Abstract

The most troublesome complications of inguinal hernia repair are recurrent herniation and chronic pain. A multitude of technological products dedicated to abdominal wall surgery, such as self-gripping mesh (SGM) and glue fixation (GF), were introduced in alternative to suture fixation (SF) in the attempt to lower the postoperative complication rates. We conducted an electronic systematic search using MEDLINE databases that compared postoperative pain and short- and long-term surgical complications after SGM or GF and SF in open inguinal hernia repair. Twenty-eight randomized controlled trials totaling 5495 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in this network meta-analysis. SGM and GF did not show better outcomes in either short- or long-term complications compared to SF. Patients in the SGM group showed significantly more pain at day 1 compared to those in the GF group (VAS score pain mean difference: − 5.2 Crl − 11.0; − 1.2). The relative risk (RR) of developing a surgical site infection (RR 0.83; Crl 0.50–1.32), hematoma (RR 1.9; Crl 0.35–11.2), and seroma (RR 1.81; Crl 0.54–6.53) was similar in SGM and GF groups. Both the SGM and GF had a significantly shorter operative time mean difference (1.70; Crl − 1.80; 5.3) compared to SF. Chronic pain and hernia recurrence did not statistically differ at 1 year (RR 0.63; Crl 0.36–1.12; RR 1.5; Crl 0.52–4.71, respectively) between SGM and GF. Methods of inguinal hernia repair are evolving, but there remains no superiority in terms of mesh fixation. Ultimately, patient’s preference and surgeon’s expertise should still lead the choice about the fixation method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recurrent herniation and postoperative pain are the main concerns that affect the quality of life of patients following inguinal hernia repair. Lichtenstein (1986) first described the concept of a tension-free repair with the use of a nonabsorbable mesh. This quickly became the gold standard for inguinal hernia repair [1]. With its adoption, recurrence rates and chronic postoperative pain improved, with recent reviews observing rates ranging between 1–2% and 6–29%, respectively [2, 3].

The “key” factors influencing hernia recurrence and postoperative pain have been the type of mesh used and the method of fixation [4,5,6]. There has been a considerable debate regarding this, with no international consensus to date.

Initially, Lichtenstein hernioplasty recommended polypropylene mesh placement with nonabsorbable stitch fixation [7]. However, in recent years there have been a multitude of technological products dedicated to abdominal wall surgery, such as self-gripping mesh (SGM), absorbable suture, and various biological and synthetic glues. They are postulated to reduce the incidence of postoperative complications [8].

The goal of this network meta-analysis was to compare pair-wise the trend of postoperative pain and the short- and long-term surgical complications of open inguinal hernia repair with SGM, suture fixation, and glue fixation (GF).

Materials and methods

Search strategy

A systematic review was performed according to the guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [9]. Institutional review board approval was not required for this type of study.

We conducted an electronic systematic search using MEDLINE databases (PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science). Last date of research was May 1, 2018. We searched for papers published in English using the following search strategy:

-

(“self-gripping mesh”[tiab] OR “ProGrip”[tiab]) AND (“sutured fixation”[tiab] OR “sutured mesh”[tiab]) AND (“open inguinal hernia “[tiab] “groin hernia” [tiab]) AND “clinical trial”[Publication Type]

-

(“self-gripping mesh”[tiab] OR “ProGrip”[tiab]) AND (“glue fixation”[tiab] OR “human fibrin sealant”[tiab] OR “Tissucol®”[tiab] OR “Tisseel®”[tiab]) AND (“open inguinal hernia “[tiab] “groin hernia” [tiab]) AND “clinical trial”[Publication Type]

-

(“glue fixation”[tiab] OR “human fibrin sealant”[tiab] OR “Tissucol®”[tiab] OR “Tisseel®”[tiab]) AND (“suture fixation”[tiab] OR “sutured mesh”[tiab]) AND (“open inguinal hernia “[tiab] “groin hernia” [tiab]) AND “clinical trial”[Publication Type]

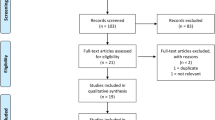

All titles were initially evaluated, and suitable abstracts were extracted. Besides, each of the eligible publication reference lists was also scanned for further potential articles (Fig. 1). The study protocol was registered and is accessible at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (registration number: CRD42018092224).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Only randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing the trend of postoperative pain and short- and long-term surgical outcomes after SGM versus SF or, SF versus GF, or SGM versus GF for open inguinal hernia repair were included in the analysis.

