Abstract

Purpose

Catheter-related infection is a major complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt in children. The aim of this study is to determine inflammatory response and the efficacy of polypropylene-grafted polyethylene glycol (PP-g-PEG) copolymer and silver nanoparticle-embedded PP-g-PEG (Ag-PP-g-PEG) polymer-coated ventricular catheters on the prevention of catheter-related infections on a new experimental model of ventriculoperitoneal shunt in rats.

Methods

Thirty six Wistar albino rats were divided into six groups: group 1, unprocessed sterile silicone catheter-embedded group; group 2, sterile PP-g-PEG-coated catheter group; group 3, sterile Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated catheter group; group 4, infected unprocessed catheter group; group 5, infected PP-g-PEG-coated catheter group; and group 6, infected Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated catheter group, respectively. In all groups, 1-cm piece of designated catheters were placed into the cisterna magna. In groups 4, 5, and 6, all rats were infected with 0.2 mL of 10 × 106 colony forming units (CFU)/mL Staphylococcus epidermidis colonies before the catheters were placed. Thirty days after implantation, bacterial colonization in cerebrospinal fluid and on catheter pieces with inflammatory reaction in the brain parenchyma was analyzed quantitatively.

Results

Sterile and infected Ag-PP-g-PEG-covered groups revealed significantly lower bacteria colony count on the catheter surface (ANOVA, 0 ± 0, p < 0.001; 1.08 ± 0.18, p < 0.05, respectively). There was moderate inflammatory response in the parenchyma in group 4, but in groups 5 and 6, it was similar to that of the sterile group (ANOVA, 16.33 ± 3.02, p < 0.001; 4.00 ± 0.68, p < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusions

The PP-g-PEG, especially Ag-PP-g-PEG polymer-coated ventricular catheters are more effective in preventing the catheter-related infection and created the least inflammatory reaction in the periventricular parenchyma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The most widely used treatment for hydrocephalus is shunting excessive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into an extracranial body compartment, especially into the abdominal space, under the peritoneum, which is named as ventriculoperitoneal shunt [16, 17]. However, the risk of cerebrospinal fluid infection is associated with this procedure [32]. Since infection remains a major problem with CSF diversion procedures, different kinds of catheters were introduced to overcome the infection risk in ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheters. The investigation of the efficacy of these newly formed catheters is mostly done by in vivo experiments on animals, especially on hydrocephalic ones. An indispensible step in designing these experiments is to choose a proper animal model. Researchers should overcome many struggling steps to form a proper experimental model. First of all, one should generate hydrocephalus in the tested animal [5, 19] or should start the experiment with a mutant hydrocephalic animal which is hard to obtain. Also, to repeat the exact shunt replacement in an animal as in a human being, one should use a bigger canine model such as a dog or a lamb [3, 14, 38]. Since these animals are vulnerable and hard to obtain, the experiment cannot be designed with higher number of animals because of the ethical concerns. Therefore, there is a need for an easier and faster ventriculoperitoneal shunt model which can be applicable to any kind of animal, especially nonhydrocephalic rats. The great cistern is a favorable area in rats as being a large and easily accessible CSF cavity [7, 44]. Moreover, the great cistern is a safe point for CSF collection [17, 22]. We have introduced a novel experimental ventriculoperitoneal shunt model in rats, in which we placed the proximal end of the catheter to the great cistern and distal end in between the posterior cervical muscle layer. By this way, we have planned to obtain an effective ventriculoperitoneal shunt system which works in nonhydrocephalic rats and drains the CSF from the great cistern to subcutaneous tissue under the skin of the abdomen.

With this present study, we have also introduced a novel shunt catheter which has a modified surface. In literature, many different catheter types, such as antimicrobial catheters, were tested for ventricular drainage in a ventriculoperitoneal shunt system [29]. Although these catheters decrease the infection rate in single patient, they are found to induce resistant [30, 44] bacteria which might lead to even greater health care problems [8, 27]. A new approach which might overcome these problems is provided by catheters impregnated with silver nanoparticles, and they have been shown to reduce infections in both central venous catheters and ventricular catheters [11, 39]. Although silver is known to have toxic and inflammatory effect on brain tissue [11, 24, 40], it was previously demonstrated that there is no risk of a toxic effect due to silver release into the CSF [11]. Another way to overcome infection in a shunt system is to modify the surface of the catheter and therefore prevent bacteria attachment to the catheter surface.

