Abstract

Background

Accurate pretreatment staging is essential to decision making for patients with esophageal and junctional cancers, particularly when choosing endoscopic therapy or a multimodal approach. As the efficacy of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has been reported as variable, we assessed it prospectively in a large cohort from a high-volume center.

Methods

The EUS data from 2007 to 2011 were reviewed and analyzed. We conducted a comparative analysis with computed tomography-positron emission tomography (CT-PET) staging and pathology. Survival was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier testing on EUS-predicted T- and N-stage cohorts.

Results

Altogether, 222 patients underwent EUS. Among patients undergoing primary surgical resection, preoperative EUS diagnosed the T stage correctly in 71 % (55/77) of cases. Sensitivity and specificity for T1, T2, and T3 tumors were 94 and 89 %, 55 and 80 %, and 66 and 93 %, respectively. Mean maximum standard uptake volume on CT-PET correlated moderately with the EUS T stage (r = 0.42, p < 0.0001). EUS accuracy for nodal disease was 65 %. Survival was statistically better for the EUS T1 group than for those with T3 tumors (p = 0.01). Nodal metastases diagnosed on EUS predicted a significantly worse prognosis than EUS-negative nodes on both univariate and multivariate analyses (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.005 respectively).

Conclusions

There was a significant relation between EUS T and N stages and overall survival. EUS demonstrated 71 % accuracy for the overall T stage. Staging accuracy of EUS for large lesions was less effective than for T1 tumors, underlining the need for a multimodal investigative approach to stage esophageal tumors accurately.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Precise staging of esophageal and junctional cancer is of great importance given the expanding treatment options available to patients today. For early-stage tumors, the advent of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) may spare patients with true mucosal disease from major surgery. For locally advanced disease, precise staging determines optimal treatment pathways, in particular as to whether patients should undergo multimodal approaches. Modern staging typically involves computed tomography (CT) imaging, often combined with 18F-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (CT-PET) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). EUS may have its greatest value in staging early disease, but the literature is confused and conflicting [1–6].

Endoscopic ultrasonography offers close-proximity imaging of the esophagus and its adjacent lymph nodes and organs. It is user-dependent, however, and expertise is needed to overcome the initial learning-curve inaccuracies [7–9]. The reported efficacy of EUS in staging esophageal cancer is variable, with conflicting reports pertaining to accuracy when staging early esophageal cancer [1, 2, 4]. A recent pooled analysis of 49 studies reported high pooled sensitivity for all EUS T stages [10], but it has not been borne out by single center reports. The literature on EUS for staging lymph nodes is also conflicting and confusing. One prospective study reported an accuracy of just 41 % [11], whereas others have reported accuracies of up to 87 % [1, 12].

Many studies are hampered by poor design—often retrospective and small study cohorts with heterogeneous patient groups. Technologic advances in EUS have outdated some earlier EUS reports. In our study from a high-volume center, the aim was to report the experience with EUS in a large prospective cohort performed by a single expert endoscopist. We evaluated its staging accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity in patients undergoing surgery alone, its predictive value in patients undergoing multimodal therapy, and its relative accuracy compared with that achieved by CT-PET.

Materials and methods

Study design

Data were compiled prospectively from August 2007 to May 2011. All patients had a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of esophageal or junctional cancer. The Esophageal and Gastric Center at St. James’s Hospital is a high-volume center, the largest in Ireland, with approximately 200 new referrals per year and a published audit [13, 14]. EUS and CT-PET results were recorded prospectively and subsequently compared to pathological staging and clinical endpoints. Patients were followed until the end of the study on June 30, 2011. The study had institutional review board approval. All patients after staging were discussed at multidisciplinary team meetings. Patients with predicted T1 disease confined to the mucosa would be selected for EMR (as part of a staging or therapeutic procedure), with or without RFA. Patients with T1, T2, and some early predicted T3 N0 patients were selected to undergo surgery alone. The third group included patients with predicted locally advanced tumors and node-positive tumors, who would undergo multimodal approaches as previously described [13, 14].

