Abstract

Background

Total gastrectomy (TG) and proximal gastrectomy (PG) are used to treat upper-third early gastric cancer. To date, no consensus has been reached regarding which procedure should be selected. The aim of this study was to validate the usefulness of preserving the stomach in early upper-third gastric cancer.

Methods

Between 2004 and 2013, 201 patients underwent PG or TG at our institution for treatment of upper-third early gastric cancer. According to the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 192 cases were enrolled in this study. One-to-one propensity score matching was performed to compare the outcomes between the two groups.

Results

The operation time was shorter in the PG group. Although no significant difference was observed, the PG group had less bleeding and fewer postoperative complications. R0 resection rate was 100%, and no surgery-related deaths were observed. The frequencies of reflux symptoms and anastomotic stenosis were significantly higher in the PG group, but could be controlled by balloon dilation and drug therapy. The maintenance rates of body mass index and lean body mass were significantly higher in patients who underwent PG than TG. The total protein and serum albumin values were higher in the PG group than in the TG group and remained statistically superior.

Conclusion

PG group exhibited better perioperative performance. Furthermore, better nutritional results were obtained in the PG group. Although the late stenosis and reflux symptoms must be addressed, the PG is a preferable surgical procedure for the treatment of early proximal gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite a declining incidence in Western countries, gastric cancer remains the third most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths and the fifth most common type of malignancy worldwide [1, 2], and surgical resection is the mainstay of curative treatment. While its overall incidence appears to be decreasing, the frequency of cancers in the upper third of the stomach and the gastroesophageal junction has been increasing in both Western and Asian countries [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

Two surgical procedures, total gastrectomy (TG) and proximal gastrectomy (PG), are used to treat early-stage gastric cancer located in the upper stomach as the standard therapies [11,12,13]. To date, no consensus has been reached regarding which procedure should be selected, although several comparative analyses of TG and PG have been performed regarding postoperative disorders and nutritional benefits [14,15,16,17,18].

To date, no prospective randomized comparative study of the outcomes of PG and TG has been published. In clinical practice, performing a prospective randomized study to compare the outcomes between different surgical procedures is difficult. Propensity score matching (PSM) has been proposed as a method to overcome selection bias and increase the evidence level in observational non-randomized studies [19, 20]. Therefore, PSM analysis has been widely used to estimate the effects of exposure using observational data.

In our institute, TG has been routinely performed to treat early-stage proximal gastric cancer, and PG with esophagogastrostomy [21] has been performed only when more than half of the distal stomach can be preserved. In this study, we intended to compare the short- and long-term postoperative complications and nutritional outcomes between PG and TG and assess the advantages of both surgical procedures.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between 2004 and 2013, a total of 1563 gastric cancer patients were admitted to the Department of Surgery, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases. During this period, 201 patients who underwent PG or TG for clinical early-stage upper-third gastric cancer (cT1N0M0, Clinical Stage I) were identified in a retrospectively maintained database. TNM staging was based on the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma, 3rd English Edition [22]. The clinicopathological features of these patients were reviewed retrospectively using hospital records. Only PG patients who underwent esophagogastrostomy reconstruction (EG) were enrolled in this study, and only TG patients who underwent Roux-en-Y reconstruction were included in this study. The reasons for exclusion from PSM analysis were as follows: double tract reconstruction (n = 5), interposition reconstruction (n = 2), double tract reconstruction with another malignancy (n = 1), and a combined operation (n = 1). Finally, 43 PG and 149 TG patients were enrolled in this study. The clinical characteristics and short-term and long-term nutritional outcomes were compared between the PG and TG groups.

Surgical approach

All operations were performed with curative intent. All the cases were performed by open laparotomy with D1 + lymph node dissection, and preserved the celiac branch of vagal nerve. In the PG group, esophagogastrostomy anastomosis was performed using a circular stapler (diameter 25 mm) in an end-to-side EG at the anterior wall 2 cm from the lesser curvature and 3 cm from the top of the remnant stomach to function as the new fundus. After TG, esophagojejunostomy with a circular stapler (diameter 25 mm) was used routinely for Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Proximal and distal resection margins were evaluated intraoperatively to confirm freedom from disease in all patients.

