Abstract

Purpose

To determine the need for a standardized renal mass reporting template by analyzing reports of indeterminate renal masses and comparing their contents to stated preferences of radiologists and urologists.

Methods

The host IRB waived regulatory oversight for this multi-institutional HIPAA-compliant quality improvement effort. CT and MRI reports created to characterize an indeterminate renal mass were analyzed from 6 community (median: 17 reports/site) and 6 academic (median: 23 reports/site) United States practices. Report contents were compared to a published national survey of stated preferences by academic radiologists and urologists from 9 institutions. Descriptive statistics and Chi-square tests were calculated.

Results

Of 319 reports, 85% (271; 192 CT, 79 MRI) reported a possibly malignant mass (236 solid, 35 cystic). Some essential elements were commonly described: size (99% [269/271]), mass type (solid vs. cystic; 99% [268/271]), enhancement (presence vs. absence; 92% [248/271]). Other essential elements had incomplete penetrance: the presence or absence of fat in solid masses (14% [34/236]), size comparisons when available (79% [111/140]), Bosniak classification for cystic masses (54% [19/35]). Preferred but non-essential elements generally were described in less than half of reports. Nephrometry scores usually were not included for local therapy candidates (12% [30/257]). Academic practices were significantly more likely than community practices to include mass characterization details, probability of malignancy, and staging. Community practices were significantly more likely to include management recommendations.

Conclusions

Renal mass reporting elements considered essential or preferred often are omitted in radiology reports. Variation exists across radiologists and practice settings. A standardized template may mitigate these inconsistencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Renal masses are commonly detected as incidental findings on imaging examinations performed for unrelated indications [1,2,3,4,5,6]. When an incidentally detected mass cannot be characterized as benign or as having a very low likelihood of malignancy, further imaging is obtained to evaluate the mass and to determine the probability that the mass is malignant [5,6,7,8,9]. This imaging usually is performed with CT or MRI using a protocol designed specifically to evaluate renal masses (typically with and without intravenous contrast material) [10, 11]. Results of these exams allow masses to be considered either definitively benign (i.e., Bosniak I simple cysts, Bosniak II benign complicated cysts, classic angiomyolipomas, other [e.g., hematoma]), or possibly malignant (i.e., Bosniak IIF, Bosniak III, and Bosniak IV cystic masses, and solid masses without macroscopic fat) [5,6,7,8].

Based on the results of a recently reported national survey of urologists and abdominal radiologists, the radiology reports of these renal mass protocol CT and MRI examinations should include certain essential elements [12]. These include the presence or absence of enhancement, the presence or absence of macroscopic fat, mass size, mass type (i.e., cystic vs. solid), use of the Bosniak classification system for cystic masses, size comparison(s) if feasible, and radiologic cancer staging for solid masses without macroscopic fat and for Bosniak III and IV cystic masses [5,6,7,8, 12]. However, the consistency and manner with which these essential and less necessary elements [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] are reported are unknown.

We have anecdotally observed that wide variation exists among and between community and academic radiologists’ reports, and that necessary elements (e.g., use of the Bosniak classification of cystic masses) are often omitted. If this observation is confirmed in a wide systematic review, it would demonstrate that steps are needed to minimize variation and improve communication. The purpose of our study was to determine the need for a standardized renal mass reporting template by analyzing reports of indeterminate renal masses and comparing their contents to stated preferences of radiologists and urologists [12].

Methods

A multi-institutional study was performed. The host institutional review board waived regulatory oversight for this ongoing Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant quality improvement effort. No extramural funding was used.

Study population

Radiology reports of CT and MR examinations performed to characterize a renal mass were solicited from 6 academic practices and 6 community practices. Due to inevitable overlap in practice types, “academic” was loosely defined as practices that have primary research and education missions, and “community” was loosely defined as practices that emphasize clinical care, recognizing that many practices emphasize these three missions to a greater or lesser degree. Each practice was asked to provide the study team 30 reports from consecutive CT or MR examinations performed with and without contrast material for the purpose of characterizing a renal mass from 2014 to 2017 (i.e., these represented the inclusion criteria). The academic practices were selected based on membership in the Society of Abdominal Radiology Disease-Focused Panel on Renal Cell Carcinoma (SAR DFP on RCC) and the community practices were selected based on membership in the Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative (MUSIC). These organizations were targeted because they have a stated interest in improving the care of patients with renal masses and have membership representation who could facilitate the acquisition of the needed reports.

