Abstract

Objects

This study was conducted to investigate the frequency and type of cutaneous stigmata in different forms of occult spinal dysraphism (OSD) and their correlation to the underlying malformation.

Methods

Fourteen different forms of spinal malformations were identified in 358 operated patients with OSD. Most frequent findings (isolated or in combinations) were spinal lipoma, split cord malformation, pathologic filum terminale, dermal sinus, meningocele manqué, myelocystocele and caudal regression. Stigmata were present in 86.3% of patients, often in various combinations. Using a binary logistic regression analysis, significant correlations with distinct malformations were found for subcutaneous lipomas, skin tags, vascular nevi, pori, hairy patches, hypertrichosis, meningoceles and “cigarette burn” marks.

Conclusions

Cutaneous markers in a high percentage accompany spinal malformations. Due to the correlations of different stigmata to distinct malformations, they can aid the clinician in further diagnostic and therapeutic work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term occult spinal dysraphism (OSD) summarizes a group of rare developmental disorders of the spinal canal and its contents, covered by a closed skin surface. The spinal malformations are often associated with specific skin lesions. The knowledge of these skin lesions can guide the clinician to underlying spinal pathology.

In this study, we describe the different types of these cutaneous markers. Their frequencies are analyzed in a cohort of 358 children with operatively confirmed OSD. In contrast to previous studies, special focus is laid on correlations of cutaneous markers with distinct intraspinal malformations.

Patients and methods

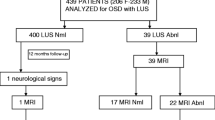

Data from all children with closed spinal dysraphism who underwent operation at the Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery in Würzburg (University of Würzburg) from 1985 to May 1999 were collected. Children with previous operations were excluded from the study, since the native appearance of the cutaneous lesion or the intraspinal findings cannot be assessed properly in these patients. Children with open spinal dysraphism were excluded as well. Based on these criteria, 358 children were enrolled in the study. Cutaneous stigmata were registered preoperatively with description of type and location of the lesion by the authors and partially documented by preoperative photographs.

The type of spinal malformation was classified according to preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and intraoperative findings in every patient.

Patients underwent operation at a mean age of 4.3 years (range, 1 day to 18 years).

Correlations between cutaneous signs and intraspinal malformations were statistically analyzed using binary logistic regression (SPSS statistic software).

Results

Spinal malformations

The following entities were identified among our patients in various combinations. Figures in brackets show the number of patients in whom a particular diagnosis was regarded as the main neurosurgical finding: spinal lipoma (188), split cord malformation (55), pathologic filum terminale (41), dermal sinus (27), meningocele manqué (ten), myelocystocele (eight), caudal regression (seven), spinal arachnoidal cyst (four), meningocele (four), atresia of spinal canal and myelon (four), ventral sacral meningocele (four), neurenteric cyst (three), primary tethered cord (two), dermoid (two). The total number of each malformation clearly exceeded these figures since many occurred in various combinations. Most frequent combinations were spinal lipoma or split cord malformation with pathologic filum terminale (28 and 43 cases, respectively); other relevant combinations are listed in Table 1.

Cutaneous lesions

The following 14 cutaneous abnormalities were differentiated in our patients:

-

(1)

Subcutaneous lipoma: localized additional subcutaneous fat tissue, presenting as soft “mass.” Lipomas can be localized in the midline or lateralized to one side (Figs. 1 and 2).

-

(2)

Skin tag: appendix of the skin, consisting of lipofibromatous tissue (Fig. 2).

-

(3)

Deviation of the gluteal fold.

-

(4)

Coccygeal pit: sacral dimple within the gluteal crease. The base of the dimple projects to the coccygeal tip (Fig. 3).

-

(5)

Atypical dimple: this term summarizes dimples found cranial to the gluteal crease or outside the midline, or dimples with a diameter >5 mm.

-

(6)

Porus: small, pointed opening on the skin surface. Some dark hairs may grow within the pit (Fig. 4). A porus does not project to the coccygeal tip.

-

(7)

Skin dysplasia: areas of atrophic or hyperkeratotic skin (Fig. 5).

-

(8)

“Cigarette burn” mark: small scarified area of abnormal skin (Fig. 6).