Definitions and procedure of follow-up

We conducted follow-up examination in all cases for 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months after surgery, and then every half year. Blood tests and radiograph were taken at all outpatient visits. As a postoperative surveillance, we performed a computerized tomography once a year. In the PG group, gastroduodenal endoscopy (GDE) was performed once a year after surgery to eliminate residual gastric cancer. In the TG group, GDE for postoperative surveillance was not conducted. Additional GDE was performed to all patients who had gastrointestinal symptoms such as acid reflux and stasis. Reflux symptoms were evaluated using the Visick score at 6 months postoperatively under no medication, and reflux esophagitis was assessed using the Los Angeles (LA) classification [23, 24].

PSM analysis

PSM analysis was conducted using a logistic regression model and the following covariates: age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification (ASA-PS), body mass index (BMI), tumor size, histology, and preoperative laboratory data (total lymphocyte count (TLC), total protein (TP), and serum albumin (ALB)).

Postoperative complications and nutritional outcomes

The clinical features (age, sex, performance status, ASA-PS, height, weight, BMI, tumor size, histology), postoperative early complications (0–30 days), postoperative late complications (after 30 days), nutritional status, body weight, body mass index (BMI), lean body mass (LBM), and laboratory data such as the TLC, TP, ALB, hemoglobin, and prognostic nutritional index (PNI) of patients were analyzed based on information gathered from retrospectively collected gastric cancer databases in our hospital. Anthropometric-based prediction equations such as the Deurenberg equation were used to calculate the LBM of patients [25]. The anthropometric-based prediction equations are shown below: Body fat (%) = (1.2 × BMI) + (0.23 × Age)−(10.8 × Sex)−5.4 (Male = 1, Female = 0). All patients were followed for at least 36 months.

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed with JMP® PRO software (JMP version 13.1.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The demographic and clinicopathological characteristics are summarized using descriptive analysis, and all qualitative values are presented as means and standard deviations unless otherwise specified. Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test and Pearson’s χ 2 test were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. All values were two-tailed, and P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. We used a caliper width of 0.2 of the pooled standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score for PSM.

Results

Patient characteristics after PSM analysis

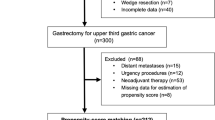

The study flowchart is summarized in Fig. 1. A total of 78 patients with upper-third early gastric cancer were included in the study; 39 patients were included in the PG group, and the remaining 39 patients were included in the TG group. The baseline characteristics of the PG and the TG groups are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the two groups with respect to all the preoperative background. Because we studied only upper-third early gastric cancer in this study, it was possible to operate PG similarly for patients who performed TG. The mean duration of postoperative follow-up period was 36 months or more, and no significant difference between two groups (P = 0.41).

Patient selection for evaluation of upper gastric cancer treatment. The study flowchart was summarized. PSM analysis was conducted by the following covariates: age, sex, ASA-PS, BMI, tumor size, histology, laboratory data (TLC, TP, ALB). We used 0.2 times of the pooled standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score as the caliper width for PSM. TG total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction, PG proximal gastrectomy with esophagogastrostomy reconstruction

Short-term outcomes

The surgical outcomes of patients undergoing PG and TG are detailed in Table 2. In the comparison of surgical characteristics, the median operation time was shorter in the PG group than in the TG group (P < 0.001). No significant difference in blood loss was observed between the two groups (P = 0.182).

Surgical complications classified as Clavien–Dindo grade II or higher are described in Table 2. The postoperative 30-day mortality rate was 0%. Concerning early postoperative complications, more cases (10 cases, 25.6%) were observed in the TG group than in the PG group (4 patients, 10.3%), but the difference was not statistically significant. One patient in the PG group (2.6%) and three patients in the TG group (7.7%) had Clavien–Dindo class III or higher complications. One patient in the PG group had angina pectoris. In the TG group, one case of anastomotic leakage, one case of dehiscence due to pancreatic fistula and an abdominal abscess secondary to pancreatic fistula were observed, and two cases of wound dehiscence and suture failure required reoperation. Curative resection (R0) was performed in all patients.

