Abstract

Rationale

Neurobiological models of addiction suggest that abnormalities of brain reward circuitry distort salience attribution and inhibitory control processes, which in turn contribute to high relapse rates.

Objectives

The aim of this study is to determine whether impairments of salience attribution and inhibitory control predict relapse in a pharmacologically unaided attempt at smoking cessation.

Methods

One hundred forty one smokers were assessed on indices of nicotine consumption/dependence (e.g. The Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence, cigarettes per day, salivary cotinine) and three trait impulsivity measures. After overnight abstinence, they completed experimental tests of cue reactivity, attentional bias to smoking cues, response to financial reward, motor impulsiveness and response inhibition (antisaccades). They then started a quit attempt with follow-up after 7 days, 1 month and 3 months; abstinence was verified via salivary cotinine levels ≤20 ng/ml.

Results

Relapse rates at each point were 52.5%, 64% and 76.3%. The strongest predictor was pre-cessation salivary cotinine; other smoking/dependence indices did not explain additional outcome variance and neither did trait impulsivity. All experimental indices except responsivity to financial reward significantly predicted a 1-week outcome. Salivary cotinine, attentional bias to smoking cues and antisaccade errors explained unique as well as shared variance. At 1 and 3 months, salivary cotinine, motor impulsiveness and cue reactivity were all individually predictive; the effects of salivary cotinine and motor impulsiveness were additive.

Conclusions

These data provide some support for the involvement of abnormal cognitive and motivational processes in sustaining smoking dependence and suggest that they might be a focus of interventions, especially in the early stages of cessation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

More than 95% of smoking cessation efforts fail within a year (Hughes et al. 2004) despite an armoury of cessation aids and support systems, and there is thus a compelling need to identify individual relapse risk factors in order to refine and target treatments. Contemporary neurobiological models of addiction highlight abnormalities in the mesocorticolimbic ‘reward’ pathways which are activated by addictive substances (e.g. Koob and Nestler 1997) but are hypoactive in abstinent drug users (e.g. Altmann et al. 1996; Volkow et al. 2004). Disturbances of the cognitive and behavioural processes mediated by these pathways, including attribution of salience to external stimuli and inhibitory control over behaviour, may contribute both to the development of dependence and to relapse.

Salience attribution, attentional and motivational responses to incentive stimuli

Goldstein and Volkow (2002) define salience attribution as “analysis of the information that carries emotive, evaluative and, in the long-term, survival significance for the individual”. A stimulus thus tagged with motivational significance elicits affective responses, corresponding approach or avoidance behaviours, and/or attentional biases. The orbitofrontal cortex is strongly implicated as a key brain region involved in salience attribution and is an important element of the interacting mesolimbic and mesocortical dopamine circuits collectively known as the brain reward system (e.g. Rose et al. 2007). This system is activated during drug craving and shows structural and functional abnormalities in current and former users of many addictive substances including nicotine (e.g. Adinoff 2004; Rose et al. 2007). Volkow et al. (2009) argue that addicts' reward systems are hyporeactive and thus respond weakly to non-drug reinforcers, but, through a history of associative learning, respond disproportionately strongly to cues paired repeatedly with drug use. This abnormal state will be most apparent when the individual has abstained from drug intake for at least a few hours so that the effects of the drug are no longer artificially increasing dopaminergic ‘tone’. The consequent imbalance between responsiveness to ‘normal’ and drug-related rewards may contribute to their difficulties in achieving and maintaining abstinence.

There is plentiful evidence that users of addictive substances including alcohol, nicotine and other drugs do show attentional biases to drug-related cues (e.g. Weinstein and Cox 2006) and respond to them with both increases in craving (e.g. Carter and Tiffany 1999) and activation of mesocorticolimbic pathways and/or frontal cortex (e.g. Lingford-Hughes 2005). Heightened awareness of cigarette availability coupled with powerful craving, if experienced early in cessation, is likely to undermine attempts at abstinence; indeed, laboratory indices of attentional bias have predicted relapse in some studies (Waters et al. 2003a; Marissen et al. 2006) though not all (e.g. Waters et al. 2003b). Likewise, stronger physiological or subjective responsiveness to smoking-related cues has sometimes predicted relapse or higher levels of consumption (e.g. Payne et al. 2006) but sometimes not (e.g. Niaura et al. 1999).