Polypropylene (PP) is a well-known hydrophobic polymer which has good mechanical properties and has many medical applications, such as tissue replacement and organ wall reconstructions [15, 20]. However, to obtain a wider medical application, nanoparticles can be embedded, and hydrophilic groups can be introduced into this polymer to overcome its hydrophobic character via postpolymerization reactions [2, 18, 21, 22]. We have previously investigated the soft tissue response of polypropylene-grafted polyethylene glycol (PP-g-PEG) amphiphilic graft copolymer film and its nanocomposite version containing gold nanoparticles in rats, under the skin, and found out that these polymer patches have good soft tissue response [14]. In this present study, we have modified the outer and inner surface of the catheter via covering it with PP-g-PEG polymer casts and silver nanoparticle-embedded PP-g-PEG (Ag-PP-g-PEG) casts. Then we used these novel processed catheters in a new ventriculoperitoneal shunt model in nonhydrocephalic rats and investigated the antimicrobial effect and central nervous system responses of these catheters.

Materials and method

PEG4000, chlorinated polypropylene (PP-Cl), sodium hydride (NaH), and the solvents were all purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification. Medical grade silicone ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheters were obtained from Sophysa SA, Orsay, France. Thirty six silicone ventricular catheter pieces in 1-cm length were prepared and covered with polymer cast as described below.

Synthesis of pure and silver nanoparticles embedded PP-g-PEG amphiphilic graft copolymers covered ventricular shunt catheters

The synthesis of PP-g-PEG and Ag nanoparticles embedded PP-g-PEG was explained in our previous study in detail [18]. Briefly, the Williamson-ether-synthesis-like reaction between PEG and PP-Cl was performed in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solution in the presence of sodium hydride. A typical endcapping reaction was performed as follows: PEG-2000 (5.0 g, 2.5 mmol) and PP-Cl (1.43 g, 1.0 mmol Cl) were mixed and dissolved in dry THF (10 mL). To the solution, NaH (0.12 g, 5 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature under argon for 3 days. The reaction mixture was poured into 200 mL water containing 1 mL of concentrated HCl. For the purification, the crude polymer was redissolved in chloroform and reprecipitated in 200 mL of methanol. The purified polymer was dried under vacuum at room temperature overnight. 1H-NMR and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the polymer sample confirmed the structure with 20 mol% of PEG content. Then, 0.5 g of the amphiphilic copolymer was dissolved in 20 mL of chloroform. A shunt catheter was cut into 1-cm length equal pieces. Twelve catheter pieces were dipped into this polymer solution, and the inner and outer surfaces of catheter were covered with the polymer. Then they were allowed to evaporate leaving a thin polymer film on the catheter. The processed catheter pieces were washed with methanol and dried under vacuum. To confirm the presence of a very thin polymer layer covering the silicon shunt, FTIR spectra analysis was done, and characteristic additional signal was at 1,643 cm−1 captured on both PP-PEG-covered and nanoparticle-embedded PP-PEG-covered shunts.

For silver nanoparticles embedded PP-g-PEG amphiphilic graft copolymers, aqueous solutions of AgNO3 0.1 M and the reducing agent, NaBH4 (0.1 M), were prepared separately. The PP-g-PEG2000 graft copolymer (0.2 g) was dissolved in 20 mL of THF. To this solution, 0.10 mL of the AgNO3 aqueous solution was added, and it was vigorously stirred at room temperature for 10 min. Then the same volume of the reducing agent (0.10 mL of NaBH4 aqueous solution) was added to this mixture, generating a deep red colloidal solution. The polymer solution containing Ag nanoparticles was coded as Ag-PP-g-PEG. Twelve catheter pieces were covered with Ag-PP-g-PEG similarly as described above. Twelve unprocessed silicone catheter pieces and twenty four processed catheter pieces were sterilized individually using ethylene oxide gas with an exposure time of 8 h.