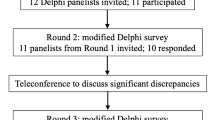

Protected health information was removed from the reports prior to analysis. Each report was manually reviewed by two senior radiology residents to confirm that the inclusion criteria were met and to record the individual elements contained in each report. Of 360 reports submitted to the study team, 40 were not analyzed because they did not meet inclusion criteria. From the 320 reports that met the inclusion criteria, one was excluded because it described a perirenal lymphangioma (i.e., not a renal mass). The remaining 319 reports were separated into two types: those that characterized a mass as definitively benign (N = 48; i.e., Bosniak I simple cyst, Bosniak II benign complicated cyst, classic angiomyolipoma, other definitively benign finding [e.g., hematoma]) and those that characterized a mass as possibly malignant (N = 271; i.e., Bosniak IIF, Bosniak III, Bosniak IV, solid without macroscopic fat) [5,6,7,8]. The study population flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Systematic review of 320 CT or MRI reports of an indeterminate renal mass: study population flowchart. For reports in which a cystic mass was not assigned a Bosniak classification, the Bosniak classification was inferred based on the features described. The distribution of possibly malignant masses was not significantly different between academic and community practices (p = 0.12)

Report analysis: possibly malignant masses

The contents of each radiology report describing a possibly malignant mass (N = 271) were coded by two senior radiology residents enrolled in an advanced quality improvement training program. Supervision and periodic quality assurance of their work were provided by a fellowship-trained abdominal radiologist with expertise in renal mass imaging and 6 years of faculty experience. The following elements were coded (domain levels were not necessarily mutually exclusive).

-

1.

Examination type: CT, MRI, with contrast material, without contrast material, with and without contrast material, not reported

-

2.

Mass type: cystic, solid without macroscopic fat, solid with macroscopic fat, mass unable to be characterized, not reported

-

3.

Mass size, including methods: reported, not reported, largest diameter, bi-directional, tri-planar, volume

-

4.

Size comparison: eligible comparison(s) listed and used, eligible comparison(s) listed and not used, eligible comparison(s) not listed

-

5.

Enhancement, including methods: reported (presence or absence), not reported, reported qualitatively, reported quantitatively (e.g., by magnitude of change in signal intensity or Hounsfield Units comparing enhanced and unenhanced scans), whether it is specifically stated that a portion or all of the mass enhances

-

6.

Macroscopic fat: reported (presence or absence), not reported, not applicable (i.e., cystic mass)

-

7.

Mass margins: reported (circumscribed vs. infiltrative), not reported

-

8.

Necrosis: reported (presence or absence), not reported, not applicable (i.e., cystic mass)

-

9.

Bosniak classification, including method: reported, not reported, not applicable (i.e., solid mass), whether individual Bosniak classification features were included

-

10.

Nephrometry score [21], including method: reported, not reported, not applicable (i.e., not a T1a or T1b mass, presence of tumor thrombus, or evidence of metastasis), overall score reported, individual components of the score reported, descriptions of the individual components of the score reported

-

11.

Estimated probability of malignancy, including method: reported, not reported, expressed qualitatively, expressed quantitatively

-

12.

Features predictive of indolent growth (solid masses only; e.g., hypointensity on T2-weighted images, homogenous hyperattenuation on unenhanced CT) [22], including method: reported (presence or absence), not reported

-

13.

Lymph node size, including method: enlarged node reported, no enlarged node reported, enlarged node described qualitatively, enlarged node measured in short-axis diameter only, enlarged node measured in short- and long-axis diameters

-

14.

