Abstract

The purpose of this cross-sectional prospective study was to determine the prevalence of anemia among elderly hospitalized patients in Germany and to investigate its association with multidimensional loss of function (MLF). One hundred participants aged 70 years or older from two distinct wards (50 each from an emergency department and a medical ward, respectively) underwent a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) consisting of the following six tools: Barthel Index, mini-mental state examination, clock-drawing test, timed up and go test, Esslinger transfer scale, and Daniels test. MLF as an aggregated outcome was diagnosed when three or more tests of the CGA showed an abnormal result. Anemia was defined according to WHO criteria as a hemoglobin (Hb) concentration of <13 g/dL for men and <12 g/dL for women. The prevalence of anemia was 60 %. Overall, 61 % of patients presented with three or more abnormal results in the six tests of the CGA and, thus, with MLF. Using logistic regression, we found a significant association of both anemia and low Hb concentrations with abnormal outcomes in five tests of the CGA and, therefore, with domain-specific deficits like mobility limitations, impaired cognition, and dysphagia. Furthermore, being anemic increased the odds of featuring MLF more than fourfold. This significant relationship persisted after adjustment for various major comorbidities. Both anemia and geriatric conditions are common in the hospitalized elderly. Given the association of anemia with MLF, Hb level might serve as a useful geriatric screening marker to identify frail older people at risk for adverse outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, a whole new body of knowledge has been established concerning the prevalence of anemia in the elderly and its association with deficits across various specific domains. Several studies examined the frequency of anemia in community-dwelling elderly [1] and nursing home residents [2], but only a few studies dealt with hospitalized older people [3, 4]. There is a lack of German studies focusing on the anemic elderly in general, and consequently, to this day, no guidelines for this issue have been developed [5].

Multiple studies have shown a decline of functions in elderly patients in the course of a hospital stay [6, 7] from which some patients only recover very slowly [8] and which is associated with negative outcome [7, 9, 10]. Once recognized, these patients could benefit from specialized geriatric services taking care of their distinct needs [11]. This is why, facing a demographic change, the health ministry of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, in its newly issued hospital plan 2015 included a mandatory geriatric screening for all patients over 75 years of age upon admission to a hospital of this state.

To identify frail older patients at risk for adverse outcomes, such a screening should contain indicators of functional deterioration. We suspected anemia to be such an indicator of multidimensional loss of function (MLF) in the hospitalized elderly, as various studies were able to demonstrate strong associations of low hemoglobin (Hb) levels in older adults with deficits in specific domains [12–17]. While it still remains unclear if anemia acts as a triggering factor for functional decline or rather reflects other underlying disorders [18], the results from studies that demonstrated its association with a complex syndrome like frailty [19] suggest it to be an effective marker for a rather generalized decline in more than one distinct domain at the same time.

Hence, the main aim of this prospective study was to obtain insight into the association of anemia in the elderly with MLF as an aggregated outcome, detected through the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA). Additionally, by examining the prevalence of anemia among older patients in the hospital, we intended to determine the clinical relevance of low Hb levels as a geriatric problem in Germany.

Patients and methods

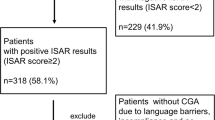

Study population

The present study comprised 100 patients aged 70 years or older who were recruited from two distinct wards of the university hospital of Cologne. Between November 2010 and July 2011, 50 subjects, each from an interdisciplinary monitoring unit attached to the central emergency department and a medical ward with a nephrological and general internal emphasis, respectively, were included. This division of our study population aimed at obtaining data of a more representative population. Research assistants visited the wards by no predefined pattern and then included a maximum of four patients per visit in order of admission, as time allowed. Inclusion criteria were the following: age, availability of a venous blood sample result including hemoglobin concentration collected during the current hospital stay, possibility of verbal communication with the patient or a proxy, and informed consent to participate by patient or legal guardian. Exclusion criteria were as follows: non-correctable visual or hearing impairment, severe pain, sedation, and clinical depression.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (file number 11-023 dated February 5, 2011) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Blood measurements

Standard determinations of serum hemoglobin were performed by the central laboratory of the university hospital, Cologne, using the analyzer Sysmex XE-5000 (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Laboratory results of the blood samples performed closest to the date of CGA were considered.

