Abstract

Background

The knowledge of breast cancer risk factors and screening practices in a community is largely influenced by the practising gynaecologist in that area. We assessed the understanding and knowledge of gynaecologists about breast cancer: screening, risk factors, clinical signs, management and common benign breast diseases.

Methodology

This cross-sectional study was carried out in Uttar Pradesh, India, from April to September 2017. One hundred and fifty-two gynaecologists were assessed using a self-designed and validated questionnaire to assess the knowledge of risk factors, clinical signs, screening practices and management of breast cancer as well as common benign breast diseases. Further, the results were compared based on their education: undergraduates (UGs; no residency experience in obstetrics and gynaecology) versus postgraduates (PGs; residency experience in obstetrics and gynaecology).

Results

67 and 82.2% of gynaecologists possess excellent to very good knowledge of risk factors and clinical signs of breast cancer, respectively. The knowledge of PGs seems to be better than UGs (p < 0.01). 84.9% participants were aware that breast cancer screening decreases breast cancer-related mortality, and 61.2% considered CBE as most relevant screening investigation (66.1% PGs and 41.9% UGs; p = 0.04). 30.2% regularly offer breast cancer screening at their centre. 58.5% did not consider screening mammography as cost-effective for their patients (57.9% PGs and 61.3% UGs; p = 0.72), and 41.4% considered it to be a time-consuming process (39.7% PGs and 48.4% UGs; p = 0.38). 99.3% like to follow up a patient with familial breast cancer by themselves, and 0.7% like to refer them to specialist. 51.9% gynaecologists were convinced of breast conservation surgery (BCS) as a surgical option, however 51.3% feared leaving diseased breast behind.

Conclusion

Despite the knowledge regarding risk factors, clinical signs and treatment of breast cancer and benign breast diseases was found adequate amongst the gynaecologists, this did not apply to their clinical practice. Structured and continuous training of gynaecologists is needed to improve the outcome of patients with breast diseases in terms of better management and reference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

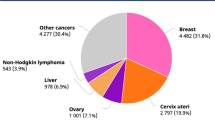

Breast cancer (BC) is most common cancer in women worldwide with an estimated 1.67 million new cancer cases diagnosed per year (25% of all cancers in women) [1]. It is the most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths amongst women in developing countries (324,000 deaths, 14.3% of total) [1].

India is experiencing an unprecedented rise in the number of BC cases across all sections of society with late stage of presentation a common feature [2]. Deaths due to BC are preventable if diagnosed at earlier stages. Regular breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE) and mammography [3] are various screening modalities.

Breast cancer knowledge assessment studies conducted amongst women in India reported low level of awareness of risk factors and screening practices [4, 5]. Health care providers, educational institutions and media are the important sources of educating women about breast cancer and motivating screening practices.

Adoption of screening methods for breast cancer in a community is largely influenced by knowledge and attitudes of health care providers [6, 7]. Health care workers, obstetricians and gynaecologists comprise most relevant group for this purpose as women in our part of country are usually comfortable consulting a lady doctor for breast diseases [8, 9]. Therefore, there is a need to assess the level of knowledge of common breast diseases and breast cancer risk factors in them. This would in turn help in developing medical education programmes to improve the knowledge of breast disease and adoption of various screening measures amongst this group of health care providers. The aim of this study is to assess the knowledge of benign breast diseases and breast cancer risk factors, screening practices and beliefs about treatment in the practising obstetricians and gynaecologists.

Methodology

Materials and methods

After obtaining ethics committee approval (KGMU ethics committee ref code: 84th ECM IIB-Fellowship/P5), this questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey was conducted from April to September 2017 (6 months) amongst the doctors practising gynaecology and obstetrics in urban parts of Uttar Pradesh. Decision to participate was voluntary and optional. 184 gynaecologists chose to participate, and 32 did not complete/partially complete the questionnaire and hence were excluded from the study. The participants were contacted through e-mails, online Web links (www.surveymonkey.com) and paper prints.