Experimental design of ventriculoperitoneal shunt implantation and ventriculitis

Thirty six female Wistar albino rats with an average weight of 250 g were randomly divided into six groups: group 1, unprocessed sterile silicone catheter-embedded group; group 2, sterile PP-g-PEG-coated silicone catheter group; group 3, sterile Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated silicone catheter group; group 4, infected unprocessed catheter group; group 5, infected PP-g-PEG-coated silicone catheter group; and group 6, infected Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated silicone catheter group, respectively. They were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 mL/kg alphazyn and 0.3 mL/kg ketamin mixture. All procedures were carried out in compliance with the Hacettepe University Ethical Committee. The animals did not receive any antibiotic prophylaxis before or after the surgical procedure for implantation of the shunt system or bacterial inoculation.

The rats were placed in a lateral decubitis position with the head flexed at 45°. After proper shaving and sterilization, a 3-cm midline vertical incision was made on the craniovertebral junction of all the animals. Following the dissection of the muscle layer, the atlantooccipital membrane and the great cistern were visualized (Fig. 1).

In sterile groups (groups 1, 2, and 3), 5-mm vertical incision was made to the dura, and the great cistern was exposed in 18 rats. One-centimeter length of silicone catheter was implanted into the great cistern with a half portion of the catheter remained in between the muscle layer of each six rats individually (Fig. 2).

PP-g-PEG-coated catheter piece in 1-cm length was implanted to each six rats in the same manner in the second group (PP-g-PEG-coated catheter-embedded group), and Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated catheter piece was placed to another six rats again in the same fashion in the third group (Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated catheter-embedded group). For infected groups 4, 5, and 6, 0.2 ml of Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteria solution (1.0 × 106 colony forming units (CFU)/mL) in Ringer’s lactate solution was inoculated to the great cistern before the dura is opened. Then three different catheter pieces were placed into six rats in each of three groups in similar fashion as described for the sterile groups. All rats were observed for neurological symptoms such as paresis, meningeal irritation signs, and surgical site infection. After 30 days of operation, the animals were euthanized, and CSF samples, embedded catheter pieces, and brain tissue samples were collected from all animals for further analysis.

Histochemical analysis

For histological analysis, the right cerebrum was immersion-fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Coronal slices were embedded in paraffin. Sections (6-μm thickness) at the level of the optic chiasm, containing the lateral ventricle wall, were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Four random regions were examined at 40× magnification, and the inflammatory cells were counted in each section on the periventricular parenchyma. The final value was recorded as an average of these four different measurements.

Culturing and bacterial count

After the incubation period, the catheters were removed and inoculated on sheep’s blood agar plates using the semiquantitative procedure as previously described [42]. This procedure was applied to each catheter piece separately for all groups [6, 38].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done with general linear models, the univariate analysis of variance test, using the SPSS 11.5 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The value p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data of number of colonies on the catheter surface and in the CSF for all groups were converted to log 10.

Results

The great cistern was explored in the 36 rats. We have implanted half of the catheter into the great cistern with the other half 0.5 cm left in between the muscle layer. After 30 days of implantation, complications such as obstructive hydrocephalus or formation of CSF cyst beneath the surgical site were not detected in any rat. In 18 rats, we have applied 2 mL of bacteria suspension containing S. epidermidis colonies, and in all rats, bacteria colony count were over 1,500 in both CSF and catheter itself, supporting the diagnosis of ventriculitis [19]. Light microscopic analysis of the periventricular parenchyma also revealed moderate inflammatory findings with lymphocyte accumulation, supporting ventriculitis. However in infected groups (groups 4, 5, and 6), all rats were lethargic, and in the three rats in group 4 (silicone catheter group), there were surgical site infection signs beginning on the 14th day of infection (Fig. 3).

Bacteria count

The bacteria colony count in CSF and on catheter piece in sterile groups 1, 2, and 3 were very low; however, among the three groups, the highest bacteria colony count was present in the silicone catheter piece (8.33 ± 1.32 CFU/mL; Table 1). Ag-PP-g-PEG- and PP-g-PEG-coated catheter pieces bared the lowest bacteria count in CSF (0.12 ± 0.12 CFU/mL, 0 ± 0 CFU/mL; log 10) and on the catheter surface (0 CFU/mL, 0 CFU/mL; log 10); however, this difference was not found to be statistically significant for bacteria count on the catheter surface and in CSF within the sterile groups (ANOVA, p > 0.05; Table 1).

