Abstract

Background

Palliative surgery for the treatment of incurable obstructive colorectal carcinoma is associated with a considerable perioperative morbidity and mortality but no substantial improvement of the prognosis. The aim of the present study was to study the effectiveness of colorectal stenting compared with palliative surgery in incurable obstructive colorectal carcinoma.

Patients and Methods

From April 1999 to April 2005, data of consecutive patients with incurable stenosing colorectal carcinoma, either treated with stent implantation or palliative surgical intervention, were prospectively recorded with respect to age, sex, tumor location (including metastases), ASA-score, peri-interventional morbidity, mortality, rates of complications, and re-interventions as well as survival.

Results

Of 40 patients, 38 (95%) were successfully treated with a stent. Two patients (5%) underwent surgical intervention after stent dislocation. In contrast, 38 patients primarily underwent palliative surgical intervention. Stent patients were significantly older (P = 0.020), had a higher ASA-score (P = 0.012), and had more frequently distant metastases (P = 0.011). After successful stent implantation, no early complications were observed, but late complications occurred in 11 subjects (29%). Following palliative surgical intervention, postoperative complications occurred in 12 individuals (32%) . Postoperative mortality was 5% in the surgery group, whereas no patient died following stent implantation. There was no significant differences in the survival of both groups (9.9 vs. 7.8 months, respectively; log rank: 0.506).

Conclusions

Palliative treatment of incurable obstructive colorectal carcinoma using stents is an effective and suitable alternative to palliative surgery with no negative impact on the survival but less peri-interventional morbidity and mortality as well as comparable overall morbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In incurable obstructive colorectal carcinoma, palliative resection of the primary tumor has been considered the treatment of choice. The only aim of this symptomatic treatment is the elimination of tumor-associated symptoms, such as hemorrhage, obstruction, and/or perforation, which can result in an improvement or preservation of the patient’s quality of life but which also involves the associated disease-specific and treatment-related risks. With respect to palliative surgical interventions in colorectal carcinomas, data obtained from the literature indicate an intervention-related morbidity and mortality of 5–15% and 0–30%, respectively, as well as a median survival of 4–17 months in UICC stage IV tumor lesions.1–11 In recent years, the implantation of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) has been established as an alternative therapeutic option—in particular in patients at high surgical risk or with locally unresectable colorectal carcinomas. The reported intervention-related morbidity and mortality are appreciably lower than in palliative surgical interventions.1–3,12–18 Data on median survival after stent implantation have been reported to vary considerably, ranging from 2–11 months.1–3,13,14,19,20 However, as patients with stent implantation need to be considered a negative selection with high surgical risk, a direct (risk-related) comparison of patients undergoing stent implantation with those undergoing palliative surgical intervention is not possible. There have been some reports in which prospective randomized investigations have been limited to small groups of patients,2,19 while other investigators have compared patients with SEMS with those of historical control groups.1,3

The objective of this study was to investigate endoscopic stent implantation in the palliative treatment of obstructive, incurable colorectal carcinoma as an alternative to surgical intervention.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between April 1999 and April 2005, all consecutive patients with incurable stenosing colorectal carcinoma in the Department of Surgery at the Carl-Thiem Hospital, Cottbus (Germany) were enrolled in this prospective, nonrandomized, unicenter observational study. We prospectively recorded who had been treated with SEMS (Group I) or who had undergone palliative surgical intervention (resection, intestinal bypass, creation of a colostomy) (Group II) because of an unresectable colorectal carcinoma. The prospective collection of data was carried out within the framework of a Germany-wide quality control study for primary colorectal carcinomas conducted at the Institute for Quality Control in Operative Medicine at the Otto-von-Guericke University, Magdeburg. The study design and monitoring protocols have been described elsewhere.21,22

The assignment of patients to Group I or Group II was based solely on the assessment of general or local operability. In addition, patients declining any kind of surgery were assigned to Group I. Patients with palliative chemotherapy were excluded completely.

Group I (SEMS Implantation)

High-risk patients (ASA-score IV) and/or locally unresectable [computerized tomography (CT) findings] patients with a stenosing colorectal carcinoma located between the ileoceacal valve and 5 cm above the anocutaneous line (ACL) with manifest obstruction were treated with a SEMS placement. Manifest obstruction was defined by clinical or radiological signs of disordered transit characterized by prestenotic colonic dilatation or visible air-fluid level.