Tumor thrombus (i.e., tumor in vein), including method: reported (presence or absence), not reported, concomitant bland thrombus reported (presence or absence), concomitant bland thrombus not reported, reported with description of vessels involved, reported with description of vessels involved, and one or more of the following measurement(s):

-

a.

Overall length of tumor thrombus

-

b.

Distance to gonadal vein

-

c.

Distance to adrenal vein

-

d.

Distance from thrombus in vein to crossing superior mesenteric artery

-

e.

Distance to inferior vena cava

-

f.

Length within inferior vena cava

-

g.

Distance to hepatic veins

-

h.

Distance to diaphragm

-

i.

Distance to right atrium

-

a.

-

15.

The following were coded as reported or not reported. Items ‘a’ through ‘e’ were recorded only for potential nephron-sparing surgery candidates (i.e., T1a or T1b mass, no tumor thrombus, no evidence of metastasis)

-

a.

Axial location (e.g., anterior, posterior)

-

b.

Capsular location (e.g., endophytic, exophytic, mesophytic)

-

c.

Distance to sinus fat

-

d.

Distance to collecting system

-

e.

Position relative to polar lines

-

f.

Histologic differential diagnosis

-

g.

Management options mentioned

-

h.

Percutaneous biopsy mentioned

-

i.

Percutaneous ablation mentioned

-

j.

Follow-up interval mentioned

-

k.

Follow-up imaging method mentioned

-

l.

Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging reported

-

a.

The three study team members involved in coding reviewed the above schema prior to data entry. Next, both senior radiology residents individually reviewed 10 random reports and then all three members discussed the results of those 20 reports (10 + 10) in consensus. This was repeated for another 20 random reports. The purpose of these steps was to create consensus around the coding schema. Following that, periodic quality assurance was performed as the remaining reports were analyzed. Size comparisons were considered “eligible” only if the comparison exam(s) were referenced somewhere in the report and was/were greater than 1 month older than the index report. If there was no tumor thrombus reported, bland thrombus was not assessed. If the mass was cystic and no Bosniak classification was assigned, the Bosniak classification was inferred based on the features listed in the report. This inferred Bosniak classification was used in Table 1 to summarize the types of masses that were reviewed. Otherwise, it was ignored.

The following post hoc analyses were performed. All reports were coded according to their use of structured formatting: (1) free-text report body, (2) organ-based structure in report body, (3) renal mass-specific template in report body. If multiple codes applied, the highest number code was used. All recommendations included in reports were coded by the strength of language used to make those recommendations: (1) optional language (e.g., “may,” “consider,” “option[-al],” “could”), (2) suggestive language (“suggest[-ed]”), and (3) prescriptive language (e.g., “should,” “recommend,” “is advised”). If multiple codes applied, the highest number code was used.

Report analysis: definitively benign masses

Reports describing definitively benign masses were analyzed for the following secondary outcomes: (1) whether the Bosniak classification was used for benign cystic masses, (2) the method used to report a Bosniak I simple cyst, (3) the method used to report a Bosniak II benign complicated cyst, and (4) whether macroscopic fat was described in a report that diagnosed classic angiomyolipoma.

Data analysis

Proportions were summarized with counts and percentages. The distribution of possibly malignant masses described in the community and academic reports were compared using a 2 × 4 Chi -square test. The primary outcome was an analysis of reporting methods in the overall population (academic + community) for reports that described a possibly malignant mass (N = 271). The goal was to identify elements reported greater than 90% of the time. Assuming 80% power, alpha 0.05, and 250 total reports, observed proportions 94% or greater were statistically likely to be reported greater than 90% of the time. Differences in reporting methods by practice type and methods of reporting definitively benign masses were explored as secondary outcomes. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the reporting of academic and community radiology practices. Due to the number of hypothesis tests performed, p < 0.01 was considered statistically significant. Elements considered ‘essential’ and ‘preferred’ were defined in Ref. [12] and are annotated in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Results

The final study population included 319 radiology reports (220 CT without and with IV contrast; 99 MR without and with IV contrast (Fig. 1)) from 6 academic (median reports/site: 23) and 6 community (median reports/site: 17) radiology practices. There were 271 reports describing a possibly malignant mass and 48 reports describing a definitively benign mass.