Studies were excluded from this analysis if: (a) articles were not in English; (b) methodology was not clearly reported; (c) details of surgical technique and surgical mesh/fixation method were not clearly reported (e.g., type of mesh and glue, absorbable/nonabsorbable suture); (d) the study did not have RCT design; (e) when more than one study reported the same patient cohort, only the study with longest follow-up or largest sample size was included.

Data extraction

The following data were retrieved from the selected publications: author, study year, country, study design, patients, gender, age, body mass index (BMI), type of hernia (site, direct, indirect, recurrent, size defect), operative time, and short- and long-term surgical outcomes (i.e., hematoma, seroma, pain, recurrences). All data were entered independently by two investigators (ER and AL) in two separate databases, which were compared only at the end of the reviewing process to reduce the selection bias. A third author (LB) finally reviewed the database. Duplicates were erased, and the discrepancies were clarified.

Study quality assessment

Two authors (ER and AL) independently assessed the methodological quality of the selected trials by using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool [10]. This tool evaluates the following criteria: (1) the method of randomization; (2) allocation concealment; (3) baseline comparability of study groups; and (4) blinding and completeness of follow-up. Trials were graded as follows: A, adequate; B, unclear; and C, inadequate on each criterion. Thus, each RCT was graded as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias (Figs. 2, 3). Disagreements were solved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

In addition to systematic review, we performed fully Bayesian arm-based random effect network meta-analysis, in particular mixed treatment comparison. Briefly, the network meta-analysis simultaneously synthesizes data from all available trials within a consistent network and combines direct evidence (comparison of treatments within head-to-head trials) with indirect evidence (comparison of treatments across trials against a common comparator) [11].

We preferred the Bayesian approach because that takes into account all sources of variation and reflects these variations in the pooled result. Furthermore, the Bayesian approach can provide more accurate estimates for small samples. An ordinary consistency model was adopted with the binomial/log model or normal/identity link function as likelihood for binomial outcomes and mean difference, respectively. Noninformative prior distributions included in this analysis were normal (0, 1000) distribution for log of relative risk (RR) and relative effects, and gamma (0.001, 0.001) distribution for random effect precision. Pair-wise comparison was made using unrelated mean effects model [12]. To assess transitivity, we generated descriptive statistics and compared the distributions of baseline participant characteristics across studies and treatment comparisons. To evaluate statistical heterogeneity, we calculated between-trial variances and I2-index, assuming a common estimate for the heterogeneity variance across the different comparisons. I2-index value of 25% was defined as low heterogeneity, 50% as moderate heterogeneity, and 75% as high heterogeneity [13]. To assess local inconsistencies, we used the node splitting method [14]. For continuous data, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were estimated from the median, range, and the size of the sample using validated techniques [15].

The inference was performed using mean and relative 95% credible intervals (Crl), based on draws from marginal posterior distribution in Monte Carlo Markov chain, simulating 350,000 iterations after a burn-in period of 30,000 iterations. We consider the estimated parameter significance when its 95% Crl encompass null hypothesis value. Sensitivity analysis regarding the choice of prior distribution of random effect precision was considered.

Model convergence was assessed by analyzing history, running means density, and Brooks–Gelman–Rubin diagnostic plots. In addition, autocorrelation plots were assessed to detect the presence of autocorrelation in the chains [16]. We plotted rank probabilities against the possible ranks for all competing treatments. All statistical analyses were performed using JAGS 4.3.0 [16] and R 3.4.3 [17].

Review of network geometry

We investigated the spectrum of comparisons among the different surgical techniques for open inguinal hernia within the network of published studies. We appraised the geometry of the networks for each outcome separately and provided network graphs with nodes reflecting the competing surgical approaches and two nodes linked together by an edge, if at least one study compared the two corresponding surgical techniques. We analyzed the connection between surgical approaches (i.e., those compared head-to-head in the selected studies and those which were only connected indirectly by one “common comparator” and the amount of evidence informing each comparison).

