Abstract

Background

There is limited information on the risks and benefits of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis.

Objective

The aim was to determine the risk of mortality, ischemic stroke, and bleeding associated with warfarin use in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis.

Patients and methods

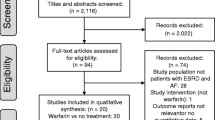

This is a retrospective observational study of a multi-ethnic cohort of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis in the United States. Using a dialysis registry, we identified 476 patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis. Among these patients, 115 (24%) were treated with warfarin. Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare risks of mortality, ischemic stroke and bleeding between the groups.

Results

Compared to untreated patients, patients receiving warfarin were older (67.3 ± 10.8 vs 62.9 ± 13.3 years) and more likely to be white (42% vs 31%). Prevalence of comorbidities including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, heart failure, and prior ischemic stroke were similar between the two groups. All cause mortality rates were 19.9 per 100 person-years in the warfarin group and 21.0 per 100 person-years in the untreated group. There was no difference between groups in the risk of mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.53–1.2, p = 0.28], ischemic stroke (HR 2.3, 95% CI 0.94–5.4, p = 0.07), hemorrhagic stroke (HR 2.0, 95% CI 0.32–12.8, p = 0.46), gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.39–2.2, p = 0.86), or any bleeding (HR 1.2, 95% 0.60–2.3, p = 0.65). Even in the subgroup of patients with > 70% time in therapeutic range, no association was seen between warfarin treatment and mortality.

Conclusion

There is no significant association between warfarin treatment with risks of mortality, ischemic stroke or bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is limited information on the risks and benefits of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis. |

We found no significant association between warfarin treatment and risks of mortality, ischemic stroke or bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis. |

Even in the subgroup of patients with > 70% time in therapeutic range, no association was seen between warfarin treatment and mortality. |

1 Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, with a prevalence of 2–3% in the general population [1]. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation is much higher in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on dialysis, ranging from 7 to 27%, with a prevalence of 13% and 7% in those on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, respectively [2,3,4]. Prior randomized clinical trials have shown anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation significantly reduces the risk for stroke [5]. However, patients on dialysis were excluded from these trials.

There are few observational studies looking at anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in those with ESRD receiving dialysis. However, these studies have found conflicting results regarding the risk and benefits of anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation [6,7,8,9]. As such, guideline recommendations have varied amongst different organizations [6, 10, 11]. In addition, the majority of these observational studies have focused on patients receiving hemodialysis or have combined both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis populations in the analysis and conclusions. To date, there is a paucity of data on the risks and benefits of anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the peritoneal dialysis population [12]. The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between warfarin use and the risk of all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Population

This was a retrospective, population-based cohort study that included all patients with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis in the Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) Health System between January 1, 2006 and September 30, 2015. KPSC is an integrated health care organization that serves about 4.4 million members. The demographics and socioeconomic status are representative of those living in California [13]. Patients who were not health plan enrollees or did not have continuous 1-year enrollment were excluded to allow adequate follow-up data. The research protocol in this study was reviewed and approved by the Kaiser Permanente Institutional Review Board.

Patients receiving peritoneal dialysis were identified using an internal dialysis registry maintained by the KPSC Health System. Patients with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter receiving peritoneal dialysis were identified using International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) codes 427.3, 427.31, and 427.32. The “index date” of study entry was when both criteria (“peritoneal dialysis” and “atrial fibrillation”) were met. Patients with less than 7 days of follow-up were excluded. Patients were followed for up to 2 years. Once entered into the study, patients were followed even if there was a change in dialysis status (from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis) to avoid bias that might result from the common practice of switching patients to temporary hemodialysis when they clinically deteriorate or become hemodynamically unstable. Baseline comorbidities were determined using ICD9-CM codes. CHA2DS2-VASc score was calculated by adding 1 point each for the presence of heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease, age 65–74 years, and female sex, and 2 points each for the presence of previous stroke/thromboembolism and age ≥ 75 years [14]. The HAS-BLED score was calculated by adding 1 point each for the presence of hypertension, abnormal renal or liver function, previous stroke/thromboembolism, history of bleeding, labile international normalized ratio (INR), age ≥ 65 years, concomitant therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and excessive alcohol intake [15].

