Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the commonest cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths among women. However, information about breast cancer is still limited in most parts of the developing world among reproductive-aged women, i.e. aged between 18 and 60 years. This has consequences for timely diagnosis and intervention, resulting in high mortalities in most cases. Effective breast screening practices such as; screening by trained healthcare professionals, mammography, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging play a vital role in early detection and treatment of breast cancers. The aim of this study was to assess the awareness and practice of breast cancer screening examination among reproductive aged women in Ghana. A cross-sectional descriptive survey of 1672 reproductive-aged women (between 18–60 years) was conducted in the northern (Tamale) and southern (Accra) sectors of the country. According to the population and housing census 2020, women are 16.5 million (50.1%) of which approximately 10.5 million (63.6%) are in the aged bracket of 18 to 60 years. All participants consented, were sampled randomly from communities in Tamale and Accra, and never reported to any health facility for any breast-related complications. A structured questionnaire was used to obtain responses about; awareness of breast screening programmes, knowledge of breast screening methods, knowledge of self-breast examination, willingness to undergo clinical-breast examination, and practice of self-breast examination.

Results

Responses were presented as frequency tabulations, while associations between the responses and age, education, marital status, employment status and religion were assessed by Chi-squared analysis, significant at p < 0.05. The results showed that awareness and practice of breast cancer screening methods were higher among the younger women (aged 18–30 years), with tertiary level education, married, employed and were predominantly Christians. Significant associations were found between knowledge, practice and all the factors except religion. Finally, even though 84% ot the participants were aware of breast cancer and mammography as the commonest and most effective and appropriate examination method, practice of breast cancer screening examination among the women were less than 10%.

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite the high awareness level of breast cancer screening examination of approximately 84%, practice of any of the known screening methods were just about 10%. We therefore recommend educational and health policies targeted at behavioral change that will stimulate a positive attitude to breast cancer screening practices. Additionally, efforts should be made by government and other stakeholders in healthcare to design targeted policies and improve public education techniques to promote the practice of breast cancer screening among women in Ghana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

In 2020, there were 2.3 million women diagnosed with breast cancer and 685 000 deaths globally. As of the end of 2020, there were 7.8 million women who were diagnosed with breast cancer in the past 5 years, making it the world’s most prevalent cancer [1, 2]. Breast cancer occurs in every country of the world in women at any age after puberty but with increasing rates in later life. Breast cancer screening methods have been found to help in the early detection of lesions and the methods include self-breast examination, clinical-breast examination and radiological imaging of the breast using mammography [3]. Screening for confirmation can also involve the use of other form of imaging modalities including ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Breast cancer is associated with significant morbidity and mortality among women in middle- and low-income countries [4, 5] due to delays in seeking health care for breast related complaints. In developing countries, late presentation at health care facilities by breast cancer patients has frequently been reported [6]. Delay in seeking treatment is largely due to lack of information and misconceptions about the disease. When women report to health facilities late and at advanced stages of the disease, little or no benefit is derived from any form of therapy [7,8,9]. In contrast, breast cancer patients in developed countries report early, and a significant proportion of them are initially detected by physical examination and various non-clinical screening methods, including breast palpation by an experience person or self-examination, which maybe confirm by mammography, MRI and or laboratory test [10, 11].

The prevailing rate of breast cancer diagnoses requiring treatment in Ghana has increased significantly [8,9,10, 12]. According to published GLOBOCAN 2020 data, Fig. 1, 4 482 (31.8%) breast cancer cases are detected in Ghana of which less than 10% are successful treated. However, early detection has been found to be key to early diagnoses leading to better breast cancer care and a high possibility of successful treatment. In a study by Zahoor et al. [12] and Goncalves et al. [13] among Pakistani and Brazilian women respectively, shows that failure in breast cancer care is due to late presentation in health facilities hence late diagnoses leading to low success rate. Additionally, factors which lead to delay in diagnoses are lack of knowledge on regular breast screening for early detection and hence successful treatment. In addition, attitude towards breast screening, poor knowledge about breast cancer screening benefit and lack of knowledge on various methods of breast cancer screening [14] are some other factors.