Outcomes of interest

The following outcomes were used to assess and compare open inguinal hernia repair with self-gripping mesh, sutured mesh, and glue fixation.

Primary outcomes Trends in postoperative pain according to a visual analog scale (VAS) (SGM and GF groups). The VAS score was standardized in a scale from 0 to 100 in order to homogenize the data. The VAS score trend was reported at the baseline, 1, 7, 30 days, and 1 year after surgery. Besides, we investigated recurrence rate and chronic pain at 1 year after surgery. Chronic pain was defined as persistent groin pain or any groin discomfort affecting daily activities that did not resolve by 3 months after surgery.

Secondary outcomes Operative time, short-term (within 30 days) postoperative complications (i.e., surgical site infection, seroma, and hematoma).

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

Five thousand five hundred thirty publications were found by using the aforementioned search criteria. After removing duplicates, 825 publications were further reviewed. Further screening found that 28 RCTs met the inclusion criteria [8, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Figure 1 depicts the selection process, and Fig. 4 depicts the studies reporting the primary outcomes.

Patient characteristics

Five thousand four hundred ninety-five patients were included in the selected studies; of these, 1373 (25%) were in the GF group, 1487 (27%) in the SGM group, and 2635 (49%) in the SF group, respectively. The mean age was 56.7 years. The gender was reported for 4776 patients, of which 4517 (94.5%) were males and 259 (5.4%) females. Body mass index (BMI) was investigated in 14 studies, and the median reported BMI was 25.5. The side of the inguinal hernia was reported in 2888 patients. It was left in 1258 (43.5%) patients and right in 1630 (56.5%) patients. The hernia characteristics were outlined in 4578 patients: 2881 (63%) was indirect and 1697 (37%) was direct. In 341 patients (9.3%) out of 3652, a combined type of hernia was described. Demographic data of all patients according to the surgical treatment are listed in Table 1.

Primary outcomes

The trend of postoperative pain according to VAS between SGM and GF

Pooled network analysis showed that the mean VAS scores at the baseline were 1.70 Crl − 4.80; 8.30. The global heterogeneity was 32.0%. The mean VAS scores at day 1 after surgery were statistically significant, − 5.2 Crl − 11.0; − 1.2. The global heterogeneity was 26.0%. The mean VAS scores at day 7 after operation were − 1.1 Crl − 6.3; 8.4. The global heterogeneity was 23.4%. The mean VAS scores at day 30 after operation were − 0.79 Crl − 5.4; 3.7. The global heterogeneity was 28.0%. The mean VAS scores at 1 year after surgery were − 1.4 Crl − 3.40; 0.80 (Fig. 5, and Supplementary Table 1). The global heterogeneity was 12.0%. The node splitting did not show evidence of lack of consistence.

Chronic pain

Pooled network analysis showed that the risk of chronic pain was similar among the three groups. The RR between SGM and GF was 0.63 (Crl 0.36; 1.12) and between SGM and SF was 1.1 (Crl 0.69; 1.60; Fig. 6a, and Supplementary Table 1). A rank plot illustrating empirical probabilities for overall complication in each surgical approach ranked 1st through 3rd (left to right) is depicted in Fig. 7a. The global heterogeneity was 17.58%. The node splitting did not show evidence of lack of consistence.

A rank plot created using the rankogram function from the gemtc R package applied to the three surgical approaches illustrating empirical probabilities that each treatment is ranked 1st through 3rd (left to right) for a chronic pain, b hernia recurrence, c operative time, d surgical site infection, e hematoma, and f seroma

Hernia recurrence

Pooled network analysis showed that the risk of hernia recurrence was similar among the three groups. The RR between SGM and GF was 1.5 (Crl 0.52; 4.70) and between SGM and SF was 0.65 (Crl 0.36; 1.20; Fig. 6b, and Supplementary Table 1). A rank plot illustrating empirical probabilities for overall complication in each surgical approach ranked 1st through 3rd (left to right) is depicted in Fig. 7b. The global heterogeneity was 0.00%. The node splitting did not show evidence of lack of consistence.

