Abstract

Purpose

Groin hernia is one of the most common disease requiring surgical intervention (8–10% of the male population). Nowadays, the application of prosthetic materials (mesh) is the technique most widely used in hernia repair. Although they are simple and rapid to perform, and lower the risk of recurrence, these techniques may lead to complications. The aim of the present study is to assess the incidence and degree of chronic pain, as well as the impairment in daily life, in two procedures: (1) the “Lichtenstein technique” with polypropylene mesh fixed with non-absorbable suture, and (2) the “sutureless” technique carried out by using a partially absorbable mesh (light-weight mesh) fastened with fibrin glue.

Methods

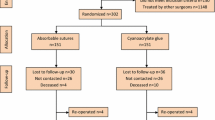

This was a study conducted over a period of 3 years from July 2006 to July 2009. A total of 148 consecutive male patients suffering from groin hernia were divided randomly into two groups: (1) Group A: patients operated with “sutureless” technique with partially absorbable mesh and plug fastened with 1 ml haemostatic sealant; (2) Group B: patients operated with Lichtenstein technique using non-absorbable mesh and plug anchored with polypropylene suture. Follow-up took place after 7 days, and 1, 6 and 12 months and consisted of examining and questioning patients about chronic pain as well as the amount of time required to return to their normal daily activities.

Results

No major complications or mortality were observed in either group. In group A there was a faster return to work and daily life activities. Six patients (7.8%) in group B suffered from chronic pain, whereas no patient in group A demonstrated this feature.

Conclusions

Our experience shows that the combined use of light-weight mesh and fibrin glue gives significantly better results in terms of postoperative pain and return to daily life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Groin hernia is one of the most common surgical diseases. The incidence in the general population is 5% but it rises to 8–10% if only the male population is considered [1]. Since Bassini and Shouldice first introduced their techniques, many types of surgical procedures have been developed over the last decades, leading in the end to the use of prosthetic materials (mesh) for wall reinforcement. Today these techniques have become widely used (80–90% of groin repairs) because they are simple and rapid to perform, and on account of the considerable decrease in recurrences over the years. Moreover, in many cases, interventions are performed in a day-surgery regimen, with reduced costs for the community and better tolerance for the patient. Although mesh repair has become almost routine practice [2], the use of prosthetic materials is not without complications, which are related mainly to the foreign body response to implanted materials or to the fixation of prosthesis with sutures. In fact, chronic inflammation following the implant of a mesh is proportional to the amount of non-absorbable material left in situ, and the sutures used to anchor the prosthesis may damage nerves or muscles. In both cases, this can lead to varying degrees of chronic groin pain after surgery [3]. This prospective, randomised study compares two different approaches to groin hernia repair: (1) the “Lichtenstein technique” requiring the use of polypropylene mesh, fixed by non-absorbable suture; and (2) the “sutureless” technique carried out by using a partially absorbable mesh (light-weight mesh) fastened with fibrin glue. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence and degree of chronic pain, as well as the impairment in daily life in both procedures.

Materials and methods

This study took place from July 2006 to July 2009. A total of 148 consecutive male patients, with a mean age of 55.7 years (age range, 18–82 years), suffering from groin hernia Nyhus II, IIIa, IIIb, P/L-M/1-3 according to European Hernia Society (EHS) classification [4], were considered. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. Frequently associated diseases were diabetes mellitus (9), COPD (8), coronaropathy (4).

Patients were divided randomly into two groups:

-

Group A: n = 72, patients operated with “sutureless” technique with partially absorbable mesh, fastened with fibrin glue.

-

Group B: n = 76, patients operated with Lichtenstein technique using non-absorbable mesh, anchored with non-absorbable suture.

The diagnosis was achieved through anamnesis, as well as clinical and ultrasound examination. All patients were fully briefed about the procedure and informed consent was obtained.

In Group A local anaesthesia with or without sedation was used in 39 cases, whereas spinal anaesthesia was applied in 33 cases.

In Group B local anaesthesia with or without sedation was performed on 42 patients, and spinal anaesthesia on 34 patients.