Staging

All patients underwent EUS and CT-PET. The results of these staging studies were reviewed by a nuclear medicine physician and a gastroenterologist in a nonblinded fashion as per standard clinical practice. For direct comparative purposes, clinical stage as determined with EUS was reviewed with the conclusive pathological stage only in patients undergoing primary surgery who were not subjected to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Initially, TNM reporting was based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union Internationale Contre le Cancer/tumor-nodes-metastases (AJCC/UICC/TNM), 6th edition (2002). This has been recently updated to AJCC 7th edition guidelines [15].

Endoscopic ultrasonography

The EUS examination was performed on all patients as per standard protocol and usually as a second endoscopy session following a confirmed diagnosis of esophageal or junctional carcinoma. A single experienced gastroenterologist (D. O’T) trained in diagnostic and interventional EUS performed all the procedures with the patient under conscious sedation (combination of fentanyl and midazolam). First, a forward-viewing endoscope was used to evaluate the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum to determine the proximal and distal extent of the tumor. This was followed by a radial EUS examination (Olympus) to evaluate the tumor for T stage, the presence of regional lymph node metastases, and the presence or absence of celiac axis nodes and hepatic metastasis. Endosonographic features predictive of lymph node metastasis—round shape, well-demarcated borders, hypoechogenicity—were used to determine whether visualized nodes were benign or malignant. The size of a lymph node (>10 mm) was considered to indicate a possible risk of malignancy, but it was not a definitive criterion [16]. If technically feasible and accepting the possibility that it could alter management, fine-needle aspiration was performed on suspicious nodes visualized on EUS that had been reported on PET and/or CT.

Statistical analysis

The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of EUS T and N staging focused on the surgery-only group as this cohort enabled direct comparison between EUS and the gold standard pathologic staging. These parameters were calculated using standard definitions.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 18.0) software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Using the overall study group to determine whether EUS T and N stages were a predictor of patient outcome, survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves. All patients were followed at regular intervals, and disease-specific death was recorded prospectively. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test. Differences between categoric variables were analyzed using the χ 2 test. Multivariate analysis was performed using Cox-regression analysis with a forward stepwise selection procedure to determine independent predictors of survival. Correlations between variables were investigated using the Spearman rho correlation coefficient: a value >0.50 indicated strong correlation and <0.30 poor correlation; values between these two extremes were viewed as indicating medium strength correlations. Statistical significance was defined by p ≤ 0.05.

Results

A total of 222 patients underwent staging EUS. Esophageal adenocarcinoma was the most common diagnosis, present in 74 % of patients (Table 1). Among them, 163 patients underwent surgical resection; 77 had surgery alone, and 86 had surgery following neoadjuvant therapy. The remaining patients underwent definitive chemotherapy ± radiotherapy (n = 32) or endoscopic (n = 5) or palliative (n = 22) therapy.

EUS and pathologic staging in patients undergoing surgery alone

The baseline characteristics in the surgery-only group (n = 77) are outlined in Table 2. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of EUS are outlined in Table 3. These results were then compared with reported accuracies by similar studies in the literature (Table 4).

Tumor location did not significantly alter the accuracy of EUS T staging (p = 0.541). EUS had the highest sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for T1 tumors, at 94, 89, and 91 %, respectively. In all, 24 T1 tumors were submucosal lesions, and EUS correctly diagnosed 20 (83 %). There were nine T1a tumors, and five (56 %) were correctly diagnosed as mucosal disease. EUS was less reliable for T2 tumors, with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 55, 80, and 77 %, respectively. T2 disease was more likely to be understaged as T1 (n = 4) than overdiagnosed as T3 (n = 1) lesions. EUS staging of T3 tumors had an accuracy of 76 %, with the inaccuracies tending to be understaged as T1 (n = 1) or T2 (n = 13, 41 %) tumors. There was one T4 tumor, which was understaged as a T3 lesion.

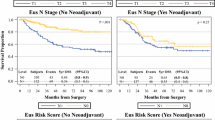

No nodal-stage (Nx) diagnosis was possible using EUS in two patients with bulky T3 lesions. Among the remaining 75 patients for whom an endoscopic nodal diagnosis was provided, 39 % (n = 29) had nodal metastases at the time of surgical resection. EUS was 30 % sensitive and 85 % specific for detection of nodal disease. Overall, 18 patients were diagnosed inaccurately as having no evidence of nodal involvement. Among these 18 patients, 72 % (n = 13) were confirmed at the pathology examination as having more invasive T3 and T4 tumors (Fig. 1).