Highest number of bacteria colonies in CSF cultures was present in group 4 (silicone catheter group) (3.14 ± 0.12 CFU/mL, log 10) among the infected groups, and the least bacteria colony count in CSF was present in Ag-PP-g-PEG group (2.88 ± 0.58 CFU/mL, log 10; Table 1). Bacteria colony count on PP-g-PEG-coated catheter was low compared to that of the infected silicone catheter, and this difference was statistically significant. When the Ag-PP-g-PEG catheter was cultured, it revealed the least bacteria count among the three groups, and this difference was statistically significant compared to groups 4 and 5 (ANOVA, 1.08 ± 0.18 CFU/mL, p < 0.005).

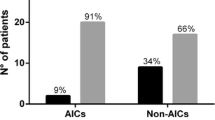

Inflammatory response

When the central nervous tissue response was evaluated for sterile silicone catheter group, there were mild inflammatory changes with little lymphocyte accumulation within the parenchyma and mild periventricular edema (7.17 ± 0.48 lymphocytes/microscopic area; Table 2). Lymphocyte count in group 3 (1.83 ± 0.31 lymphocytes/microscopic area) was significantly lower than those in groups 1 (ANOVA, p < 0.001) and 2 (6.00 ± 0.58 lymphocytes/microscopic area); however, the parenchyma changes were similar with the first group. There was no necrosis or vascular thrombosis within the parenchyma.

When the histochemical response was evaluated in infected groups, the periventricular parenchyma revealed the highest lymphocyte accumulation (16.33 ± 3.02 lymphocytes/microscopic area) with increased edematous areas in silicone catheter group rats (Fig. 4a, b).

In PP-g-PEG-coated catheter group (group 5), edema in the parenchyma was mild, with few lymphocytes underneath the periventricular lining (7.67 ± 0.84 lymphocytes/microscopic area). On the other hand, Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated catheter group revealed very few inflammatory cells (4.00 ± 0.68 lymphocytes/microscopic area) without obvious edema in the periventricular parenchyma (Fig. 5a, b).

Discussion

In this study, we introduce a novel PP-g-PEG and Ag nanoparticle-embedded PP-g-PEG polymer-covered silicone catheter, and to investigate the central nervous system tissue response of these catheters, we have designed an easy and rapidly performed experimental animal model for ventriculoperitoneal shunt implantation.

In literature, there have been many experimental designs for the investigation of catheter-related infection and new catheter designs. In designing a proper experimental animal model of ventriculoperitoneal shunt, hydrocephalic animals are the primary choice. Induction of hydrocephalus in animals is rather troublesome and takes a double time of the experiment; otherwise, mutant animal species must be used. On the other hand, a bigger ventricular space is needed in most of the cases, and so dogs [3] or lambs are mostly preferred. However, the number of these animals is limited because of the ethical concerns, and therefore, statistical analysis and significance cannot be compared with the clinical trials. For these reasons, we chose rats [14, 38] as an experimental test subject, since they are easily found and more resistible to infections. The great cistern is determined as the entry point for placing catheter pieces, because it is easy to expose and has the greatest space bearing CSF [7, 19, 28]. In order to mimic the human ventriculoperitoneal shunt model, we have implanted half of the catheter into the great cistern with the other half 0.5 cm left in between the muscle layer. Since the intraperitoneal side of the catheter may influence the bacterial diversity and contaminate the catheter with other types of bacteria rather than S. epidermidis colonies [26, 41], we have decided to keep the distal end of the catheter only at 0.5 cm and keep it under the skin of the back of the rat. To our knowledge, the previously mentioned ventricular shunt model is the first documented design in nonhydrocephalic rats in literature.

The most common catheter-related complication is infection, especially ventriculitis which is a highly morbid condition [5, 9]. The incidence of catheter-related infection is 5–15% [25, 33, 34, 41]. Gram-positive Staphylococcus species, especially S. epidermidis is the cause of catheter-related infection in humans [26, 33]. The surface proteins of these microorganisms play an important role in the binding of the organism to the shunt material [25].There are several attempts to overcome this disadvantage. One should either add an antimicrobial effect on the surface of the catheter, antibiotic [4, 29, 43] or silver-bearing catheters [10], or modify the surface of the catheter to prevent the attachment of the bacteria [6]. It is shown that bacteria colonization on silver ion attached to catheters is less compared to silicone catheters [10]. Although silver is known to have a toxic and inflammatory effect on brain tissue, silver segregation from the catheter to the brain tissue and CSF is not detectable [10, 11]. With all these knowledge, one can hypothesize that the antimicrobial effect of the catheter can be doubled with modifying the surface of the catheter and adding silver nanoparticles at the same time.