In both groups, local anaesthesia was achieved using 2% Mepivacaine Cloridrate + Sodium Bicarbonate for intradermal and subcutaneous infiltration and Ropivacaine 7.5 mg/ml for subfascial and hernia sac injection.

Antibiotic prophylaxis with ceftriaxone 2 g i.v. was administered approximately 1 h before anaesthesia.

In both groups particular attention was paid to:

-

Identification of the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and genito-femoral nerves.

-

Placement of a plug for Nyhus II and IIIb hernia.

-

Plication of transversalis fascia in case of Nyhus IIIa/b.

Two different prostheses were used according to the group the patients were assigned to.

In Group A, a partially absorbable mesh and plug of polypropylene and polyglecaprone 25 (Ultrapro® mesh: Ethicon), anchored with a concentrated solution of fibrinogen-fibrin (40–60 mg/ml), CaCl2 (5.6–6.2 mg/ml) for a total of 1 ml haemostatic sealant (Quixil®: Ethicon) was placed. Fibrin glue was applied with its dispenser first to the perimeter of the mesh, then to the entire surface of the prosthesis.

In Group B, a polypropylene mesh and plug (Prolene Mesh®: Ethicon) fastened with polypropylene suture was used according to the Lichtenstein technique.

In both groups the plication of the transversalis fascia was performed using absorbable thread (Vicryl® 2/0: Ethicon) so as to reduce the quantity of foreign material left in situ.

To evaluate pain 6, 12, and 24 h, and 7 days after surgery, all patients received a POP (post-operative pain) form based on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; Fig. 1). NSAID drugs were recommended for the treatment of pain.

Follow-up and clinical assessment took place after 7 days, and at 1, 6 and 12 months, and consisted of examining and questioning patients about possible complications, pain or discomfort, the amount of time required before they could return to their normal daily activities, as well as recurrence of preoperative symptoms.

Chronic pain was classified according to Cunningham’s [5] criteria as follows:

-

Mild: occasional pain or discomfort that did not limit activity, with a return to pre-hernia lifestyle

-

Moderate: pain preventing return to normal preoperative activities (inability to continue any sports or to lift objects without pain)

-

Severe: pain constantly or intermittently present but so severe as to impair normal activities, such as walking.

Statistical analysis

Data for numerical variables are summarized as mean ± SD. Data for categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. Acute pain VAS scores 6, 12, 24 h and 7 days after the intervention were analysed using repeated measure ANOVA with the patient group (A vs. B) as between-factor and the time as within-factor. Post hoc comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni-Dunn test. Operative time, return to daily life and return to work activity for working patients were analysed using Student’s t test for independent samples or using the Welch-corrected t test in case of heteroscedasticity. Recurrence and presence of chronic pain were analysed using the Fisher’s exact test. All tests were two sided and a P-value <0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

There was no intraoperative mortality in either group. Mean operative time was 44.4 ± 6.1 min in Group A (range 36–85) and 62.3 ± 9.2 min (range 48–103) in Group B (mean difference −17.9; P < 0.001; 95% CI −20.4 to −15.3).

One patient in Group A (1.4%) and three in Group B (3.9%) developed wound and scrotal haematoma but did not require any further treatment. There were a total of five cases of urinary retention (2 in Group A—6%; 3 in Group B—8.8%) in patients who underwent a spinal anaesthesia.

In Group A, the hospitalisation regimen was “day-surgery” in 30 cases (41.7%) and “1-day surgery” in 42 (58.3%). Day surgery was converted into 1-day surgery for two patients (6.7%) who received deep sedation.

In Group B, hospital stay was “day surgery” in 25 cases (32.9%) and “1-day surgery” in 51 (67.1%). Day surgery was converted into 1 day surgery in 2 patients (8%) who developed haematoma.