2.2 Pharmacologic Treatment

Warfarin users were identified using pharmacy dispensing records if they filled at least one prescription for warfarin after their diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. All other patients were considered non-warfarin users. Use of other medications was determined by reviewing outpatient pharmacy dispensing records. The majority of warfarin users were enrolled in the anticoagulation clinic at KPSC. For these patients, INR was actively followed and warfarin dose titrated. An INR of 2.0–3.0 was considered to be within the therapeutic range. Time in therapeutic range (TTR) was calculated using the Rosendaal method [16]. A cutoff TTR of > 70% was chosen given prior studies showing maximum benefit at this level [17].

2.3 Outcomes

Information on mortality was obtained from the California vital statistics database and Kaiser Health Plan enrollment data. Outcomes including hospital admission or emergency room visit for a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, or other bleeds were identified using ICD9-CM and ICD10 codes.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Warfarin users and non-warfarin users were compared using independent samples t test and Chi square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. A two-tailed p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The association between warfarin use and the risk of all-cause mortality, stroke, and bleeding was determined using Cox proportional hazards models. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and analyzed by log-rank test. All analyses were performed using R version 3.3.3 [18].

3 Results

3.1 Patient Population

A total of 476 patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis were identified. Among this group, 115 patients were treated with warfarin and 361 were untreated. Compared to those not receiving warfarin, those given warfarin were older (67.3 ± 10.8 vs 62.9 ± 13.3 years, p = 0.001), more likely to be of white race (41.7% vs 31.3%, p = 0.039), and less likely to be of Hispanic race (21.7% vs 34.1%, p = 0.013) (Table 1). Those receiving warfarin were more likely to have a history of pulmonary embolism (PE) (8.7% vs 1.4%, p < 0.001). Otherwise there were no other significant differences in demographics or medical history.

Patients treated with warfarin were less likely to have used NSAIDs (18.3% vs 32.7%, p = 0.003) and more likely to have used beta-blockers (99.1% vs 90.9%, p = 0.003). There were no significant differences in medication usage of aspirin, P2Y12 inhibitors, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and statins. The CHA2DS2-VASc scores were not significantly different between groups (4.6 ± 1.6 vs 4.2 ± 1.8, p = 0.061). Patients on warfarin had a higher HAS-BLED score (4.6 ± 1.2 vs 4.0 ± 1.1, p < 0.001).

3.2 Survival Analysis

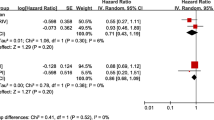

Median follow-up time was 1.5 years. During the 626.7 patient-years of follow-up, 32 patients in the warfarin group died (19.9 events per 100 patient-years; 95% confidence interval [CI] 13.0–26.9), whereas 98 patients in the non-warfarin group died (21.0 per 100 patient-years; 95% CI 16.9–25.2) (Table 2). The Kaplan–Meier survival estimate showed no significant difference in deaths in the warfarin versus non-warfarin group (log-rank test p = 0.807) (Fig. 1). Cox proportional hazards modeling showed no association between warfarin use and mortality, with an unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 0.95 (95% CI 0.64–1.42) and an adjusted HR of 0.80 (95% CI 0.53–1.20) (Table 3) after adjustment for age, male sex, white race, diabetes, congestive heart failure, history of ischemic stroke, history of gastrointestinal bleed, and aspirin use.

3.3 Stroke Outcome

The rate of ischemic stroke was higher in the warfarin group (6.2 per 100 person-years, 95% CI 2.4–10.1) compared to the non-warfarin group (2.4 per 100 person-years, 95% CI 1.0–3.8). The unadjusted HR for ischemic stroke on warfarin was 2.72 (95% CI 1.16–6.41, p = 0.022). After adjusting for potential confounders, there was no association between warfarin use and ischemic stroke, with an HR of 2.26 (95% CI 0.94–5.42, p = 0.07).