Polypropylene is an unbreakable, elastic, and hydrophobic polymer, which is used as a good substitute to reinforce weakened soft tissue, for example, inguinal or incisional hernias and abdominal wall or pelvic floor defects [15, 20, 37]. In order to broaden its medical applications, one approach is to prepare block copolymers containing hydrophilic blocks that can modify the hydrophilicity, crystallinity, mechanical properties, and biocompatibility of the original material [37]. In this regard, polyethylene glycol can be used as it is a popular hydrophilic and biocompatible polymer. It has been shown that PEG-grafted copolymers have the ability to reduce platelet adhesion and bacterial repulsion [23]. In our previous study, we have already shown that PP-g-PEG patches have good soft tissue response, and the biocompatibility of the polymer is increased as more of a PEG side chain is added [14]. Many studies have reported that hydrophilic surfaces, such as PEG-grafted polymers, suppress protein adsorption and platelet adhesion [12, 18, 45]. These surface characteristics help this graft copolymer to reduce protein deposition that promotes pathogen adhesion and growth on device surfaces [31, 35, 36]. Furthermore, nanoparticles embedded into the polymer structure were reported to enhance the biocompatibility and antimicrobial effect of the polymer itself [13, 18]. Therefore, polypropylene can be modified to form a more biocompatible and antimicrobial polymer for in vivo applications via attaching nanoparticles and PEG side chains.

In our study, we have covered the surface of a silicone shunt catheter with PP-g-PEG and Ag-PP-g-PEG polymer casts, and the result was an enhanced antimicrobial effect with both processed catheters, especially with Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated ones. The polymer coating of a medical device such as cell proliferation surfaces has been previously done by researchers. The spin- or dip-coating approaches, as polymer-coating processes, were shown to be successfully sticking onto the surface of the device [1]. With this present study, we have used the same polymer-coating technique on the ventricular shunt catheter, and detected that the antimicrobial effect of PEG side chains are doubled with Ag nanoparticle attachment. Also, the central nervous system response of these catheters was not different compared to unprocessed silicone catheters. In all PP-g-PEG- and Ag-PP-g-PEG-coated catheters implanted in test animals, there was a negligible brain parenchyma response with very mild inflammatory reaction. This finding proves that these modified catheters can be safely used in the central nervous system. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt in the modification of the surface of the catheter by covering the catheter with a polymer cast.

Conclusion

This study is designed to investigate the efficacy of a newly developed PP-g-PEG and Ag-PP-g-PEG polymer-coated shunt catheters in preventing the shunt infection. PP-g-PEG coated, especially Ag-PP-g-PEG polymer coating is an effective and superior way, compared to unprocessed silicone catheter, to prevent implant-related infections in the central nervous system. Also, this newly introduced experimental design of ventricular shunt model in rats is found to be an easy and effective technique in the investigation of ventricular shunt infection. Therefore, this novel shunt model in rats with newly processed ventricular catheters seems favorable and applicable for further studies.

References

Ajiro H, Akashi M (2010) Cell proliferation on stereoregular isotactic-poly(propylene oxide) as a bulk substrate. Biomacromolecules 11(11):2840–2844

Balci M, Alli A, Hazer B, Güven O, Cavicchi K, Cakmak M (2010) Synthesis and characterization of novel comb-type amphiphilic graft copolymers containing polypropylene and polyethylene glycol. Polym Bull 64:691–705

Bayston R, Brant C, Dombrowski CM, Hall G, Tuohy M, Procop G, Luciano MG (2008) An experimental in-vivo canine model for adult shunt infection. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 5(17):1–7

Baveja JK, Willcox MDP, Hume EBH, Kumar N, Odell R, Poole-Warren LA (2004) Furanones as potential anti-bacterial coatings on biomaterials. Biomaterials 25:5003–5012

Bilginer B, Oguz KK, Akalan N (2009) Endoscopic third ventriculostomy for malfunction in previously shunted infants. Childs Nerv Syst 25:683–688

Cagavi F, Akalan N, Celik H, Gur D, Guciz B (2004) Effect of hydrophilic coating on microorganism colonization in silicone tubing. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 146:603–610