VAS scores are summarised in Table 2. The repeated measure ANOVA showed a significant main effect of group (P < 0.001), and time (P < 0.001) and a significant group-by-time interaction (P < 0.001). This interaction effect was due to a differential pattern of VAS score decrease between the two groups. Actually, in group A average VAS scores decreased almost linearly during the whole follow-up assessment with a statistically significant decrease observed for every two subsequent time points. In contrast, in group B the average VAS scores decreased significantly only from 12 to 24 h after the intervention. Average VAS scores were significantly lower in Group A than in Group B at all time points (P < 0.001).

Return to daily life and work activity was assessed for working patients (Group A 52/72; Group B 54/76). The mean time for return to daily activities was 4.4 ± 1.2 days (range 3–8) in Group A and 7.3 ± 1.8 days (range 5–10) in Group B (mean difference −2.8; P < 0.001; 95% CI −3.3 to −2.2). On average, patients were able to resume sedentary work in 7.4 ± 1.2 days (range 6–10) in Group A, and in 11.2 ± 1.6 days (range 7–13) in Group B (mean difference −3.8; P < 0.001; 95% CI −4.3 to −3.2).

After 6 months, 2 recurrences (1.3%) were recorded, one in each group (P > 0.05). In Group B, six patients (7.8%) suffered from chronic pain (P = 0.028) while no patients in Group A reported it. Pain was referred to as mild by three patients (4%), moderate by two (2.6%), severe by one (1.3%).

Discussion

Nowadays, mesh repair has become the gold standard for hernia repair, assuring excellent repair results and a low recurrence rate. According to the international literature, pain (both early and late onset) is an important and frequent complication of hernia surgery, causing varying degrees of discomfort to the patient. McGrath states that 30% of patients ascribe some degree of post-operative pain to discharge delay [6], while Alfieri reports that post-operative chronic pain is still present in 9.7% after 6 months and in 4.1% of cases after 1 year [7, 8].

Indeed, chronic postherniorrhaphy groin pain is defined as a persistent postoperative pain that fails to resolve 3 months after surgery, and can lead to depression and inability to work [8, 9].

A meta-analysis published in 2005 found that 12% of patients feel discomfort and restriction in daily activities due to the presence of pain [10]. POP is a consequence of both nerve damage and extensive scar tissue formation involving nervous structures, due to non-absorbable material left in situ. In the former case, the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal and genito-femoral nerves are mainly involved because they can be damaged during dissection or during use of the electric scalpel. Despite the primary role of the identification and preservation of these structures in hernia surgery, nerves can often be trapped into the non-absorbable sutures used to anchor prosthesis, and harmed by the subsequent inflammatory reaction.

In sutureless hernioplasty, the mesh is fastened with fibrin glue without using any stitches. A considerable body of literature supports the use of fibrin glue, proving its effectiveness, tolerability and lack of adverse effects [11–14]. In addition to haemostatic effects, fibrinogen components give tensile strength and adhesive properties, while thrombin promotes fibroblast proliferation [15]. In hernia surgery, fibrin glue has proved its effectiveness in preventing seromas, abscesses and haemorrhagic complications in patients with concurrent coagulation disorders [16]. Moreover, fibrin glue stimulates fibroblast activity, which results in a better and faster incorporation of the mesh material. Structural characteristics like the textile structure of the mesh are also important when fibrin glue is used. A large pore structure like Ultrapro® mesh with pore size of 3 mm permits a better growth of fibroblast through the porosity, although some authors report no differences in terms of promoting good tissue ingrowth [17–19]. Excellent results have been achieved in previous studies with the use of fibrin glue for fixation of mesh in laparoscopic extraperitoneal hernia repair [11, 20].

Chronic inflammation and foreign body reaction are other important factors causing POP in hernia surgery [21]. Despite being a biocompatible material, polypropylene is not absorbable. Recent studies have demonstrated that the inflammatory reaction following the foreign body reaction is directly proportional to the density of the mesh and the amount of foreign material left in situ. Following these considerations, recent years have seen the development of prostheses containing a smaller quantity of polypropylene in order to induce a lesser flogistic reaction. These so-called “light-weight meshes” provide excellent surgical repair with few long-term complications [22]. Moreover, the typical large porous textile structure guarantees an excellent resistance to intra-abdominal wall pressures, a lesser degree of shrinkage and better abdominal wall compliance [18].

