Abstract

Background

Although various methods have been described for surgical treatment of pilonidal sinus disease, which is best is under debate. Tension-free techniques seem to be most ideal. We aimed to evaluate the effects of two tension-free methods in terms of patient satisfaction, postoperative complications, and early recurrence.

Methods

A group of 122 patients were prospectively included in the study. Patients were divided into two groups based on the operative method used: Limberg flap or Bascom cleft lift. Quality of life scores, pain scores, length of time for healing, hospital stay, surgical area-related complications, excised tissue weight, and early recurrence information were evaluated.

Results

Follow-up of patients in each group was completed. Patients in the Bascom cleft lift group had shorter operation duration, less excised tissue weight, better bodily pain score, and less role limitation due to physical problems score on postoperative day 10. There was no statistically significant difference between groups for the other criteria.

Conclusions

Although both techniques provided good results during the early period, the Bascom cleft lift procedure is a reliable technique that provides shorter operation duration and better quality of life during the early postoperative period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus is a common disabling disease that mainly affects active young adults. Whereas acute pilonidal abscess is generally treated with unroofing and drainage, management of chronic pilonidal sinus is still controversial [1]. Although numerous surgical treatment methods have been identified, there is no consensus for optimal treatment in the literature. There is not a high level of evidential data for ideal treatment selection. A recent Cochrane study suggested that “…off-midline closure should be the standard treatment,” is the most clear-cut [2].

Various methods have been defined for off-midline surgical treatment. Among them, the most commonly used is rhomboid excision with the Limberg flap. With this technique of flattening the natal cleft, a tension-free repair is made using a wide, well-vascularized flap. It comprises one of the best treatment methods, with a 0–16 % rate of surgical area-related complications and recurrence rate of 0–5 % [3]. The other off-midline technique is the cleft lift procedure described by Bascom. This technique was originally developed to deal with operations that had failed to heal or where symptoms continued to recur. Today, it is being carried out more and more as a first-time procedure. Although only a few studies have been conducted with this technique, such advantages as a short healing period and a low recurrence rate have been reported in cohort studies [4, 5].

The success of pilonidal sinus surgery is generally evaluated with one important factor being the long-term recurrence rate. Because it is characteristically common in a young and active age group, however, such features as patient comfort and satisfaction, ability to return to normal life, degree of social limitations, and level of mental ease stand out during the postoperative period. The have been no reported randomized studies that compare these two techniques. Therefore, we aimed to compare the two major surgical techniques used to treat pilonidal sinus disease in terms of early period patient satisfaction, wound healing duration, wound complication rate, and early recurrence.

Materials and methods

The plan was to conduct a prospective, controlled, randomized, single-center study. Following gaining approval of the local ethics committee, patients who presented to the Trabzon Numune Training and Research Hospital with the diagnosis of pilonidal sinus disease between November 2010 and October 2011 were included in the assessment. A total of 144 consecutive patients were assessed for eligibility, 122 of whom met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration principles. Following written informed consent, patients were divided into two groups based on the computer-assisted random number table. Patients in the first group underwent the Limberg flap technique, and the second group underwent the Bascom cleft lift technique (BCL). A nonsurgical team member recorded the patient data. The study protocol was submitted to the clinical trials registry managed by the National Institutes of Health (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01337869).

Patients

The main inclusion criterion was the presence of pilonidal sinus disease in a patient ≥18 years of age. We then assigned patients into groups in accordance with the modified Cruse-Foord classification (CF): patients with minor inflammation findings (CF class III) were included in the study after antibiotic treatment was commenced and 2 weeks had passed [6]. Patients presenting with acute abscess formation (CF class IV) or active psychiatric disease were excluded as were patients who refused to take part in the study.

A form was created before the surgery on which we recorded the patients’ information on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), CF class, previous treatments, and duration of symptoms. The primary endpoint of this study was the patient satisfaction assessment, which contained the postoperative pain score of the patient and quality of life (QoL) survey assessment. A visual analog scale (VAS) was utilized to assess the pain score. Patients were asked to mark the degree of pain they felt on the scale. The VAS scores varying between 0 and 100 were estimated with a ruler (on days 2, 10, and 30). A Short Form-36 (SF-36) survey was used for the QoL assessment (1-week form for day 10 and a 4-week form for day 30). The SF-36 is a short questionnaire with 36 items that measure eight multi-item variables: physical functioning (PF), role-physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role-emotional (RE), and mental health (MH) [7]. Patients were asked to fill out the survey at clinical visits. The responses were processed in the form found at http://www.qualitymetric.com/demos/sf-36.aspx/. The variable score of each variable ranged between 0 and 100. For all variables, higher results indicate better subjective health.