If drug users' mesocorticolimbic pathways are indeed hyporeactive, except when artificially stimulated by recent drug ingestion, they should, biologically, be less responsive to drug-related cues when deprived or acutely abstinent; however, the deprivation state may simultaneously elicit an expectancy-driven counter-directional effect in which the experience of withdrawal symptoms inflates the drug's incentive value because of its capacity to give instant relief. There is an extensive literature demonstrating that expectancies do indeed modulate both subjective craving (e.g. Droungas et al. 1995) and neural reactions to drug-related cues (e.g. McBride et al. 2006). Depending on the relative strength of these opposing effects, attentional bias and cue-elicited craving could increase, decrease or be unchanged during abstinence. In fact, the few studies which have compared smokers' responses in abstinent versus satiated states have not found strong or consistent differences between them either for attentional bias (e.g. Field et al. 2004; Mogg and Bradley 2002) or cue reactivity (e.g. Waters et al. 2004; Alsene et al. 2005). It may well be that the effects of acute abstinence vary between individuals because of differences in factors affecting either their biological or psychological responses (e.g. severity of dependence and personality traits). Regardless of what the determinants are, we hypothesize here that those smokers who experience the most pronounced attentional biases and cue reactivity during the early stages of a cessation attempt will be at heightened risk of early relapse.

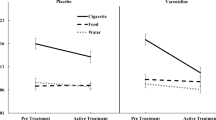

Assuming that drug ingestion acutely increases the overall reactivity of reward pathways in dependent drug users, it should enhance their biological responsiveness to all types of motivationally salient stimuli and not just to those which are drug related. By contrast, there is unlikely to be an opposing cognitive effect of abstinence on responses to non-drug stimuli since in general they will not be perceived as offering relief from withdrawal symptoms. Consequently, our group has previously hypothesized that acute (10–12 h) abstinence from smoking should be associated with a straightforward reduction in smokers' reactivity to non-drug stimuli compared to their reactivity after consuming nicotine via cigarette or lozenge. We have found abstinence to be associated with diminished behavioural responses to financial incentive (Al-Adawi and Powell 1997; Powell et al. 2002a, b; Dawkins et al. 2006), reduced anticipation of enjoying everyday pleasures (Powell et al. 2002a), less attentional bias towards pleasure-related words (Powell et al. 2002b; Dawkins et al. 2006) and decreased mood ‘uplift’ in response to positively toned film clips (Dawkins et al. 2007b). Similarly, Cook et al. (2007) reported that nicotine-facilitated positive mood induction in anhedonic smokers. There are however some studies which have not found such effects (e.g. Kalamboka et al. 2009), possibly reflecting differences in study designs, assessment procedures or sample characteristics. For example, smokers are likely to vary in the extent to which abstinence depresses their appetitive responses, perhaps as a function of pre-existing differences in personality and brain function or variations in smoking history. In any event, if some smokers do experience a loss of interest in non-drug rewards and pleasures (anhedonia) during early cessation and are able to reverse this by smoking, then they are likely to be at an elevated risk of relapse (e.g. Leventhal et al. 2008).

Response inhibition/inhibitory control

Increasing evidence of deficient inhibitory control (i.e. ability to suppress automatic but inappropriate responses) in drug users may likewise reflect dysregulation of frontostriatal brain regions (Volkow et al. 2008; Jentsch and Taylor 1999; Yucel and Lubman 2007). Relative to non-smokers, smokers have been found to be impaired on behavioural indices of impulse control in oculomotor (antisaccade), go/no-go and delayed alternation tasks (e.g. Spinella 2002), to take more risks in decision making (Lejuez et al. 2003) and to show abnormally strong preferences for immediate or certain rewards over larger but delayed or less certain rewards (delay or probability discounting, e.g. Bickel et al. 1999; Mitchell 1999; Reynolds et al. 2004). These deficits, as with salience attribution, may be most evident in smokers during acute abstinence; thus, smokers have shown lower antisaccade accuracy—indicating poorer inhibitory control—after 12 h of abstinence than after smoking (Powell et al. 2002a) or consuming a nicotine lozenge (Dawkins et al. 2007a) whilst Field et al. (2006) found their delay discounting of nicotine and monetary rewards to be more pronounced during acute abstinence than after ad libitum smoking. If these inhibitory control impairments affect the ability to restrain habitual real-world behaviours, then they will contribute to the difficulty smokers experience in resisting the urge to accept or reach out for a cigarette, especially during the early stages of a cessation attempt.