Secondary outcomes

Operative time

Pooled network analysis showed that the mean difference of operative time was similar between SGM and GF 1.70 (Crl − 1.80; 5.3). The operative times in both SGM and glue groups were significantly shorter compared to the SF group 7.7 (Crl 5.2: 10; Fig. 6c, and Supplementary Table 2). A rank plot illustrating empirical probabilities for overall complication in each surgical approach ranked 1st through 3rd (left to right) is depicted in Fig. 7c. The global heterogeneity was 90.0%. The node splitting did not show evidence of lack of consistence.

Surgical site infection

Pooled network analysis showed that the risk of surgical site infection was similar among the three groups. The RR between SGM and GF was 1.9 (Crl 0.35; 11.0) and between SGM and SF was 1.1 (Crl 0.60; 1.80; Fig. 6d, and Supplementary Table 2). A rank plot illustrating empirical probabilities for overall complication in each surgical approach ranked 1st through 3rd (left to right) is depicted in Fig. 7d. The global heterogeneity was 0.00%. It was not possible to conduct a formal assessment of consistency of the direct and indirect evidences as the evidence network only included unclosed loop.

Hematoma

Pooled network analysis showed that the risk of hematoma was similar among the three groups. The RR between SGM and GF was 0.83 (Crl 0.50; 1.30) and between SGM and SF was 1.0 (Crl 0.72; 1.40; Fig. 6e, and Supplementary Table 2). A rank plot illustrating empirical probabilities for overall complication in each surgical approach ranked 1st through 3rd (left to right) is depicted in Fig. 7e. The global heterogeneity was 0.00%. The node splitting did not show evidence of lack of consistence

Seroma

Pooled network analysis showed that the risk of seroma was similar among the three groups. The RR between SGM and GF was 1.80 (Crl 0.54; 6.50) and between SGM and SF was 1.0 (Crl 0.62; 1.50; Fig. 6f, and Supplementary Table 2). A rank plot illustrating empirical probabilities for overall complication in each surgical approach ranked 1st through 3rd (left to right) is depicted in Fig. 7f. The global heterogeneity was 0.00%. It was not possible to conduct a formal assessment of consistency of the direct and indirect evidences as the evidence network only included unclosed loop.

The sensitivity analysis regarding the choice of noninformative prior distribution or random effect precision showed the robustness of results.

Discussion

This is the first network meta-analysis to compare postoperative pain trends and complication rates between SGM and GF in open inguinal hernia repair. Our results show that the postoperative VAS score was significantly lower at day 1 in the GF group compared to SGM, while the pain score at day 7, day 30, and 1 year postoperatively was comparable. Operative times in both the SGM and GF groups were significantly shorter when compared to SF group. There was no statistical difference in complication rates (short or long term), chronic pain, or hernia recurrence between the three groups at 1 year after surgery.

This review highlights the heterogeneity in the surgical management of abdominal wall hernia. Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most common surgical procedures worldwide, with more than 20 million prosthetic meshes implanted annually [45]. As a result, there has been a considerable research performed to assess new technologies or techniques that may reduce incidence of complications and that have a positive effect on patient recovery. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in adapting less “traumatic” methods for mesh fixation. Similar to the findings of this review, several trials failed to show the advantages of newer fixation methods (i.e., SGM and GF) compared with traditional methods [8, 41].

Both SGM and GF have substantial cost implications, with SGM being 2.5 times more expensive than SF [23]. Cost analysis of GF is difficult, as there is a wide variation in products available, with limited published evidence to date [8]. A recent meta-analysis by Lin et al. [46] did not show any differences in surgical outcomes among these different glues. Though some postulated that the higher cost for SGM or GF may be offset by shorter operative times [23, 46], there are no data to conclusively show this. We did observe that the duration of inguinal hernia repair with no suture fixation was significantly shorter than with SF, but acknowledge that there are several cofounding factors that could also contribute to this, including operative skill, anesthetic time, and operative room schedules. We also acknowledge some limitations to this study, including the disparity in the current literature when reporting surgical and postoperative outcomes and comparing surgical techniques. In addition, there is heterogeneity in analgesia regimens across the studies, which may bias pain trends and variability in the methods to assess outcomes (i.e., telephone questionnaire, clinical examination, or ultrasound examination). The current review shows that there is no significant improvement with SGM or GF across the available literature. Its routine use would likely be associated with considerable cost implications, and ultimately, patient and surgeon preferences regarding operative technique should be paramount to ensuring a sound repair.

