Abstract

Background

This study was designed to evaluate the clinical and pathologic parameters of benign papillomas diagnosed on core needle biopsy (CNB) and predict malignancy risk after surgical excision.

Methods

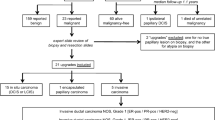

We retrospectively reviewed clinicopathologic findings for 160 CNB-diagnosed benign papillomas followed by surgical excision from 154 patients.

Results

Ten (6.3%) of the excised lesions were diagnosed as malignant. Univariate analysis showed that those that were palpable on physical examination, detected as a mass on mammography, or >1 cm on sonography were significantly associated with malignancy. In multivariate analysis, lesions that were palpable (odds ratio (OR), 29.2; 95% confidence interval (CI), 4.06–209.58; P = 0.001) or detected as a mass (OR, 5.68; 95% CI 1.08–29.87; P = 0.04) remained significantly associated with malignancy. In a CART analysis, including all variables, lesions that were palpable and associated with a mass on mammogram were confirmed as malignant.

Conclusions

Breast lesions diagnosed as benign papillomas on CNB had a 6.3% risk of being malignant. The risk was highest for lesions that were palpable and detectable as a mass on a mammogram. In addition, the low-risk patients avoid immediate surgical excision, although they should be followed carefully.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Papillary lesions of the breast are commonly encountered in surgical pathology and consist of a heterogeneous group from benign papilloma, atypical papilloma, to invasive papillary carcinoma [1]. In case of atypical papilloma on core needle biopsy (CNB), excisional biopsy is recommended to rule out noninvasive and invasive carcinoma. However, it is debatable whether surgical excision should be always performed in benign papilloma on CNB. The risk of underlying malignancy varies 0–36% in basis of reports of surgical excision after a diagnosis of benign papilloma on CNB [2–12].

Distinguishing between benign and malignant papillary lesions based on symptoms and radiologic imaging is problematic. Pathologic confirmations in surgical specimen are essential, because both benign and malignant papilloma can present with bloody nipple discharge [13]. Furthermore, mammographic or sonographic characteristics alone cannot sufficiently distinguish benign from malignant papilloma, because both may present as a mass or calcifications on mammography [14–17]. In this study, we evaluated the clinical and pathologic parameters of benign papilloma diagnosed on CNB and predicted which are associated with malignancy.

Materials and methods

Patients

We reviewed pathologic records of all 4,398 CNB cases performed at the Center for Breast Cancer, National Cancer Center, Korea, between January 2001 and August 2008. A total of 154 patients, who had benign papilloma diagnosed on CNB followed by surgical excision, were included in this study; 6 had bilateral lesions, yielding 160 CNBs for the study. All patients underwent clinical and radiological examination, including bilateral two-view mammography (craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique) and sonography. Palpability was assessed by one of three experienced surgeons, and we characterized the radiological appearance of the lesion according to the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS). Lesion size was based on the greatest dimension measured by sonography. We categorized patients by the following variables: (1) age at the time of CNB diagnosis, (2) presence of nipple discharge, (3) palpability of lesion on physical examination, (4) cytology findings of nipple discharge, (5) size of the largest lesion and number of lesions revealed on sonography, (6) imaging categorization according to BI-RADS classification, (7) location of mass for nipple (central vs. peripheral; criteria, 2 cm from nipple), and (8) mammogram findings (normal, microcalcification, or mass).

Core-needle biopsy and pathology

Sonography-guided biopsies were performed using a spring-loaded device with a 14-gauge automated needle (Bard Peripheral Technologies, Tempe, Arizona). Biopsy tissues and excisional specimens were fixed in formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for pathological assessment and with cytokeratin-5 and high-molecular-weight cytokeratin stain for immunohistochemical analysis. An experienced pathologist (YK) reviewed the slides and categorized them as benign or malignant.

Statistical analysis

To identify factors associated with malignancy, we performed univariate analysis (chi-square test or Student’s t test) and multivariate analysis (logistic regression) using Stata 10.0 for Windows (Texas, USA). A significance level of 0.1 was necessary for a covariate to be entered into multivariate analysis. To investigate which variables were associated with the likelihood of malignancy, we performed classification and regression tree (CART) analysis using Waikato Environment for Knowledge Analysis (version 3.4.10, University of Waikato, New Zealand). We also used the J48 classifier algorithm, which is an implementation of the C4.5 decision tree learner.

Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center at Goyang and complied with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research involving human subjects.

Results

The median patient age was 47 (range, 27–81) years. Table 1 shows the clinicopathologic characteristics of the CNB-diagnosed benign papillary lesions. After surgical excision, ten (6.3%) of the lesions were diagnosed as malignant—four of them in the 45 years or younger age group. Age was not associated with malignancy (P = 0.87).

