Abstract

Purpose

Many techniques were used for the treatment of hydrocephalus, and ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery is a widely used procedure. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery has been associated with several complications like obstruction of the tube, infection, cerebrospinal fluid loculation, intestinal obstruction, migration of the shunt, and perforation of the intestinal organs. Perforation of the bowel owing to protrusion of ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter from the anus is an extremely rare complication. Mini or exploratory laparotomy and revision of peritoneal part of shunt and repair of bowel perforation, or pulling out the ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter and using external ventricular drainage and antibiotics, or colonoscopic removal of ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter and repair of the bowel can be performed. Retrograde contamination of cerebrospinal fluid and meningitis is a very important part of the treatment in these cases. We aimed to present two cases with bowel perforation who treated with endoscopically.

Methods

We report the cases of 2 patients with transanal protrusion of VPS catheter and the management via endoscopic therapeutic options.

Results

Successful treatment of the patients was achieved by endoscopic removal of the catheter and endoscopic repair of the bowel perforation.

Conclusion

If peritonitis, bowel obstruction, or abscess does not occur, endoscopic removal of shunt and bowel repairing with endoclips may be enough.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) surgery is a widely used procedure in the treatment of hydrocephalus since it was described by Kausch in 1905 [1]. Complications of VPS surgery include obstruction of the tube, infection, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) loculation, intestinal obstruction, migration of the shunt and perforation of the intestinal organs [2, 3]. Perforation of the bowel owing to protrusion of VPS catheter from the anus is an extremely rare complication, occurring in 0.1–0.7% of the patients [4]. For treatment, mini or exploratory laparotomy and revision of peritoneal part of shunt and repair of bowel perforation, pulling out of the VPS catheter and using external ventricular drainage and antibiotics or colonoscopic removal of VPS catheter and bowel repair can be performed [5, 6]. Endoscopic treatment options, albeit limited, have been introduced in recent years. Here we report the cases of 2 patients with transanal protrusion of VPS catheter. Successful treatment of patients was achieved by endoscopic removal of the catheter and closure of bowel perforation using an endoclip.

Case 1

A 1.5-year-old girl was brought to the hospital owing to vomiting and restlessness. Her mother stated complaints of protruded catheter from the girl’s anus. She had undergone surgery for myelomeningocele, and a VPS catheter was inserted for hydrocephalus in the neonatal period at another hospital.

Physical and neurological examination revealed no abnormalities. However, the rectal examination exhibited protruded catheter from the anus (Fig. 1a). Leukocytes were not noted in the microscopic examination of CSF obtained by lumbar puncture.

Abdominal X-ray and computed tomography (CT) revealed the catheter trace in the transverse colon with no intestinal obstruction finding such as free air. Brain CT showed no abnormalities (Fig. 1b–d).

For the treatment, we disconnected the proximal catheter, removed the distal catheter and endoscopically repaired the perforation using an endoclip (Fig. 2a, b). We inserted a new VPS catheter in the same session. She was discharged without any complications.

Case 2

A 2.5-year-old boy was brought to the emergency service owing to nausea, vomiting, restlessness and fever. The patient had a history of acute meningitis caused by Escherichia coli 3 months earlier which was treated with ceftriaxone and placement of a VPS catheter during the neonatal period.

On physical examination, his vital signs were normal, except for fever and neck stiffness, and there was no catheter protrusion from the anus. Blood laboratory test results revealed an increase in C-reactive protein. Lumbar puncture revealed decreased glucose levels, increased protein levels and increased polymorphonuclear neutrophils.

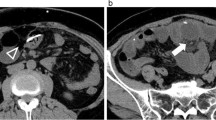

Abdominal CT and X-ray demonstrated the lying catheter, extending from the transvers colon to the sigmoid colon (Fig. 3a, b).

For treatment, the same endoscopic surgical technique was used (Fig. 4a, b). Following shunt removal, an external ventricular drain was inserted for 2 days, and we recognised that there was no need for a shunt. We did not insert a new VPS catheter after treating meningitis. He was then discharged without any complications.

Discussion

The most common complications of VPS surgery are obstruction and infection. Intestinal perforation and anal protrusion of the catheter is uncommon [7]. There are several treatment options for intestinal perforation, and there is no clear consensus in this regard in the literature. An abdominal X-ray and CT should be used to assess the catheter trace and bowel obstruction. Brain CT shows possible pneumocephalus, hydrocephalus, abscess or hematoma. If additional cranial or abdominal pathology which requires surgery is noted, the treatment protocol should be accordingly devised.

The aetiology of perforation is often chronic contact between the catheter and bowel. Authors also state the silicone allergy, the usage of the long catheters, intra-abdominal negative pressure, local inflammatory reaction and fibrosis around the distal catheter, the types and the shapes of catheters and the effect of gravity as the possible causes of perforation. Furthermore, myelomeningocele causes thinning of the bowel wall owing to impaired innervation of the intestinal system [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Chronic contact and fibrosis cause the perforation of the bowel wall. Fibrosis may prevent the development of abdominal infection, but not in all cases. Yousfi et al. reported that the rate of clinical peritonitis is approximately 25%, and rate of meningitis–ventriculitis is 43–48% of the reported cases [14].

Birbilis et al. reported a shunt displacement case with peritonitis findings. Intestinal resection and anastomosis were performed for the surgical treatment of peritonitis [8].

Ghritlaharey et al. reported 10 patients with bowel perforation owing to VPS catheter displacement. They performed mini-laparotomy and revision of the peritoneal shunt catheter in 7 patients. Shunt removal was performed in 3 patients. Shunt revision was delayed in 2 of the 3 patients. None of the patients showed peritonitis and intestinal obstruction findings; therefore, formal abdominal exploration and bowel repairing was not needed in any patient [4].