a In the surgery-only group (n = 77) staging by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) predicted a lower proportion of N0 disease in the T1/T2 tumor group than in the T3/T4 tumor group (p = 0.032, χ 2 test). b A higher proportion of patients with T3/T4 tumors had nodal metastases (p < 0.0001, χ 2 test). Interestingly, there is a similar proportion of N+ patients in the T1/T2 tumor group during EUS and pathologic staging (p = 1.00), with a significant difference between the T3/T4 tumor groups (p = 0.0275)

Comparing EUS with CT-PET

All 222 patients underwent CT-PET. A positive (medium strength) correlation (r = 0.42, p < 0.0001) was seen between the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) and EUS-predicted T stage. Increasing uptake was seen with advancing T stage, being highest for EUS-predicted T4 tumors and lowest for T1 tumors (Fig. 2). The mean SUVmax for T1 tumors was 5.0 [95 % confidence interval (CI) 3.36–6.66], and for T2 tumors it was 12.48 (95 % CI 10.17–14.79). The mean SUVmax for T3 tumors was 12.73 (95 % CI 11.45–14.02), and for T4 tumors (n = 4) it was 18.1 (95 % CI 8.00–28.17). Kruskal-Wallis testing demonstrated a significant difference in mean SUVmax between T1 and T2, T1 and T3, and T1 and T4 tumors (p < 0.0001 for each). However; there was a wide range of variation for each T stage, so no specific cutoff could be determined for the different tumor groups. In the surgery-only group, of the patients who were diagnosed as having pathologically confirmed nodal metastases (n = 30), CT-PET results indicated that only 10 % (n = 3) were node-positive, and no evidence of nodal involvement was reported in 83 % (n = 25) or was unclear; Nx, in 7 % (n = 2).

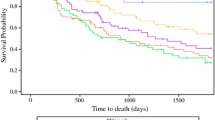

Association of EUS stage and disease-specific survival

Patients treated with palliative intent (n = 22) were excluded, and EUS T stage and patient survival were examined in 200 patients. Survival was greatest in the EUS T1 cohort [mean survival 3 years (95 % CI 2.5–3.4 years)] versus the T3 tumor group [mean survival 2.1 years (95 % CI 1.8–2.5 years] (p = 0.01). There was a significant survival advantage in the combined EUS T1/T2 cohort compared with the combined T3/T4 group (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). No significant differences were observed in survival (p = 0.592) between the T stage underdiagnosed and overdiagnosed patients when compared with the T stage accurately diagnosed patients.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve analyzed the difference in survival between EUS T1/T2 tumors (dotted line) and EUS T3/T4 tumors (solid line). A significantly longer survival was seen in patients diagnosed with T1/T2 tumors [mean 3.3 years, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 2.9–3.7 years] compared to an EUS diagnosis of T3/T4 tumors (mean survival 2.2 years, 95 % CI 1.9–2.6 years) (p < 0.0001)

Patients whose nodal metastases were diagnosed by EUS had a significantly worse prognosis than patients staged as having node-negative disease (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). Multivariate analysis showed that the pathologic nodal stage (p = 0.003) and the EUS nodal stage (p = 0.005) were significant predictors of survival.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve analyzed the difference between EUS N0 (dotted line) and EUS N+ (solid line) survival. A significantly longer survival was seen in patients diagnosed with node-negative disease (mean survival 3.3 years, 95 % CI 3.0–3.6 years) compared to an EUS diagnosis of N+ disease (mean survival 2.2 years, 95 % CI 1.9–2.5 years) (p < 0.0001)

Discussion

The literature reports considerable variation in the accuracy of EUS for staging esophageal and junctional cancer, contributing to concern surrounding the reliability of this investigative modality (Table 4). In the modern era, clinical staging has an effect on patients’ management decisions more than heretofore, in particular given the expanded portfolio of treatment options, particularly for early disease. These considerations prompted this study in our high-volume center where EUS and CT-PET have been part of our standard of care in recent years, but which we have not previously critically appraised.

