Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the major risk factor for ischemic stroke, and oral anticoagulation is generally indicated for prevention of stroke. However, the utility of oral anticoagulation for AF in dialysis patients remains controversial. In this single-center, retrospective, observational study, data from 1120 patients on maintenance hemodialysis were analyzed. Baseline medical data were collected from dialysis records including age, gender, the cause of end-stage renal disease, dialysis vintage, and comorbidities. We evaluated outcomes including stroke, major hemorrhage, and death. A total of 106 (11.4 %) patients had AF. After exclusion criteria were applied, 84 patients had analyzable data. Warfarin was prescribed in 30 (35.7 %) of these patients. The remaining 54 patients were classified as the non-warfarin group. CHADS2 score was not significantly different between the warfarin and non-warfarin group. During the mean 47 months of follow up, 7 strokes occurred. However, warfarin use was not associated with the risk for stroke [hazard ratio (HR) 1.07; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.20–5.74]. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed no statistically significant difference in the overall survival, stroke-free survival or bleeding-free survival between the warfarin and non-warfarin group. AF is common in Japanese dialysis patients. Despite a certain prevalence of oral anticoagulation, the present study demonstrated neither beneficial nor detrimental effects. A large randomized controlled trial should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the major risk factor for ischemic stroke. Oral anticoagulation is generally indicated for prevention of stroke according to CHADS2 score, which is commonly used for stroke risk stratification for AF by assigning one point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, and diabetes, and two points for history of stroke/TIA [1]. However, the utility of oral anticoagulation for AF in hemodialysis patients remains controversial because mainly of a concern about bleeding complications [2]. Oral anticoagulation use may increase the risk of bleeding in dialysis patients, since they already receive anticoagulant therapy on routine dialysis. Furthermore, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is considered as one of the major risk factor for bleeding [3]. Another concern is about vascular calcification [4, 5]. Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, is generally used as oral anticoagulant therapy in patients undergoing hemodialysis. However, warfarin use has been reported to markedly increase vascular calcification, which may increase the risk for stroke [4]. This study was performed to investigate the impact of oral anticoagulation on outcome in Japanese patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis.

Materials and methods

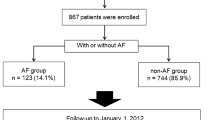

A retrospective, observational study based on medical records of 1120 maintenance hemodialysis patients was conducted at a Nippon Medical School Main Hospital or between June 1, 2003 and December 31, 2012. Inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥20 years with AF and end-stage renal disease requiring maintenance hemodialysis. Patients who were undergoing or underwent catheter ablation for AF were excluded from the outcome analysis. Patients with prosthetic heart valve, life expectancy <6 months, and patients without follow-up data were also excluded from the outcome analysis. For patients with more than one admission with an AF diagnosis, the date of the first admission was considered the initial date of entry into the study cohort. We calculated CHADS2 score, and assessed demographic characteristics and comorbidities, cause of end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular risk factors, medications, laboratory data, and dialysis vintage. The outcomes of interest were the first hospital admission for stroke, bleeding, and death from any cause. Transient ischemic attack (TIA) was not included as an endpoint. The clinical outcome was determined at the last follow-up visit. Telephone interviews were conducted for patients who were not followed at our institution. Written informed consent was obtained in all patients.

Statistical analysis

Measurements are presented as mean value ± SD. Comparisons of measurements between two groups were analyzed by Mann–Whitney U test. Fisher exact test was used for discrete variables. Survival rates, stroke free rates, and bleeding free rates in patients with and without warfarin were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the difference between them was compared using the log-rank test. The determination of prognostic significance of certain factors was explored by the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model analysis. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical calculations were performed with SPSS version 20 software (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 106 (11.4 %) patients had AF. Four patients who underwent catheter ablation for AF, 4 patients with a prosthetic heart valve, 2 patients with life expectancy <6 months, and 12 patients without follow-up data were excluded from the outcome analysis. After these exclusion criteria were applied, 84 patients had analyzable data. Warfarin was prescribed in 30 (35.7 %) of these patients. The remaining 54 patients were classified as the non-warfarin group. CHADS2 score was not significantly different between the warfarin and non-warfarin group (Table 1). During the mean 47 months of follow up, 7 strokes (one hemorrhagic stroke) and 4 bleedings including gastrointestinal bleeding (two), intracerebral hemorrhage (two) occurred, and 21 patients died. The comparison of each outcome is presented in Table 2. After adjusting for CHADS2 score, warfarin use was not associated with the risk for stroke [hazard ratio (HR) 1.07; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.20–5.74]. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed no statistically significant difference of the overall survival, stroke-free survival or bleeding-free survival between the warfarin and non-warfarin group (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that AF was detected as high as 11 % of the maintenance dialysis patients, suggesting AF is common in Japanese dialysis patients. This incidence rate is higher than that of the reported incidence (5.6 % in Japan) [6]. Although the reason of this difference is not clear, it could be due to patient selection or difference of age. Despite a certain prevalence of warfarin use (36 %), it was neither associated with stroke nor bleeding. To date, warfarin use in hemodialysis patients with AF remains controversial because previous studies showed conflicting results. A retrospective cohort analysis of 1671 maintenance hemodialysis patients with AF showed that warfarin use was associated with a significantly increased risk for stroke [7]. In addition, a prospective observational study using data from the international Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) demonstrated that warfarin use was associated with a significantly higher stroke risk, particularly in patients >75 years (n = 1107) [6]. Furthermore, recently conducted retrospective and prospective cohort studies of dialysis patients reported that warfarin use did not reduce the risk for ischemic stroke [2, 8]. The reason for increased rate of ischemic stroke could be explained by the fact that warfarin may promote vascular calcification, which can lead to atherosclerotic stroke [4, 5]. In addition, dialysis itself is associated with vascular calcification [9, 10].