The stent was implanted using an endoscopic/radiological rendezvous technique after the patient had been admitted to hospital. After receiving a cleansing enema, the patient was positioned on a fluoroscopic table and, under sedation, first examined with a small-caliber endoscope. If it proved possible to pass this scope through the stenosing tumor lesion, its luminal extent was accurately determined under endoscopic and fluoroscopic control to determine the required length of the stent. Subsequently, a guide wire was introduced. If it was impossible to maneuver the endoscope through past the tumor lesion, a guide wire with a hydrophilic tip was inserted under fluoroscopic control, and the extent of the stenosis could then be visualized by applying contrast medium via an ERCP catheter. The stenosis was not dilated or recanalized. A stiffer guide wire was inserted, and the small-caliber endoscope was replaced by a treatment endoscope with a 3.6- to 4.2-mm working channel, which was passed over the wire to permit SEMS application “through the scope” under fluoroscopic control.

For documentation purposes of the clinical outcome and the correct positioning of the stent, we routinely performed a clinical examination and radiological check (plain abdominal X-ray) on the following day. If there was a relief of the obstructive symptoms, the patient was able to quickly return to normal alimentation and was subsequently discharged; subsequent follow up and checks were carried out in an outpatient clinic setting. Continual utilization of laxatives was mandatory. The patient underwent routine follow-up examinations at 4- to 8-week intervals. The stent types implanted are listed in Table 1.

Group II (Surgery)

Palliative surgical interventions (continuity resection or discontinuity resection, intestinal bypass, creation of a colostomy) were indicated in patients with locally unresectable tumor growth. If the carcinoma proved unresectable, either an intestinal bypass or a colostomy was constructed, depending on the location of the tumor lesion. Patients with unresectable carcinoma of the rectum and sigmoid colon were given a loop sigmoid stoma.

The decision for stent-implantation or surgery was exclusively made by three surgeons with extensive expertise in colorectal surgery and endoscopic procedures. These surgeons performed the selected procedures.

Both patient groups were characterized by age, sex, location of the carcinoma, palliative indication, metastases, local resectability, and ASA classification. Peri-interventional morbidity and mortality, postoperative complications, re-interventions, and survival times were compared between both patient groups. In the SEMS group, colonic perforation, transfusion-requiring tumor bleeding, re-obstruction, stent migration and stent fracture were considered to be the relevant postinterventional complications. In the group with palliative surgical intervention, the postoperative complications were differentiated into general and specific complications.

In terms of the reasons for incurability of the cancer disease (distant metastases, local irresectability ), each of the two groups contained an inhomogeneous collection of patients. For the analysis and comparison of survival times, therefore, each group was additionally subdivided into a subgroup with metastasizing colorectal carcinoma (Group Ia) and a subgroup without metastases (Group Ib). The group of surgical patients was subdivided into a subgroup of palliatively resected patients with distant metastases (Group IIa) and a subgroup with no distant metastases and no tumor resection, in whom an intestinal bypass or a stoma was performed (Group IIb). For the comparison of survival, both Group I versus Group II and, separately, the metastasizing and nonmetastasizing subgroups (Group Ia vs. Group IIa; Group Ib vs. IIb) were compared.

Statistical Analysis

For the comparison of continuous variables, the t-test was used. Two-dimensional frequency distributions were compared using the chi-squared test. For the analysis of survival, the Kaplan-Meier method with log rank test was used to compare the patient groups for a significantly different survival probability.

RESULTS

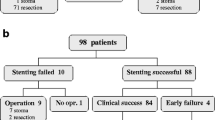

Within the observation period, stent implantation was indicated in 40 patients, of whom 38 (95%) were successfully treated (SEMS group). In two of these patients, the stent migrated immediately, and the patients were subsequently excluded from the study. Peri-interventional complications did not occur. All of the patients experienced a relief of their obstructive symptoms and were discharged on the second or third day after implantation.

During the same period, 38 patients were submitted to surgical treatment. In 19 cases (50%), a palliative resection of the carcinoma was performed, while the remaining 19 patients (50%) with an unresectable carcinoma received an intestinal bypass (n = 4; 10%) or a colostomy (n = 15; 40%).