Definition of anemia

Anemia was defined according to the WHO criteria as Hb concentrations ≤12 g/dL for women and ≤13 g/dL for men [20] and was graded according to the degree of severity as mild (<12–11 g/dL in women and <13–11 g/dL in men), moderate (<11–8 g/dL), or severe (<8 g/dL) [21].

The comprehensive geriatric assessment and the definition of multidimensional loss of function

The CGA was performed by research assistants of the Department of Geriatrics who, in advance, had been trained in assessing older people. The CGA consisted of six tools, which covered the following domains: cognition, mobility, transfer skills, competence in performing the basal activities of daily living (bADLs), and swallowing ability. MLF as an aggregated outcome was diagnosed when three or more tests of the CGA showed an abnormal result. In the case of missing test results due to patient’s inability to perform the clock-drawing test (CDT) because of upper extremity limitations (three cases) or a medical contraindication to swallowing (Daniels test; one case), MLF was diagnosed clinically with due regard for the remaining test results and after consultation with a senior physician from the Department of Geriatrics of the University of Cologne.

The tools of the CGA

-

The Barthel Index (BI) assesses bADL disability [22]. We applied a rating scale from 0 (totally dependent) to 100 (maximal independence) [23]. Abnormal outcome was defined as 90 points or less.

-

The mini-mental state examination (MMSE) measures the global cognitive state [24, 25] with a rate ranging from 0 (severe cognitive impairment) to 30 (normal cognitive function). We regarded results of 27 points or less as abnormal [26].

-

The CDT covers cognitive domains only incompletely tested for by the MMSE, i.e., executive functions and visuospatial skills [27–29]. We used a scale from 1 (perfect) to 6 (no reasonable representation of a clock) [30]. A result of 3 or higher was rated abnormal.

-

The timed up and go (TUG) test was used to assess mobility status [31]. For methodical reasons, we created a rating scale with five ranks according to the time needed to finish the test: ≤15 s, 1; >15 to ≤25 s, 2; >25 to ≤35 s, 3; >35 s, 4; and TUG test not realizable, 5. Resulting ranks of 3 or higher were considered abnormal.

-

The Esslinger transfer scale (ETS) [32] refers to the degree of independence in changing position inside the bed and in transferring oneself from bed to chair, and it ranges from 0 (no assistance needed) to 4 (more than one professional assistant required). Ranks from 2 upwards were regarded as a functional limitation.

-

The Daniels test was utilized to detect dysphagia [33] and was rated abnormal (positive) or not.

Covariates

In order to adjust for possible confounding factors in the relationship of anemia and MLF, we collected information concerning 12 major comorbidities (presented in Table 1) directly from the patients and by studying their medical histories. Multimorbidity was defined as the non-specific presence of more than one major disease, while only renal and thyroid functions were assessed on the basis of laboratory results (serum creatinine concentration with a standard of 0.5–0.9 mg/dL in women and 0.5–1.1 mg/dL in men and thyroid-stimulating hormone with a standard of 0.27–4.20 mU/L respectively).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). To compare differences between groups, we used χ2 tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, respectively. To evaluate the association of Hb concentration, anemia, and its severity on the one hand with CGA test performance (dichotomized with regard to abnormal test result, yes/no) and the aggregated outcome “MLF” on the other hand, we conducted univariate logistic regression. In order to adjust for certain major comorbidities and age as confounding factors in the relationship of anemia and MLF, we initially performed bivariate correlations between these covariates and both anemia and MLF. Those covariates, which correlated significantly with either anemia or MLF, were included in a stepwise multivariate regression aiming at the exploration of an adjusted association of anemia with MLF, expressed by odds ratio.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

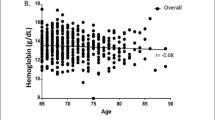

The mean age of the participants was 77.8 ± 5.7 years, and 55 % of the study population was female. Further sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are depicted in Table 1. We can note that our study population was characterized by high morbidity, especially concerning cardiovascular and nephrological diseases. More than 60 % of patients showed at least three abnormal results in the six tests of the CGA, defined as MLF. Deficits occurred primarily in the domains of ADL, demanding mobility and cognition (as assessed through Barthel Index, MMSE, and TUG test) with less limitations identified in the performances of basic transfer skills (ETS) and swallowing (Daniels test). We found a prevalence of anemia of 60 % and a mean Hb concentration of 11.5 g/dL. Anemic patients were more likely to have renal failure (p < 0.001), osteoporosis (p = 0.017), and hyperlipidemia (p = 0.018).

