Abstract

We present a 15-year-old girl with peritoneal metastases from a solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas, which had been excised 6 years previously. This is the third paediatric case with metastases to be reported and the fourth patient with peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas (SPTP) is considered a rare neoplasm [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], usually involving adolescent and young females [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7], and is particularly rare in children [2, 3, 5, 7]. It is generally regarded as a tumour of low malignant potential with a favourable prognosis [3, 5, 6, 7]. Only two paediatric cases with metastatic disease from SPTP have been reported previously [2, 8] and only three adults with peritoneal carcinomatosis have been reported [6, 7, 8]. We present a unique case where peritoneal metastases were discovered on follow-up CT in a 15-year-old girl who had an SPTP excised 6 years previously.

Case report

A 9-year-old girl presented to a peripheral hospital following minor trauma. At laparotomy, the surgeon discovered a lacerated pancreatic mass and performed total resection of the mass. She was referred to a tertiary hospital 2 months later where a repeat exploratory laparotomy failed to demonstrate macroscopic evidence of residual or metastatic tumour. Histologically, the mass was a solid and papillary tumour of the pancreas. None of the initial imaging was available for review.

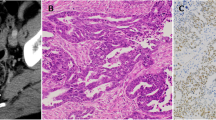

Follow-up imaging for 4 years revealed no recurrence. At 13 years of age, follow-up US and CT demonstrated two 3-cm nodules located in the left renal hilum and left para-aortic region. The surgeon opted to follow the patient with imaging because a good prognosis is expected even in patients with metastatic disease. Repeat CT at 15 years of age, 6 years after initial resection, showed multiple peritoneal and retroperitoneal metastases (Fig. 1). Laparotomy was performed and biopsies were taken of several of the masses. Histology confirmed solid and papillary tumour of the pancreas and a second laparotomy was performed for debulking of the tumour load.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT. a This slice demonstrates lymphadenopathy in the region of the coeliac axis (small arrow) and hypodense lobulated masses in the peritoneal cavity (thick arrow). b A more caudal slice demonstrates numerous peritoneal metastatic deposits (small arrows) and a large metastasis anterior to the left kidney (thick arrow)

Discussion

The incidence of SPTP is unknown [2], probably because of confusion caused by misdiagnosis and misclassification [1, 2, 3, 5]. Only recently has SPTP been recognised as a distinct entity [2, 7], with the number of reported cases increasing from 116 in 1988 to over 450 in 2001 [2]. It now accounts for 3% of all exocrine pancreatic tumours at all ages [2, 3, 5]. The incidence of paediatric SPTP is estimated at 0.01 per 100,000 population [2], with 20–30% of SPTP affecting children overall [2, 8]. Two reviews have calculated no more than 90 reported cases of SPTP in patients less than 18 years of age [2, 3].

The currently accepted official name is 'solid pseudopapillary tumour' of the pancreas, but many terms have been used, including papillary epithelial, papillary cystic, acinar cell tumour, and Frantz tumour [1, 2, 3].

The most common presentation is with a painless abdominal mass [2, 4, 6, 7] (approximately two-thirds of patients [2, 4]), but patients may present with pain and discomfort [2, 4], jaundice, ascites and haemoperitoneum [2, 4]. These masses are slow growing, may remain asymptomatic until they are very large [4] and are discovered incidentally on imaging [4]. Radiological studies in the evaluation of these tumours are essential to define the origin of the mass [6] and assess the liver and peritoneum. CT typically demonstrates a large [3] (mean diameter 9–11 cm [1]), well-circumscribed mass in the pancreas [2, 3], demarcated by a pseudocapsule [3]. The mass can occur anywhere within the pancreas [2], usually has both solid and cystic components [2, 4] and occasionally shows calcification [2]. The imaging features of metastatic lesions have not been described in detail for comparison with our patient. The metastatic foci in our patient were homogeneously isodense to muscle, showed no cystic components and did not enhance significantly.