Impulsivity is a complex personality trait often considered the behavioural phenotype of consistently weak inhibitory control. Varying theoretical conceptualizations of the trait have given rise to impulsivity measures which intercorrelate only moderately or which fractionate into partially independent factors (e.g. Meda et al. 2009; Dawe et al. 2004). Nevertheless, smokers generally score relatively highly on such scales (e.g. Lejuez et al. 2003; Mitchell 1999). Whilst Doran et al. (2004) found one widely used measure of trait impulsivity to predict speed of relapse in adult smokers, Krishnan-Sarin et al. (2007) found no such relationship in adolescents; interestingly, however, in this group relapse was predicted by two behavioural indices of impulsiveness (delay discounting and commission errors on a Continuous Performance Task). There has been little other research directly investigating the relationship between impulsivity and relapse, and thus several tasks and trait measures have been employed here to provide at least a preliminary indication of whether some facets of the construct have more utility than others in predicting the ability to quit smoking.

The present study

This study explores the extent to which several indices of salience attribution and inhibitory control, measured immediately prior to an unassisted smoking cessation attempt, account for separate or overlapping variance in time to relapse. Inter-relationships with other known prognostic factors, in particular physical and psychological dependence, are also of interest given that relapse risk is positively associated with self-report dependence measures (Piper et al. 2008), number of cigarettes per day (Myung et al. 2007) and level of craving during early abstinence (al’Absi et al. 2004). Correlations with biological markers of nicotine consumption such as salivary cotinine have also been reported (Nørregaard et al. 1993).

Different indices of dependence and smoking behaviour intercorrelate with each other; for instance, Rubinstein et al. (2007) found high correlations between various self-report measures and salivary cotinine. This could reflect shared associations with mesocorticolimbic functioning. Specifically, heavier nicotine intake may lead to greater neuroadaptation in mesocorticolimbic pathways, exacerbating motivational disturbances and anhedonia; and these aversive states may increase the individual's self-reported dependence on smoking to enhance subjective well-being. Despite evidence that indices of dependence and consumption correlate with one another, they have been found to be at least partially independent in moderate to heavy smokers (Donny et al. 2008); consequently, several measures were included here.

In addition to measuring the individual contributions of all these factors to relapse, logistic regression was used to investigate whether the behavioural indices of salience attribution and inhibitory control explained unique variance in outcome after controlling for level of dependence.

Methods

Study design

This prospective investigation of relapse predictors was part of a larger project (Dawkins et al. 2006; 2007a; 2009) in which 141 smokers were assessed after overnight abstinence on two occasions a week apart, prior to commencement of an unaided quit attempt. Immediately before each assessment, they consumed lozenges containing 4 mg or 0 mg of nicotine (order counterbalanced; double-blind). They were then tested on experimental measures of cue-elicited craving, salience attribution and response inhibition. Scores in the placebo (0 mg) condition are indicative of the disturbances each individual smoker is likely to experience during early abstinence and are the indices of interest in the present study. There was no effect of session order (i.e. whether participants had been tested in the placebo condition on the first or second occasion) on any of the indices reported upon here.

Participants started their quit attempt immediately after the second assessment. They were instructed not to use nicotine replacement or other medication, but no other forms of assistance were precluded and they were given written information about the symptoms and difficulties they might experience, together with some advice on non-pharmacological coping strategies.

Follow-up assessments were at approximately 7 days, 30 days and 3 months after the quit date. Given that the principal objective of the study was to investigate predictive relationships between quantitative measures of functioning at baseline and success in becoming and remaining nicotine free, it was decided to utilize a rather stringent definition of relapse which could be biologically verified with a reasonable degree of confidence, rather than the more forgiving definitions appropriate for evaluating interventions or the time course of cessation attempts (see, e.g. Hughes et al. 2003). Participants reported on their cigarette consumption since the previous assessment and were classified as relapsers if they admitted to more than two cigarettes in any single week. All those who did not were required to give a saliva sample for cotinine testing, and those with levels higher than 20 ng/ml were also classified as relapsers. Non-smokers have levels up to 13 ng/ml, each cigarette per day being associated with approximately an additional 14 ng/ml (Etter et al. 2000), and after 7 days of continuous abstinence smokers' levels are generally comparable with those of non-smokers (Abrams et al. 1987). Thus, the present cut-off is consistent with only minimal recent smoking. These data thus assess the point prevalence of near-complete abstinence over the preceding 7 days, an index which has been shown to correlate highly with indices of continuous and prolonged abstinence (Velicer and Prochaska 2004). In rare instances where salivary samples were missing, the participant was excluded from the analysis of outcome at that follow-up point. Once a participant was deemed to have relapsed, his/her classification was not subsequently reversed even if he/she reported resumption of full abstinence.

On each consecutive occasion, participants who remained abstinent were reassessed in order to investigate recovery of function (Dawkins et al. 2009). There was a modest financial incentive to remain abstinent in that payments for consecutive assessments (which ceased following relapse) increased in size and were accumulated and paid only at the final meeting with the participant. This helped to motivate attendance at follow-ups. Thus, participants who relapsed before the first follow-up earned only £40 (for attending baseline and one follow-up assessment) whilst those abstaining throughout and completing all three follow-up assessments received £150.