Group differences in Hb levels and anemia severity according to test outcome and MLF

Table 2 shows mean Hb differences according to patients’ functional outcomes. Participants with domain-specific deficits and MLF had lower Hb levels than those without, and these differences, with exception of CDT outcome, was statistically significant. Figure 1 shows test score differences across the degrees of anemia severity, whereas Fig. 2 illustrates the distribution of anemia severity categories with regard to the dichotomous outcomes of Daniels test results and MLF.

Impact of low Hb levels and anemia severity on domain-specific deficits and MLF

Using logistic regressions, we found significant associations of both low Hb levels and anemia severity according to the WHO classification system with, except CDT, all dichotomized test results and MLF. Table 2 depicts the odds ratios resulting from these regressions with regard to anemia severity categories. Similar results were found testing for Hb concentration as a numeric variable: for each drop of Hb concentration by 1 unit, there were 1.5-fold higher odds of MLF (CI = 1.19–1.92; p = 0.001).

Effects of anemia on domain-specific deficits and MLF

As can be perceived from Table 1, anemic participants performed worse in each of the six tests of the CGA, although differences in CDT performance were not significant. Consequently, anemia was also associated with MLF as the aggregated outcome of CGA. Including only those covariates that either correlated with anemia or MLF, we performed multiple logistic regression and found a significant influence of anemia and five other covariates on MLF (Table 3). Hospitalized patients with anemia had 4.3-fold greater odds for MLF than their non-anemic counterparts. Finally, the presence of hyperlipidemia was negatively associated with MLF (OR 0.12).

Discussion

In this hospital-based study of older patients, we found a high prevalence of both anemia and geriatric conditions. Moreover, low Hb levels were associated with worse outcomes in the tests of the CGA, and with multidimensional loss of function, the latter remains to be significant after adjustment for various major diseases. Against the backdrop of an aging society, these findings of both the high frequency of anemia among older hospitalized persons and its relationship with limitations across various domains point to a high relevance of low Hb level regarding the identification of elderly patients at risk for adverse outcomes in the course of their hospital stay.

We demonstrated anemia in 60 % of our patients, and these numbers exceeded the prevalence rates shown previously by two other hospital-based investigations: 44 % of 186 patients admitted to a geriatric unit of a Swiss University hospital had anemia [3], while Maraldi et al. found anemia to be prevalent in 46.8 % of geriatric and medical patients (≥65 years) upon hospital admission [4]. Rather, our results correspond with the anemia prevalence displayed in the setting of nursing homes [2, 34] where, by nature, multimorbidity is highly prevalent. Indeed, regarding the high anemia prevalence in our study population, a high burden of comorbidities must be taken into account. This is particularly noteworthy concerning the medical ward where severe renal and cardiovascular diseases were frequent.

The high prevalence of geriatric conditions in our study population is in line with other hospital-based works [35, 36], although assessment composition and cutoff values differed widely. Geriatric conditions detected by the CGA are not part of the traditional disease model, and there is the risk of overlooking them in the care of older hospitalized patients [37]. Not least because of this risk, new guidelines like the hospital plan 2015 have been established, and there is now a focus on recognizing elderly people who can benefit from geriatric services. Our results support the notion that there is a high percentage of older patients with distinct geriatric needs in German hospitals, and since comprehensively assessing elderly persons is time-consuming, the identification of risk factors as well as screening markers for functional decline might turn out to be crucial.

In our study, Hb concentration, anemia severity, and prevalent anemia all were significantly associated with the outcome in five tests of the CGA. Concerning the cognitive domain, only MMSE results were significantly related to anemia, whereas group differences of clock tests score lacked significance. Previous studies already found anemia to be associated with cognitive impairment in specific domains [38, 39], dementia [13], and delirium [40]. There are many possible mechanisms by which anemia can contribute to cognitive impairment ranging from a synergistic direct vascular effect with cardiovascular diseases [41, 42] to reduced neuroprotection in EPO deficiency in the elderly with CKD [13] or an indirect effect on cognitive function by negatively influencing physical fitness [18] and cardiac function [43]. Indeed, many subtle differences concerning the influence of low Hb levels on distinct cognitive domains still remain to be elucidated. These questions exceed the objective of our investigation and should be addressed by future studies.