Possibly malignant masses: essential and preferred elements

Of the possibly malignant masses (N = 271), the majority (87% [N = 236]) were solid without macroscopic fat (Table 1). The remaining 13% were Bosniak IIF (N = 8), Bosniak III (N = 10), and Bosniak IV (N = 17) cystic masses (i.e., stated and inferred, (Table 1)). The distribution of possibly malignant masses was not significantly different between academic and community practices (p = 0.12) (Table 1). Most (95% [N = 257]) were potential nephron-sparing therapy candidates (i.e., T1a or T1b without venous invasion or metastasis).

Some of the elements considered essential to report by academic radiologists and urologists [12] were commonly reported: mass size (99% [269/271]), mass type (solid vs. cystic; 99% [268/271]), enhancement (present vs. absent; 92% [248/271]), and lymph node status (94% [255/271]) (Table 2). However, others were not. Only 14% (34/236) reported the presence or absence of fat for solid masses, 54% (19/35) reported the Bosniak classification for Bosniak IIF-IV cystic masses, 79% (111/140) used available size comparisons, and 51% (137/271) stated the presence or absence of tumor thrombus (Table 2). The only elements reported ≥ 94% of the time were mass size, mass type, and whether lymph nodes were normal or abnormal (Table 2).

Preferred but non-essential elements [12] in general were included in less than half of reports (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5). Features specific to local therapy candidates (e.g., axial and capsular location, position relative to the polar lines) were reported 12-49% of the time (Table 2), and features preferred by urologists (not radiologists) were reported 0-39% of the time (Tables 2, 3, 4, 6). Nephrometry scoring was uncommon (12% [30/257]). When tumor thrombus was reported (N = 18), measurements often were omitted (50% [9/18]); the only measurement commonly reported was distance from the tumor thrombus in the renal vein to the inferior vena cava (50% [9/18]) (Table 3). TNM staging was included in 7% (18/271) of reports.

Academic practices were significantly more likely than community practices to use available size comparisons (p < 0.0001), to report whether lymph nodes were normal or abnormal (p = 0.001), and to report the presence or absence of tumor thrombus (p < 0.0001) (Table 2).

Possibly malignant masses: reporting details

Most academic reports used some form of structure in the report body (87% [142/160]), while most community practices used a free-text narrative style (83% [92/111]) (Table 4). Overall, few reports (6% [18/271]) included a renal mass-specific structured report template (Table 4). There were heterogeneous methods of reporting mass size (Table 4); no method was used in the majority of reports. The most common minority (44% [118/271]) was a tri-planar measurement. The magnitude (79% [213/271]) and presence (57% [155/271]) of enhancement usually were reported in a binary fashion (presence vs. absence) (Table 4).

Academic practices were significantly more likely than community practices to use organ-based or renal mass-specific structured reporting (p < 0.0001), to report mass size with bi-directional or tri-planar measurements rather than with a single diameter (p = 0.007), and to specify whether a portion or all of a mass enhances (p = 0.001) (Table 4).

In the 23 reports that described a possibly abnormal lymph node, lymph nodes usually were measured (87% [20/23]) rather than reported qualitatively (Table 4), and measurements generally were performed in either the short axis alone (48% [N = 11]) or in the short and long axis combined (39% [N = 9]) (Table 4).

Possibly malignant masses: reporting details in the report impression

Reports commonly (70% [189/271]) described the probability that a mass was malignant (Table 5); of those that did, almost all (99% [188/189]) did so qualitatively (e.g., “likely renal cell carcinoma”) rather than quantitatively (Table 4). Reports usually included a differential diagnosis (84% [228/271]) (Table 5). It was uncommon for reports to suggest a particular subtype of renal cell carcinoma (20% [53/271]) or to describe features predictive of favorable histology (10% [24/271]) (Table 5).