3.4 Bleeding Outcome

There was no significant difference in rates of hemorrhagic stroke, gastrointestinal bleed, or other bleed between both groups. The adjusted HR for hemorrhagic stroke was 2.0 (95% CI 0.32–12.8, p = 0.46). The adjusted HR for gastrointestinal bleed was 0.92 (95% CI 0.39–2.2, p = 0.855), and for any bleeding was 1.2 (95% CI 0.60–2.3, p = 0.65).

3.5 Time in Therapeutic Range on Warfarin

Among the 115 patients on warfarin, 108 (94%) were actively followed at the KPSC anticoagulation clinic and had serial INR values. Figure 2 shows the TTR between INRs of 2.0–3.0 in this patient population. The median TTR was 48% (25th percentile, 75th percentile: 31%, 66%). There were 55 patients (51%) with a TTR of < 50%, 36 (33%) with a TTR of 50–69%, and 17 (16%) with a TTR of > 70%. The HR for all-cause mortality (when adjusted for age, male sex, white race, diabetes, heart failure, history of ischemic stroke, history of gastrointestinal bleed, and aspirin usage) in those with a TTR of > 70% when compared to a TTR of < 70% was not statistically significant (HR 2.1, 95% CI 0.85–5.1, p = 0.107). This suggests that even in those patients that are most compliant with warfarin there was no benefit in mortality with warfarin usage.

4 Discussion

There are limited data on warfarin use for atrial fibrillation in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. In this study, we found no significant association in all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, and bleeding with warfarin use for atrial fibrillation in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. Subgroup analysis showed that even in patients with high TTR, no significant difference in mortality was observed. These findings may have implications when determining the risk-benefits of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis.

There are limited and conflicting data on warfarin use for atrial fibrillation in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis [8, 9]. A population-based retrospective cohort study of dialysis patients that included both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation found warfarin use to have no benefit in reducing stroke risk, but, rather, was associated with a higher bleeding risk compared to those not taking warfarin [8]. In contrast, another study of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving renal-replacement therapy (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) or living with a renal transplant found warfarin use to be associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality [9]. The only study that specifically focused on patients receiving peritoneal dialysis was an observational study of 271 Chinese patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis, which found warfarin use (n = 67, 24.7%) to be associated with lower risk of ischemic stroke without a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage [12].

Given the lack of data from randomized clinical trials, and conflicting results from limited observational studies, our goal is to present additional information from a relatively large contemporary cohort of peritoneal dialysis patients. Our study included 476 patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis. In this cohort, there was no association between warfarin use and all-cause mortality, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, or any bleeding after adjusting for potential confounders. We performed a sensitivity analysis evaluating the subgroup of patients with a TTR of > 70%, and found that even in the subgroup with good medication compliance, warfarin use was not associated with improvement in mortality.

A potential explanation for the lack of benefit of warfarin use in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis may be attributed to competing risk. In this cohort, the all-cause mortality rate is around 21 per 100 person-years, with many patients dying from causes other than stroke or bleeding. Sudden cardiac death accounts for over a quarter of all-cause mortality in dialysis patients [19], a risk warfarin therapy is not expected to modify. Others have suggested that warfarin may play a role in the pathogenesis of vascular calcification, which may negate the stroke reduction benefits seen with warfarin by reducing cardioembolic events [20].

There may be some differences in the benefits or outcomes seen with warfarin use in hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis populations. These differences may be related to various factors, such as (1) heparinization during hemodialysis, which may lead to increased bleeding, (2) decrease in coagulation inhibitors in hemodialysis patients which may lead to increased thrombotic risk, and (3) an overall inherent survival advantage seen in hemodialysis patients [21, 22]. Overall, our findings suggest that in the peritoneal dialysis population, warfarin use was not associated with significant improvement in mortality or ischemic stroke. Whether the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), which have a more favorable safety profile, have an advantage over warfarin in these patients is not known. Future studies, particularly randomized clinical trials, are needed before anticoagulation can be routinely recommended for treatment of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis.