-

(9)

Cutaneous hemangioma: true hemangioma in or adjacent to the midline.

-

(10)

Vascular nevus: irregularly shaped, macular vascular lesion with smooth surface (port-wine-stain nevi). The reddish appearance completely blanches to diascopic pressure (Fig. 1).

-

(11)

Depigmented macula: area of hypopigmented skin (Fig. 2).

-

(12)

Hairy patch: circumscript and pronounced tuft of long hair, often in a triangular or rhomboid fashion (Fig. 7).

-

(13)

Hypertrichosis: diffuse and less pronounced increase in hairs in the lumbosacral area (Fig. 5).

-

(14)

Meningocele: visible and palpable fluid-filled masses. This “mass lesion” is, unlike lipomas, positive to diaphanoscopy (Fig. 8).

Cutaneous lesions were present in 309 of the 358 patients (86.3%). Single lesions were found in 115 patients, and combined lesions in 188 patients. Six patients had atypical stigmata not classified above, such as bony protuberance or an atypical “swelling” in the lumbosacral region.

Details and frequent combinations are summarized in Table 2. Eighteen children had coccygeal pits, but with only two of them as an isolated finding.

Correlation analysis

Using a binary logistic regression analysis, correlations between certain cutaneous stigmata and distinct intraspinal malformations can be identified. All malformations were included in this analysis, regardless of whether they were seen as the main surgical finding or not. Odds ratios and level of significance for relevant findings are presented in detail in Table 3. Statistical analysis was not feasible due to the limited number of cases for five spinal malformations (primary tethered cord, neurenteric cysts, atresia of spinal canal and myelon, ventral sacral meningocele, spinal arachnoidal cysts) and two skin markers (skin dysplasia, depigmented macula).

No cutaneous sign was found only in 11 out of a total of 188 patients with the main diagnosis of spinal lipoma, 11 of 41 patients with pathologic filum terminale, seven of 55 patients with split cord malformation, one of ten with meningocele manqué, none of the 27 patients with dermal sinus and none of the eight with myelocystocele, but in three out of three patients with neurenteric cysts, four out of four with isolated arachnoidal cysts, three out of seven with caudal regression, four out of four with spinal atresia, four out of four with ventral sacral meningocele and one out of two with an isolated dermoid.

Discussion

The term occult spinal dysraphism includes a variety of spinal malformations. These malformations are covered, per definition, by intact skin. Nevertheless, clinical presentation reveals cutaneous (or subcutaneous) markers in these patients, making the spinal malformation less “occult” than the term may suggest [5, 9, 19]. These signs are reported in about 50% and up to 100% of patients with OSD [7]. Our study confirms these high percentages of patients with cutaneous markers, at an overall percentage of 86%. Although these stigmata are well described in the literature, data are still limited. Characterization of the spinal malformation was difficult before the invention of MRI [17]. Surgical series often do not focus on this topic or include only one specific subtype of spinal malformation (e.g., lipoma), which excludes analysis of specific correlations between stigmata and different spinal lesions. On the other hand, population-based surveys of cutaneous stigmata and their correlation to spinal lesions lack a sufficient number of “true positive” patients due to the low incidence of OSD [11, 16].

In our series of 358 consecutive patients with OSD confirmed by MRI and intraoperative findings, ten types of spinal malformation were distinguished. Unlike some series [2, 17, 18], the largest subgroup consisted of children with spinal lipoma.

In all patients, a surgical “main” diagnosis could be made based on the leading intraspinal finding, but this abnormality was frequently combined with additional lesions. The cutaneous stigmata often occurred in combinations as well.

Statistical analysis of correlations between the respective skin marker and spinal lesion therefore was performed with binary logistic regression analysis. With this method, statistically significant correlations were found between the following cutaneous stigmata and spinal malformations.

Subcutaneous lipoma, a local surplus of differentiated fat cells, is a typical marker of spinal lipoma or lipomyelomeningocele [15], presenting as a homogeneously soft lump. This finding is confirmed by the correlation between these entities in our study. Frequently associated were skin tags, vascular nevi and deviations of the gluteal fold, which therefore also show statistically significant positive correlation with spinal lipoma. Another subcutaneous “mass lesion” detectable in the lumbosacral region is the fluctuating tumefaction of meningocele, which is associated with the intraspinal finding of a meningocele, naturally, but also correlated with a pathologic filum terminale.