Long-term outcomes

The long-term outcomes are detailed in Table 3. The rate of patients with late complications was 7.7% in the TG group and 25.6% in the PG group. The incidence rates of reflux esophagitis and anastomotic stricture were greater in the PG group than in the TG group. Postoperative GDE was performed in all cases in the PG group and in 9 patients with digestive symptoms in the TG group.

The presence or absence of reflux symptoms according to the Visick score was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.234). However, reflux esophagitis classified as grade A or higher was observed in patients who underwent PG (9 cases, 23.8%) and TG (2 cases, 5.1%); this result was statistically significant (P = 0.019). Specifically, in 2 cases in the PG group and 1 case in the TG group, severe reflux esophagitis of LA classification C and D was observed, but no statistically significant difference was found (P = 0.556). Patients in the PG group (6 cases, 15.4%) suffered anastomotic stenosis more frequently than those in the TG group (1 case, 2.6%) (P = 0.038). The proportion of patients with anastomotic strictures requiring endoscopic balloon dilatation was significantly higher in the PG group than in the TG group (6/39, 18% vs. 1/39, 2.6%; P = 0.038). No cancer recurrence, including remnant gastric cancer, was observed in either the PG or TG groups.

Parameters of nutritional status

The body weight was significantly higher in the PG group than in the TG group at all observation points, as shown in Fig. 2a. The body weight in the TG group gradually decreased, but it gradually increased in the PG group after 6 months. The LBM was significantly lower in the TG group than in the PG group at all observation points (Fig. 2b). The rate of decrease in LBM was small compared to that in body weight. The rate of decrease was smaller in the PG group than in the TG group. No difference was observed between the two groups regarding the TLC after surgery (Fig. 3a). The changes in TP and serum ALB levels showed similar tendencies (Fig. 3b, c). A significant decrease in TP was observed in the TG group within 1 year after surgery, and no significant differences were observed at other observation points after 1 year (Fig. 3b). A significant decrease in the ALB level was observed in the TG group only at 3 months after surgery, and no significant differences were observed at other observation points. The PNI showed a similar trend to the ALB level (Fig. 3c). The serum hemoglobin level decreased in both groups immediately after surgery (Fig. 3d). Specifically, the value was lowest at 3 months after surgery; thereafter, it gradually recovered. The recovery rate was small in the TG group and roughly leveled off; however, the level in the PG group gradually increased, but 36 months after the operation, the recovery rate had not returned to the preoperative level. A significant difference was found only at 36 months after the operation in the PG group. Focus on PNI, a significant difference was observed only at 3 months after surgery, but no significant difference was noted after 6 months (Fig. 3e).

Postoperative outcomes of BMI (a) and LBM (b) after PSM. Postoperative outcomes of BMI (a) and lean body mass LBM (b) after PSM in groups of patients who underwent PG and TG. All postoperative data are reported as means ± SE relative to preoperative data. P < 0.05, significant. Y months after surgery

Discussion

The superiority of PG or TG during the perioperative period is controversial. Huh et al. [15] reported that patients who underwent PG suffered fewer complications after surgery than those who underwent TG. Other studies have reported that the TG procedure required an obviously longer operation time and caused greater intraoperative blood loss [17, 18, 26]. However, PG procedures involved a higher risk of late complications such as reflux symptoms and anastomotic stenosis. An et al. [14] reported rates of esophagogastric anastomosis-site stricture and reflux esophagitis of 38.2 and 29.2% after PG, respectively. Although we cannot perform a simple comparison because the PG group included various reconstruction methods, Masuzawa et al. [27] reported that both a bloated feeling (PG vs. TG 16.3 vs. 2.5%) and heartburn (PG vs. TG 18.4 vs. 11.5%) were more frequent in the PG group than in the TG group. Furthermore, others have concluded that reflux symptoms after PG were worse than after TG, and PG should be avoided for adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia, except for early-stage cancer [28]. In this study, the PG procedure had an obviously lower risk of Clavien–Dindo class III or higher surgical complications. The operation time was significantly shorter in the PG group than in the TG group. R0 resection could be performed, and the postoperative mortality rate was 0% in all patients. Of the 39 patients who underwent PG, 23.1% suffered from dysphagia due to gastroesophageal anastomotic stenosis, and 30.8% presented with epigastric soreness and reflux esophagitis diagnosed by endoscopy. These rates were similar to or slightly lower than those in previous reports. After TG, stenosis of esophagojejunostomy and reflux esophagitis occurred in only 5.1 and 15.4% of patients, respectively. Endoscopic balloon dilatation could effectively manage anastomotic stenosis in most patients, which is consistent with other reports [29, 30], and reflux symptoms were relieved by medication such as proton pump inhibitors.