The aim of this study was to assess the awareness of breast screening programmes, knowledge of breast screening methods, knowledge of self-breast examination, willingness to undergo clinical-breast examination, and practice of self-breast examination among reproductive-aged women in selected communities in Accra (the largest and referral health care facility in Southern Ghana) and Tamale, (the largest and referral health care facility in northern Ghana). This is to help identify reasons why breast cancer patients report to health facilities seeking medical cancer care late and in advance stage of the disease. It is also to provide bases for intervention by policy makers in Ghana.

2 Methods

2.1 Study location selection and setting

Ghana has sixteen geographical regions which together currently constitute a population of approximately thirty-two million people (comprises 50.7% females and 49.3% males) based on the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) population and housing census 2020 [15]. According to GSS, published Population and Housing census, 2020, of the 50.7% female population, 68% are within the reproductive age bracket of 18 to 60 years [15].

Data was collected from two selected sites as focal zones in Ghana (Fig. 2), With Accra and Tamale representing the southern and northern zones respectively. Tamale (blue circle) and Accra (yellow circle) were purposively selected to represent the northern and southern zones respectively. These two cities were selected for several reasons including; accessibility, mostly served as referral hospitals within the two zones. In addition to the highest literacy rates, highest social interactions, highest use of internet and social media, and the highest concentration of radio and television stations, therefore the capacity of women to be informed was expected to be the highest within the zones. Additionally, it is also due to the cosmopolitan nature of the two cities, which is representative of the country as a whole with several health facilities within the catchment area. Study participants were randomly sampled from the communities and the health facilities within these two zones. The facilities selected included; Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Greater Accra regional hospital, Cocoa clinic, University of Ghana Medical Centre and GAEC Hospital all in Accra. Those selected in Tamale include; Tamale Teaching Hospital, Tamale Central Hospital, SDA Hospital and UDS campus Clinic.

2.2 Study design

A cross-section of women within the reproductive age (i.e., 18 to 60 years ± 5 years) was sampled from selected communities within Tamale and Accra to respond to a structured questionnaire aimed to elicit from participants information about their awareness of breast screening programmes, knowledge of breast screening methods, knowledge of self-breast examination, willingness to undergo clinical-breast examination, and practice of self-breast examination.

The participants were selected women who had never had a referral for breast-related clinical conditions. The investigated issues included the awareness on breast cancer screening programmes in health facilities in Ghana, the awareness about breast examination methods, the knowledge of participants on self-breast examination, the willingness of participants to have their breasts examined by a qualified health professional, and whether participants practice breast examination of any form either on their own or with the support of others. In addition to the frequencies of responses to these questions, associations between these themes and five socioeconomic variables were investigated to determine if these variables influenced the responses of participants. These variables were age group, level of education, marital status, employment status, and religious belief.

2.3 Study participants

2.3.1 Sample size

A total of one thousand six hundred and seventy-two (1672) women out of the collected three thousand (3,000) women met the selection inclusion criteria participated in the study. The sample size was calculated using the modified Cochran’s statistical formula (Cochran, 1977) and Charan and Biswas [28].

where,

- n0:

-

the Crochran’s sample size

- e:

-

the margin of error = 5%

- p:

-

the estimated proportion of the population which has the attributes of the sample in question

- q:

-

1 – p

- z:

-

the confidence level

where p = 0.15, q = 0.85, z = 5 and e = 0.05

Hence a sample size of at least 1275 will be accepted by both Cochran statistical formula and Charan and Biswas [28] publication.

Based on this, a sample size of 1275, or better (1672) was agreed to represent the population.

2.4 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Apparently healthy women between the ages of 18 and 60 years ± 5 years were contacted for participation in the study. Those of them who had a history of breast cancer, and those who have ever had a referral to a health facility for medical attention or radiological investigation relating to breast illness or conditions were excluded from the study.

2.5 Sampling procedure

Each of the two geographical areas for the study was divided into sub-units (national categorization of electoral constituencies), which were subsequently divided into smaller units (cluster of geographically close suburbs). Within each suburb, the cluster random sampling technique was used to zone a number of houses from which women were selected using the simple random sampling technique [29]. In each zone the participants were selected based on the inclusive criteria and the study objectives. Those who showed willingness to participate in the study, ability to answer questions related to the five study objectives and provided explicit consent participated in the study.