Although EUS is not mandatory for staging early esophageal lesions, this study revealed that it has high sensitivity and specificity for pT1 tumors. EUS was accurate in diagnosing T1b submucosal tumors, with 83 % correctly staged. However, accuracy decreased for T1a tumors (n = 9), where five patients (56 %) were correctly diagnosed, although the numbers were small in these patient groups, and interpretation was difficult. It was for this reason that we decided it was better to group all T1 tumors together for analysis. It is important to emphasize that for staging T1a mucosal tumors EMR has shown greater sensitivity and specificity than EUS [17, 18]. Therefore, EMR has become standard practice at our center for staging early esophageal malignancies rather than EUS alone [19]. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy decreased for pT2 and pT3 tumors compared to pT1 lesions. Our results showed that EUS was moderately accurate for T staging and fell within the published range from other modern series, where ≥75 % indicates good predictive value [3, 5, 6].

EUS has less value for nodal staging, with a sensitivity of just 30 % in this series and an accuracy of 65 %. FDG-PET has demonstrated superiority to endoscopic staging for nodal metastases, with high specificity rates ranging from 89 to 98 % [20, 21]. When combined with CT, the accuracy further increases [22]. Hence, a combined staging approach is advocated at our center. Interestingly, however, staging was not improved by concurrent CT-PET in 90 % of patients with nodal disease in the surgery-only cohort—probably suggesting the existence of a small group of patients with micrometastases involving nodes at the time of surgical resection that clinical staging failed to detect. This may be related to some patients not fitting the standard criteria of nodal disease at the time of EUS. The study suggests that EUS N0 results should be interpreted with caution, particularly in patients with T3 and T4 tumors by EUS criteria.

We also demonstrated a medium strength correlation between CT-PET SUVmax and EUS T stage. However, wide variation in the SUVmax levels indicated that CT-PET was a less effective tool than EUS for staging esophageal cancer T stages—results consistent with those from other series [23, 24]. This signals that EUS is the more effective staging device for esophageal tumor T stage.

Zuccaro et al. [1] performed the largest study to date comparing the reliability of EUS staging to the gold standard pathologic staging in a surgery-only treatment group. However, their study commenced in 1987 and was completed in 2001, so it is probably out of date and did not factor in the technologic advances in endosonography seen over the past decade. Although these authors did not find any significant difference associated with changing the type of echo-endoscope over the study course, they acknowledged concern about using three types of probe throughout the study. Their statistical analysis had to be adapted to include this variable. The poor accuracy of EUS in their study may also be related to the initial learning curves associated with EUS [7, 8], although the level of the endoscopists’ experience was not reported. The greatest accuracy was in the staging of T3 and T4 tumors, which represented 52 % of the study patients [1]. However, today neoadjuvant treatment is accepted internationally as the standard therapy option for T3 and/or N+ disease. Therefore, the true reliability of EUS for staging more advanced lesions in this modern treatment era will be difficult to calculate accurately. Our results, like others [10], confirm that EUS is accurate for early tumors and therefore plays an important role in therapy triage.

The majority of patients in our institution with predicted locally advanced and node-positive disease were treated with combined preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy. This contributes to the low sensitivity for diagnosing nodal metastases in a study such as this. Surgery-only groups are select cohorts in most modern esophageal centers, and multimodal groups cannot be evaluated as their response to therapy prevents direct comparison between endoscopic and pathologic staging. Survival analysis was seen as a potential way to determine the accuracy of EUS staging in the total cohort of 200 patients. Improved survival was shown in EUS-staged T1/T2 and N0 tumors. EUS N1 and pN1 disease were two independent prognostic variables. A reason for this may be that response to therapy in the multimodal treatment group separated these two variables and resulted in the EUS nodal stage not being influenced by the pathologic stage. Interestingly, this suggests that regardless of response to neoadjuvant therapy a clinical diagnosis of nodal spread is still associated with a poor prognosis.

Conclusions

The study shows that EUS has high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing T1 tumors overall, although there is reduced ability to differentiate between mucosal and submucosal tumors. Accuracies for T2 and T3 tumors were 77 and 76 %, respectively. Initial EUS prediction of nodal disease and T1 or T2 disease has significant prognostic value. The accuracy of EUS for detecting nodal disease is higher for early-tumor groups, but node-negative prediction for advancing T3 and T4 lesions should be made with caution. At present, the poor sensitivity and specificity of EUS when staging more-advanced lesions and differentiating between mucosal and submucosal T1 tumors highlights the continued need for a multimodal diagnostic approach, indicating that, by itself, EUS is less effective than some studies suggest.