On the other hand, one recent study came to the opposite conclusion: Olesen et al. demonstrated that warfarin use was associated with a significant decrease of stroke in 901 AF patients requiring renal-replacement therapy [11]. The study showed a 56 % reduction in the risk for the composite stroke/death outcome compared to those without anticoagulation therapy (HR 0.44; 95 % CI, 0.26–0.74). However, patients in the study receiving renal replacement therapy were younger (mean age: 66 years) with less comorbidities than the other studies of its kind. In addition, the study included not only hemodialysis patients but also renal transplant patients and peritoneal patients.

In Japan, a prospective study including 60 dialysis patients was conducted, which found that warfarin use was neither associated with a significant reduction in ischemic stroke events nor with significant increases in major bleeding or all-cause mortality [12]. This result is consistent with our study which demonstrated that warfarin use was not associated with subsequent risk of stroke. Although the reason of this result is not clear, it is speculated that warfarin might reduce cardioembolic stroke, but increase atherosclerotic stroke. Decrease of cardioembolic stroke may be offset by increase of atherosclerotic stroke, and the efficacy of warfarin use could be influenced by patient selection bias. Another possible explanation is poor prognosis of hemodialysis patients, which may obscure the efficacy of anticoagulant therapy. Actually, the 5-year survival rate for dialysis patients is 59.6 % in Japan [13]. This poor prognosis may limit the impact of anticoagulant therapy in this patient population.

With respect to bleeding tendency, dialysis patients have platelet dysfunction and impaired platelet-vessel wall interaction, which contribute to an increased risk for bleeding [14, 15]. As mentioned previously, dialysis patients already receive anticoagulant therapy on routine dialysis, which also increases the risk for bleeding. The preceding reports have suggested that warfarin therapy was associated with a higher risk for bleeding [2, 8]. Moreover, the risk of warfarin related intracranial hemorrhage was reported to be high in Asian population [15–17]. In fact, this study showed 2 of 30 patients in warfarin group developed subsequent intracranial hemorrhage, whereas none in non-warfarin group. However, warfarin use was not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of bleeding in the present study. This is probably owing to low rate of bleeding, which may be due to insufficiently controlled INR (1.62 ± 0.45) of the warfarin group. The concomitant use of antiplatelets and warfarin increases bleeding risks, and a large cohort study revealed that all combinations of warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel are associated with increased risk of fatal bleeding [18]. In the present study, the prevalence of antiplatelets use does not significantly differ between warfarin and non-warfarin group, and only two patients received triple therapy (warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel).

Taken together, the current predominant opinion is that routine warfarin therapy is not recommended for AF patients undergoing hemodialysis. The main advantage of this study is its long term follow up duration (mean 47 months), compared to previous studies.

Study limitations

There are several limitations in this study. First, our sample size was small, which can obscure the results of the present study. In addition, the beneficial effect of warfarin might be shown in patients with high CHADS2 score, but not with low CHADS2 score. Therefore it is supposed to divide the study patients according to CHADS2 score, but difficult because of small sample size of this study. Second limitation is the retrospective nature of this study. A large, multicenter, controlled, randomized trial is needed to assess the true efficacy of warfarin administration. The third limitation is that the study patients are from Japan, and there may be geographical differences that limit the broader applicability of the findings. The last limitation is that we checked PT-INR only once, so the quality of anticoagulation control with warfarin therapy could not be evaluated. Therefore no beneficial effect of warfarin for stroke may be related to insufficient dose of warfarin.

Conclusions

AF is common in Japanese dialysis patients. Despite a certain prevalence of oral anticoagulation, the present study demonstrated neither beneficial nor detrimental effects. A large multicenter-cooperative prospective cohort study is warranted, which may clarify the true efficacy of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in dialysis patients with AF.