In our experience, the combined use of light-weight mesh (Ultrapro®, Ethicon, http://www.ethicon.com/) and fibrin glue (Quixil®, Ethicon) works on the main factors that cause POP. Our results are encouraging. In “sutureless” repair, the incidence and degree of POP is significantly lower when compared to the Lichtenstein approach. Sutureless hernioplasty is quicker to perform, requiring a mean time of 44 min versus 62 min for Lichtenstein repair. In fact, fixation with fibrin glue is easier and quicker to perform than suture. In our experience, we routinely perform plication of transversalis fascia in Nyhus IIIa/b. In this way, by flattening the posterior wall of the inguinal canal the placement of the mesh becomes easier. The spermatic cord is placed under the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle, in direct contact with the prosthesis: from this point of view, in order to prevent related complications, it is obvious that a prosthesis eliciting a lower degree of flogistic reaction has to be preferred on account of the proximity of such critical structures.

The use of fibrin glue in hernia surgery has been criticised by some authors because of its high costs. Indeed, fibrin glue is a blood derivative product and, for this reason, production costs are still high. However, the higher costs can be justified by reduced hospital stay and operative time, quicker recovery of autonomy, and reduced chronic pain and other complications.

Conclusions

According to most recent studies [23], and our experience, sutureless hernia repair with light-weight mesh and fibrin glue is a promising approach to hernia surgery. In fact, it reduces operative time and hospital stay and allows excellent repair outcome with a lower rate of post-operative complications, such as post-operative pain, to be achieved. Nevertheless, we can only assess the effects of the combined use of fibrin glue and light-weight mesh, whereas it is not possible to evaluate their respective contributions to the attainment of our outcomes. Therefore, further research is ongoing.

The experiments comply with the current Italian laws.

References

Valenti G, Scaramuzza P, Testa A (1994) Le ernie inguinali: da Bassini al day Hospital. Ed. Utet, Torino. ISBN-13: 9788879330039

EU Hernia Trialist Collaboration (2000) Mesh compared with non-mesh methods of open groin hernia repair: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Surg 87(7):854–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01539

Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Müller M, Schumpelick V (1999) Foreign-body reaction to mesh used for the repair of abdominal wall hernias. Eur J Surg 165:665–673. doi:10.1080/11024159950189726

Miserez M, Alexandre JH, Campanelli G, Corcione F, Cuccurullo D, Pascual MH, Hoeferlin A, Kingsnorth AN, Mandala V, Palot JP, Schumpelick V, Simmermacher RK, Stoppa R, Flament JB (2007) The European hernia society groin hernia classification: simple and easy to remember. Hernia 11(2):113–116. doi:10.1007/s10029-007-0198-3

Cunningham J, Temple WJ, Mitchell P, Nixon JA, Preshaw RM, Hagen NA (1996) Cooperative hernia study. Pain in the postrepair patient. Ann Surg 224(5):598–602. doi:10.1097/00000658-199611000-00003

McGrath B, Elgendy H, Chung F, Kamming D, Curti B, King S (2004) Thirty percent of patients have moderate to severe pain 24 hr after ambulatory surgery: a survey of 5,703 patients. Can J Anaesth 51:886–891. doi:10.1007/BF03018885

Alfieri S, Rotondi F, Di Giorgio A, Fumagalli U, Salzano A, Di Miceli D, Ridolfini MP, Sgagari A, Doglietto G, Groin Pain Trial Group (2006) Influence of preservation versus division of ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and genital nerves during open mesh herniorrhaphy. Prospective multicentric study of chronic pain. Ann Surg 243:553–558. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000208435.40970.00

Fountain Y (2006) The chronic pain policy coalition. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 88:279. doi: 10.1308/147363506X144015