Retractions of the skin can occur in the form of atypical dimples (vs coccygeal pits; see below) or small pori. Dimples were the third most frequent finding in our cohort, but were, to a large degree, associated with other skin lesions (Table 2). Hence, they are frequent findings in OSD [5], but not specific for the respective subtypes. Pori were present as the superficial opening of a dermal sinus in all cases, hence the strict correlation with high statistical significance is obvious between these two entities. Positive correlations also exist between dermal sinuses and vascular nevi or hypertrichosis. Since cutaneous markers were present in all these children, it should always be possible to identify a dermal sinus by inspection alone (thereby preventing meningitis and its sequelae).

An increased amount of hair can occur as diffuse hypertrichosis or a more circumscript tuft of hair (hairy patch). We statistically confirmed a high correlation of hairy patches with an underlying split cord malformation, as previously stated [9, 12, 14]. Diffuse hypertrichosis, on the other hand, was correlated with dermal sinuses, but not with split cord malformation.

In accordance with literature, the typical “cigarette-burn” mark, a small scarified area in the midline, is highly associated with meningocele manqué in our patients [8, 9]. It also shows weaker correlations with spinal lipoma and meningocele in our cohort.

Vascular lesions were differentiated in hemangiomas and vascular nevi (also referred to as “salmon patches,” “stork bite” or nevus flammeus simplex). Both are frequent findings in the neonate and regarded as harmless “birth marks” or possibly as a dermatological problem if they occur in various locations [10]. If located in the midline lumbosacral region, hemangiomas are regarded as indicators for OSD by some authors [1, 5, 9]. Although the role of vascular nevi is less unequivocal in the literature, this marker was also a relevant finding in our study [3–5]. Both stigmata are often associated with other cutaneous lesions. Unlike the more unspecific hemangiomas, vascular nevi showed correlations with spinal lipoma and dermal sinus in our cohort.

The above-mentioned cutaneous stigmata may indicate the presence of an underlying spinal malformation and should prompt further investigation. The type of malformation may be predicted by the clinician. Therefore, the timing and type of further diagnostic procedures can be adapted to the likely diagnosis (e.g., urgent diagnosis and treatment in dermal sinus to prevent meningitis vs elective MRI in neurological stable spinal lipoma). For other cutaneous signs and spinal malformations, no significant correlation was observed or could not be calculated because the numbers in these subgroups were too small.

Patients showing no cutaneous signs are rare with the more frequently occurring entities, whereas the rare spinal malformations, which are not of clear neuroectodermal origin (neurenteric cyst, isolated arachnoidal cyst, spinal atresia and ventral sacral meningocele), appear to occur typically without external marks.

Coccygeal pits were found in 18 of our subjects. Nevertheless, 16 carried additional diagnostic skin markers, and only two patients had isolated coccygeal pits. In neonates, the incidence of this skin lesion is 2–4% [16, 20]. Compared with the total number of 358 patients or 49 patients without cutaneous stigmata, respectively, these figures lie within the expected range for any cohort of children. This confirms the harmless nature of this lesion as an isolated finding, stated in previous studies [11, 20].

The data are limited insofar as these correlations are based only on patients with confirmed spinal malformation. We cannot calculate the predictive values of skin markers concerning spinal malformations, since the spinal malformation, and not the skin marker, was the inclusion criterion for our study. A study answering the reverse question is hardly possible, since OSD is very rare. Therefore, prospective studies concerning birthmarks fail to recruit a sufficient number of “true positive” patients [6, 16], which makes a prospective nature of a study concerning this topic nearly impossible. Limited data show, nevertheless, that these stigmata do carry a high risk, but are not inevitably combined with spinal malformation [11]. Since neurological sequelae can be prevented by early intervention, these markers should be known to the clinician in care of newborns and children [13].

The ectodermal origin of the neuroectodermal precursors in the contents of the spinal canal forms the embryologic basis for coincidental cutaneous and spinal malformations. Some correlations of cutaneous markers with spinal malformations, such as lipoma, meningocele or pori, are evident, while for others the reasons are still unclear.