Demographics

The mean age of the patients with SEMS implantation was 77.7 years (range: 47–96 years; median age: 79 years), while that of the patients with palliative surgical intervention was 73.6 years (range: 50–86 years; median age: 74 years). This difference was significant at P = 0.020 . The two patient groups also differed significantly in terms of the ASA classification, with the score being significantly higher in the patients of Group I than in those of Group II (P = 0.012). In Group I, 15 of the 38 patients (40%) showed a metastasizing tumor growth at the time of the diagnosis, while in Group II, metastases were detected in 26 of the 38 patients (68%).

With respect to the distribution of the primary tumor sites, the two groups of patients were comparable (Table 2). Although tumor lesions in the caecum and descending colon were more common in the surgical group, the difference was not significant (P = 0.191).

Morbidity, Mortality, Hospital Stay

None of the patients of Group I who were successfully treated by endoscopic intervention developed post-interventional complications; all 38 patients revealed a clinical improvement in obstructive symptoms within 48 h. The median in situ duration of the implanted stents in this group was 160 days (= 5.3 months; range: 8–971 days; mean: 268.9 days).

Over the long-term course of this study, 11 of these 38 patients (29%) developed problems. In five of these (5/38; 13%) patients the problems were amenable to endoscopic treatment, but a palliative surgical intervention was necessary in two of the 38 patients (5%; right hemicolectomy, n = 1; sigmoideal resection, n = 1; Table 3). There were no peri-operative complications in these latter two patients. In the remaining four patients, no re-interventions became necessary, and no signs of a re-obstruction were seen up to patient’s death or up to the time point of this analysis. During the follow-up investigation period, there were no intervention-associated deaths.

In Group II, all patients experienced an immediate relief of their obstructive symptoms. Of the operated 38 patients, 12 (32%) developed relevant postoperative complications (Table 4): seven patients (3/38; 18%) had general complications, while five patients (5/38; 13%) had specific complications.

Postoperative complications were less frequent in patients of Group IIa than in patients of Group IIb (26 vs. 37%), but two patients of Group IIa died from their complications, resulting in a postoperative mortality 10%. The overall mortality of the patients in Group II was 5%. Follow-up complications which required re-intervention were not seen in Group II.

There was a significantly shorter median postinterventional hospital stay in Group I patients (range: 1–3 days; median: 2 days) than in Group II patients (range: 7–15 days; median: 9.5 days; P < 0.0001).

Survival

Follow-up data were available for all Group I patients. Twenty-eight patients had already died from their malignant disease by the time of the analysis. The median survival time of the deceased patients was 315.5 days (= 10.5 months; range: 15–994 days); the median survival time of all patients was 296 days (=9.9 months; mean: 451 days).

The survival rate of patients in Group Ia was 208 days (=6.9 months; median: 332 days) versus 511 days (=17.0 months; mean: 321 days) in the patients of Group Ib.

In the surgical group, follow-up data were available for 34 of the 38 patients (89%). Thirty-two of the 34 patients had died by the time of the evaluation. The median survival was 234 days (=7.8 months; range: 8–1,451 days).

The median survival of Group IIa patients was 513 days (=17.1 months; mean: 512 days) versus only 168 days (=5.6 months; mean: 289 days) for those in Group IIb. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for the Group I versus Group II comparison. There was no significant difference between the survival of patients of Group I and that of patients of Group II (log rank, P = 0.506), between the survival of patients of Group Ia and that of patients of Group IIa (log rank, P = 0.439), or between the survival of patients of Group Ib and that of patients of Group IIb (log rank, P = 0.084). However, patients of Group Ib tended to survive slightly longer than those in Group IIb (median: 321 vs. 168 days).

DISCUSSION

In patients with colorectal carcinoma, incurable tumor disease can be caused by distant metastases, locally unresectable tumor growth, or serious comorbidities that do not permit an oncologically adequate resection of the tumor lesion with an acceptable perioperative risk. Accordingly, patients with such incurable tumor disease can be considered to be an inhomogeneous group. However, there is one characteristic in common, namely, the aim for an improvement of symptoms by palliative intervention despite leaving the tumor lesion in situ. To date, no general recommendations have been established with regard to the optimal therapeutic procedure based on a defined situation, and the subject remains a matter of controversy.6–10,23

In the prospective, single-center, and nonrandomized study reported here, patients with incurable colorectal carcinomas were compared in terms of the outcome after operative versus endoscopic interventional management of the tumor-associated obstruction. The significant differences between surgically and endoscopically treated patients in terms of age (P = 0.020) and ASA classification (P = 0.012), with a preponderance of older and multimorbid patients in Group I, are a consequence of the negative selection based on risk-related decision-making for an endoscopic or surgical treatment. With regard to sex ratio and distribution of tumor locations, however, no differences were found.

