Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair has emerged as a viable alternative to the open procedure. To date, few studies have included validated measures of quality of life as end points. We compared quality-of-life outcomes following laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernia.

Methods

All laparoscopic repairs were performed via the totally extraperitoneal route (TEP). All open procedures were Lichtenstein repairs (LR). Hernia repairs performed between January 1999 and December 2006 were included in the study. Data was recorded prospectively and each TEP repair was matched with a LR for analysis. The SF-36 form was used to assess quality of life. Statistical significance was determined using the two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test.

Results

Three hundred fourteen procedures were performed during the study period, 164 (52%) had a TEP repair and 150 (48%) had a LR. Ninety TEP repairs were matched with 90 LR. Recurrence rates were 3% following TEP repair and 2% following LR. There was a significant difference between the laparoscopic and open groups in terms of physical function (p = 0.0001), physical role (p < 0.0001), bodily pain (p = 0.0029), general health (p = 0.0025), and emotional role (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of vitality (p = 0.2501), mental health (p = 0.08), or social functioning (p = 0.1677).

Conclusions

These data suggest that the TEP repair results in less postoperative pain, a quicker return to normal functional status, and improved quality-of-life outcomes with equivalent recurrence rates when compared to the LR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia surgery continues to evolve with laparoscopic repair now an alternative to open surgery [1]. A tension-free repair, whether achieved via laparoscopic or Lichtenstein repair (LR), is the procedure of choice [1–3]. The equivalence of laparoscopic repair has been demonstrated in a number of studies [2–5]. Many of these authors have shown that similar recurrence rates can be achieved laparoscopically and some have demonstrated less postoperative pain [6]. Few studies have addressed quality-of-life issues. In 2003, the Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews published an update to its original 2000 report comparing laparoscopic and open techniques for hernia repair; the updated report indicated that whereas laparoscopic repairs (i.e., transabdominal preperitoneal [TAPP] repairs and totally extraperitoneal [TEP] repairs) generally took longer and had a slightly higher rate of more serious complications than open repairs (0.005 vs. 0% and 0.001 vs. 0%, respectively), they also were associated with shorter recovery times [2]. The risk of serious complications has been allayed in more recent randomized controlled trials [1]. The overall risk of recurrence following laparoscopic repair in the earlier studies may also have been related to the surgeon’s level of experience [7]. The TAPP approach is easier to learn and perform than the TEP approach, and even experienced laparoscopic hernia surgeons report more technical difficulties with the latter [2]. Nonetheless, there is a growing body of literature suggesting that TEP repair, by avoiding entry into the peritoneal cavity, has significant advantages over TAPP repair [3], in particular, a reduction in the risk of trocar site hernias, small bowel injury and obstruction, and intraperitoneal adhesions to the mesh. In addition, TEP repair is also a cost-effective treatment option for patients with unilateral (primary or recurrent) hernia [2].

Possible benefits in terms of quality-of-life outcomes following TEP repair have not yet been fully determined, so it was with this in mind that this study was undertaken.

Patients and methods

TEP and Lichtenstein repairs of unilateral primary inguinal hernias performed between January 1999 and December 2006 were included in the study. Prior to January 2003 all inguinal hernias were repaired using the Lichtenstein technique. Subsequently, all repairs were attempted laparoscopically via the TEP approach. A flowchart on patient selection is shown in Fig. 1. All procedures, patient demographics, and follow-up data were recorded prospectively. This study involved a retrospective review of that database. Due to incomplete data because of either lack of complete follow-up or SF-36 forms, a case-matched study was performed. Each TEP repair was matched for age and gender with a LR. To reduce the bias associated with the learning curve, the first 50 TEP repairs were excluded from the analysis. Exclusion criteria also included bilateral and recurrent hernias. Patients with clinical evidence of a unilateral hernia and intraoperative evidence of a contralateral occult hernia were also excluded. All open hernias were repaired using the Lichtenstein technique. Both procedures were performed under general anesthesia.