This was a retrospective observational study and thus has several inherent limitations, such as confounders that may have not been accounted for. The sample size was limited, although this is the largest study to date of warfarin usage for atrial fibrillation in a pure peritoneal dialysis patient cohort. The median follow-up time was around 1.5 years, which is relatively short. Nevertheless, in other populations (non-peritoneal dialysis population), an effect on anticoagulation on clinical outcomes could be detected in this time frame, especially in high-risk populations such as ours where the event rates are high. Patients who did not have continuous 1-year enrollment to allow adequate follow-up data were excluded, which make these results most applicable to those with stable insurance coverage. Only clinically significant bleeding and stroke events that required hospital admissions or emergency room visits were included, and as such, occult bleeding events or silent ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes may have been missed. Furthermore, decision of warfarin therapy was based on the prescribing clinical provider at the time, and thus, possibly introducing selection bias. Nevertheless, given the lack of randomized clinical trials and the paucity of observational studies that address this question, our study provides valuable information that may help physicians and patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis make treatment decisions regarding warfarin use.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, there is no significant association between warfarin treatment and risks of mortality, ischemic stroke or bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving peritoneal dialysis.

References

Davis RC, Hobbs FD, Kenkre JE, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the general population and in high-risk groups: the ECHOES study. Europace. 2012;14(11):1553–9.

Zimmerman D, Sood MM, Rigatto C, Holden RM, Hiremath S, Clase CM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence, prevalence and outcomes of atrial fibrillation in patients on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2012;27(10):3816–22.

Genovesi S, Pogliani D, Faini A, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated factors in a population of long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(5):897–902.

Wetmore JB, Mahnken JD, Rigler SK, et al. The prevalence of and factors associated with chronic atrial fibrillation in Medicare/Medicaid-eligible dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2012;81(5):469–76.

Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):857–67.

Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893–962.

Winkelmayer WC, Liu J, Setoguchi S, Choudhry NK. Effectiveness and safety of warfarin initiation in older hemodialysis patients with incident atrial fibrillation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(11):2662–8.

Shah M, Avgil Tsadok M, Jackevicius CA, et al. Warfarin use and the risk for stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing dialysis. Circulation. 2014;129(11):1196–203.

Bonde AN, Lip GY, Kamper AL, et al. Net clinical benefit of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease: a nationwide observational cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23):2471–82.

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071–104.

Turakhia MP, Blankestijn PJ, Carrero JJ, et al. Chronic kidney disease and arrhythmias: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(24):2314–25.

Chan PH, Huang D, Yip PS, et al. Ischaemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Europace. 2016;18(5):665–71.

Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012;16(3):37–41.

Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(21):2719–47.

Olesen JB, Lip GY, Hansen PR, et al. Bleeding risk in ‘real world’ patients with atrial fibrillation: comparison of two established bleeding prediction schemes in a nationwide cohort. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(8):1460–7.

Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69(3):236–9.

Gallagher AM, Setakis E, Plumb JM, Clemens A, van Staa TP. Risks of stroke and mortality associated with suboptimal anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation patients. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106(5):968–77.

R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing [computer program]. Vienna, Austria. 2008.

Bleyer AJ, Hartman J, Brannon PC, Reeves-Daniel A, Satko SG, Russell G. Characteristics of sudden death in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69(12):2268–73.

Clase CM, Holden RM, Sood MM, et al. Should patients with advanced chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation receive chronic anticoagulation? Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2012;27(10):3719–24.

Bertoli SV, di Belgiojoso GB, Trezzi M, et al. Reduced blood levels of coagulation inhibitors in chronic hemodialysis compared with CAPD. Adv Perit Dial. 1995;11:127–30.

Yang F, Khin LW, Lau T, et al. Hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis: a comparison of survival outcomes in South-East Asian patients with end-stage renal disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140195.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Conflict of Interest

Derek Phan, MD, Su-Jau Yang, PhD, Albert Y.-J. Shen, MD, and Ming-Sum Lee, MD, PhD, have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phan, D., Yang, SJ., Shen, A.YJ. et al. Effect of Warfarin on Ischemic Stroke, Bleeding, and Mortality in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Receiving Peritoneal Dialysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 19, 509–515 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-019-00347-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-019-00347-3