References

Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG (1986) Ambulatory outpatient hernia surgery. Including a new concept, introducing tension-free repair. Int Surg 71:1–4

Magnusson J, Gustafsson UO, Nygren J, et al (2018) Rates of and methods used at reoperation for recurrence after primary inguinal hernia repair with Prolene Hernia System and Lichtenstein. Hernia 22:439–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1705-9

Charalambous MP, Charalambous CP (2018) Incidence of chronic groin pain following open mesh inguinal hernia repair, and effect of elective division of the ilioinguinal nerve: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hernia 22:401–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1753-9

Pandanaboyana S, Mittapalli D, Rao A et al (2014) Meta-analysis of self-gripping mesh (Progrip) versus sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. Surgeon 12:87–93

Fang Z, Zhou J, Ren F et al (2014) Self-gripping mesh versus sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: system review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg 207:773–781

Sun P, Cheng X, Deng S et al (2017) Mesh fixation with glue versus suture for chronic pain and recurrence in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:Cd010814

Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK et al (1989) The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 157:188–193

Ronka K, Vironen J, Kossi J et al (2015) Randomized multicenter trial comparing glue fixation, self-gripping mesh, and suture fixation of mesh in Lichtenstein Hernia Repair (FinnMesh Study). Ann Surg 262:714–719 (discussion 719–720)

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC et al (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343:d5928

Mills EJ, Thorlund K, Ioannidis JP (2013) Demystifying trial networks and network meta-analysis. BMJ 346:f2914

Dias S, Sutton AJ, Ades AE et al (2013) Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Mak 33:607–617

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560

Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM et al (2010) Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 29:932–944

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I (2005) Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 5:13

Plummer M (2003) JAGS: a program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. In: Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop on distributed statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. 20–22 March 2003

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: [Accessed on 5 April 2018]. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/

Anadol AZ, Tezel E (2009) Prospective randomized comparison of conventional Lichtenstein versus self adhesive mesh repair for inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc 23:S315

Bruna Esteban M, Cantos Pallares M, Artigues Sanchez De Rojas E (2010) Use of adhesive mesh in hernioplasty compared to the conventional technique. Results of a randomised prospective study. Cir Esp 88:253–258

Chatzimavroudis G, Papaziogas B, Koutelidakis I et al (2014) Lichtenstein technique for inguinal hernia repair using polypropylene mesh fixed with sutures vs. self-fixating polypropylene mesh: a prospective randomized comparative study. Hernia 18:193–198

Fan JKM, Yip J, Foo DCC et al (2017) Randomized trial comparing self gripping semi re-absorbable mesh (PROGRIP) with polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernioplasty: the 6 years result. Hernia 21:9–16

Jorgensen LN, Sommer T, Assaadzadeh S et al (2013) Randomized clinical trial of self-gripping mesh versus sutured mesh for Lichtenstein hernia repair. Br J Surg 100:474–481

Kapischke M, Schulze H, Caliebe A (2010) Self-fixating mesh for the Lichtenstein procedure—a prestudy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395:317–322

Lionetti R, Neola B, Dilillo S et al (2012) Sutureless hernioplasty with light-weight mesh and fibrin glue versus Lichtenstein procedure: a comparison of outcomes focusing on chronic postoperative pain. Hernia 16:127–131

Molegraaf MJ, Grotenhuis B, Torensma B et al (2017) The HIPPO trial, a randomized double-blind trial comparing self-gripping Parietex Progrip mesh and sutured Parietex mesh in Lichtenstein Hernioplasty: a long-term follow-up study. Ann Surg 266:939–945

Nikkolo C, Vaasna T, Murruste M et al (2015) Single-center, single-blinded, randomized study of self-gripping versus sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. J Surg Res 194:77–82

