ventricle and not for those that are found in the cerebellopontine angle [7]. In this review, 73% of patients presented with hydrocephalus but only 18% of patients underwent preoperative ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion. Managing hydrocephalus can be challenging since there is no clear consensus in treating this feature of the disease. The decision in which option to choose for managing hydrocephalus preoperatively (EVD vs VPS vs ETV) rests on the clinical picture of the patient coupled with the available resources of the treating institution [1, 17, 25]. If the patient presents in extremis due to severe hydrocephalus, external ventricular drainage may be done to arrest herniation. As opposed to endoscopic third ventriculostomy, EVD is preferred in our institution since its placement is expedient, intracranial pressure can be monitored, and CSF drainage can be controlled perioperatively. Furthermore, it can allow the egress of postresection blood and protein products reducing the risk of posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus [33]. Following EVD placement, the tumor resection can then be done once the patient stabilizes. Otherwise, electing to proceed directly with tumor resection in a patient who is not in extremis is a reasonable option given that the hydrocephalus will most likely resolve after complete removal obviating the need for permanent CSF diversion [7, 16, 17, 34]. In this series, only one patient had postresection shunting done due to posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus while the rest of the patients have remained shunt free on 1-year median follow-up. Hydrocephalus should therefore be managed expectantly with close observation and CSF diversion should only be done if clinically necessary [33]. In the event that CSF diversion is needed, it is recommended that endoscopic third ventriculostomy be tried first, as long as the origin of the hydrocephalus is not posthemorrhagic or postinfectious in nature, so that shunt dependency and its complications can be avoided as much as possible [34, 35].

Gross total excision of the tumor (GTR) is the current standard of care for choroid plexus papillomas which was achieved in all of the reviewed cases with the majority achieving complete neurologic recovery [1, 3, 7, 8, 25, 36, 37]. Studies have shown that GTR is the most important variable that can influence the long-term survival of patients with choroid plexus papillomas and that it offers the best likelihood for successful treatment [3, 5, 38]. Some studies have reported 10-year survival rates close to 100% [1, 3, 21]. Currently there is no evidence to support the use of adjuvant therapy to improve survival after GTR and its use has been restricted to recurrent or malignant disease [1, 5, 36]. A “wait and see” approach has been recommended for patients who underwent gross total resection [5, 7]. We have adapted this approach for our patient and at 1-year follow-up, the patient is still asymptomatic and free from disease and free from CSF diversion.

Limitations

The study is a systematic review of case reports and small case series, owing to the rarity of this condition. As such, it is subject to selection bias. For instance, choroid plexus papillomas which do not present acutely and were not surgically managed may be under-reported in the literature. Data we wanted to collect was also incomplete in some reported cases, limiting the analysis.

Conclusion

Choroid plexus papillomas found in the cerebellopontine angle in the pediatric population are extremely rare but they should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment with excellent outcomes achievable in majority of patients.

References

Prasad GL, Mahapatra AK (2015) Case series of choroid plexus papilloma in children at uncommon locations and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int 6(1). Retrieved May 14, 2020. http://surgicalneurologyint.com/Case-series-of-choroid-plexus-papilloma-in-children-at-uncommon-locations-and-review-of-the-literature

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK et al (2016) The 2016 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820

Bettegowda C, Adogwa O, Mehta V, Chaichana KL, Weingart J, Carson BS, Jallo GI, Ahn ES (2012) Treatment of choroid plexus tumors: a 20-year single institutional experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr 10(5):398–405. Retrieved May 25, 2020. Available from: https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg-pediatr/10/5/article-p398.xml

Furuya K, Sasaki T, Saito N, Atsuchi M, Kirino T (1995) Primary large choroid plexus papillomas in the cerebellopontine angle: radiological manifestations and surgical management. Acta Neurochir 135(3–4):144–149

Wolff JEA, Sajedi M, Brant R, Coppes MJ, Egeler RM (2002) Choroid plexus tumours. Br J Cancer 87(10):1086–1091

Tacconi L, Delfini R, Cantore G (1996) Choroid plexus papillomas: consideration of a surgical series of 33 cases. Acta Neurochir 138(7):802–810

Luo W, Liu H, Li J, Yang J, Xu Y (2016) Choroid plexus papillomas of the cerebellopontine angle. World Neurosurg 95(6):117–125. Retrieved May 14, 2020. Available from: http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/10.1007/BF02341477

Trybula SJ, Karras C, Bowman RM, Alden TD, DiPatri AJ, Tomita T (2020) Infratentorial choroid plexus tumors in children. Childs Nerv Syst 1–6. Retrieved May 25, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-020-04532-7

Hammock MK, Milhorat TH, Breckbill DL (1976) Primary choroid plexus papilloma of the cerebellopontine angle presenting as brain stem tumor in a child. Childs Brain 2(2):132–142

Piguet V, De Tribolet N (1984) Choroid plexus papilloma of the cerebellopontine angle presenting as a subarachnoid hemorrhage: case report. Neurosurgery. 15(1):114–116

Talacchi A, De Micheli E, Lombardo C, Turazzi S, Bricolo A (1999) Choroid plexus papilloma of the cerebellopontine angle: a twelve patient series. Surg Neurol 51(6):621–629. Retrieved May 14, 2020. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090301999000245

Spallone A, Pastore FS, Hagi MO (1986) Choroid plexus papillomas of the cerebellopontine angle in a child. Ital J Neurol Sci 7(6):613–616. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.094

Tomita T, Grahovac G (2015) Cerebellopontine angle tumors in infants and children. Childs Nerv Syst 31(10):1739–1750

Holman MA, Schmitt WR, Carlson ML, Driscoll CLW, Beatty CW, Link MJ (2013) Pediatric cerebellopontine angle and internal auditory canal tumors. J Neurosurg Pediatr 12(4):317–324