The study was approved by Goldsmiths Ethics Committee, and participants gave their informed consent. In relation to the ethics of allocating smokers to an explicit ‘continue smoking’ condition, it should be noted that smokers were recruited from the community rather than from settings such as smoking clinics where their presence would have indicated an immediate intention or action plan to quit. Individuals with specific health problems contraindicating smoking were excluded, and participants allocated to the ‘continue smoking’ condition were free to withdraw from the study in order to try and quit or cut down at any point whilst still receiving payment for their participation until that point. Likewise, participants allocated to the quit condition, which precluded use of nicotine replacement or other drug treatments, were free to withdraw from the study in order to use such aids whilst still being paid for their time and effort until that point.

Participants

Recruitment was via advertisements in the local community, a relatively deprived urban area in South London. Eligibility criteria were age 18–65, having smoked 10+ cigarettes per day over the preceding year; smoking within the first hour of waking; being willing to make an unaided quit attempt whether or not they were currently planning to do so and being willing to continue smoking for the 3-month duration of the study if randomized to that condition. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, serious heart disease, recent stroke, prescribed psychoactive medication (e.g. antidepressants), regular use of UK “Class A” illicit recreational drugs (including heroin, cocaine, ecstasy, LSD, amphetamines) and pre-cessation salivary cotinine levels below 40 ng/ml.

Assessment measures

Small amounts of data were missing for some variables as shown in Table 1.

Baseline (pre-cessation)

Indices of smoking severity/dependence

-

Cigarettes smoked per day on average over the past year (self-report)

-

Salivary cotinine. Cotinine concentrations in saliva samples were analyzed by gas chromatography.

-

The Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al. 1991 ). Scores on this self-report scale range from 0 to 10 (low to high dependence).

-

Dependence scale from the Smoking Motivation Questionnaire (SMQ; West and Russell 1985). Total scores range between 0 and 27 (high dependence).

Trait impulsivity was assessed via subscale scores from three well-validated personality questionnaires tapping different but related facets of the construct:

-

The Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS; Zuckerman et al. 1978): Excitement seeking, boredom susceptibility, thrill and adventure seeking and disinhibition subscales plus the total score.

-

The Novelty Seeking subscale of the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ-NS; Cloninger 1987)

-

The Impulsivity subscale from the Impulsivity, Venturesomeness and Empathy questionnaire (IVE-Imp, Eysenck and Eysenck 1991).

Clinical and experimental indices assessed after 12 h of abstinence

Full details are given in Dawkins et al. (2006, 2007a). At the start of the session participants rated:

-

Craving at that moment via the single item ‘How strong is your desire to smoke right now’; 1 = not at all strong; 7 = extremely strong. Whilst craving is undoubtedly a complex construct (see, e.g. Shadel et al. 2001; Shiffman et al. 2004), single-item indices such as this have been found to be as sensitive and reliable as multi-item measures (West and Ussher 2010) and have the practical benefits of simplicity and brevity.

-

Withdrawal symptoms at that moment, via the Mood and Physical Symptoms Scale (MPSS; West and Hajek 2004); score range, 0–28 (severe).

-

Mood over preceding week via the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond and Snaith 1983). Anxiety and Depression scores range from 0 to 21.

Subsequent experimental measures comprised:

Indices of salience attribution

-

Attentional bias to smoking-related cues. This was assessed via a modified Stroop test (see Powell et al. 2002a, b, for full details). Participants colour-named the ink in which each of 88 words was printed on a single sheet of paper. Four conditions, in counterbalanced order, utilized words of different types: neutral, appetitive, aversive and smoking related. The construct of theoretical interest was attentional bias towards smoking-related stimuli (SmokeBias), indexed by subtracting colour-naming errors for neutral words (e.g. pavement, cadet) from those for smoking-related words (e.g. cigarette, lighter). We focused on errors rather than speed given our previous finding (Dawkins et al. 2006) that acute abstinence affected the former but not the latter.

-

Cue reactivity: Craving elicited by smoking-related cues. Participants rated their craving and withdrawal symptoms (as above) twice, following 2-min exposures firstly to a neutral cue (scotch tape) and secondly to a cigarette of their preferred brand; in both cases they took the cue from a box and smelled it. Cue reactivity was the difference between the two ratings (smoking cue–neutral cue). Presentation order was fixed so that the derived index was based on identical procedures for all participants.