Postoperative complications, wound healing duration, duration of operation, hospital stay, and early recurrence were assessed as secondary endpoints. Fluid collections (seroma and hematoma), wound dehiscence (partial and total), and surgical-site infection (superficial and deep) were identified as postoperative surgical area-related complications.

Techniques

Before the operation, a single-dose of cefazolin 1 g was administered intravenously as a prophylactic antibiotic. All operations were performed under spinal anesthesia by the same team of two surgeons. Although a drain and the interrupted sutures are not routinely implemented for either technique, they were routinely utilized in this study for standardization (12F low-suction drain).

The excision and Limberg flap transposition (group A) were performed according to a technique described by Mentes et al. [8]. The area to be excised was mapped on the skin in a rhomboid form, and the flap was designed. The skin incision was deepened to the postsacral fascia. The flap was fully mobilized and transposed medially to fill the defect without tension. The wound was closed in two layers: the subcutaneous tissue with absorbable (2/0 polyglactin) sutures and the skin with nonabsorbable (3/0 polypropylene) interrupted mattress sutures (Fig. 2).

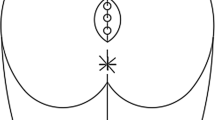

The Bascom cleft lift procedure (group B) was performed as described by Bascom and Bascom [4, 9]. The buttocks were pushed together, and the outer line of contact was marked. Beginning at 2 cm lateral of the midline, an incision was made 1–2 mm on the side of the sinus opening and curving around the anus. The skin from one side of the natal cleft was then elevated and excised. The skin on the opposite side of the cleft was undermined to a distance required to allow primary closure of the defect away from the midline without tension. The abscess cavity was curetted or scrubbed with gauze. The fat tissue of the natal cleft was approximated using absorbable (2/0 polyglactin) sutures. The wound was closed with 3-0 polypropylene interrupted mattress sutures (Fig. 3).

Definitions

“Operation time” was defined as the time between the initiation of the incision and the application of the last suture. The weight (grams) of excised tissue was determined using a precision scale and then recorded. During the postoperative period, patients were not advised about any limitations in movement. Patients were administered single-dose intramuscular diclofenac 8 h after the surgery and then were administered a diclofenac tablet every 12 h throughout the first day. Drains were removed when drainage decreased to <20 ml/day. Patients were discharged on the day of drain removal. Sutures were removed on postoperative day (POD) 10. The interval from the day of surgery to the day of discharge was recorded as the “hospital stay.” “Healing time” was described as the interval from the date of the operation until removal of the sutures. For patients with surgical area-related complications, the healing time was the interval until the wound was completely healed. The term “recurrence” was used when symptoms of the disease recurred some time after complete wound healing. The patients came for follow-up visits on PODs 2, 10, and 30 and then once every 6 months. At the end of the study, all patients were contacted again to obtain recurrence information.

Statistical analysis

There was no specific sample size calculation method for patient satisfaction scores because of their qualitative nature. Therefore, we used the sample sizes of the previously published articles for the primary outcomes, and 60 patients were determined for each group [10–14]. While the findings obtained from the study were assessed, SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) 16.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. If the data demonstrated normal distribution, the t test was used. If normal distribution was not demonstrated, the Mann-Whitney U-test and the Wilcoxon sign test were used. The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used for categoric data comparisons. The results were assessed with a 95 % confidence interval (CI) and a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 122 patients were included in the study, with 61 patients in each group. Follow-up of all patients was complete. The median follow-up period was 13 months. In the study, the average age was 25 years (range 18–48 years). The male/female ratio was 98/24. The distribution of demographic data of the patients included in the study according to groups is shown in Table 1. Both groups showed a homogeneous distribution in terms of age, sex, BMI, duration of complaints, CF class, and previous treatments.

The VAS scores on PODs 2, 10, and 30 and the SF-36 survey results on PODs 10 and 30 are shown in Table 2. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of VAS scores. However, the SF-36 survey showed statistically significant differences between the two groups on POD 10 in regard to bodily pain (BP) and role limitations due to physical problems (RP). The results of these variables were higher in the BCL patients (group B). A statistically significant difference was not observed between the other parameters.

Peroperative data and the results of the follow-up period are shown in Table 3. There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of operation duration and excised tissue weight, but there were no statistically significant differences for the other parameters. Infections were observed in 11 patients from both groups, with no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Superficial skin rashes and cellulitis were present in most of the patients. All infections were alleviated with antibiotic treatment alone. Wound dehiscence was mostly partial and was successfully treated with conservative treatment and dressings. All fluid collections healed after several aspirations, and no patient required reexploration.

Discussion

Karydakis stated that three factors are associated with pilonidal sinus development [15]. In contrast to his theory, Bascom maintained that pilonidal sinus is formed because of stretched follicles, and hair insertion is a secondary development [16, 17]. The common point shared by both theories is that the deep natal cleft creates a moist, hypoxic, anaerobic environment that bears a risk of developing surgical area complications. Hence, the vulnerability of the skin can be reduced by an off-midline closure. “Flattening the natal cleft” is the most significant point for the surgical technique of choice because it decreases both early postoperative period complications and recurrence rates [18–20].