Phi JH, Wang KC, Kim IO, Cheon JE, Choi JW, Cho BK, Kim SK (2013) Tumors in the cerebellopontine angle in children: warning of a high probability of malignancy. J Neuro-Oncol 112(3):383–391

Zúccaro G, Sosa F (2007) Cerebellopontine angle lesions in children. Childs Nerv Syst 23(2):177–183

Ogiwara H, Dipatri AJ, Alden TD, Bowman RM, Tomita T (2012) Choroid plexus tumors in pediatric patients. Br J Neurosurg 26(1):32–37

Safaee M, Clark AJ, Bloch O, Oh MC, Singh A, Auguste KI, Gupta N, McDermott MW, Aghi MK, Berger MS, Parsa AT (2013) Surgical outcomes in choroid plexus papillomas: an institutional experience. J Neuro-Oncol 113(1):117–125

Kapoor A, Aggarwal A, Ahuja C, Salunke P (2016) Primary choroid plexus papilloma of cerebellopontine angle: an unusual entity in infancy. J Pediatr Neurosci 11(3):287–288

Siu A, Lee M, Rice R, Myseros JS (2014) Association of cerebellopontine angle atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors with acute facial nerve palsy in infants: report of 3 cases. J Neurosurg Pediatr 13(1):29–32

Pencalet P, Sainte-Rose C, Lellouch-Tubiana A, Kalifa C, Brunelle F, Sgouros S, Meyer P, Cinalli G, Zerah M, Pierre-Kahn A, Renier D (1998) Papillomas and carcinomas of the choroid plexus in children. J Neurosurg 88(3):521–528

Shin JH, Lee HK, Jeong AK, Park SH, Choi CG, Suh DC (2001) Choroid plexus papilloma in the posterior cranial fossa: MR, CT, and angiographic findings. Clin Imaging 25(3):154–162

Shi YZ, Wang ZQ, Xu YM, Lin YF (2014) MR findings of primary choroid plexus papilloma of the cerebellopontine angle: report of three cases and literature reviews. Clin Neuroradiol 24(3):263–267

Koeller KK (2002) From the archives of the AFIP cerebral Intraventricular neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 22:3691473–3691505

Lena G, Genitori L, Molina J, Legatte JRS, Choux M (1990) Choroid plexus tumours in children. Review of 24 cases. Acta Neurochir 106(1–2):68–72. Retrieved May 25, 2020. Available from: http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/10.1007/BF01809335

Laurence KM (1979) The biology of choroid plexus papilloma in infancy and childhood. Acta Neurochir 50(1–2):79–90

Sarkar C, Sharma MC, Gaikwad S, Sharma C, Singh VP (1999) Choroid plexus papilloma: a clinicopathological study of 23 cases. Surg Neurol 52(1):37–39

Emami-Naeini P, Nejat F, Khashab M (2008) Cystic choroid plexus papilloma with multiple mural nodules in an infant. Childs Nerv Syst 24(5):629–631

Tomita T, McLone DG, Naidich TP (1986) Mural tumors with cysts in the cerebral hemispheres of children. Neurosurgery 19(6):998–1005. Retrieved May 25, 2020. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/neurosurgery/article/19/6/998/2752804

Murata M, Morokuma S, Tsukimori K, Hojo S, Morioka T, Hashiguchi K, Sasaki T, Wake N (2009) Rapid growing cystic variant of choroid plexus papilloma in a fetal cerebral hemisphere. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 33(1):116–118. Retrieved May 25, 2020. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/uog.6262

Miyagi Y, Natori Y, Suzuki SO, Iwaki T, Morioka T, Arimura K et al (2006) Purely cystic form of choroid plexus papilloma with acute hydrocephalus in an infant: Case report. J Neurosurg 105 PEDIAT(SUPPL. 6):480–484

Patanakar T, Prasad S, Mukherji SK, Armao D (2000) Cystic variant of choroid plexus papilloma. Clin Imaging 24(3):130–131

Lam S, Reddy G, Lin Y, Jea A (2015) Management of hydrocephalus in children with posterior fossa tumors. Surg Neurol Int 6:S346–S348

Fritsch MJ, Doerner L, Kienke S, Mehdorn HM (2005) Hydrocephalus in children with posterior fossa tumors: Role of endoscopic third ventriculostomy. J Neurosurg 103 PEDIAT(SUPPL. 1):40–42

Schijman E, Peter JC, Rekate HL, Sgouros S, Wong TT (2004) Management of hydrocephalus in posterior fossa tumors: how, what, when? Childs Nerv Syst 20(3):192–194

Safaee M, Oh MC, Sughrue ME, Delance AR, Bloch O, Sun M et al (2013) The relative patient benefit of gross total resection in adult choroid plexus papillomas. J Clin Neurosci 20(6):808–812. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2012.08.003

Krishnan S, Brown PD, Scheithauer BW, Ebersold MJ, Hammack JE, Buckner JC (2004) Choroid plexus papillomas: a single institutional experience. J Neuro-Oncol 68(1):49–55

Packer RJ, Perilongo G, Johnson D, Sutton LN, Vezina G, Zimmerman RA, Ryan J, Reaman G, Schut L (1992) Choroid plexus carcinoma of childhood. Cancer. 69(2):580–585

Acknowledgments

BAA – neuroradiology, JIB – surgery, MCM – neuropathology, MGM – neuroradiology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaddi, M.J.S., Lappay, J.I., Chan, K.I.P. et al. Pediatric choroid plexus papilloma arising from the cerebellopontine angle: systematic review with illustrative case. Childs Nerv Syst 37, 799–807 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-020-04896-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-020-04896-w