Measurements

A self-administered and validated questionnaire prepared by the authors was employed. Some questions were drawn from the literature on breast, and some were modified from questionnaires of similar studies. The questionnaire was divided into six parts: first part of the questionnaire elicited socio-demographic details based on age, gender, education qualifications, association with educational institution, the number of patients with breast-related problems seen per week. Second part included questions on benign breast diseases such as fibroadenoma. Questions related to risk factors and clinical signs of breast cancer were included in third and fourth parts, respectively. Questions related to risk factors [hormone replacement therapy (HRT), oral contraceptive pills (OCP), smoking, alcohol, family history, nulliparity, breastfeeding, male gender, fibroadenoma] and clinical signs (mobile mass, fixed mass, non-lactating galactorrhoea, bloody discharge from single duct, discharge from multiple ducts, peau d’orange, nipple pruritus ± excoriation, breast pain) were used to generate answers in yes/no format. In fifth part questions were asked about their opinion and practices related to breast cancer screening practices (BSE, CBE and mammography). The last (sixth) part included questions related to treatment of breast cancer.

Analysis

Each participating doctor was scored based on the knowledge of risk factors (n = 10) and clinical signs (n = 9) of breast cancer. Score in percentage of each participant was calculated. A score >80% was taken as “excellent” knowledge, 60–80% as “very good”, 40–60% as “good”, <40% as “poor” [10]. Further, the knowledge of doctors with no residency experience in obstetrics and gynaecology [undergraduates (UGs)] and those who completed their residency [postgraduates (PGs)] in obstetrics and gynaecology was compared. Data were analysed using SPSS-24 software (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Chi-square test was applied. p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Socio-demographic details

Table 1 summarises socio-demographic details of the gynaecologists. 184 gynaecologists participated in the study, and 152 (82.6%) completed survey. 59.3% gynaecologists had been practising for >15 years. 121 (79.6%) had completed their residency (postgraduation) in obstetrics and gynaecology, and 31 (20.4%) had no residency experience in obstetrics and gynaecology (undergraduates). 32.2% participants had affiliation to a teaching institute. 85 (55.9%) had attended workshops and/or seminars on breast diseases. 36 (23.7%) had exposure to a family member with breast cancer. The average number of breast patients attended by each gynaecologist was 9/week (range 3–75 patients/week).

Perception of benign breast diseases

Table 2 summarises participants’ knowledge about benign breast diseases. 130 (85.5%) participants were aware that fibroadenoma is common in young patients. 71.1% chose to biopsy fibroadenoma. For smaller fibroadenomas 62.5% chose to follow up small fibroadenomas, while 29.6% chose medical treatment. 66.5% participants chose surgical excision for large fibroadenomas (>2 cm).

Risk factors for developing breast cancer

Tables 3 and 4 summarise the knowledge of participants on risk factors for breast cancer. 26.3% had excellent knowledge of risk factors, 40.7% had very good knowledge, and 19.2% had good knowledge, while 13.8% had poor knowledge. Comparing the knowledge in PGs versus UGs, 28.9% PGs possessed excellent knowledge and 44.6% had very good knowledge of risk factors, while 16.2% UGs had excellent knowledge and 25.8% had very good knowledge (p = 0.007). The most commonly known risk factor was positive family history of breast cancer (88.2%). 19.1% PGs and 41.9% UGs were not aware that male population can also develop breast cancer (p = 0.007). 32.2% PGs and 51.6% UGs considered fibroadenoma as a risk factor for cancer (p = 0.04).

Clinical signs of breast cancer

Tables 5 and 6 summarise the knowledge of participants about clinical signs of breast cancer. Overall, 23.6% participants had excellent knowledge, 58.6% had very good knowledge, 8.6% participants had good knowledge and 9.2% participants had poor knowledge about clinical signs of breast cancer. On comparison, 28.1% of PGs versus 6.5% UGs had excellent knowledge about clinical signs of breast cancer (p < 0.01). Peau d’orange appearance of breast was recognised as a clinical sign of breast cancer by majority (92.7%) of the participants. Nipple pruritus with/without excoriation was least recognised (48.7%) risk factor. 15.7% PGs and 32.3% UGs were not aware of nipple retraction as a clinical sign (p = 0.03).

Screening for breast cancer

Table 7 summarises participants’ practice of screening methods. Overall, 84.9% participants were convinced that breast cancer screening decreases breast cancer mortality. 61.2% (66.1% PGs vs. 41.9% UGs; p = 0.04) consider CBE as most relevant screening investigation followed by mammography (25%) (22.3% PGs vs. 35.5% UGs; p = 0.04) and BSE (13.8%) (11.6% PGs vs. 22.6% UGs; p = 0.04).