Our results concerning the association between anemia and physical limitations as assessed by TUG test and ETS are in accordance with other works [14–16], and it comes as no surprise that such an association also translates into the domain of bADL performance. Again, there are various ways by which anemia can adversely affect physical capacities. Evans [44] points out to the close relationship of hemoglobin and VO2max with high Hb levels being paralleled by higher VO2max and, consequently, a higher submaximal exercise capacity. Another explanation is brought forward by Chaves [18]: since anemic older people often reduce their spontaneous physical activity levels, they lack a subjective negative sensation of fatigue. However, in the long term, this might lead to a further deconditioning with a reduction of the aerobic capacity as well as sarcopenia. Furthermore, results from the InCHIANTI study have demonstrated that anemia is associated with a loss of muscle mass as well as with structural changes of the muscle [16]. The authors postulate a direct effect of muscular hypoxia and, thus, a mechanism that is independent from weakness and fatigue.

We are not aware of any previous study that has examined the relationship between anemia and dysphagia. A mechanism explaining the association of low Hb levels with clinical symptoms of impaired swallowing in our study might include the already established relationship of anemia with dementia [13], which in turn represents a risk factor for dysphagia. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that there is a correlation between tongue and hand grip strength, supporting the notion that impaired oropharyngeal strength reflects sarcopenia as a global phenomenon [45]. Since Cesari et al. [16] have already postulated a direct effect of anemia on muscle strength and density, this association might serve as a further explanation for our findings.

Concerning the relationship of low Hb levels with bADL, our findings are in accordance with the results of previous studies [46–48]. Those works that failed to establish an independent significant association between anemia and the functional status in the elderly were predominantly population-based [49, 50]. This supports the notion that the deleterious effects of anemia on functional capacities might occur preferably in the frail elderly typically found in the hospital or nursing home.

MLF was the aggregated outcome of our study and diagnosed when three or more tests of the CGA resulted abnormal. The association between anemia and MLF remained significant after adjustment for age and major comorbidities in multivariate logistic regression. Results of the final analysis are depicted in Table 3; as can be seen, unsurprisingly, age and chronic progressive diseases with well-known multisystemic complications are significantly related to MLF, as is, albeit negatively, hyperlipidemia. So, in contrast to age and other comorbidities, abnormal high lipid levels significantly reduce the odds for MLF. This could be due to the already established link between low lipid levels in the elderly and frailty [51] as well as cognitive and physical deficits [52].

The association between anemia and MLF might result from a direct independent deteriorating effect of anemia on the performance across various domains. Since our study design was cross-sectional, we cannot account for the direction of the association. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility of anemia being a mere marker for a high burden of morbidity, since we adjusted only for few, albeit important diseases. Notwithstanding these doubts, our findings provide new evidence for the link between anemia and multidimensional loss of function. Since determination of Hb concentration is part of the standard laboratory test performed on admission and costs are relatively low, important requirements are thus fulfilled for an ideal screening parameter to identify those hospitalized elderly at risk for adverse outcomes.

Strengths of this study include the recruitment of a representative study population by selecting patients from two very different settings regarding the hospitalized elderly. Moreover, we performed CGA in a standardized manner, and the assessment consisted of validated tests.

Our study has limitations. Besides the shortcomings of a study with cross-sectional design, these include the small size of our study population. Furthermore, we were not able to record individual changes of test performance over the course of the hospital stay. Finally, further adjustment for inflammatory markers could have complemented the results and might have weakened the association between anemia and MLF.

Conclusion

Anemia and geriatric conditions are common problems in the hospitalized older adult. Our study demonstrates a significant association between anemia and multidimensional loss of function in the elderly inpatient. Since Hb concentration assessment is one of the most commonly performed laboratory tests in hospitalized patients, it might serve as a useful screening method to identify frail older people at the risk for adverse outcomes.