Cardia E, Molina D, Abbate F, Mastroeni P, Stassi G, Germanà GP, Germanò A (1995) Morphological modifications of the choroid plexus in a rodent model of acute ventriculitis induced by gram-negative liquoral sepsis. Possible implications in the pathophysiology of hypersecretory hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst 11(9):511–516

Dasic D, Liaquat I, Murphy M et al (2006) Antibiotic resistant infections with bactoseal catheters for VP shunts. Presented at the 148th Meeting of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons, London, UK

Dinçer A, Özek MM (2011) Radiologic evaluation of pediatric hydrocephalus. Childs Nerv Syst 27:1543–1562

Fichtner J, Güresir E, Seifert V, Raabe A (2009) Efficacy of silver-bearing external ventricular drainage catheters: a retrospective analysis. J Neurosurg 112(4):840–846

Galiano K, Pleifer C, Engelhardt K, Brossner G, Lackner P, Huck C, Lass-Florll C, Obwegeser A (2008) Silver segregation and bacterial growth of intraventricular catheters impregnated with silver nanoparticles in cerebrospinal fluid drainages. Neurol Res 30:285–287

Hazer B (2010) Amphiphilic poly (3-hydroxy alkanoate)s: potential candidates for medical applications. Energy and Power Engineering 31-38

Hazer DB, Hazer B (2011) The effect of gold clusters on the autoxidation of poly(3-hydroxy 10-undecenoate-co-3-hydroxy octanoate) and tissue response evaluation. J Poly Res 18(2):251–262

Hazer DB, Hazer B, Dinçer N (2011) Soft tissue response to the presence of polypropylene-g-poly(ethylene glycol) comb-type graft copolymers containing gold nanoparticles. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011:956169. doi:10.1155/2011/956169

Hiltunen R, Nieminen K, Takala T, Heiskanen E, Merikari M, Niemi K (2007) Low-weight polypropylene mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 110(2, Part 2):455–462

Huntterloher PR (1983) Hydrocephalus. In: Behrman RE, Vaughan VC, Nelson WE (eds) Nelson textbook of pediatrics, 12th edn. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 1566–1569

James HE, Walsh JW, Wilson HD et al (1980) prospective randomized study of therapy in cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection. Neurosurgery 7:459–463

Kalayci ÖA, Cömert FB, Hazer B, Atalay T, Cavicchi KA, Cakmak M (2010) Synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial activity of metal nanoparticles embedded into amphiphilic comb-type graft copolymers. Polym Bull 65:215–226

Khan OH, Enno TL, Del Bigio MR (2006) Brain damage in neonatal rats following kaolin induction of hydrocephalus. Exp Neurol 200:311–320

Kodo H, Hanada Y, İkeda M, Ohta K, Tamaki N (2000) Polypropylene mesh substitute for the fasial defect after using for the dural repair. Neurol Med Chir Tokyo 40:77–80

Koike Y, Cakmak M (2009) Atomic force microscopy observations on the structure development during uniaxial stretching of PP from partially molten state: effect of isotacticity. Macromolecules 37:2171–2181

Lee KH, Ohsawa O, Watanabe K, Kim IS, Givens SR, Chase B (2009) Electrospinning of syndiotactic polypropylene from a polymer solution at ambient temperatures. Macromolecules 42:5215–5218

Li X, Loh XJ, Li J (2005) Poly(ester urethane)s consisting of poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] and poly(ethylene glycol) as candidate biomaterials: characterization and mechanical property study. Biomacromolecules 6(5):2740–2747

McFadden JT (1972) Tissue reactions to standard neurosurgical metallic implants. J Neurosurgery 36:598–603

McGirt MJ, Leveque JC, Wellons JC III et al (2002) Cerebrospinal fluid shunt survival and etiology of failures: a seven-year institutional experience. Pediatr Neurosurg 36:248–255

McGirt MJ, Zaas A, Fuchs HE, George TM, Kaye K, Sexton DJ (2003) Risk factors for pediatric ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection and predictors of infectious pathogens. CID 36:858–862

Munson EL, Heard SO, Doern GV (2004) In vitro exposure of bacteria to antimicrobial impregnated-central venous catheters does not directly lead to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Chest 126:1628–1635

Park YS, Park SW, Suk JS, Nam TK (2011) Development of an acute obstructive hydrocephalus model in rats using N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Child Nerv Syst 27:903–910