30.2% participants (32.2% PGs vs. 22.6% UGs; p = 0.21) regularly offer breast cancer screening, while 44.1% participants (40.5% PGs vs. 58.1% UGs; p = 0.21) offer screening on demand. 38.9% gynaecologists consider 31–40 years as an ideal age to start CBE. Ideal age to start BSE was 21–30 years for 50.7% participants, 36.8% teach BSE (41.3% PGs vs. 19.4% UGs; p = 0.02) to their patients, and 55.3% educate patients about risk factors for breast cancer on a regular basis (56.2% PGs vs. 51.6% UGs; p = 0.01). Mammography was preferred as screening method by 22.3% PGs versus 35.5% UGs (p = 0.04). 78.3% participants had mammography-available practice area, but 58.5% did not consider screening mammography cost-effective (57.9% PGs vs. 61.3% UGs; p = 0.72) for their patients and 41.4% participants (39.7% PGs vs. 48.4% UGs; p = 0.38) considered screening mammography a time-consuming process. 47.4% referred patient to an oncologist on suspicion of breast cancer, 28.3% participants referred to general/breast surgeon, and 24.3% chose to biopsy by themselves.

Beliefs about treatment of breast cancer

Table 8 summarises participants’ beliefs about breast cancer treatment. 0.7% participants would refer the patient with family history of breast cancer to a specialist, while rest (99.3%) preferred to follow up such patients by themselves. Modified radical mastectomy was the preferred surgery for breast cancer by 23.1% gynaecologists. Breast conservative surgery (BCS) was considered as good as mastectomy by 50.4% PGs and 41.9% UGs (p = 0.39). 51.3% gynaecologists fear leaving diseased breast behind after BCS (49.6% PGs vs. 58.1% UGs; p = 0.39). 91.5% gynaecologists agreed that dedicated breast unit will be helpful in improving the outcome of breast cancer patients. 88.2% gynaecologists were interested to volunteer for breast cancer awareness programmes.

We also compared the knowledge of gynaecologists practicing in teaching versus non-teaching institutions, but we did not find any significant difference in their knowledge. 85.7% gynaecologists practicing in teaching institution and 77.8% of gynaecologists practicing in non-teaching hospital had excellent to very good knowledge of risk factors for breast cancer (p = 0.36). 20.4% gynaecologists practicing in teaching institution and 17.5% of gynaecologists practicing in non-teaching hospital had excellent knowledge of clinical signs of breast cancer (p = 0.42).

Discussion

This is one of few studies which evaluate the knowledge and practices of gynaecologists about screening, risk factors, clinical signs and treatment of breast cancer and benign breast diseases in India. Gynaecologists are usually the primary contact points for breast-related complaints in Indian women; hence, we chose to conduct this study in this group of doctors. Average population served by doctors in Uttar Pradesh is 19,561 [11] unlike the recommended doctor–population ratio 1:1000 by WHO [12]. Due to discrepant undergraduate-to-postgraduate programme ratio in India, all practicing physicians may not have acquired speciality degree in obstetrics and gynaecology. Hence, our survey included undergraduate doctors also, who had been practicing gynaecology.

Majority of the participants in our study were found to possess satisfactory knowledge of clinical signs (82.2%) of and risk factors (67%) for breast cancer. This score was better in postgraduate doctors. Our results correspond to the results from similar studies which show [female] doctors have a mean knowledge score of 74% as compared to nurses who have a score of 35% [10]. Another study in general physicians found them having a good knowledge of risk factors for and clinical signs of breast cancer [13]. A study showed low KAP (knowledge, attitude and practice) score of breast cancer amongst female practitioners [14]. An Indian study in nurses found a knowledge mean score of 49% for breast cancer risk factors [15].

84.9% doctors in our study were convinced that breast cancer screening decreases breast cancer-related mortality, and 61.2% considered CBE as most relevant screening investigation followed by mammography (25%) and BSE (13.8%). The results correspond with the results of another study which has estimated the better cost-effectiveness of CBE for breast cancer screening in India compared to mammography unlike in developed countries [16]. Studies have argued that BSE alone as a screening method has failed to downstage the late stage of cancer presentation [17, 18], but can be used as a medium for enhancing public awareness about breast cancer. Although majority of participants in our study believe BSE and CBE should start in earlier years, this was not evident in their clinical practices as only 30.2% voluntarily perform CBE and 36.8% teach their patients about BSE.