The TEP repair involved a transverse incision at the level of the umbilicus on the side of the hernia, placement of a 10-mm trocar, and creation of the extraperitoneal space. Two 5-mm trocars were subsequently placed under direct vision. A 10 × 15 knitted prolene mesh was used. Tacks were used to fix the mesh only when a direct hernia was encountered. Tacks (Protack) were placed around the defect in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. No tacks were placed into periosteum. Bupivacaine 0.5% was used for both open and laparoscopic repairs titrated to body weight. For open repairs the local anesthetic was infiltrated around both the wound and the ilio-inguinal nerve. For TEP repairs infiltration around the port sites and into the preperitoneal space was employed. In both repairs skin closure was achieved using subcutaneous monocryl. The periumbilical fascial defect was closed with vicryl. The 5-mm working ports were not closed at fascial level. All patients were reviewed 1 month post surgery and every 6 month subsequently by clinical examination. Follow-up was discontinued at 5 years. Chronic pain was defined as pain present for more than 3 months following surgery. Its presence was recorded and the magnitude of the pain was accounted for by the SF-36 scores of individual patients. Dysesthesia was defined as the presence of a transient abnormal sensation of less than 6 months duration.

The Short-Form 36 was used to assess quality of life. This questionnaire was given to each patient on one occasion, at the first outpatient follow-up. The taxonomy of the SF-36 has three levels: (1) items, (2) eight scales that aggregate 2-10 items each, and (3) two summary measures that aggregate scales. Quality of life is assessed in terms of 8 facets: physical functioning (10 items), social functioning (2 items), role limitations due to physical problems (4 items), role limitations due to emotional problems (3 items), mental health (5 items), energy/vitality (4 items), bodily pain (2 items), and general health perception (5 items). Results were grouped and statistical significance was determined using the two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test. Quality-of-life outcomes were the primary end points of the study. The presence of chronic postoperative pain, return to functional activity, recurrence rates, conversion rates, technical failure rates, and postoperative complications were secondary end points.

Results

Three hundred fourteen procedures were included in the study, 164 (52%) had a TEP repair and 150 (48%) had a LR. Ninety TEP repairs were matched with 90 LR. Median follow-up was 32 months (range = 10-54 months). Patient demographics in terms of age and gender were similar (Table 1). There was no significant difference in recurrence, wound infection, or postoperative collection rates between the two groups. One TEP repair patient had an immediate postoperative recurrence for a resultant technical failure rate of 1.1%. The conversion rate from TEP to LR was 2%. There was a significant reduction in postoperative dysesthesia in the TEP group and a nonsignificant reduction in chronic pain (Table 1). In the TEP group 28 hernias were direct and had tacks used. The remaining 62 patients in the TEP group did not have tacks applied. In this group nine patients reported dysesthesia and four of these had a direct hernia. Three patients had chronic pain and two of these had a direct hernia. Conversions were all for technical reasons.

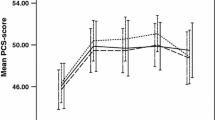

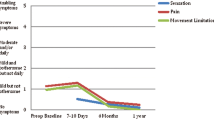

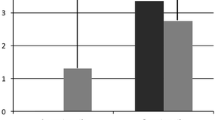

There was a significant difference between the laparoscopic and open groups in terms of physical function (p = 0.0001), physical role (p < 0.0001), bodily pain (p = 0.0029), general health (p = 0.0025), and emotional role (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of vitality (p = 0.2501), mental health (p = 0.08), or social functioning (p = 0.1677) (Figs. 2 and 3).

When overall results for the study were calculated, TEP repair resulted in a significantly better quality-of-life outcome for both mental (p < 0.0001) and physical (p < 0.0001) health compared to LR (Table 2). Previous studies analyzing laparoscopic versus Lichtenstein hernia repair in terms of quality of life are outlined in Table 3.