Parker SL, Attenello FJ, Sciubba DM, Garces-Ambrossi GL et al (2009) Comparison of shunt infection incidence in high-risk subgroups receiving antibiotic-impregnated versus standard shunts. Child Nerv Syst 25:77–83

Pattavilakom A, Kotasnas D, Korman TM et al (2006) Duration of in vivo antimicrobial activity of antibiotic-impregnated cerebrospinal fluid catheters. Neurosurgery 58:930–935

Pedron S, Peinado C, Catalina F, Bosch P, Anseth KS, Abrusci C (2011) Combinatorial approach for fabrication of coatings to control bacterial adhesion. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed Aug 29. (Epub ahead of print)

Pfausler B, Beer R, Engelhardt K et al (2004) Cell index: a new parameter for the early diagnosis of ventriculostomy (external ventricular drainage)-related ventriculitis in patients with intraventricular hemorrhage? Acta Neurochir (Wien) 146:477–481

Piatt JH Jr, Carlson CV (1993) A search for determinants of cerebrospinal fluid shunt survival: retrospective analysis of a 14-year institutional experience. Pediatr Neurosurg 19:233–241

Quigley MR, Reigel DH, Kortyna R (1989) Cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections: report of 41 cases and a critical review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosci 15:111–120

Saldarriaga Fernández IC, Busscher HJ, Metzger SW, Grainger DW, van der Mei HC (2011) Competitive time- and density-dependent adhesion of Staphylococci and osteoblasts on crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol)-based polymer coatings in co-culture flow chambers. Biomaterials 32(4):979–984

Saldarriaga Fernández IC, Da Silva Domingues JF, van Kooten TG, Metzger S, Grainger DW, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC (2011) Macrophage response to staphylococcal biofilms on crosslinked poly(ethylene) glycol polymer coatings and common biomaterials in vitro. Eur Cell Mater 21:73–79, discussion 79

Scheidbach H, Tamme C, Tannapfel A, Lippert H, Köckerling F (2003) In vivo studies comparing the biocompatibility of various polypropylene meshes and their handling properties during endoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) patchplasty: an experimental study in pig. Surg Endosc 18(2):211–220

Secer Hİ, Kural C, Kaplan M, Kilic A, Düz B, Gonul E, İzci Y (2008) Comparison of the efficacies of antibiotic- impregnated and silver-impregnated ventricular catheters on the prevention of infections. an in vitro laboratory study. Pediatr Neurosurg 44:444–447

Stoiser B, Kofler J, Staudinger T et al (2002) Contamination of central venous catheters in immunocompromised patients: a comparison between two different types of central venous catheters. J Hosp Infect 50:202–206

von Holst H, Collins P, Steiner L (1981) Titanium, silver, and tantalum clips in brain tissue. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 56:239–242

Walters BC, Goumnerova L, Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB, Humphreys RP, Levinton C (1992) A randomized controlled trial of perioperative rifampin/ trimethoprim in cerebrospinal fluid shunt surgery. Childs Nerv Syst 8:253–257

Winn WC, Allen SD, Janda WM, Koneman EW, Procop GW, Schreckenberger PC, Woods GL (2006) Koneman’s color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology, 6th ed, introduction to microbiology. Part II: guidelines for collection, transport, processing, analysis, and reporting of cultures from specific specimen sources. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 105–107

Wong GKC, Poon WS, Ng SCP, Ip M (2008) The impact of ventricular catheter impregnated with antimicrobial agents on infections in patients with ventricular catheter: interim report. Acta Neurochir Suppl 102:53–55

Zabramski JM, Whiting D, Darouiche RO et al (2003) Efficacy of antimicrobial-impregnated external ventricular drain catheters: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Neurosurg 98:725–730

Zetterberg MM, Reijmar K, Pränting M, Engström A, Andersson DI, Edwards K (2011) PEG-stabilized lipid disks as carriers for amphiphilic antimicrobial peptides. J Control Release Aug 29. (Epub ahead of print)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hazer, D.B., Mut, M., Dinçer, N. et al. The efficacy of silver-embedded polypropylene-grafted polyethylene glycol-coated ventricular catheters on prevention of shunt catheter infection in rats. Childs Nerv Syst 28, 839–846 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-012-1729-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-012-1729-5