Results from a study show that gynaecologists (92.3%) are more likely to recommend screening mammography by the age of 40 in comparison with family physicians (64%) and internists (65.1%) [19]. Another study in gynaecologists show that they have stronger belief in the effectiveness of mammography in reducing breast cancer mortality and are more likely to recommend mammography, in younger (40–49 years old) and older (70 years) women [20]. 66–87% women >45 years undergo screening mammography in developed nations [21], while studies from developing nations show that screening mammography may not be cost-effective [16, 22]. A WHO survey reported that rural women and women with middle or low socio-economic status have lesser access to screening mammography in comparison with urban women [23]. 78.3% participants in our study have mammography available in their area, yet 58.5% do not consider screening mammography cost-effective and 41.4% participants consider it a time-consuming process.

More than half of our participants were unconvinced that BCS has equivalent prognosis as mastectomy unlike majority of clinical trials which prove otherwise [24, 25].

This study emphasises the need for implementation of various teaching or medical education programmes on breast examination, breast diseases and cancer and the training programmes for gynaecologists in the preliminary management of breast diseases. They can also collaborate with breast surgeons to promote BSE and CBE across various sections of society. Further research to assess the knowledge of primary health care workers about breast cancer screening and clinical signs should also be evaluated as they are the first contact point for 70% of Indian population residing in rural India.

The limitation of our survey is that it does not take into account the cultural beliefs of various doctors and their draining population. Sociocultural issues including social taboos, caste, gender inequality, religious dynamics, blind faith in traditional medical practices, superstitions are more prevalent in rural India and pose a major hurdle in equal distribution of health facilities across the country [26]. The diverse health care system in India comprises of trained doctors, AYUSH, midwives, traditional medical practitioners and faith healers who exploit the vulnerable population who believe in chants, pujas (religious worship) and sacred powders as a better alternative to modern medicine, and these practices differ in various places and sections across the Indian society.

Also this study is limited to the doctors practicing in Uttar Pradesh and may not be generalised to all Indian gynaecologists. The southern states of India have been reported to have higher health standards and better training in comparison with north-central states of India [26, 27]; hence, the results may vary in other states.

Conclusion

Though the knowledge regarding risk factors, clinical signs and treatment of breast cancer as well as benign breast diseases seems to be adequate amongst the gynaecologists, this is not evident in their clinical practice. This study brings to light the knowledge versus practices of most frequently contacted group of doctors for breast diseases and hence the need for educating them by structured and continuous teaching programmes. Thus, we can ensure that women with breast diseases are better screened, assessed, treated and appropriately referred for improved outcomes.

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136(5):E359–E386

Thakur NA, Humne AY, Godale LB (2015) Delay in presentation to the hospital and factors affecting it in breast cancer patients attending tertiary care center in Central India. Indian J Cancer 52(1):102–105

Cancer Screening Guidelines | Detecting Cancer Early. Cancer.org. 2017. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/find-cancer-early/cancer-screening-guidelines/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer.html [cited 12 Dec 2017]

Somdatta P, Baridalyne N (2008) Awareness of breast cancer in women of an urban resettlement colony. Indian J Cancer 45(4):149–153

Gupta A, Shridhar K, Dhillon PK (2015) A review of breast cancer awareness among women in India: cancer literate or awareness deficit? Eur J Cancer 51(14):2058–2066

Bekker H, Morrison L, Marteau TM (1999) Breast screening: GPs’ beliefs, attitudes and practices. Fam Pract 16(1):60–65

Coleman EA, Lord J, Heard J, Coon S, Cantrell M, Mohrmann C, O’Sullivan P (2003) The Delta project: increasing breast cancer screening among rural minority and older women by targeting rural healthcare providers. Oncol Nurs Forum 30(4):669–677

Lurie N, Margolis KL, McGovern PG, Mink PJ, Slater JS (1997) Why do patients of female physicians have higher rates of breast and cervical cancer screening? J Gen Intern Med 12(1):34–43

Subbarao RR, Raja RS (2004) Gynecologist and breast cancer. J Obstet Gynecol Ind 54(5):439–448

Ibrahim NA, Odusanya OO (2009) Knowledge of risk factors, beliefs and practices of female healthcare professionals towards breast cancer in a tertiary institution in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Cancer 4(9):76

Ganesan L, Veena RS (2018) A study on inter-state disparities in public health expenditure and its effectiveness on health status in India. Int J Res Granthaalayah 6(2):54–64