2.6 Data collection

Those who were able to read and write, self-administered a structured questionnaire (in Appendix Tables 7 and 8), otherwise they were assisted by a one-on-one administration, which provided interpretation of the questions in the local language. The data collected were participants’ health habits and past illness related to their breasts were taken. Additionally, information on participants knowledge on breast cancer self-examination for general signs such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual was recorded. Furthermore, the key questions that were asked were focused on whether respondents were aware of breast screening examination, the various breast screening examination methods, whether they had knowledge about self-breast examination, whether participants think breast cancer screening was necessary, and whether they will consent to breasts examination by health professionals. Information on sociodemographic variables was also collected using the structured questionnaire. Data was collected between September 2021 and August 2022.

2.7 Data analysis and presentation

Data analysis was conducted using the Minitab software package (version 17; Minitab Inc., State College, Pennsylvania, USA). The data was analyzed by descriptive statistical methods, and the results were presented in frequency/percentage distribution tables. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using Chi-squared cross-tabulation. Associations were significant at a critical value of p < 0.05.

2.8 Ethical considerations

Approval was given for the research by the participating facilities and the ethical and Protocol Review Committee of the College of Basic and Applied Science, University of Ghana and the Participating Health Facilities. Additionally, the protocol and the application of same for this study was granted ethical clearance by the various Committees. The methods were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations as outline by the ethical and Protocol Review Committee of the College of Basic and Applied Science, University of Ghana and the Participating Health Facilities. All participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity throughout the study.

3 Results

The results are presented on six themes: characteristics of participants; awareness about breast cancer screening programmes; awareness about breast examination methods; knowledge on self-breast examination; willingness to undergo breast examination; and practice of breast examination.

3.1 Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of the study participants according to the subcategories of their sociodemographic characteristics.

3.2 Awareness about breast cancer screening programmes

The proportion of the participants who were aware or otherwise about breast cancer screening programmes in Ghana, and the demographic characteristics that may possibly influence their awareness are shown in Table 2. All associated variables had significant association (p < 0.001) with awareness except religion (p = 0.815).

Awareness about breast cancer screening programmes was common among the youngest age group (18–30 years), pre-tertiary education level females, married women, women in employment, and Christian women.

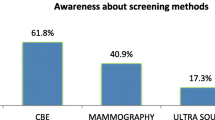

3.3 Awareness about breast examination methods

Table 3 shows the frequencies of women, who were aware of various breast examination methods stratified by demographic variables. Apart from religion (p = 0.216), all other variables had a significant (p < 0.05) influence on awareness about breast examination methods. Awareness about various breast examination methods was highest among females aged between 18 and 30 years, those who had pre-tertiary education, married women, employed women, and Christian women.

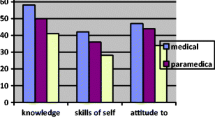

3.4 Knowledge about self-breast examination

Participants’ knowledge about self-breast examination and associated demographic factors are shown in Table 4. Among the demographic factors, only marital status did not have a significant association with their knowledge about self-breast examination (p = 0.113); age, education, religion and employment status each had a significant association (p < 0.05) with knowledge. A significant proportion of women aged 18–30 years, at pre-tertiary level, married, employed, and believing in Christianity had knowledge about self-breast examination.

3.5 Willingness to undergo breast examination

Table 5 shows the proportion of women willing to have their breasts examined by a qualified health practitioner, and demographic factors that can influence their willingness. Significant factors (p < 0.05) that may influence the decision of the women to have their breasts examined by a health practitioner were their level of education and their employment status. However, none of age, religion and marital status had influence on willingness to be examined (p > 0.05).

Meanwhile, women of ages 18–30 years, with tertiary level education, married, employed and of Christian persuasion were more willing to have their breasts examined by a health practitioner.

3.6 Practice of breast examination

The frequencies of women who practice self-breast examination and associated factors that influence their practice of the self-breast examination are shown in Table 6. All factors, except religion, had significant association with practice of self-breast examination. Breast self-examination was mostly practiced by women within the age bracket of 18–30 years, those who attained tertiary education level, married, employed and were of Christian persuasion.

