Abstract

Endovascular stent placement and coil embolization have become established options in the treatment of visceral arterial aneurysms. In this article we report the case of an 83-year-old presenting with gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to a recurrent hepatic arterial aneurysm occurring 12 years after treatment with an endovascular stent. The recurrent aneurysm had resulted from stent fracture and was successfully treated by coil embolization. To our knowledge, stent fracture complicating the endovascular treatment of a visceral artery aneurysm has not been described in the published literature. With the increasing use of metallic endoprostheses in interventional radiology, recognizing and reporting device failure are of critical importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traditionally visceral arterial aneurysms were treated surgically. Endovascular treatment using coil embolization has become an established alternative. More recently, the utilization of endovascular stent-grafts to treat visceral artery aneurysms has emerged [1–5]. In this article we report the case of an 83-year-old presenting with gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to a recurrent common hepatic arterial aneurysm occurring 12 years after treatment with an endovascular stent. The recurrent aneurysm had resulted from stent fracture and was successfully treated by coil embolization. Visceral arterial aneurysm recurrence after endovascular treatment due to stent fracture has not been described in the published literature.

Case Report

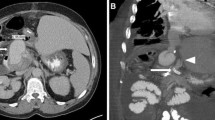

An 83-year-old presented following a collapse and was found to be anemic. Following normal upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy demonstrated transported blood in the colon. Having failed to identify the source of the gastrointestinal hemorrhage, an abdominal CT was performed. This study revealed a large hepatic arterial aneurysm surrounding a fractured endovascular stent (Fig. 1). At this point the history of a hepatic artery aneurysm treated with a covered endovascular stent 12 years previously became apparent. The decision was made to pursue endovascular treatment.

Arterial access was secured at the right common femoral artery using a 5-Fr sheath (Cordis). Superior mesenteric angiography and selective branch arteriograms were performed via a 5-Fr Cobra catheter (Terumo), demonstrating no active hemorrhage. Celiac arteriography confirmed a fractured stent within a large common hepatic artery (CHA) aneurysm, with stent fragments within the CHA proximal and distal to the aneurysm (Fig. 2). There was free flow of contrast within the aneurysm lumen and patent distal flow onward to the hepatic artery proper to supply the liver (Fig. 3). Collateral supply via the gastroduodenal artery distal to the aneurysm was confirmed. Given the anatomy, the decision was made to treat the recurrent aneurysm using embolization.

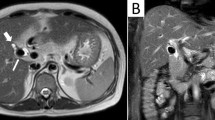

Friction within the fractured stent prevented access across the aneurysm to the distal CHA using the 5-Fr Cobra catheter. Exchanging this for a 5-Fr RVC catheter (Cook) allowed successful access and a 5 cm × 5-mm embolization coil (Cook) was deployed in the distal stent fragment. The configuration of the lumen of this fragment did not allow further coils to be placed, and during attempts to do this, a coil was lost into the aneurysm. As a single coil did not completely occlude distal CHA flow, a small volume of grated gelatin sponge (Johnson and Johnson) soaked in 5% ethanolamine oleate (Martindale Pharmaceuticals) was instilled to reinforce the occlusive effect. Having withdrawn the catheter into the proximal stent fragment, a 5 cm × 6-mm coil was deployed, again followed by a small volume of gelatin sponge. Postprocedure angiography demonstrated some residual aneurysm flow (Fig. 4). At this stage, the procedure was terminated, with the expectation that delayed occlusion of the embolized stent fragments would occur.

Arterial phase contrast-enhanced CT performed the next day confirmed successful aneurysm exclusion, with further resolution on a subsequent follow-up study (Fig. 5). Recovery was complicated by an episode of acute cholecystitis. However, at 1 year following the procedure the patient remains well.

Discussion

Visceral artery aneurysms are uncommon. However, they are being detected with increasing frequency due to the wider availability and utilization of cross-sectional imaging. Twenty percent of visceral artery aneurysms involve the hepatic artery [2]. Coil embolization is an established treatment in common hepatic artery aneurysm, with portal venous circulation and collateral flow from the gastroduodenal artery and its branches minimizing ischemic complications [2]. In the absence of adequate collateral supply, placing a covered stent across the aneurysm is an alternative that preserves flow to the liver.

Endovascular therapy is being increasingly utilized in the treatment of visceral artery aneurysms and is emerging as the treatment of choice in patients with associated comorbidities [6, 7]. Currently, there are no published data comparing the efficacy of stent-grafts and coil embolization in the treatment of visceral artery aneurysms. Decision-making regarding the endovascular therapeutic approach is largely based on the anatomy of the aneurysm. While this will always be the case, further studies examining the efficacy of these endovascular techniques would aid the interventionist in selecting a treatment strategy.

To our knowledge, stent fracture complicating the endovascular treatment of a visceral artery aneurysm has not been described in the published literature. With the increasing use of metallic endoprostheses in interventional radiology, recognizing and reporting device failure are of critical importance.

References

Jenssen GL, Wirsching J, Pedersen G, Amundsen SR, Aune S, Dregelid E, Joung T, Darapeyma A, Laxdal E (2007) Treatment of hepatic artery aneurysm by endovascular stent-grafting. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 30:523–525

Nosher JL, Chung J, Brevetti LS, Graham AM, Siegel RL (2006) Visceral and renal artery aneurysms: a pictorial essay on endovascular therapy. Radiographics 26:1687–1704

Rossi M, Rebonato A, Greco L, Citone M, David V (2008) Endovascular exclusion of visceral artery aneurysms with stent-grafts: technique and long term follow up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 31:36–42

Larson RA, Solomon J, Carpenter JP (2002) Stent graft repair of visceral artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 36(6):1260–1263

deFreitas D, Phade S, Stoner M, Bogey W, Powell CS, Parker F (2007) Endovascular stent exclusion of a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm. Vasc Endovascular Surg 41(2):161–164

Sachdev U, Baril DT, Ellozy SH, Lookstein RA, Silverberg D, Jacobs TS, Carroccio A, Teodorescu VJ, Marin ML (2006) Management of aneurysms involving branches of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries: a comparison of surgical and endovascular therapy. J Vasc Surg 44(4):718–724

Tulsyan N, Kashyap VS, Greenberg RK, Sarac TP, Clair DG, Pierce G, Ouriel K (2007) The endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg 45(2):276–283

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Downer, J., Choji, K. Late Recurrence of a Hepatic Artery Aneurysm After Treatment Using an Endovascular Stent. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 31, 1236–1238 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-008-9368-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-008-9368-7