In the postoperative nutritional evaluation, differences were found among the two treatment groups in terms of postoperative transitions. The laboratory data related to nutritional evaluation were generally good in the PG group. Specifically, body weight changes are a matter of grave concern after gastrectomy, and difficulty in maintaining body weight is a defining characteristic of post-gastrectomy syndrome. However, a change in body weight is an indicator of nutritional status in patients that can be easily evaluated [31]. Additionally, LBM is associated with immunity and quality of life, and a decrease of 5% or more after gastrectomy leads to increased drug toxicity such as that produced by adjuvant chemotherapy [32, 33]. Previous studies have reported that PG offers no advantage over TG in terms of weight preservation [14, 18]. However, Son et al. [34] reported that the PG group had a higher body weight than the TG group at the 2-, 3-, and 5-year postoperative follow-up evaluations, and the PG group showed an increasing tendency, whereas the TG group showed a decreasing tendency. In this PSM study, the PG group had a significantly lower weight loss rate than the TG group. Likewise, LBM was low in the PG group, and a decrease of 5% or more, which is said to be particularly high with regard to drug toxicity, was not observed in the PG group.

The present study has several limitations. First, the analysis was based on retrospective data collected at a single institution. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, a selection bias existed between the PG and TG groups. To reduce this bias as much as possible, statistical analysis was performed using PSM. Second, the study did not include assessments of patient symptoms or quality of life using validated questionnaires after surgery. Third, only the Visick score and LA classification were used for grading postoperative esophageal reflux. Therefore, a precise comparison may not have been performed between the two groups. Although some limitations were present, no RCT comparing PG and TG has been published, and by conducting the statistical analysis using PSM, the data could be rigorously examined and compared with past studies.

In conclusion, the PG group exhibited better perioperative performance than the TG group. Furthermore, better nutritional results were obtained in the PG group than in the TG group. Although late complications such as reflux and stenosis were observed in the PG group, they could be well managed by balloon dilation or drug administration. Therefore, this study provides important baseline data on the use of PG for minimally invasive treatment and functional maintenance of early-stage gastric cancer.

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R et al (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136:E359–E386

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL et al (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65:87–108

Dassen AE, Lemmens VE, van de Poll-Franse LV et al (2010) Trends in incidence, treatment and survival of gastric adenocarcinoma between 1990 and 2007: a population-based study in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer 46:1101–1110

Kusano C, Gotoda T, Khor CJ et al (2008) Changing trends in the proportion of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in a large tertiary referral center in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23:1662–1665

Steevens J, Botterweck AA, Dirx MJ et al (2010) Trends in incidence of oesophageal and stomach cancer subtypes in Europe. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22:669–678

Wu H, Rusiecki JA, Zhu K et al (2009) Stomach carcinoma incidence patterns in the United States by histologic type and anatomic site. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cospons Am Soc Prev Oncol 18:1945–1952

Yamashita H, Katai H, Morita S et al (2011) Optimal extent of lymph node dissection for Siewert type II esophagogastric junction carcinoma. Ann Surg 254:274–280

Crew KD, Neugut AI (2006) Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 12:354–362

Deans C, Yeo MS, Soe MY et al (2011) Cancer of the gastric cardia is rising in incidence in an Asian population and is associated with adverse outcome. World J Surg 35:617–624. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0935-0