Pilonidal sinus is a common disease during the second and third decades of life—a time of life when people are quite active (as employees or students). This point emphasizes the significance of postoperative satisfaction as patients are anxious to return home and continue their normal routines. In this study we assessed the satisfaction of participants through the postoperative pain score and QoL survey.

Although there are no reported studies that have compared the Limberg flap and BCL, some have reported that the Limberg flap causes less postoperative pain than excisions with primary closure or with secondary healing [10, 21, 22]. In our study, pain scores were evaluated on PODs 2, 10, and 20. A statistically significant difference was not observed between the two groups. We established lower VAS values in both groups compared with the values obtained from previous studies [10, 22–24]. We believe that such low pain scores were due to the tension-free nature of both techniques.

To assess QoL, we carried out an evaluation with the SF-36 survey on PODs 10 and 30. In the survey that evaluated the physical and mental conditions of patients, there was no significant difference between the two groups at the end of the first month. However, although there was no difference between mental functions in the assessment conducted on POD 10, significant results were observed between some physical functions in favor of the BCL group (RP, BP). We believe that the tension-free characteristic of these techniques—which has already been reported as a superior condition in terms of pain scores—creates positive effects regarding the movement of the patient. This outcome demonstrated that patients in the BCL group were able to carry out daily routines without severe physical limitation more effectively than the patients with the Limberg flap. In another study, the satisfaction rates of patients who had undergone a modified Limberg flap or the Karydakis procedure did not show any significant differences [1]. In contrast, with the BCL technique, unlike the Karydakis and Limberg operations, there is less tissue excision and sutures are not applied to the postsacral fascia, which could be responsible for the greater comfort during movement. Although there was no difference in the pain scores, better physical QoL can be explained with this theory. Furthermore, we did not apply any limitations on movement in this study, and patients continued their daily activities as much as possible. This is in contrast to other studies, which have recorded the amounts of time devoted to such movements as sitting on the toilet and walking without pain [10, 22, 25].

Another goal of pilonidal sinus surgery is to prevent recurrence. In our study, recurrence was observed in only one patient during the sixth month following complete wound healing. We observed fewer recurrences than have been reported in previous studies [3, 5, 8]. However, recurrence is a complication with a rate that increases over time rather than being observed during the early period after surgery [8]. Therefore, a short follow-up period is not sufficient for evaluation, and longer follow-up periods are essential [26].

Among the factors affecting QoL following pilonidal sinus surgery are surgical area-related complications. The anatomic location of the gluteal cleft, its proximity to the anal canal, and its occurrence in an area that is not visible to the patient increase the risk of infection. Infection rates were higher in our study than in previous studies [5, 8, 13, 23]. Infections observed in the form of cellulitis developed in the lower end corner of the incision in both of our groups. Factors such as contamination with stool during the postoperative period pose the risk of bacterial contamination. We believe that not paying attention to personal care instructions increases the risk of infection.

Although both techniques can be implemented without the use of a drain, we routinely utilized drains to standardize the study. We believe that despite there being less local fluid accumulation, a reason for the higher infection rates in the Limberg flap group (compared with previous studies) could be the use of drains [27, 28]. When the wound healing durations were compared, there was no significant difference between the two groups. Also, 90 % of the patients achieved complete healing by the end of 2 weeks.

Another difference between the two techniques was operation duration. Even though the importance of this short interval is limited, a statistically significant difference was seen between two groups. The Limberg technique necessitates a longer time for preparation because of the wider tissue required from under the postsacral fascia and its fixation to other side—which might be responsible for the difference in operation duration of the two techniques. Even so, the durations for both operative groups were shorter than operations in previous reports, probably because of the high volume of pilonidal sinus disease treated in our hospital [1, 5].

The study has some limitations. We did not evaluate the cosmetic results or time off work due to lack of an objective analysis parameter. The short follow-up period and difficulty calculating a sample size for primary outcomes are other limitations of the study.

Conclusions

Flattening the natal cleft during pilonidal sinus surgery, removing the deep intergluteal cleft, and tension-free restoration can decrease surgical area-related complications and patient discomfort during the early postoperative period. It can also lead to less chance of recurrence in the long term. The Limberg flap and BCL techniques meet these key goals. The BCL procedure is a reliable technique that presents better early-period QoL and a shorter operation. It provides results regarding early-period surgical area-related complications, healing period, and pain scores similar to those seen with the Limberg flap technique, which has been in use for a much longer time. Further clinical studies of a larger patient population with longer follow-up are needed to determine the better method for surgically treating pilonidal sinus disease.