Discussion

Tension-free mesh repair of a primary inguinal hernia is the procedure of choice. This can be achieved laparoscopically [8]. Initial studies comparing laparoscopic versus conventional open repairs were limited by a certain number of factors, including failure of surgeons to overcome their learning curves [9–11]. Most of these studies compared the TAPP repair with a variety of open repairs. A Cochrane Review noted that TAPP and TEP repairs had similar outcomes and also noted that the incidence of serious complications was reduced from 5 in 1,000 with TAPP repair to 1 in 1,000 with TEP repair. TEP repair was therefore recommended as the laparoscopic procedure of choice [2]. Several studies have compared TEP and LR [12, 13]. Much of the literature concerning laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair has focused on recurrence rates and recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated equivalence with the Lichtenstein repair [1]. Our study focused on pain, return to functional status, and overall quality of life.

Several studies have investigated whether the laparoscopic technique or the open technique is superior. Neumayer et al. [14] concluded that the open technique is superior to the laparoscopic technique for mesh repair of primary hernias. However, there were limitations to that study. The average age of the study population was high and the health-related quality of life was below that of the general population. Subset analysis also revealed a particularly high rate of recurrence in two of the centers. That study also compared both TAPP and TEP with LR. Equivalence of TEP versus Lichtenstein repair in terms of recurrence rates has been demonstrated in a number of studies in both the short and long term [4, 15]. In our study, equivalent results in terms of recurrence were also demonstrated with acceptable conversion rates.

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence in the United Kingdom published revised guidelines in 2004. It concluded that laparoscopic surgery was associated with a significantly shorter time to return to usual activities in all of the studies that measured this outcome. Meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of TAPP repair revealed a return to normal activities approximately 3 days earlier than after open repair [16]. Overall, there were fewer cases of persistent pain 1 year after laparoscopic repair compared with open repair in both TAPP and TEP studies [2]. The Cochrane Review also demonstrated a quicker return to usual activities following laparoscopic repair and also documented less pain and numbness than with open surgery [2]. Our data mirrors these findings in terms of postoperative pain and return to physical functioning. In addition, postoperative dysesthesia was less in the TEP group.

Tacks to fix the mesh and prevent early recurrence are considered essential by some surgeons; however, they have been implicated as a possible contributing factor in groin pain following TEP repair. Their role in TEP repair has been investigated in a RCT [16]. Taylor et al. [17] concluded that mesh fixation did not reduce early recurrence and was associated with a significantly increased incidence of chronic pain. In addition, fixation contributes significantly to operative costs. We elected to use tacks only in direct hernias. While our study was not designed to investigate the contribution of tacks to post-TEP dysesthesia and pain, their contribution in our experience is minimal, perhaps because we do not place them into periosteum.

Much of the analysis of laparoscopic versus open hernia repair has focused on outcome in terms of recurrence and pain. Some studies have included quality-of-life outcomes as study end points. A review of the literature with respect to outcomes following laparoscopic versus open hernia repair revealed improvements in time to return to work and other activities and in quality-of-life outcome [18]. McCormack et al. [19] reviewed the literature in 2005 and concluded that both TAPP and TEP provided better outcomes in terms of quality adjusted life years than open repair. Most trials addressing quality of life after laparoscopic versus open hernia have evaluated the TAPP approach. Van Hanswijck et al. [20] identified eight trials that assessed quality of life following hernia repair in 7,032 patients and concluded that SF-36 scores were significantly higher in postsurgery laparoscopic hernia repair groups than in open hernia repair groups. Only one of these eight studies assessed the TEP approach. Conversely, another recent study of 216 patients found no difference between TAPP and LR [21]. In our study we found a significant improvement in all quality-of-life outcome measures following TEP repair except social functioning and mental health. Overall differences in physical and mental quality-of-life measures were significantly improved in the TEP group.

This study has some limitations. First, there was no preoperative assessment of quality of life. This requires the assumption that there was no baseline heterogeneity between the two groups which may not be the case and is therefore a potential source of bias. Second, administration of the SF-36 on only one occasion in the postoperative period does not allow any interpretation of long-term quality-of-life outcomes.