Management options were uncommonly offered (18% [49/271]) (Table 5). When given, management recommendations usually included prescriptive language (12% [32/271]; e.g., “should,” “recommend,” “is advised”) rather than optional language (5% [14/271]; e.g., “may,” “consider,” “option[-al]”) or suggestive language (1% [3/271]; “suggest[-ed]”). The most common recommendations were provisions for the type of follow-up imaging to be used (8% [22/271]) and the specific length of the follow-up imaging interval (5% [14/271]). Two reports (0.7%) specifically recommended a treatment strategy (excisional biopsy [N = 1], operative resection [N = 1]). Percutaneous biopsy was mentioned in 2% (5/271) of reports (4 used prescriptive language, 1 used optional language) (Table 5).

Academic practices were significantly more likely than community practices to estimate the probability of malignancy within a mass (p = 0.0002) and to suggest a histologic subtype of renal cell carcinoma (p < 0.0001) (Table 5). Community practices were significantly more likely than academic practices to offer management options (p < 0.0001) and to do so using prescriptive language (p < 0.0001) (Table 5).

Methods of reporting definitively benign masses

Of the 48 definitively benign masses (N = 48), the majority (58% [N = 28]) were Bosniak II benign complicated cysts (Table 1). The remaining 42% (N = 20) were Bosniak I simple cysts (N = 10), classic-type angiomyolipomas (N = 8), renal abscess (N = 1), and renal hematoma (N = 1) (Table 1).

The Bosniak classification system was not used for the majority (66% [25/38]) of benign cystic masses (Table 6). A variety of alternative terms were used instead (Table 6). For example, simple cysts sometimes were referred to as “cysts” without other clarifying terminology, or were provided descriptive terms such as “hypodense lesions” without evident enhancement (Table 6). Bosniak II benign complicated cysts often were reported using variants of “hemorrhagic cyst” or “proteinaceous cyst” (Table 6).

Most (75% [6/8]) reports that diagnosed a classic angiomyolipoma stated the presence of fat; a minority (25% [N = 2]) did not.

Discussion

Renal mass reporting elements considered essential or preferred [12] often are omitted in radiology reports. This is potentially problematic because incorrectly or incompletely characterized renal masses can expose patients to unneeded surgical risk and result in suboptimal clinical decision-making. The only elements reported ≥ 94% of the time in our sample (and therefore statistically likely to be present at least 90% of the time) were mass size, mass type (cystic vs. solid), and whether lymph nodes were normal or abnormal. Preferred but non-essential elements generally were included in less than half of reports. No element preferred solely by urologists was reported more than 39% of the time. Variation exists across radiologists and practice settings despite similar prevalence of mass types. Academic practices were significantly more likely than community practices to include mass characterization details (e.g., size comparisons), a probability of malignancy, and staging details (e.g., lymph node involvement). Community practices were significantly more likely to include management recommendations and to do so using prescriptive language. These differences likely reflect different preferences and pressures upon the radiologists and referring providers attached to those practices.

Underreporting of essential and preferred elements is likely multifactorial: (1) omission of details not observed (e.g., not including mention of macroscopic fat when none is observed), (2) pressure on the radiologist to keep reports short and focused, (3) misunderstanding by the radiologist regarding the clinical relevance of certain elements (i.e., fallaciously assuming that certain elements are necessary or not), (4) differing opinions about the purpose of the radiology report (e.g., as a triage tool to direct care to a urologist vs. as a comprehensive document serving all stakeholders), (5) conflict between idealism stated in a survey and the reality of everyday practice (i.e., reporting elements considered essential or preferred by respondents in a survey may be overly optimistic), (6) differences in reporting patterns and referring provider expectations across sites and settings. Each of these issues likely contributed to our results. Recognizing and addressing sources of variation is potentially important because omission of important details can shift responsibility of image interpretation to the ordering provider and diminish the utility of the radiologist.