Shang J, Pena AS (2005) Multidisciplinary approach to understand the pathogenesis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 11:4131–4139

Ooki A, Yamashita K, Kikuchi S et al (2008) Clinical significance of total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer. Anticancer Res 28:2875–2883

Katai H, Morita S, Saka M et al (2010) Long-term outcome after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for suspected early cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Br J Surg 97:558–562

Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Kubota T et al (2014) Long-term outcomes of patients who underwent limited proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer 17:141–145

An JY, Youn HG, Choi MG et al (2008) The difficult choice between total and proximal gastrectomy in proximal early gastric cancer. Am J Surg 196:587–591. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.09.040

Huh YJ, Lee HJ, Oh SY et al (2015) Clinical outcome of modified laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy compared to conventional proximal gastrectomy or total gastrectomy for upper-third early gastric cancer with special references to postoperative reflux esophagitis. J Gastric Cancer 15:191–200

Ikeguchi M, Kader A, Takaya S et al (2012) Prognosis of patients with gastric cancer who underwent proximal gastrectomy. Int Surg 97:275–279

Kondoh Y, Okamoto Y, Morita M et al (2007) Clinical outcome of proximal gastrectomy in patients with early gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 32:48–53

Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S et al (2002) Clinical outcome of proximal versus total gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer. World J Surg 26:1150–1154. doi:10.1007/s00268-002-6369-6

Austin PC (2011) An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res 46:399–424

Wang Y, Cai H, Li C et al (2013) Optimal caliper width for propensity score matching of three treatment groups: a Monte Carlo study. PLoS ONE 8:e81045

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2011) Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer 14:113–123

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2011) Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 14:101–112

Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL et al (1996) The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology 111:85–92

Visick AH (1948) Measured radical gastrectomy; review of 505 operations for peptic ulcer. Lancet 1:551–555

Deurenberg P, Weststrate JA, Seidell JC (1991) Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: age- and sex-specific prediction formulas. Br J Nutr 65:105–114

Wen L, Chen XZ, Wu B et al (2012) Total vs. proximal gastrectomy for proximal gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology 59:633–640

Masuzawa T, Takiguchi S, Hirao M et al (2014) Comparison of perioperative and long-term outcomes of total and proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: a multi-institutional retrospective study. World J Surg 38:1100–1106. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2370-5

Hsu CP, Chen CY, Hsieh YH et al (1997) Esophageal reflux after total or proximal gastrectomy in patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. Am J Gastroenterol 92:1347–1350

Akarsu C, Unsal MG, Dural AC et al (2015) Endoscopic balloon dilatation as an effective treatment for lower and upper benign gastrointestinal system anastomotic stenosis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 25:138–142

Lee HJ, Park W, Lee H et al (2014) Endoscopy-guided balloon dilation of benign anastomotic strictures after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gut Liver 8:394–399

Ryan AM, Healy LA, Power DG et al (2007) Short-term nutritional implications of total gastrectomy for malignancy, and the impact of parenteral nutritional support. Clin Nutr 26:718–727

Aoyama T, Kawabe T, Fujikawa H et al (2015) Loss of lean body mass as an independent risk factor for continuation of S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 22:2560–2566

Aoyama T, Sato T, Segami K et al (2016) Risk factors for the loss of lean body mass after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 23:1963–1970

Son MW, Kim YJ, Jeong GA et al (2014) Long-term outcomes of proximal gastrectomy versus total gastrectomy for upper-third gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer 14:246–251

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Drs. Yuki Ushimaru, Yoshiyuki Fujiwara, Yuji Shishido, Yoshitomo Yanagimoto, Jeong-Ho Moon, Keijiro Sugimura, Takeshi Omori, Hiroshi Miyata, and Masahiko Yano have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ushimaru, Y., Fujiwara, Y., Shishido, Y. et al. Clinical Outcomes of Gastric Cancer Patients Who Underwent Proximal or Total Gastrectomy: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. World J Surg 42, 1477–1484 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4306-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4306-y