References

Zuccaro G Jr., Rice TW, Vargo JJ et al (2005) Endoscopic ultrasound errors in esophageal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 100:601–606

Shimpi RA, George J, Jowell P et al (2007) Staging of esophageal cancer by EUS: staging accuracy revisited. Gastrointest Endosc 66:475–482

Shimoyama S, Yasuda H, Hashimoto M et al (2004) Accuracy of linear-array EUS for preoperative staging of gastric cardia cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 60:50–55

DeWitt J, Kesler K, Brooks JA et al (2005) Endoscopic ultrasound for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer: impact of increased use of primary neoadjuvant therapy on preoperative locoregional staging accuracy. Dis Esophagus 18:21–27

Kutup A, Link BC, Schurr PG et al (2007) Quality control of endoscopic ultrasound in preoperative staging of esophageal cancer. Endoscopy 39:715–719

Pech O, Gunter E, Dusemund F et al (2010) Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound in preoperative staging of esophageal cancer: results from a referral center for early esophageal cancer. Endoscopy 42:456–461

Lightdale CJ, Kulkarni KG (2005) Role of endoscopic ultrasonography in the staging and follow-up of esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:4483–4489

Lightdale CJ (1992) Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis, staging and follow-up of esophageal and gastric cancer. Endoscopy 24(Suppl 1):297–303

Rice TW, Boyce GA, Sivak MV (1991) Esophageal ultrasound and the preoperative staging of carcinoma of the esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 101:536–543 discussion 543–534

Puli SR, Reddy JB, Bechtold ML et al (2008) Staging accuracy of esophageal cancer by endoscopic ultrasound: a meta-analysis and systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 14:1479–1490

Lerut T, Flamen P, Ectors N et al (2000) Histopathologic validation of lymph node staging with FDG-PET scan in cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction: a prospective study based on primary surgery with extensive lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg 232:743–752

Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Wiersema MJ, Clain JE et al (2003) Impact of lymph node staging on therapy of esophageal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 125:1626–1635

Reynolds JV, Muldoon C, Hollywood D et al (2007) Long-term outcomes following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer. Ann Surg 245:707–716

Reynolds JV, Ravi N, Muldoon C et al (2010) Differential pathologic variables and outcomes across the spectrum of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. World J Surg 34:2821–2829. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0783-y

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC et al (eds) (2010) AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th edn. Springer, New York

Catalano MF, Sivak MV Jr., Rice T et al (1994) Endosonographic features predictive of lymph node metastasis. Gastrointest Endosc 40:442–446

Maish MS, DeMeester SR (2004) Endoscopic mucosal resection as a staging technique to determine the depth of invasion of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 78:1777–1782

May A, Gunter E, Roth F et al (2004) Accuracy of staging in early oesophageal cancer using high resolution endoscopy and high resolution endosonography: a comparative, prospective, and blinded trial. Gut 53:634–640

O’Farrell NJ, Reynolds JV, Ravi N et al (2012) Evolving changes in the management of early oesophageal adenocarcinoma in a tertiary centre. Ir J Med Sci (in press)

Flamen P, Lerut A, Van Cutsem E et al (2000) Utility of positron emission tomography for the staging of patients with potentially operable esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 18:3202–3210

Choi JY, Lee KH, Shim YM et al (2000) Improved detection of individual nodal involvement in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus by FDG PET. J Nucl Med 41:808–815

Roedl JB, Blake MA, Holalkere NS et al (2009) Lymph node staging in esophageal adenocarcinoma with PET-CT based on a visual analysis and based on metabolic parameters. Abdom Imaging 34:610–617

Van Westreenen HL, Westerterp M, Sloof GW et al (2007) Limited additional value of positron emission tomography in staging oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg 94:1515–1520

Gillies RS, Middleton MR, Han C et al (2012) Role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography in predicting survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery for oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 99:239–245

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by an Irish Cancer Society Research Scholarship award (CRS11OFA). The authors thank Ms. Zeita Claxton (Department of Surgery, St. James’s Hospital, Dublin) for prospectively following patient survival throughout this study.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Farrell, N.J., Malik, V., Donohoe, C.L. et al. Appraisal of Staging Endoscopic Ultrasonography in a Modern High-Volume Esophageal Program. World J Surg 37, 1666–1672 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2004-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2004-y