In conclusion, our study confirms the association of certain skin markers with certain malformation entities of the spinal canal and myelon. For some of them, correlations with distinct forms of malformations exist. From a clinical point of view, the skin lesions described in this work should prompt further diagnostic work. These correlations can help clinicians weigh their diagnostic considerations.

References

Albright AL, Gartner JC, Wiener ES (1989) Lumbar cutaneous hemangiomas as indicators of tethered spinal cords. Pediatrics 83:977–980

Anderson FM (1975) Occult spinal dysraphism: a series of 73 cases. Pediatrics 55:826–835

Ben-Amitai D, Davidson S, Schwartz M, Prais D, Shamir R, Metzker A, Merlob P (2000) Sacral nevus flammeus simplex: the role of imaging. Pediatr Dermatol 17:469–471

Boyvat A, Yazar T, Ekmekci P, Gurgey E (2000) Lumbosacral vascular malformation: a hallmark for occult spinal dysraphism. Dermatology 201:374–376

Drolet BA (2000) Cutaneous signs of neural tube dysraphism. Pediatr Clin North Am 47:813–823

Gibson PJ, Britton J, Hall DM, Hill CR (1995) Lumbosacral skin markers and identification of occult spinal dysraphism in neonates. Acta Paediatr 84:208–209

Hall DE, Udvarhelyi GB, Altman J (1981) Lumbosacral skin lesions as markers of occult spinal dysraphism. JAMA 246:2606–2608

Higginbottom MC, Jones KL, James HE, Bruce DA, Schut L (1980) Aplasia cutis congenita: a cutaneous marker of occult spinal dysraphism. J Pediatr 96:687–689

Humphreys RP (1996) Clinical evaluation of cutaneous lesions of the back: spinal signatures that do not go away. Clin Neurosurg 43:175–187

Jacobs AH, Walton RG (1976) The incidence of birthmarks in the neonate. Pediatrics 58:218–222

Kriss VM, Desai NS (1998) Occult spinal dysraphism in neonates: assessment of high-risk cutaneous stigmata on sonography. Am J Roentgenol 171:1687–1192

Kumar R, Bansal KK, Chhabra DK (2001) Split cord malformation (scm) in paediatric patients: outcome of 19 cases. Neurol India 49:128–133

McLone DG, La Marca F (1997) The tethered spinal cord: diagnosis, significance, and management. Semin Pediatr Neurol 4:192–208

Pang D (1992) Split cord malformation. Part II: Clinical syndrome. Neurosurgery 31:481–500

Pierre-Kahn A, Zerah M, Renier D, Cinalli G, Sainte-Rose C, Lellouch-Tubiana A, Brunelle F, Le Merrer M, Giudicelli Y, Pichon J, Kleinknecht B, Nataf F (1997) Congenital lumbosacral lipomas. Childs Nerv Syst 13:298–334

Powell KR, Cherry JD, Hougen TJ, Blinderman EE, Dunn MC (1975) A prospective search for congenital dermal abnormalities of the craniospinal axis. J Pediatr 87:744–750

Scatliff JH, Kendall BE, Kingsley DP, Britton J, Grant DN, Hayward RD (1989) Closed spinal dysraphism: analysis of clinical, radiological, and surgical findings in 104 consecutive patients. Am J Roentgenol 152:1049–1057

Soonawala N, Overweg-Plandsoen WC, Brouwer OF (1999) Early clinical signs and symptoms in occult spinal dysraphism: a retrospective case study of 47 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 101:11–14

Tavafoghi V, Ghandchi A, Hambrick GWJ, Udverhelyi GB (1978) Cutaneous signs of spinal dysraphism. Report of a patient with a tail-like lipoma and review of 200 cases in the literature. Arch Dermatol 114:573–577

Weprin BE, Oakes WJ (2000) Coccygeal pits. Pediatrics 105:E69

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schropp, C., Sörensen, N., Collmann, H. et al. Cutaneous lesions in occult spinal dysraphism—correlation with intraspinal findings. Childs Nerv Syst 22, 125–131 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-1150-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-1150-4