References

Can MF, Sevinc MM, Hancerliogullari O et al (2010) Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing modified Limberg flap transposition and Karydakis flap reconstruction in patients with sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Am J Surg 200:318–327

McCallum IJ, King PM, Bruce J (2008) Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 336:868–871

Topgül K (2010) Surgical treatment of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus with rhomboid flap. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 24:7–12

Bascom J, Bascom T (2007) Utility of the cleft lift procedure in refractory pilonidal disease. Am J Surg 193:606–609

Abdelrazeq AS, Rahman M, Botterill ID et al (2008) Short-term and long-term outcomes of the cleft lift procedure in the management of nonacute pilonidal disorders. Dis Colon Rectum 51:1100–1106

Petersen S, Aumann G, Kramer A et al (2007) Short-term results of Karydakis flap for pilonidal sinus disease. Tech Coloproctol 11:235–240

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NMB et al (1992) Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 305:160–164

Mentes O, Bagci M, Bilgin T et al (2008) Limberg flap procedure for pilonidal sinus disease: results of 353 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg 393:185–189

Bascom J, Bascom T (2002) Failed pilonidal surgery: new paradigm and new operation leading to cures. Arch Surg 137:1146–1150

Ertan T, Koc M, Gocmen E et al (2005) Does technique alter quality of life after pilonidal sinus surgery? Am J Surg 190:388–392

Rao MM, Zawislak W, Kennedy R et al (2010) A prospective randomised study comparing two different modalities for chronic pilonidal sinus. Int J Colorectal Dis 25:395–400

Tezel E, Bostanci H, Anadol AZ et al (2009) Cleft lift procedure for sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum 52:135–139

Rushfeldt C, Bernstein A, Norderval S et al (2008) Introducing an asymmetric cleft lift technique as a uniform procedure for pilonidal sinus surgery. Scand J Surg 97:77–81

Dudink R, Veldkamp J, Nienhujis S et al (2011) Secondary healing versus midline closure and modified Bascom natal cleft lift for pilonidal sinus disease. Scand J Surg 100:110–113

Karydakis GE (1992) Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative process. Aust N Z J Surg 62:385–389

Kitchen PR (1996) Pilonidal sinus: experience with the Karydakis flap. Br J Surg 83:1452–1455

Bascom J (1980) Pilonidal disease: origin from follicles of hairs and results of follicle removal as treatment. Surgery 87:567–572

Nursal TZ, Ezer A, Calişkan K et al (2010) Prospective randomized controlled trial comparing V-Y advancement flap with primary suture methods in pilonidal disease. Am J Surg 199:170–177

Theodoropoulos GE, Vlahos K, Lazaris AC et al (2003) Modified Bascom’s asymmetric midgluteal cleft closure technique for recurrent pilonidal disease: early experience in a military hospital. Dis Colon Rectum 46:1286–1291

Nordon IM, Senapati A, Cripps NP (2009) A prospective randomized controlled trial of simple Bascom’s technique versus Bascom’s cleft closure for the treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Am J Surg 197:189–192

Jamal A, Shamim M, Hashmi F et al (2009) Open excision with secondary healing versus rhomboid excision with Limberg transposition flap in the management of sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. J Pak Med Assoc 59:157–160

Mahdy T (2008) Surgical treatment of the pilonidal disease: primary closure or flap reconstruction after excision. Dis Colon Rectum 51:1816–1822

Muzi MG, Milito G, Cadeddu F et al (2010) Randomized comparison of Limberg flap versus modified primary closure for the treatment of pilonidal disease. Am J Surg 200:9–14

Karakayali F, Karagulle E, Karabulut Z et al (2009) Unroofing and marsupialization vs. rhomboid excision and Limberg flap in pilonidal disease: a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum 52:496–502

Akin M, Gokbayir H, Kilic K et al (2008) Rhomboid excision and Limberg flap for managing pilonidal sinus: long-term results in 411 patients. Colorectal Dis 10:945–948

Doll D, Krueger CM, Schrank S et al (2007) Timeline of recurrence after primary and secondary pilonidal sinus surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 50:1928–1934

Topgul K, Ozdemir E, Kilic K et al (2003) Long-term results of Limberg flap procedure for treatment of pilonidal sinus: a report of 200 cases. Dis Colon Rectum 46:1545–1548

Petersen S, Koch R, Stelzner S et al (2002) Primary closure techniques in chronic pilonidal sinus: a survey of the results of different surgical approaches. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1458–1467

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guner, A., Boz, A., Ozkan, O.F. et al. Limberg Flap Versus Bascom Cleft Lift Techniques for Sacrococcygeal Pilonidal Sinus: Prospective, Randomized Trial. World J Surg 37, 2074–2080 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2111-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2111-9