Deo MG (2013) Doctor population ratio for India—the reality. Indian J Med Res 137(4):632–635

Kumar S, Imam AM, Manzoor NF, Masood N (2009) Knowledge, attitude and preventive practices for breast cancer among health care professionals at Aga Khan Hospital Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc 59(7):474–478

Abda N, Najdi A, El Fakir S, Tachfouti N, Berraho M, Chami Khazraji Y, Abousselham L, Belakhel L, Bekkali R, Nejjari C (2017) Knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practice towards breast cancer among general practitioner health professionals in Morocco. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 18(4):963–968

Fotedar V, Seam RK, Gupta MK, Gupta M, Vats S, Verma S (2013) Knowledge of risk factors and early detection methods and practices towards breast cancer among nurses in Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 14(1):117–120

Okonkwo QL, Draisma G, der Kinderen A, Brown ML, de Koning HJ (2008) Breast cancer screening policies in developing countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis for India. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(18):1290–1300

Semiglazov VF, Moiseyenko VM, Bavli JL, MigmanovaNSh Seleznyov NK, Popova RT, Ivanova OA, Orlov AA, Chagunava OA, Barash NJ et al (1992) The role of breast self-examination in early breast cancer detection (results of the 5-years USSR/WHO randomized study in Leningrad). Eur J Epidemiol 8(4):498–502

Thomas DB, Gao DL, Ray RM, Wang WW, Allison CJ, Chen FL, Porter P, Hu YW, Zhao GL, Pan LD, Li W, Wu C, Coriaty Z, Evans I, Lin MG, Stalsberg H, Self SG (2002) Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: final results. J Natl Cancer Inst 94(19):1445–1457

Corbelli J, Borrero S, Bonnema R, McNamara M, Kraemer K, Rubio D, Karpov I, McNeil M (2014) Physician adherence to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force mammography guidelines. Womens Health Issues 24(3):e313-9

Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Tancredi DJ, Saito NH, Rainwater J, Kravitz RL (2012) Screening mammography beliefs and recommendations: a web-based survey of primary care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res 6(12):32

American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2015–2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. 2015. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2015-2016.pdf [cited 30 Jan 2018]

Barfar E, Rashidian A, Hosseini H, Nosratnejad S, Barooti E, Zendehdel K (2014) Cost-effectiveness of mammography screening for breast cancer in a low socioeconomic group of Iranian women. Arch Iran Med 17(4):241–245

Akinyemiju TF (2012) Socio-economic and health access determinants of breast and cervical cancer screening in low-income countries: analysis of the World Health Survey. PLoS ONE 7(11):e48834

Agarwal S, Pappas L, Neumayer L, Kokeny K, Agarwal J (2014) Effect of breast conservation therapy vs mastectomy on disease-specific survival for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg 149(3):267–274

Litière S, Werutsky G, Fentiman IS, Rutgers E, Christiaens MR, Van Limbergen E, Baaijens MH, Bogaerts J, Bartelink H (2012) Breast conserving therapy versus mastectomy for stage I-II breast cancer: 20 year follow-up of the EORTC 10801 phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 13(4):412–419

Goss PE, Strasser-Weippl K, Lee-Bychkovsky BL, Fan L, Li J, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Liedke PE, Pramesh CS, Badovinac-Crnjevic T, Sheikine Y, Chen Z, Qiao YL, Shao Z, Wu YL, Fan D, Chow LW, Wang J, Zhang Q, Yu S, Shen G, He J, Purushotham A, Sullivan R, Badwe R, Banavali SD, Nair R, Kumar L, Parikh P, Subramanian S, Chaturvedi P, Iyer S, Shastri SS, Digumarti R, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Adilbay D, Semiglazov V, Orlov S, Kaidarova D, Tsimafeyeu I, Tatishchev S, Danishevskiy KD, Hurlbert M, Vail C, St Louis J, Chan A (2014) Challenges to effective cancer control in China, India, and Russia. Lancet Oncol 15(5):489–538

Rao M, Rao KD, Kumar AK, Chatterjee M, Sundararaman T (2011) Human resources for health in India. Lancet 377:587–598

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Uma Singh (MD), Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, KGMU for her contribution towards the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, G.N., Agarwal, A., Jain, V. et al. Understanding and Practices of Gynaecologists Related to Breast Cancer Screening, Detection, Treatment and Common Breast Diseases: A Study from India. World J Surg 43, 183–191 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4740-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4740-5