Most primary pancreatic tumours in children are benign, but the differential diagnosis of a cystic/solid pancreatic lesion in a child should include a pseudocyst, pancreatoblastoma, non-functioning islet cell tumour, SPTP [2, 5, 7], and metastases such as neuroblastoma, leukaemia and lymphoma [3].

Histological assessment of SPTP reveals solid and cystic zones with numerous blood vessels [4]. The solid areas show pseudopapillary or pseudoglandular arrangements of tumour cells [7]. Even though the histological features suggest malignancy and local aggression is noted, the prognosis is good [5]. Metastatic disease is rare [5, 6], with local recurrence being more likely. The incidence of recurrence, local invasion or metastatic disease has been calculated to range between 10 and 15% [1, 3, 4, 8]. Of the 452 cases referred to by Lam et al. [1] and Rebhandl et al. [3], only 66 showed recurrence, local invasion or distant metastases. Metastatic spread has been reported in the liver, lung, skin, peritoneum, omentum and lymph nodes [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Only two reports of children with metastatic disease were found in our literature search [2, 8]. Eleven other children were reported to have local invasion, and a further three cases were reported to have developed recurrence or metastatic disease in later life [8]. Peritoneal carcinomatosis has been reported in only three adults with SPTP [6, 7, 8]. A single case of a child with SPTP, lymphadenopathy and an omental metastasis has been reported [6]. Our patient had numerous peritoneal and retroperitoneal metastases (Fig. 1), which were shown on CT and proved histologically.

Metastatic disease and recurrence are associated with incomplete resection and increasing patient age [7], but our case suggests that trauma may have been the cause of peritoneal and retroperitoneal dissemination. The biological activity of SPTP appears to progress with ageing of the tumour cells [6, 7]. A good prognosis is expected after surgical resection, even in the presence of metastases [8]. It is for this reason that surgery was not performed when the metastatic foci were initially identified in our patient. Tumour-related deaths are uncommon in SPTP [5] and only five patients with metastases (all over 36 years of age) have died from this disease [8]. Most authors recommend wide resection and report good results [2, 3, 4, 8]. It has been suggested that because of the low incidence of metastatic disease in children and the good overall prognosis, the surgical strategy should differ from adults and should be less radical [2]. Our patient represents a dilemma in this regard, as she has presented with extensive distant metastases in childhood after complete resection.

In conclusion, this is a unique case where an SPTP in a child has progressed to peritoneal metastases (probably as a result of trauma) after complete excision. Recurrent disease and metastases in children with SPTP demonstrate that it does not always behave in a 'benign' manner. This diagnosis should be considered when an asymptomatic pancreatic mass is identified in a child, and follow-up with CT is essential after surgical resection to detect recurrence or metastatic disease.

References

Lam KY, Lo CY, Fan ST (1999) Pancreatic solid cystic papillary tumour: clinicopathologic features in eight patients from Hong Kong and review of the literature. World J Surg 23:1045–1050

Zhou H, Cheng W, Lam KY, et al (2001) Solid cystic papillary tumour of the pancreas in children. Pediatr Surg Int 17:614–620

Rebhandl W, Felberbauer FX, Puig S, et al (2001) Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (Frantz tumor) in children: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol 76:289–296

Sclafani LM, Reuter VE, Coit DG, et al (1991) The malignant nature of papillary and cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Cancer 68:153–158

Jung SE, Kim DY, Park KW, et al (1999) Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas in children. World J Surg 23:233–236

Hernandez Maldonado JJ, Rodriguez Bigas MA, Gonzalez De Pesante A, et al (1989) Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. A report of a case presenting with carcinomatosis. Am Surg 55:552–559

Matsunou H, Konishi F (1989) Papillary cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Cancer 65:283–291

Horisawa M, Niinomi N, Sato T, et al (1995) Frantz's tumour (solid and cystic tumor of the pancreas) with liver metastasis: successful treatment and long term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg 30:724–726

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andronikou, S., Moon, A. & Ussher, R. Peritoneal metastatic disease in a child after excision of a solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas: a unique case. Ped Radiol 33, 269–271 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-003-0875-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-003-0875-z