To our knowledge, the analysis we conducted has not previously been performed. However, other studies [23,24,25] have shown that variation in radiologist reporting akin to what we observed can be reduced through application of a disease-focused structured report. Such structure is probably best designed through multi-disciplinary consensus [26] to reflect each stakeholder’s viewpoint, achieve face validity, and gain buy-in. Although the use of structured reporting is becoming more popular (87% of academic reports we analyzed had some form of structure), most structured reports are organ-based and do not prompt the radiologist to provide disease-specific information that would be helpful in managing a specific imaging finding. Such disease-specific structured reports [26] are probably the only practical way that relevant detailed information will be included consistently in a radiology report. Variation in reporting between academic and community practices may reflect differences in referring provider expectations and differences in demands on radiologists in those settings. Community radiologists tend to read a higher volume of examinations, are more generalist in their scope of practice, and serve a more diffuse pool of referrers. However, “academic” and “community” distinctions are somewhat arbitrary, as many academic practices (and branches therein) function like community practices, and vice versa.

Our study has limitations. Although we included reports from 6 academic and 6 community practices in the United States, it is possible that our findings might have been different if we had included reports generated outside the United States or by other practices. However, based on the radiology reporting literature in other diseases [23,24,25], it is likely that the variation we observed would be present within and across those practices also. The two organizations we leveraged to obtain the reports—the Society of Abdominal Radiology and the Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative—have a vested interest in quality of care as it pertains to urological conditions. Therefore, it is possible that the comprehensiveness of the reports we analyzed may have been higher than what would be observed in other practices. The majority (87% [N = 236]) of possibly malignant masses we analyzed were solid without macroscopic fat. Therefore, our analyses of possibly malignant cystic masses (Bosniak IIF/III/IV) were underpowered.

In conclusion, radiology reports created to evaluate an indeterminate renal mass often omit elements considered essential or preferred by radiologists and urologists. Significant practice variation exists across community and academic settings. A disease-specific standardized reporting template that is specific to renal masses (and not simply a listing of organs in the abdomen) is probably needed to mitigate these inconsistencies [26]. Future work might be best directed at striking an optimum balance in such a template between efficiency and comprehensiveness.

Change history

16 May 2018

The original version of this article contained an error in author name. The co-author’s name was published as Ivan M. Pedrosa, instead it should be Ivan Pedrosa. The original article has been corrected.

References

Hollingsworth JM, Miller DC, Daignault S, et al. (2006) Rising incidence of small renal masses: a need to reassess treatment effect. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:1331–1334

Lipworth L, Tarone RE, McLaughlin JK (2006) The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 176:2353–2358

Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, et al. (2011) The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 60:615–621

Bjorge T, Tretli S, Engeland A (2004) Relation of height and body mass index to renal cell carcinoma in two million Norwegian men and women. Am J Epidemiol 160:1168–1176

Silverman SG, Israel GM, Herts BR, et al. (2008) Management of the incidental renal mass. Radiology 249:16–31

Herts BR, Silverman SG, Hindman NM, et al. (2017) Management of the incidental renal mass on CT: a white paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2017.04.028

Israel GM, Bosniak MA (2005) How I do it: evaluating renal masses. Radiology 236:441–450

Bosniak MA (2011) The Bosniak renal cyst classification: 25 years later. Radiology 262:781–785

Silverman SG, Israel GM (2015) Trinh, Qouc-Dien. Incompletely characterized incidental renal masses: emerging data support conservative management. Radiology 275:28–42

Society of Abdominal Radiology Disease-Focused Panel on Renal Cell Carcinoma. CT renal mass protocols v.1.0. https://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.abdominalradiology.org/resource/resmgr/education_dfp/RCC/RCC.CTprotocolsfinal-7-15-17.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2018

Society of Abdominal Radiology Disease-Focused Panel on Renal Cell Carcinoma. MR renal mass protocols v.1.0. https://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.abdominalradiology.org//resource/resmgr/education_dfp/RCC/RCC.MRIprotocolfinal-7-15-17.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2018