Peritonitis owing to bowel perforation plays a vital role in the treatment of these patients. Fortunately, encasing fibrosis around the catheter and bowel prevents the development of abdominal infection; however, the incidence of peritonitis has been reported in approximately 25% patients [14]. Chen reported peritonitis following endoscopic removal as an unusual complication [5]. Chiang LL et al. declared that leaving the bowel perforation unrepaired may still put the patient at risk of subsequent peritonitis [15]. For treatment, some authors advocate catheter removal by rectosigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. However, there are few articles on this subject [5, 16,17,18,19]. Endoscopic treatment is a minimally invasive procedure but does not eliminate the risk of peritonitis. Alves et al. reported closure of the bowel perforation using an endoclip to repair the bowel wall and prevent peritonitis. They concluded that the application of endoclips is a simple endoscopic procedure which may prevent peritonitis [19]. However, in the case of bowel obstruction, peritonitis or abscess, laparotomy is required [4].

Abdominal pathologies, such as obstruction, peritonitis or abscess, were not identified in our patients. Therefore, we disconnected the distal catheter from the shunt pump and pulled out the distal catheter using endoscopic forceps, and the perforation was endoscopically repaired using an endoclip. Patients were discharged without any complications.

Conclusion

In patients without peritonitis, abscess or bowel obstruction, endoscopic removal and perforation repair with endoclips may be a good surgical alternative. We believe that randomised prospective studies will provide more precise information in the future.

References

Lifshutz JI, Johnson WD (2001) History of hydrocephalus and its treatments. Neurosurg Focus 11(2):1. https://doi.org/10.3171/foc.2001.11.2.2

Agha FP, Amendola MA, Sihirazi KK, Amendola BE, Chandler WF (1983) Unusual abdominal complications of ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Radiology 146:323–326

Surchev J, Georgiev K, Enchev Y, Avramov R (2002) Extremely rare complications in cerebrospinal fluid shunt operations. J Neurosurg Sci 46:100–102

Ghritlaharey RK, Budhwani KS, Shrivastava DK, Gupta G, Kushwaha AS, Chanchlani R, Nanda M (2007) Trans-anal protrusion of ventriculo-peritoneal shunt catheter with silent bowel perforation: Report of ten cases in children. Pediatr Surg Int 23:575–580

Chen HS (2000) Rectal penetration by a disconnected ventriculoperitoneal shunt tube: an unusual complication. Chang Gung Med J 23:180–184

Sharma A, Pandey AK, Radhakrishnan M, Kumbhani D, Das HS, Desai N (2003) Endoscopic management of anal protrusion of ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Indian J Gastroenterol 22:29–30

Mohta A, Jagdish S (2009) Spontaneous anal extrusion of ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Afr J Paediatr Surg 6(1):71–72

Birbilis T, Zezos P, Liratzopoulos N, Oikonomou A, Karanikas M, Kontogianidis K, Kouklakis G (2009) Spontaneous bowel perforation complicating ventriculoperitoneal shunt: A case report. Cases J 2:8251

Brownlee JD, Brodkey JS, Schaefer IK (1998) Colonic perforation by ventriculoperitoneal shunt tubing: A case of suspected silicone allergy. Surg Neurol 49:21–24

Ibrahim AW (1998) E. coli meningitis as an indicator of intestinal perforation by V-P shunt tube. Neurosurg Rev 21:194–197

Sathyanarayana S, Wylen EL, Baskaya MK, Nanda A (2000) Spontaneous bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery: case report and a review of 45 cases. Surg Neurol 54:388–396

Vinchon M, Baroncini M, Laurent T, Patrick D (2006) Bowel perforation caused by peritoneal shunt catheters: diagnosis and treatment. Neurosurgery 58(suppl 1):ONS76–ONS82. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000192683.26584.34

Matsuoka H, Takegami T, Maruyama D, Hamasaki T, Kakita K, Mineura K (2008) Transanal prolapse of ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 48:526–528

Yousfi MM, Jackson NS, Abbas M, Zimmerman RS, Fleischer DE (2003) Bowel perforation complicating ventriculoperitoneal shunt: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc 58:144–148

Chiang LL, Kuo MF, Fan PC, Hsu WM (2010) Transanal repair of colonic perforation due to ventriculoperitoneal shunt: Case report and review of the literature. J Formos Med Assoc 109:472–475

Oliveira SB, Monteiro IM (2011) Endoscopic management of transanal protrusion of subdural peritoneal shunt in a child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 53:465–467

Vuyyuru S, Ravuri SR, Tandra VR, Panigrahi MK (2009) Anal extrusion of a ventriculo peritoneal shunt tube: endoscopic removal. J Pediatr Neurosci 4:124–126

Pikoulis E, Psallidas N, Daskalakis P, Kouzelis K, Leppäniemi A, Tsatsoulis P (2003) A rare complication of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt resolved by colonoscopy. Endoscopy 35:463

Alves AR, Mendes S, Lopes S, Monteiro A, Perdigoto D, Amaro P, Tomé L (2017) Endoscopic management of colonic perforation due to ventriculoperitoneal shunt: case report and literature review. GE Port J Gastroenterol 24(5):232–236. https://doi.org/10.1159/000454987

Funding

This study did not receive any financial support from any person or institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consents for the publication of the report were obtained from the parents of the children.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

İştemen, İ., Arslan, A., Olguner, S.K. et al. Bowel perforation of ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter: endoscopically treated two cases. Childs Nerv Syst 37, 315–318 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-020-04709-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-020-04709-0