Ten (6.3%) of the 160 excised lesions were diagnosed as malignant. The diagnoses of the excisional specimens were as follows: 10, showed fibrocystic change; 131, benign papilloma; 9, atypical ductal hyperplasia; 1, ductal carcinoma in situ; 2, intraductal papillary carcinoma; 3, invasive ductal carcinoma; and 4, invasive papillary carcinoma. Table 1 summarizes the diagnosis upgrade rates for all lesions according to clinical, radiological, and pathological variables. Only lesions that were palpable (50% malignant vs. 6.7% benign; P = 0.001), detectable as a mass on mammography (60% malignant vs. 17.3% benign; P = 0.005), or >1 cm on sonography (80% malignant vs. 36.7% benign; P = 0.01) were significantly associated with malignancy. However, location or number of the lesions and BI-RADS in sonography was not related with malignant risk (C4b or C5; 30% malignant vs. 14.7% benign; P = 0.14).

In multivariate analysis, lesions that were palpable (odds ratio (OR), 29.2; 95% confidence interval (CI), 4.06–209.58; P = 0.001) or detectable as a mass (OR, 5.68; 95% CI 1.08–29.87; P = 0.04) were significantly associated with malignancy (Table 2).

Figure 1 presents the results of CART analysis. Palpability together with the presence of a mass on a mammogram was associated with the highest risk of malignancy (4/4, 100%), whereas nonpalpable lesions had the lowest risk (5/145, 3.4%).

Discussion

Many controversies surround the appropriate management of papillary lesions on CNB. In Table 3, current studies for benign papilloma on core needle biopsy are summarized. This study is the largest study for benign papilloma with surgical excision. Additionally, all lesions of this study were preoperatively evaluated by sonography and mammogram. This study demonstrated that 6.3% of benign papillary lesions on CNB revealed malignancy after surgical excision and the risk of malignant risk were higher in the lesions with palpation and mass formation on mammogram. When we reanalyzed these data only for the invasive lesions, the palpable lesions were associated with invasive lesions in multivariate analysis (OR, 28.1; 95% CI 3.64–215.86; P = 0.001, data not shown).

Whether CNB-diagnosed benign papillary lesions should be excised is currently under debate. Some studies conclude that they should be excised because they can become malignant [7, 18] or increase the risk of invasive breast cancers [19, 20], whereas others suggest that excision is not necessary, especially when imaging results agree with the diagnosis [21]. In a recent review of the Mayo Clinic experience with breast papilloma, benign papillary lesions were found to impart a cancer risk similar to that of conventional proliferative fibrocystic change [22].

Some investigators assert that all papillary lesions, with or without associated atypia or malignancy, should be surgically excised [23, 24]. Others, however, assert that a properly performed CNB is adequate for accurate diagnosis, and further surgery is unnecessary [25, 26]. Several studies of large CNBs suggest that lesions without atypia and with concordant imaging classified as BIRADS 4 or a more benign classification do not require excision [4, 25, 27]. Although such studies, with improved lesion categorization, could in theory avoid a substantial number of unnecessary invasive procedures, we found in the present study that benign papillomas classified as BIRADS 3 had a risk of being malignant.

Although we found a greater frequency of malignancy among cases presenting with nipple discharge than in cases presenting without discharge, the difference was not statistically significant. Sakr et al. [17], on the other hand, reported that nipple discharge was significantly associated with malignancy in CNB-diagnosed benign papilloma, and Rizzo et al. [12] reported that asymptomatic papillomas were associated with a higher rate of upgrade than symptomatic ones. Thus, the predictive value of nipple discharge remains unclear.

Conclusions

Breast lesions diagnosed as benign papillomas on CNB had a 6.3% risk of being malignant. The risk was highest for lesions that were palpable and detectable as a mass on a mammogram. In addition, low-risk patients avoid immediate surgical excision, although they should be followed carefully.

References

Rosen PP (1986) Arthur Purdy Stout and papilloma of the breast. Comments on the occasion of his 100th birthday. Am J Surg Pathol 10:100–107

Berg WA (2004) Image-guided breast biopsy and management of high-risk lesions. Radiol Clin North Am 42:935–946

Reynolds HE (2000) Core needle biopsy of challenging benign breast conditions: a comprehensive literature review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 174:1245–1250

Ivan D, Selinko V, Sahin AA et al (2004) Accuracy of core needle biopsy diagnosis in assessing papillary breast lesions: histologic predictors of malignancy. Mod Pathol 17:165–171

Liberman L, Bracero N, Vuolo MA et al (1999) Percutaneous large-core biopsy of papillary breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 172:331–337

Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Singer C et al (2001) Papillary lesions of the breast: evaluation with stereotactic directional vacuum-assisted biopsy. Radiology 221:650–655

Ciatto S, Andreoli C, Cirillo A et al (1991) The risk of breast cancer subsequent to histologic diagnosis of benign intraductal papilloma follow-up study of 339 cases. Tumori 77:41–43

Agoff SN, Lawton TJ (2004) Papillary lesions of the breast with and without atypical ductal hyperplasia: can we accurately predict benign behavior from core needle biopsy? Am J Clin Pathol 122:440–443

Ashkenazi I, Ferrer K, Sekosan M et al (2007) Papillary lesions of the breast discovered on percutaneous large core and vacuum-assisted biopsies: reliability of clinical and pathological parameters in identifying benign lesions. Am J Surg 194:183–188

Liberman L, Tornos C, Huzjan R et al (2006) Is surgical excision warranted after benign, concordant diagnosis of papilloma at percutaneous breast biopsy? AJR Am J Roentgenol 186:1328–1334

Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Oken SM et al (2006) Papillary lesions of the breast at percutaneous core-needle biopsy. Radiology 238:801–808

Rizzo M, Lund MJ, Oprea G et al (2008) Surgical follow-up and clinical presentation of 142 breast papillary lesions diagnosed by ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 15:1040–1047

Cardenosa G, Eklund GW (1991) Benign papillary neoplasms of the breast: mammographic findings. Radiology 181:751–755

Soo MS, Williford ME, Walsh R et al (1995) Papillary carcinoma of the breast: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 164:321–326

Haagensen CD, Stout AP, Phillips JS (1951) The papillary neoplasms of the breast. I. Benign intraductal papilloma. Ann Surg 133:18–36

Woods ER, Helvie MA, Ikeda DM et al (1992) Solitary breast papilloma: comparison of mammographic, galactographic, and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 159:487–491

Sakr R, Rouzier R, Salem C et al (2008) Risk of breast cancer associated with papilloma. Eur J Surg Oncol 34:1304–1308

Papotti M, Eusebi V, Gugliotta P et al (1983) Immunohistochemical analysis of benign and malignant papillary lesions of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 7:451–461

Carter D (1977) Intraductal papillary tumors of the breast: a study of 78 cases. Cancer 39:1689–1692

Moore SW, Pearce J, Ring E (1961) Intraductal papilloma of the breast. Surg Gynecol Obstet 112:153–158

Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Tizol-Blanco DM et al (2004) Papillomas and atypical papillomas in breast core needle biopsy specimens: risk of carcinoma in subsequent excision. Am J Clin Pathol 122:217–221

Lewis JT, Hartmann LC, Vierkant RA et al (2006) An analysis of breast cancer risk in women with single, multiple, and atypical papilloma. Am J Surg Pathol 30:665–672

Hoda SA, Rosen PP (2006) Observations on the pathologic diagnosis of selected unusual lesions in needle core biopsies of breast. Breast J 10:522–527

Valdes EK, Tartter PI, Genelus-Dominique E et al (2006) Significance of papillary lesions at percutaneous breast biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 13:480–482

Philpotts LE, Shaheen NA, Jain KS et al (2000) Uncommon high-risk lesions of the breast diagnosed at stereotactic core-needle biopsy: clinical importance. Radiology 216:831–837

Carder PJ, Garvican J, Haigh I et al (2005) Needle core biopsy can reliably distinguish between benign and malignant papillary lesions of the breast. Histopathology 46:320–327

Rosen EL, Bentley RC, Baker JA et al (2002) Imaging-guided core needle biopsy of papillary lesions of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol 179:1185–1192

Ahmadiyeh N, Stoleru MA, Raza S et al (2009) Management of intraductal papillomas of the breast: an analysis of 129 cases and their outcome. Ann Surg Oncol 16:2264–2269

Sakr R, Rouzier R, Salem C et al (2008) Risk of breast cancer associated with papilloma. Eur J Surg Oncol 34:1304–1308

Sydnor MK, Wilson JD, Hijaz TA et al (2007) Underestimation of the presence of breast carcinoma in papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core-needle biopsy. Radiology 242:58–62

Plantade R, Gerard F, Hammou JC (2006) Management of non malignant papillary lesions diagnosed on percutaneous biopsy. J Radiol 87:299–305

Puglisi F, Zuiani C, Bazzocchi M et al (2003) Role of mammography, ultrasound and large core biopsy in the diagnostic evaluation of papillary breast lesions. Oncology 65:311–315

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, SY., Kang, HS., Kwon, Y. et al. Risk Factors for Malignancy in Benign Papillomas of the Breast on Core Needle Biopsy. World J Surg 34, 261–265 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-009-0313-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-009-0313-y