Davenport MS, Hu EM, Smith AD, et al. (2017) Reporting standards for the imaging-based diagnosis of renal masses on CT and MRI: a national survey of academic abdominal radiologists and urologists. Abdom Radiol 42:1229–1240

Hindman N, Ngo L, Genega EM, et al. (2012) Angiomyolipoma with minimal fat: can it be differentiated from clear cell renal cell carcinoma by using standard MR techniques? Radiology 265:468–477

Silverman SG, Mortele KJ, Tuncali K, et al. (2007) Hyperattenuating renal masses: etiologies, pathogenesis, and imaging evaluation. RadioGraphics 27:1131–1143

Pedrosa I, Sun MR, Spencer M, et al. (2008) MR imaging of renal masses: correlation with findings at surgery and pathologic analysis. RadioGraphics 28:985–1003

Sun MR, Ngo I, Genega EM, et al. (2009) Renal cell carcinoma: dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging for differentiation of tumor subtypes—correlation with pathologic findings. Radiology 250:793–802

Pedrosa I, Alsop DC, Rofsky NM (2009) Magnetic resonance imaging as a biomarker in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer . https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24237

Canvasser NE, Kay FU, Xi Y, et al. (2007) Diagnostic accuracy of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging to identify clear cell renal cell carcinoma in cT1a renal masses. J Urol 198:780–786

Young JR, Margolis D, Sauk S, et al. (2013) Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: discrimination from other renal cell carcinoma subtypes and oncocytoma at multiphasic multidetector CT. Radiology 267:444–453

Oliva MR, Glickman JN, Zou KH, et al. (2009) Renal cell carcinoma: t1 and t2 signal intensity characteristics of papillary and clear cell types correlated with pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 192:1524–1530

Kutikov A, Uzzo RG (2009) The R.E.N.A.L nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location, and depth. J Urol 182:844–853

Dodelzon K, Mussi TC, Babb JS, et al. (2012) Prediction of growth rate of solid renal masses: utility of MR imaging features—preliminary experience. Radiology 262:884–893

Dickerson E, Davenport MS, Syed F, et al. (2017) Effect of template reporting of brain MRIs for multiple sclerosis on report thoroughness and neurologist-rated quality: results of a prospective quality improvement project. J Am Coll Radiol 14:371–379

Brook OR, Brook A, Vollmer CM, et al. (2015) Structured reporting of multiphasic CT for pancreatic cancer: potential effect on staging and surgical planning. Radiology 274:464–472

Sahni VA, Silveira PC, Sainani NI, Khorasani R (2015) Impact of a structured report template on the quality of MRI reports for rectal cancer staging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 205:584–588

Al-Hawary MM, Francis IR, Chari ST, et al. (2014) Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma radiology reporting template: consensus statement of the Society of Abdominal Radiology and the American Pancreatic Association. Radiology 270:248–260

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was solicited or used for this work.

Conflict of interest

Matthew Davenport: Royalties from Wolters Kluwer. Zhen Wang: Unrelated stockholder in Nextrast Inc. Andrew Smith: Unrelated: president of Radiostics LLC, president of and patents received and pending for Liver Nodularity LLC, president of and patents received and pending for eRadioMetrics LLC, presidents of and patents received and pending for Color Enhanced Detection LLC. Hersh Chandarana: Unrelated hardware and software support from Siemens Healthcare. Atul Shinagare: Unrelated consultant to Arog Pharmaceuticals and research funding with GTx Inc. David Miller: Salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for serving as the director of the Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative (MUSIC). Eric Hu, Andrew Zhang, Stuart Silverman, Ivan Pedrosa, Ankur Doshi, Erick Remer, Sam Kaffenberger declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All study procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Institutional review board approval was obtained and subjects consented to participate in the survey.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: The typo in the co-author name has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, E.M., Zhang, A., Silverman, S.G. et al. Multi-institutional analysis of CT and MRI reports evaluating indeterminate renal masses: comparison to a national survey investigating desired report elements. Abdom Radiol 43, 3493–3502 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-018-1609-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-018-1609-x