4 Discussion

Although the age range regarded consistently as reproductive normally falls between 15 and 49 years [12], we chose to extend the age limit to be between 18 and 60 years, in order to observe how younger and women older than the upper limit will respond to the questionnaire. Indeed, we consistently observed a clear pattern of differences in the responses between the younger and the older women sampled for this study (as observed across the various Tables). The youngest age category reported the highest frequency of awareness about breast cancer screening programmes of 34%, while the oldest age group reported the least 10%. Additionally in terms of screening methods 33% of the younger participants were aware as against 9%. Furthermore, 32% had knowledge and associated factors about breast examination for younger participants as against 9% for the elderly participants. Finally, 18% for younger generation are willing to undertake breast screening as against 5% for the older generation. Hence the study can conclude that awareness of breast screening was most likely influenced by age as observed in recent studies reported in references [9, 11,12,13].

Furthermore, information about the availability of breast cancer screening programmes at various health facilities was obtained by the participants from various sources including; healthcare providers, family members and friends, print and electronic media, and social media.

Additionally, employed and married Christian women who had mostly had pre-tertiary education reported the highest frequency of awareness 48%. Awareness was observed to be significantly influenced by age, level of education, marital status, and employment status of the women of approximately 34%. This finding agrees with observation by previous studies where age, level of education, employment in the nursing profession, marriage status, and higher income levels have been reported to be associated with awareness about breast cancer [13,14,15,16].

The commonest breast examination methods known by most of the participants were physical, ultrasound and mammography examinations. Mammography examination was believed by most of the women to be the most effective and commonest examination procedure for breast cancer screening, similar to a report from a Nigerian study [17]. This significantly agreed with the scientific evidence that screening with mammograms is considered the international gold standard for detecting breast cancer early. Additionally, there is scientific evidence that no other breast cancer screening tool has a better combination of sensitivity and specificity in detecting breast cancer than mammography [18].

Similar, the study agrees with previous findings [13,14,15,16], that women in the youngest age category (18–30 years), employed, had up to pre-tertiary education, married and were Christians had the highest frequencies of awareness about the breast cancer examination methods as compared to older ages progressively. That is, in a decreasing order from 31–40, 41–50, and 51–60, that is 32%, 28%, 16%, and 9% respectively.

Apart from religion, all other factors had significant age base association with the awareness of breast cancer by the participants. That is religion had no significant effect on age related association with the awareness of breast cancer by the participants about 2% in average.

The results of the survey indicated that the age, level of education, religion and employment status each has an association with knowledge about how to perform self-breast examination. Marital status was not significantly associated with knowledge about self-breast examination. Consistently, the younger age category, those who had up to pre-tertiary level education, married and Christian women reported higher frequencies of knowledge about self-breast examination 34% than older participants of 9%. Our study considered strictly women who have never experienced any breast-related condition before; however, it has been observed that 24.3%, 7.6% and 3.8% of women sampled practiced self-breast examination, clinical-breast examination and mammographic examination, respectively. This study further reported and agreed with other study that women who had up to secondary and tertiary education were 2 and 4 times more likely to practice breast cancer screening [16]. Among women aged 40 years and older, mammography practice was reported to be about 3.1% [17] and 14.3% [18] as they were qualified for annual screening. This further supports our inclusion of women beyond the reproductive age in our survey (19). We, however, noticed that our participants in this age category had little 2% or no knowledge about breast cancer screening, which is rather disturbing.