References

Beghé C, Wilson A, Ershler WB (2004) Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in geriatrics: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med 116(Suppl 7A):3S–10S

Landi F, Russo A, Danese P, Liperoti R, Barillaro C, Bernabei R, Onder G (2007) Anemia status, hemoglobin concentrations, and mortality in nursing home older residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 8(5):322–327

Mitrache C, Passweg JR, Libura J, Petrikkos L, Seiler WO, Gratwohl A, Stähelin HB, Tichelli A (2001) Anemia: an indicator for malnutrition in the elderly. Ann Hematol 80(5):295–298

Maraldi C, Volpato S, Cesari M, Cavalieri M, Onder G, Mangani I, Woodman RC, Fellin R, Pahor M (2006) Anemia and recovery from disability in activities of daily living in hospitalized older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(4):632–636

Röhrig G, Schulz RJ (2012) Anemia in the elderly. Urgent need for guidelines. Z Gerontol Geriatr 45(3):182–185

Boyd CM, Xue QL, Simpsons CF, Guralnik JM, Fried LP (2005) Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am J Med 118(11):1225–1231

Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, Burant CJ, Landefeld CS (2003) Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(4):451–458

Boyd CM, Ricks M, Fried LP, Guralnik JM, Xue QL, Xia J, Bandeen-Roche K (2009) Functional decline and recovery of activities of daily living in hospitalized, disabled older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Study I. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(10):1757–1766

Fortinsky RH, Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS (1999) Effects of functional status changes before and during hospitalization on nursing home admission of older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54(10):M521–M526

Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, Hughes JS, Horwitz RI, Concato J (1998) Importance of functional measure in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA 279(15):1187–1193

Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, Kowal J (1995) A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med 332(20):1338–1344

Shah RC, Wilson RS, Tang Y, Dong X, Murray A, Bennett DA (2009) Relation of hemoglobin to level of cognitive function in older persons. Neuroepidemiology 32(1):40–46

Hong CH, Falvey C, Harris TB, Simonsick EM, Satterfield S, Ferrucci L, Metti AL, Patel KV, Yaffe K (2013) Anemia and risk of dementia in older adults: findings from the Health ABC study. Neurology 81(6):528–533

Penninx BW, Pahor M, Cesari M, Corsi AM, Woodman RC, Bandinelli S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L (2004) Anemia is associated with disability and decreased physical performance and muscle strength. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(5):719–724

Chaves PH, Ashar B, Guralnik JM, Fried LP (2002) Looking at the relationship between hemoglobin concentration and prevalent mobility difficulty in older women. Should the criteria currently used to define anemia in older people be reevaluated? J Am Geriatr Soc 50(7):1257–1264

Cesari M, Penninx BW, Lauretani F, Russo CR, Carter C, Bandinelli S, Atkinson H, Onder G, Pahor M, Ferrucci L (2004) Hemoglobin levels and skeletal muscle: results from the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(3):249–254

Umegaki H, Yanagawa M, Endo H (2011) Association of lower hemoglobin level with depressive mood in elderly women at high risk of requiring care. Geriatr Gerontol Int 11(3):262–266

Chaves PH (2008) Functional outcomes of anemia in older adults. Semin Hematol 45(4):255–260

Artz AS (2008) Anemia and the frail elderly. Semin Hematol 45(4):261–266

Blanc B, Finch CA, Hallberg L et al (1968) Nutritional anaemias. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. WHO Tech Rep Ser 405:1–40

World Health Organization (2011) Institutional repository for information sharing: Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anemia and assessment of severity. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85839/3/WHO_NMH_NHD_MNM_11.1_eng.pdf. Accessed 24 Sept 2013

Collins C, Wade DT, Davies S, Horne V (1988) The Barthel ADL index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 10(2):61–63

Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft klinisch-geriatrischer Einrichtungen e.V. (2002). Hamburger Einstufungsmanual zum Barthel-Index. Version 1.0. Berlin: Bundesverband Geriatrie. http://www.bv-geriatrie.de/Dokumente/Hamburger%20Manual_11_2004.pdf. Accessed 24 Sept 2013

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental-state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198

Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ (1992) The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 40(9):922–935

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (2001) Mini-mental state examination user’s guide. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa

Hatfield CF, Dudas RB, Dening T (2009) Diagnostic tools for dementia. Maturitas 63(3):181–185

Connor DJ, Seward JD, Bauer JA, Golden KS, Salmon DP (2005) Performance of three clock scoring systems across different ranges of dementia severity. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 19(3):119–127

Brodaty H, Moore CM (1997) The clock drawing test for dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: a comparison of three scoring methods in a memory disorders clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 12(6):619–627

Shulman KI, Gold DP, Cohen CA, Zucchero CA (1993) Clock-drawing and dementia in the community: a longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 8:487–496

Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M (2000) Predicting the probability of falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther 80(9):896–903