The analysis presented here mainly focused on the survival of the patients in the different groups. For the patients undergoing palliative surgical intervention (median: 7.8 months)—in particular, palliative resection (median: 17.1 months)—survival was not longer than that of endoscopically treated patients (median: 9.9 months; log rank: 0.506), a result which is in agreement with those reported by other investigators.1,4,6,8–10

Previous investigations have generally compared endoscopic treatment and the construction of a stoma,2,3,19 while only a few studies have also included palliative resections.1 The median survival times have ranged from 3.0 to 7.5 months and from 3.9 to 4.9 months, respectively, for endoscopic and surgical palliative interventions. As shown in our study, there was only a tendency for SEMS implantation to provide a longer survival time in comparison with stoma construction.

The survival of patients with an incurable carcinoma depends to a large extent on the patient’s age and the tumor volume left in situ. In a retrospective analysis of 120 patients with incurable nonobstructive colorectal carcinoma (UICC-IV) who underwent laparotomy, Rosen et al. showed that asymptomatic patients older than 65 years and patients with extensive liver metastases gain no benefit from palliative tumor resection.6 Ruo et al. also compared UICC-IV patients with no tumor resection (n = 103) with patients undergoing palliative resection (n = 127).10 These investigators found that the longer survival of the palliatively resected patients was caused by the significantly more extensive hepatic and extrahepatic metastatic tumor growth in the other patient group with no resection, which they identified as an independent prognostic factor for survival in the multivariate regression analysis. These authors recommended that the decision-making for a palliative resection in asymptomatic patients should be based on the metastatic burden and the patient’s clinical status. Other authors also consider palliative resection in UICC-IV patients with extensive metastases as a reasonable option, but only if tumor-related complications are present.8,9 The survival rates of patients having undergone palliative resection (median: 10–16 months) reported by these authors are comparable with our data.

Despite this, intervention-related morbidity and mortality acquire greater weight in the decision-making for a palliative intervention. When endoscopic intervention is compared with open surgery, not only do differences in the type and frequency of complications need to be taken into account, but also differences in the time points of their occurrence. This makes a proper comparison difficult. Our results for palliative surgical intervention largely reflect those reported in the literature—for example, a mortality up to 30% and a morbidity of up to 50%;1–11 these figures are considerably higher than those reported for endoscopic procedures: 2% and 30%, respectively.1–3,12–14,16–18 Endoscopic interventions may be expected to cause only a low complication rate in the short-term postinterventional course. However, these patients often develop problems in the intermediate or long-term course; in our investigation, the complication rate was 30%, which is comparable to data reported in the literature.1,14,17 Although most of the complications could be managed endoscopically–– or even needed no further measures—5% of the patients required surgical treatment. In the SEMS group, we found no method-related deaths, neither in the peri-interventional period nor in the later course.

To avoid complications after SEMS (stent dislocation or stent obstruction), it is indispensable to take laxatives as permanent medication.

Although the perioperative morbidity of 32% observed in the surgical group is comparable with the follow-up morbidity of the SEMS patients, two patients died of their complications, resulting in a surgery-related mortality of 5%.

In a prospective multicenter observational study in which 3,756 patients were enrolled, Marusch et al. investigated the impact of age on the complication rate of surgical intervention in colorectal carcinoma. They found that the rate of general complications significantly increased with age—in particular, in emergency cases—whereas the rate of specific complications was not different.24 In view of the greater morbidity and mortality of the multimorbid elderly patients with acute colorectal obstruction in comparison with the elective situation, these patients benefit from every successful nonsurgical measure, which, in the case of SEMS in the incurable patient, may also represent definitive palliative treatment.