Pierides G, Scheinin T, Remes V et al (2012) Randomized comparison of self-fixating and sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 99:630–636

Porrero JL, Castillo MJ, Perez-Zapata A et al (2015) Randomised clinical trial: conventional Lichtenstein vs. hernioplasty with self-adhesive mesh in bilateral inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia 19:765–770

Sanders DL, Nienhuijs S, Ziprin P et al (2014) Randomized clinical trial comparing self-gripping mesh with suture fixation of lightweight polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 101:1373–1382 (discussion 1382)

Verhagen T, Zwaans WA, Loos MJ et al (2016) Randomized clinical trial comparing self-gripping mesh with a standard polypropylene mesh for open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 103:812–818

Bracale U, Rovani M, Picardo A et al (2014) Beneficial effects of fibrin glue (Quixil) versus Lichtenstein conventional technique in inguinal hernia repair: a randomized clinical trial. Hernia 18:185–192

Campanelli G, Pascual MH, Hoeferlin A et al (2012) Randomized, controlled, blinded trial of Tisseel/Tissucol for mesh fixation in patients undergoing Lichtenstein technique for primary inguinal hernia repair: results of the TIMELI trial. Ann Surg 255:650–657

Dabrowiecki S, Pierscinski S, Szczesny W (2012) The Glubran 2 glue for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein’s hernia repair: a double-blind randomized study. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 7:96–104

Hidalgo M, Castillo MJ, Eymar JL et al (2005) Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty: sutures versus glue. Hernia 9:242–244

Hoyuela C, Juvany M, Carvajal F et al (2017) Randomized clinical trial of mesh fixation with glue or sutures for Lichtenstein hernia repair. Br J Surg 104:688–694

Jain SK, Vindal A (2009) Gelatin-resorcin-formalin (GRF) tissue glue as a novel technique for fixing prosthetic mesh in open hernia repair. Hernia 13:299–304

Karigoudar A, Gupta AK, Mukharjee S et al (2016) A Prospective randomized study comparing fibrin glue versus Prolene suture for mesh fixation in Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Indian J Surg 78:288–292

Kim-Fuchs C, Angst E, Vorburger S et al (2012) Prospective randomized trial comparing sutured with sutureless mesh fixation for Lichtenstein hernia repair: long-term results. Hernia 16:21–27

Moreno-Egea A (2014) Is it possible to eliminate sutures in open (Lichtenstein technique) and laparoscopic (totally extraperitoneal endoscopic) inguinal hernia repair? A randomized controlled trial with tissue adhesive (n-hexyl-alpha-cyanoacrylate). Surg Innov 21:590–599

Nowobilski W, Dobosz M, Wojciechowicz T et al (2004) Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty using butyl-2-cyanoacrylate versus sutures. Preliminary experience of a prospective randomized trial. Eur Surg Res 36:367–370

Paajanen H, Kossi J, Silvasti S et al (2011) Randomized clinical trial of tissue glue versus absorbable sutures for mesh fixation in local anaesthetic Lichtenstein hernia repair. Br J Surg 98:1245–1251

Shen YM, Sun WB, Chen J et al (2012) NBCA medical adhesive (n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) versus suture for patch fixation in Lichtenstein inguinal herniorrhaphy: a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 151:550–555

Testini M, Lissidini G, Poli E et al (2010) A single-surgeon randomized trial comparing sutures, N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and human fibrin glue for mesh fixation during primary inguinal hernia repair. Can J Surg 53:155–160

Wong JU, Leung TH, Huang CC et al (2011) Comparing chronic pain between fibrin sealant and suture fixation for bilayer polypropylene mesh inguinal hernioplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Surg 202:34–38

The HerniaSurge Group (2018) International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia 22:1–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1668-x

Lin H, Zhuang Z, Ma T et al (2018) A meta-analysis of randomized control trials assessing mesh fixation with glue versus suture in Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e0227

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rausa, E., Asti, E., Kelly, M.E. et al. Open Inguinal Hernia Repair: A Network Meta-analysis Comparing Self-Gripping Mesh, Suture Fixation, and Glue Fixation. World J Surg 43, 447–456 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4807-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4807-3