Employment status and level of education of the women had significant association on their acceptability to have their breasts examined by a health practitioner (48%). Again, women who were Christians, married, had tertiary level education, employed and within the youngest age category (18–30 years) were more willing to undergo breast examination at a health facility (33%). The consistent lower frequency (9%) of awareness and practice of breast cancer screening among the Muslim women in this study (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 respectively) is attributable to the doctrine of the religion which does not exclusively permit them to have their breasts seen or even examined by health professionals. This confirmed the Islamic believed that no third party should see the body of a married/matured female. That is, exposing the intimate parts of the body is unlawful in Islam as the Quran instructs the covering of male and female sensitive body parts, and for adult females the breasts (Quran 24:31). Indeed, a report on breast screening practices among Arab women confirms that religion is a factor in their attitude to the concept about breast cancer screening [20]. Notably, majority of the women surveyed in this study believed that if they had no issues with their breasts, they did not have any reason to examine or have their breasts examined. Age group, level of education, employment and marriage statuses each had a significant role in the practice of breast examination among the women sampled. Highest frequencies of breast examination were reported by women within the 18–30-year-old age bracket, who had attained tertiary level education, were married, employed and Christians.

Even though the number of factors that influence awareness and practice of breast cancer screening is inexhaustive [20], those investigated in this study add to the body of literature on factors that are associated with the acceptance of breast screening programmes. To improve awareness and acceptance of breast cancer screening, efforts should be targeted at health motivation to increase compliance [18, 19, 21], systematic and comprehensive education should be provided by healthcare providers to particularly women of low or no formal education and low socioeconomic status [22,23,24], making information about breast cancer and screening methods accessible to all stakeholders [22, 25], and providing access to screening services to women of all ages [26, 27].

5 Conclusion

In summary, the study seeks to assess the level of awareness, and attitudes towards, breast cancer screening among reproductive-aged women in selected communities in Accra and Tamale, in Ghana. This is to help identify reasons why breast cancer patients report to health facilities seeking medical cancer care late and in advance stage of the disease. It is also to provide bases for intervention by policy makers in Ghana. In conclusion, despite the high awareness about breast cancer screening examination (84%), practice of any of the known screening methods were low among the women (10%). We therefore recommend educational and health policies targeted at behavioral change that will stimulate a positive attitude to breast cancer screening practices by Ministry of Health and the Gender and Children Affairs Ministry in Ghana. Hence, efforts should therefore be made by these two Ministries and other stakeholders including GHS and NGOs in healthcare to design targeted policies and improve public education techniques to promote the practice of breast cancer screening among women in Ghana.

6 Limitation

The level of education by the participants during the data collection did not allow the initial planned structural questionnaire with less personal interaction between the interviewers and the participants during the one-to-one interview with the participants. Additionally, the response of the participants tilted towards mammography and clinical examination than a level playing field with the breast self-examination practice or the physical examination which influences some of the response by the participants.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials for publication are all available upon request at any time.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). News room, an overview of global breast cancer cases. 2023.

Sung H, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. Can J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global health estimates 2020: Deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2019. 2020. Accessed 11 Dec 2020.

Kaniklidis C. Beyond the mammography debate: a moderate perspective. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(3):220–9.

Budh DP, Sapra A. Breast cancer screening. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. PMID: 32310510.

Adebamowo CA, Ajayi OO. Breast cancer in Nigeria. West African J Med. 2000;19(3):179–91.

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Can. 2010;127(12):2893–917.

Yeole BB, Kurkure AP. An epidemiological assessment of increasing incidence and trends in breast cancer in Mumbai and other sites in India, during the last two decades. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2003;4(1):51–6.

Aduayi OS, Aduayi VA, Adegbenro C. Breast cancer screening: an assessment of awareness, attitude and practice among female clients utilizing breast imaging services in south-western Nigeria. Science. 2016;4(3):219–23.

Pinsky RW, Helvie MA, Role of screening mammography in early detection, outcome of breast cancer. In: Ductal carcinoma in situ and microinvasive, borderline breast cancer. 13–26. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

Ullah Z, Khan MN, Din ZU, Afaq S. Breast cancer awareness and associated factors amongst women in Peshawar, Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. Breast Cancer. 2021;15:11782234211025346.

Zahoor S, Lali IU, Khan MA, Javed K, Mehmood W. Breast cancer detection and classification using traditional computer vision techniques: a comprehensive review. Curr Med Imaging. 2020;16(10):1187–200.

Goncalves R, Formigoni MC, Soares JM, Baracat EC, Filassi JR. Ethical concerns regarding breast cancer screening. In: Bioethics in medicine and society. Intech Open; 2020.