This study reiterates the equivalence of TEP repair with open repair in terms of recurrence, with improved postoperative dysesthesia and chronic pain rates. In addition, quality of life is significantly improved following TEP versus Lichtenstein repair in terms of not only postoperative pain and return to functional status, but in physical role, general health, and emotional role.

References

Eklund AS, Montgomery AK, Rasmussen IC et al (2009) Low recurrence rate after laparoscopic (TEP) and open (Lichtenstein) inguinal hernia repair: a randomized, multicentre trial with 5 year follow up. Ann Surg 249(1):33–38

McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM et al (2003) Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001785

Takata MC, Duh QY (2008) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am 88(1):157–178 x

Kato Y, Yamataka A, Miyano G et al (2005) Tissue adhesives for repairing inguinal hernia: a preliminary study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 15(4):424–428

Hallen M, Bergenfelz A, Westerdahl J (2008) Laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair versus open mesh repair: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 143(3):313–317

Tantia O, Jain M, Khanna S et al (2009) Laparoscopic repair of recurrent groin hernia: results of a prospective study. Surg Endosc 23(4):734–738

The MRC Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Trial Group (1999) Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernia: a randomised comparison. Lancet 354(9174):185-190

Wall ML, Cherian T, Lotz JC (2008) Laparoscopic hernia repair—the best option? Acta Chir Belg 108(2):186–191

Lamb AD, Robson AJ, Nixon SJ (2006) Recurrence after totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair: implications for operative technique and surgical training. Surgeon 4(5):299–307

Wright D, O’Dwyer PJ (1998) The learning curve for laparoscopic hernia repair. Semin Laparosc Surg 5(4):227–232

Toy FK, Moskowitz M, Smoot RT Jr et al (1996) Results of a prospective multicenter trial evaluating the ePTFE peritoneal onlay laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty. J Laparoendosc Surg 6(6):375–386

Vidovic D, Kirac I, Glavan E et al (2007) Laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal hernia repair versus open Lichtenstein hernia repair: results and complications. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 17(5):585–590

Butler RE, Burke R, Schneider JJ et al (2007) The economic impact of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: results of a double-blinded, prospective, randomized trial. Surg Endosc 21(3):387–390

Neumayer L, Jonasson O, Fitzgibbons R et al (2003) Tension-free inguinal hernia repair: the design of a trial to compare open and laparoscopic surgical techniques. J Am Coll Surg 196(5):743–752

Eklund A, Rudberg C, Smedberg S et al (2006) Short-term results of a randomized clinical trial comparing Lichtenstein open repair with totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 93(9):1060–1068

Schmedt CG, Sauerland S, Bittner R (2005) Comparison of endoscopic procedures vs. Lichtenstein and other open mesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Surg Endosc 19(2):188-199

Taylor C, Layani L, Liew V et al (2008) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair without mesh fixation: early results of a large randomised clinical trial. Surg Endosc 22(3):757–762

Gholghesaei M, Langeveld HR, Veldkamp R et al (2005) Costs and quality of life after endoscopic repair of inguinal hernia vs. open tension free repair: a review. Surg Endosc 19(6):816–821

McCormack K, Wake B, Perez J et al (2005) Laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair: systematic review of effectiveness and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 9(14):1–203

de Jonge P, Lloyd A, Horsfall L et al (2008) The measurement of chronic pain and health-related quality of life following inguinal hernia repair: a review of the literature. Hernia 12:561–569

Srsen D, Druzijanic N, Pogorolic Z et al (2008) Quality of life analysis after open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair - retrospective study. Hepatogastroenterology 88:2112–2115

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Myers, E., Browne, K.M., Kavanagh, D.O. et al. Laparoscopic (TEP) Versus Lichtenstein Inguinal Hernia Repair: A Comparison of Quality-of-Life Outcomes. World J Surg 34, 3059–3064 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0730-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0730-y