In summary, the data show that, in comparison with SEMS as an endoscopic palliative intervention, surgical palliative intervention for incurable colorectal carcinoma—in particular in patients of advanced age—provide no significant advantages. Therefore, SEMS can be considered to be a reasonable alternative that increases the therapeutic spectrum and flexibility of decision-making in high-risk patients with unresectable colorectal tumor growth. In particular, such patients with locally unresectable tumor growth may benefit from the endoscopic intervention, since it avoids—if there is no complication—the construction of a colostomy, which previously was one of the few treatment options available; consequently the patient’s quality of life is preserved. In addition, SEMS shortens the hospital stay and recovery in comparison with an intestinal bypass.1,3 However, in the present study, the limited number of patients and the selection bias (high percentage of multimorbid and older patients in the SEMS group) as a result of the nonrandomized study design must be taken into account. This means that larger patient groups investigated in a prospective multicenter study might possibly provide still more relevant data on the subject.21,22

References

Carne PW, Frye JN, Robertson GM, et al. Stents or operation for palliation of colorectal cancer: a retrospective, cohort study of perioperative outcome and long-term survival. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:1455–1461

Fiori E, Lamazza A, De Cesare A, et al. Palliative management of malignant rectosigmoidal obstruction. Colostoma vs. endoscopic stenting. A randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res 2004;24:265–268

Johnson R, Marsh R, Corson J, et al. A comparison of two methods of palliation of large bowel obstruction due to irremovable colon cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2004;86:99–103

Joffey J, Gordon PH. Palliative resection for colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 1981;24:355–360

Wabeno HJ, Semoglou C, Attiyeh F, et al. Surgical management of patients with primary operable colorectal cancers and synchronous liver metastasis. Am J Surg 1978;135:81–85

Rosen SA, Buell JF, Yoshida A, et al. Initial presentation with stage IV colorectal cancer. How aggressive should we be? Arch Surg 2000;135:530–535

Makela J, Haukipuro K, Laitinen S, et al. Palliative operations for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 1990;33:846–850

Liu SK, Church JM, Lavery IC, et al. Operations in patients with incurable colon cancer — is it worthwhile? Dis Colon Rectum 1997;40:11–14

Scoggins CR, Meszoely IM, Blanke CD, et al. Nonoperative management of primary colorectal cancer in patients with stage IV disease. Ann Surg Oncol 1999;6:651–657

Ruo L, Gougoutas C, Paty PB, et al. Elective bowel resection for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: prognostic variables for asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:722–728

Gastinger I, Marusch F, Koch A, et al. Hartmann’s procedure indication in colorectal carcinoma. Chirurg 2004;75:1191–1196

De Gregorio MA, Mainar A, Tejero E, et al. Acute colorectal obstruction: stent placement for palliative treatment—results of a multicenter study. Radiology 1998;209:117–120

Bhardwaj R, Parker MC. Palliative therapy of colorectal carcinoma: stent or surgery? Colorectal Dis 2003;5:518–521

Aviv RI, Shyamalan G, Watkinson A, et al. Radiological palliation of malignant colonic obstruction. Clinical Radiol 2002;57:347–351

Suzuki N, Sauders BP, Thomas-Gibson S, et al. Colorectal stenting for malignant and benign disease: outcomes in colorectal stenting. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:1201–1207

Law WL, Choi HK, Lee YM, et al. Palliation for advanced malignant colorectal obstruction by self-expanding metallic stents: Prospective evaluation of outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:39–43

Khot UP, Lang AW, Murali K, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of colorectal stents. Br J Surg 2002;89:1096–1102

Meisner S, Hensler M, Knop FK, et al. Self-expanding metal stents for colonic obstruction: Experiences from 104 procedures in a single center. Dis Colon Rectum 2004;47:444–450

Xinopoulos D, Dimitroulopoulos D, Theodosopoulos T, et al. Stenting or stoma creation for patients with inoperable malignant colonic obstructions ? Results of a study and cost-effectiveness analysis. Surg Endosc 2004;18:421–426

Seymour K, Johnson R, Marsh R, et al. Palliative stenting of malignant large bowel obstruction. Colorectal Dis 2002;4:240–245

Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Importance of rectal extirpation for the therapy concept of low rectal cancers. Chirurg 2003;74:341–351

Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. "Colon-/rectal carcinoma" prospective studies as comprehensive surgical quality assurance. Chirurg 2002;73:138–145

Fazio VW. Indications and surgical alternatives for palliation of rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:262–265

Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Impact of age on the short-term postoperative outcome of patients undergoing surgery for colorectal carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis 2002;17:177–184

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ptok, H., Marusch, F., Steinert, R. et al. Incurable Stenosing Colorectal Carcinoma: Endoscopic Stent Implantation or Palliative Surgery?. World J. Surg. 30, 1481–1487 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0513-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0513-z