References

Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ (2001) Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 285:2864–2870

Shah M, Avgil Tsadok M, Jackevicius CA, Essebag V, Eisenberg MJ, Rahme E, Humphries KH, Tu JV, Behlouli H, Guo H, Pilote L (2014) Warfarin use and the risk for stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing dialysis. Circulation 129:1196–1203

Friberg L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY (2012) Evaluation of risk stratification schemes for ischaemic stroke and bleeding in 182 678 patients with atrial fibrillation: the Swedish atrial fibrillation cohort study. Eur Heart J 33:1500–1510

Clase CM, Holden RM, Sood MM, Rigatto C, Moist LM, Thomson BK, Mann JF, Zimmerman DL (2012) Should patients with advanced chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation receive chronic anticoagulation? Nephrol Dial Transpl 27:3719–3724

McCabe KM, Booth SL, Fu X, Shobeiri N, Pang JJ, Adams MA, Holden RM (2013) Dietary vitamin K and therapeutic warfarin alter the susceptibility to vascular calcification in experimental chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 83:835–844

Wizemann V, Tong L, Satayathum S, Disney A, Akiba T, Fissell RB, Kerr PG, Young EW, Robinson BM (2010) Atrial fibrillation in hemodialysis patients: clinical features and associations with anticoagulant therapy. Kidney Int 77:1098–1106

Chan KE, Lazarus JM, Thadhani R, Hakim RM (2009) Warfarin use associates with increased risk for stroke in hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Nephrol 20:2223–2233

Genovesi S, Rossi E, Gallieni M, Stella A, Badiali F, Conte F, Pasquali S, Bertoli S, Ondei P, Bonforte G, Pozzi C, Rebora P, Valsecchi MG, Santoro A (2015) Warfarin use, mortality, bleeding and stroke in haemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Nephrol Dial Transpl 30:491–498

Inoue T, Ogawa T, Ishida H, Ando Y, Nitta K (2012) Aortic arch calcification evaluated on chest X-ray is a strong independent predictor of cardiovascular events in chronic hemodialysis patients. Heart Vessels 27:135–142

Takami Y, Tajima K (2014) Mitral annular calcification in patients undergoing aortic valve replacement for aortic valve stenosis. Heart Vessels. doi:10.1007/s00380-014-0585-511

Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, Hommel K, Kober L, Lane DA, Lindhardsen J, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C (2012) Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 367:625–635

Wakasugi M, Kazama JJ, Tokumoto A, Suzuki K, Kageyama S, Ohya K, Miura Y, Kawachi M, Takata T, Nagai M, Ohya M, Kutsuwada K, Okajima H, Ei I, Takahashi S, Narita I (2014) Association between warfarin use and incidence of ischemic stroke in Japanese hemodialysis patients with chronic sustained atrial fibrillation: a prospective cohort study. Clin Exp Nephrol 18:662–669

Nakai S, Hanafusa N, Masakane I, Taniguchi M, Hamano T, Shoji T, Hasegawa T, Itami N, Yamagata K, Shinoda T, Kazama JJ, Watanabe Y, Shigematsu T, Marubayashi S, Morita O, Wada A, Hashimoto S, Suzuki K, Nakamoto H, Kimata N, Wakai K, Fujii N, Ogata S, Tsuchida K, Nishi H, Iseki K, Tsubakihara Y (2014) Overview of regular dialysis treatment in Japan (as of 31 December 2012). Ther Apher Dial 18:535–602

Boccardo P, Remuzzi G, Galbusera M (2004) Platelet dysfunction in renal failure. Semin Thromb Hemost 30:579–589

Shen AY, Yao JF, Brar SS, Jorgensen MB, Chen W (2007) Racial/ethnic differences in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 50:309–315

Hart RG, Diener HC, Yang S, Connolly SJ, Wallentin L, Reilly PA, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S (2012) Intracranial hemorrhage in atrial fibrillation patients during anticoagulation with warfarin or dabigatran: the RE-LY trial. Stroke 43:1511–1517

Hankey GJ, Stevens SR, Piccini JP, Lokhnygina Y, Mahaffey KW, Halperin JL, Patel MR, Breithardt G, Singer DE, Becker RC, Berkowitz SD, Paolini JF, Nessel CC, Hacke W, Fox KA, Califf RM, ROCKET AF Steering Committee and Investigators (2014) Intracranial hemorrhage among patients with atrial fibrillation anticoagulated with warfarin or rivaroxaban: the rivaroxaban once daily, oral, direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation. Stroke 45:1304–1312

Hansen ML, Sørensen R, Clausen MT, Fog-Petersen ML, Raunsø J, Gadsbøll N, Gislason GH, Folke F, Andersen SS, Schramm TK, Abildstrøm SZ, Poulsen HE, Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C (2010) Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med 170:1433–1441

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yodogawa, K., Mii, A., Fukui, M. et al. Warfarin use and incidence of stroke in Japanese hemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Vessels 31, 1676–1680 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-015-0777-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-015-0777-7