Runge M, Rehfeld G (1995) Geriatrische Rehabilitation im Therapeutischen Team. Thieme, Stuttgart

Daniels SK, McAdam CP, Brailey K, Foundas AL (1997) Clinical assessment of swallowing and prediction of dysphagia severity. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 6:17–24

Robinson B, Artz AS, Culleton B, Critchlow C, Sciarra A, Audhya P (2007) Prevalence of anemia in the nursing home: contribution of chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(10):1566–1570

Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ (2008) Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Intern Med J 38(1):16–23

Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, Abu-Hanna A, Lagaay AM, Verhaar HJ, Schuurmans MJ, Levi M, de Rooij SE (2011) Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One 6(11):e26951

Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Tian Z, Blaum CS (2007) Geriatric conditions and disability: the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Intern Med 147(3):156–164

Lucca U, Tettamanti M, Mosconi P, Apolone G, Gandini F, Nobili A, Tallone MV, Detoma P, Giacomin A, Clerico M, Tempia P, Guala A (2008) Association of mild anemia with cognitive, functional, mood and quality of life outcomes in the elderly: the “health and anemia” study. PLoS One 3(4):e1929

Chaves PH, Carlson MC, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Semba R, Fried LP (2006) Association between mild anemia and executive function impairment in community-dwelling older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(9):1429–1435

Joosten E, Lemiengre J, Nelis T, Verbeke G, Milisen K (2006) Is anaemia a risk factor for delirium in an acute geriatric population? Gerontology 52(6):382–385

Inzitari M, Studenski S, Rosano C, Zakai NA, Longstreth WT Jr, Cushman M, Newman AB (2008) Anemia is associated with the progression of white matter disease in older adults with high blood pressure: the cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc 56(10):1867–1872

Abramson JL, Jurkovitz CT, Vaccarino V, Weintraub WS, McClellan W (2003) Chronic kidney disease, anemia, and incident stroke in a middle-aged, community-based population: the ARIC Study. Kidney Int 64(2):610–615

Metivier F, Marchais SJ, Guerin AP, Pannier B, London GM (2000) Pathophysiology of anaemia: focus on the heart and blood vessels. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15(Suppl 3):14–18

Evans WJ (2002) Physical function in men and women with cancer. Effects of anemia and conditioning. Oncology (Williston Park) 16(9 Suppl 10):109–115

Butler SG, Stuart A, Leng X, Wilhelm E, Rees C, Williamson J, Kritchevsky SB (2011) The relationship of aspiration status with tongue and handgrip strength in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66(4):452–458

Bang SM, Lee JO, Kim YJ, Lee KW, Lim S, Kim JH, Park YJ, Chin HJ, Kim KW, Jang HC, Lee JS (2013) Anemia and activities of daily living in the Korean urban elderly population: results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA). Ann Hematol 92(1):59–65

Bailey RA, Reardon G, Wasserman MR, McKenzie RS, Hord RS (2012) Association of anemia with worsened activities of daily living and health-related quality of life scores derived from the minimum data set in long-term care residents. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10:129

Terekeci HM, Kucukardali Y, Onem Y, Erikici AA, Kucukardali B, Sahan B, Sayan O, Celik S, Gulec M, Sanisoglu YS, Nalbant S, Top C, Oktenli C (2010) Relationship between anaemia and cognitive functions in elderly people. Eur J Intern Med 21(2):87–90

den Elzen WP, Willems JM, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J (2009) Effect of anemia and comorbidity on functional status and mortality in old age: results from the Leiden 85-plus Study. CMAJ 181(3–4):151–157

Ishine M, Wada T, Akamatsu K, Cruz MR, Sakagami T, Kita T, Matsubayashi K, Okumiya K (2005) No positive correlation between anemia and disability in older people in Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(4):733–734

Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, Tracy RP, Kop WJ, Hirsch CH, Gottdiener J, Fried LP (2002) Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation system with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 162(20):2333–2341

Ranieri P, Rozzini R, Franzoni S, Barbisoni P, Trabucchi M (1998) Serum cholesterol levels as a measure of frailty in elderly patients. Exp Aging Res 24(2):169–179

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zilinski, J., Zillmann, R., Becker, I. et al. Prevalence of anemia among elderly inpatients and its association with multidimensional loss of function. Ann Hematol 93, 1645–1654 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-014-2110-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-014-2110-4