Malekpour F, Mirhashemi SH, Hajinasrolah E, Salehi N, Khoshkar A, Kolahi AA (2008) Ilioinguinal nerve excision in open mesh repair of inguinal hernia-results of a randomized clinical trial: simple solution for a difficult problem? Am J Surg 195:735–740. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.09.037

Aasvang E, Kehlet H (2005) Surgical management of chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 92:795–801. doi:10.1002/bjs.5103

Descottes B, Bagot d’Arc M (2009) Fibrin sealant in inguinal hernioplasty: an observational multicentre study in 1,201 patients. Hernia 13:505–510. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0524-z

Hidalg M, Castillo MJ, Eymar JL, Hidalg A (2005) Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty: sutures versus glue. Hernia 9:242–244. doi:10.1007/s10029-005-0334-x

Benizri EI, Rahili A, Avallone S, Balestro JC, Cai J, Benchimol D (2006) Open inguinal repair by plug and patch: the value of fibrin sealant fixation. Hernia 10:389–394. doi:10.1007/s10029-006-0112-4

Canonico S, Santoriello A, Campitiello F, Fattopace A, Corte AD, Sordelli I, Benevento R (2005) Mesh fixation with human fibrin glue (Tissucol) in open tension-free hernia repair: a preliminary report. Hernia 9: 330–333. doi:10.1007/s10029-005-0020-z

Campanelli G, Champault G, Hidalgo Pascual M, Hoeferlin A, Kingsnorth A, Rosenberg J, Miserez M (2008) Randomized, controlled, blinded trial of Tissucol/Tisseel for mesh fixation in patients undergoing Lichtenstein technique for primary inguinal hernia repair: rationale and study design of the TIMELI trial. Hernia 12:159–165. doi:10.1007/s10029-007-0315-3

Canonico S (2003) The use of human fibrin glue in the surgical operations. Acta Biomed 74(Suppl 2):21–25 PMID:15055028

Schug-Pass C, Lippert H, Köckerling F (2010) Mesh fixation with fibrin glue (Tissucol/Tisseel®) in hernia repair dependent on the mesh structure—is there an optimum fibrin–mesh combination? Investigations on a biomechanical model. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395:569–574. doi:10.1007/s00423-009-0466-z

Bellón JM, Rodríguez M, García-Honduvilla N, Pascual G, Buján J (2007) Partially absorbable meshes for hernia repair offer advantages over nonabsorbable meshes. Am J Surg 194:68–74. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.11.016

Holzheimer RG (2004) First results of Lichtenstein hernia repair with Ultrapro-mesh as cost saving procedure—quality control combined with a modified quality of life questionnaire (SF-36) in a series of ambulatory operated patients. Eur J Med Res 9:323–327 PMID:15257875

Olmi S, Addis A, Domeneghini C, Scaini A, Croce E (2007) Experimental comparison of type of Tissucol dilution and composite mesh (Parietex) for laparoscopic repair of groin and abdominal hernia: observational study conducted in a university laboratory. Hernia 11:211–215. doi:10.1007/s10029-007-0199-2

Kocijan R, Sandberg S, Chan YW, Hollinsky C (2010) Anatomical changes after inguinal hernia treatment: a reason for chronic pain and recurrence hernia? Surg Endosc 24:395–399. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0595-z

O’Dwyer PJ, Kingsnorth AN, Molloy RG, Small PK, Lammers B, Horeyseck G (2005) Randomized clinical trial assessing impact of a lightweight or heavyweight mesh on chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 92:166–170. doi:10.1002/bjs.4833

Negro P, Basile F, Brescia A, Buonanno GM, Campanelli G, Canonico S et al (2011) Open tension-free Lichtenstein repair of inguinal hernia: use of fibrin glue versus sutures for mesh fixation. Hernia 15:7–14. doi:10.1007/s10029-010-0706-8

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lionetti, R., Neola, B., Dilillo, S. et al. Sutureless hernioplasty with light-weight mesh and fibrin glue versus Lichtenstein procedure: a comparison of outcomes focusing on chronic postoperative pain. Hernia 16, 127–131 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0869-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0869-y