Fletcher SW, Elmore JG. Mammographic screening for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1672–80.

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). Population and Housing Census, October 10, 2022, Version 1.0. 2022. DDI-GHA-GSS-2021PHC-2021-v1.0.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease indicators; indicator definitions – reproductive health. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2015.

Madanat H, Merrill RM. Breast cancer risk-factor and screening awareness among women nurses and teachers in Amman, Jordan. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(4):276–82.

Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727–37.

Chong PN, Krishnan M, Hong CY, Swah TS. Knowledge and practice of breast cancer screening amongst public health nurses in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2002;43(10):509–16.

Donnelly TT, Al Khater AH, Al Kuwari MG, Al-Bader SB, Al-Meer N, Abdulmalik M, Singh R, Chaudhry S, Fung T. Do socioeconomic factors influence breast cancer screening practices among Arab women in Qatar? BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e005596.

Abeje S, Seme A, Tibelt A. Factors associated with breast cancer screening awareness and practices of women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1):1–8.

Akhigbe AO, Omuemu VO. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of breast cancer screening among female health workers in a Nigerian urban city. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):1–9.

Tahmasebi R, Noroozi A. Factors influencing breast cancer screening behavior among Iranian women. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2011;12(5):1239–44.

Donnelly TT, Al Khater AH, Al-Bader SB, Al Kuwari MG, Al-Meer N, Malik M, Singh R, Jong FC. Arab women’s breast cancer screening practices: a literature review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(8):4519–28.

Wu Z, Liu Y, Li X, Song B, Ni C, Lin F. Factors associated with breast cancer screening participation among women in mainland China: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e028705.

Ahmadian M, Samah AA. A literature review of factors influencing breast cancer screening in Asian countries. Life Sci J. 2012;9:585–94.

Edgar L, Glackin M, Hughes C, Ann Rogers KM. Factors influencing participation in breast cancer screening. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(17):1021–6.

Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(2):121–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7.

Omair A. Sample size estimation and sampling techniques for selecting a representative sample. J Health. 2014;2(4):142. https://doi.org/10.4103/1658-600X.142783.

Cochran WG. Sampling Techniques. 3rd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York. 1977.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Ghana Atomic Energy Commission and the ICTP through the Associate program (2020–2025) for the support I received from the two institutions. Additionally, I acknowledge the participating facilities including; Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Greater Accra regional hospital, Cocoa clinic, University of Ghana Medical Centre and GAEC Hospital all in Accra. Tamale Teaching Hospital, Tamale Central Hospital, SDA Hospital and UDS campus Clinic for allowing me to carry out the research in their facilities.

Funding

I personally funded this study with my own resources (no external funding was secured and used for this study).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the Authors were involved pre and post data collection and analysis during the study. The following specific activities were done by the Authors: Concept Note: IS., A-NM, YBM, TAS., FH, ENM and AkA. Pre-data collection activities including application for ethical clearance: IS, A-NM, YBM, TAS. Data collection and analysis: All Authors (IS, A-NM, YBM, TAS, FH, ENM and AkA). Drafting of Text: IS, ENM and AkA, FH, TAS. Review of Text: IS, A-NM, YBM, TAS, FH, ENM and AkA. Statistical analysis: IS, FH, AkA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Approval was given for the research by the participating facilities and the ethical and Protocol Review Committee of the College of Basic and Applied Science, University of Ghana and the Participating Health Facilities. Additionally, the protocol and the application of same for this study was granted ethical clearance by the various Committees. The methods were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations as outline by the ethical and Protocol Review Committee of the College of Basic and Applied Science, University of Ghana and the Participating Health Facilities. All participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity throughout the study.

Consent to participate

Each participant gave informed consent at study entry and offered the choice to exit from the study at any point during data collection without providing a reason for doing so.

Consent for publication

Each participant gave informed consent for the publication of the study entry and gave their approval for subsequent publication.

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 The structural questionnaire

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shirazu, I., Mumuni, AN., Mensah, Y.B. et al. Awareness and knowledge on breast cancer screening among reproductive aged women in some parts of Ghana. Health Technol. 14, 317–327 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-023-00812-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-023-00812-9