-

Responsiveness to non-drug incentives. This was assessed via the Card Arranging Reward Responsivity Objective Test (CARROT; Al-Adawi and Powell 1997), which indexes the performance–enhancing effect of financial incentive. Participants sorted cards according to a simple explicit rule under conditions of reward (R) and no reward (twice: NR1 and NR2) in the order NR1, R, NR2. The card-sorting rate (cards/second) in condition R relative to the average rate in NR1 and NR2 is the ‘reward responsivity’ index. Again, the fixed presentation order means that this index is comparable across participants.

Indices of inhibitory control

-

Oculomotor response inhibition. Fukushima et al.'s (1994) antisaccade task was employed. Participants were instructed to look either towards or away from a peripheral stimulus as quickly as possible after it flashed up on a computer screen. Eye movements (saccades) were recorded using an infrared reflection technique (IRIS IR 6500 by Scalar Medical). A first set of 60 stimuli were presented under prosaccade instructions, and after a 5-min interval, a second set of 60 were presented under antisaccade instructions. Any initial movement in the wrong direction constituted an error. The dependent variable used here was percentage errors in the antisaccade condition. This simple index of inhibitory control is impaired during acute abstinence (e.g. Dawkins et al. 2007a). Trials where no eye movement was recorded were excluded, and nine participants for whom data were missing for more than 50% of their trials were excluded from these analyses.

-

Motor impulsiveness. Participants' ability to inhibit maladaptive motor responses was assessed via Dougherty et al.'s (1999) Continuous Performance Task (CPT). Five-digit numbers were presented visually at a rate of 2/s for 5 min. ‘Targets’ (sequences with no obvious structure, e.g. 97528) were separated one from the next by three ‘filler’ stimuli of the fixed form 12345; participants had to press a button when two consecutive targets were identical. ‘Motor impulsiveness’, manifesting as errors of commission to filler stimuli, was elevated in these smokers during acute abstinence (Dawkins et al. 2007a). Data were missing for nine participants.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regressions assessed the predictive relationship of each variable separately to outcome (continuous abstinence vs relapsed with abstinence verified by salivary cotinine) at a week, a month and 3 months. Inter-relationships between predictors were then investigated through a series of hierarchical logistic regressions (HLRs) constructed to address specific questions and to constrain the number of independent variables within each analysis. In the first HLR, the four smoking/dependence measures were entered as predictors; only those which accounted for unique variance in outcome status were retained in subsequent HLRs investigating the joint contributions of individually significant predictors to outcome at each follow-up. Participants with missing data on any variable in a given analysis were excluded from it; hence, sample sizes vary between regressions.

Additional correlational analyses were conducted to test specific hypotheses concerning relationships between smoking/dependence indices and other variables.

Results

Participants

Sixty-five out of 141 (46.1%) were male. One hundred nine (77.3%) described themselves as white, eight (5.7%) as African–Caribbean, ten (7.1%) as Asian, two (1.4%) as Hispanic and 12 (8.5%) as ‘other’.

Most continuous variables were approximately normally distributed. Mean age was 33.2 ± 12.8 years (range, 18–65). Self-reported daily cigarette consumption was 19.4 ± 7.1 (range, 10–40; median, 17) and salivary cotinine at baseline was 285 ± 156 ng/ml (range, 44–940). One hundred thirty seven participants completed the FTND, the mean score being 5.1 ± 1.9 (median, 5; range, 2–10). Number of years smoking was slightly skewed to the left with a mean of 16.8 ± 13.0; the median was 12 years (range, 1–50). This was the first quit attempt for 31 participants with 84 (59.5%) having made from one to three and nine (6.4%) 10+ previous attempts; on average they had made 2.4 ± 2.7 attempts. About half used cannabis occasionally: and mean frequency of use in the last month was 5.6 ± 9.7 days.

At each follow-up all participants who had been abstinent at the previous assessment were reassessed. Cotinine levels for abstainers were mostly below 13 ng/ml (consistent with total abstinence) but slightly higher (13–20 ng/ml, indicative of occasional smoking) for six at a week, two at a month and three at 3 months. Samples were missing for two cases who claimed to be abstinent at one and 3 months, and they were excluded from analyses of outcome on the latter occasions. Thus, numbers were 141 at a week and 139, subsequently. Sixty-seven participants (47.5%) were abstinent at 1 week, 49 (35.2%) at a month and 33 (23.7%) at 3 months.

Relationship of individual variables to outcome

Table 1 gives descriptive data for all variables assessed during acute abstinence at baseline, Table 2 shows their individual associations with outcome at each follow-up and Table 3 shows the hierarchical linear regressions at each assessment point.

Indices of smoking/dependence

Relapse within 7 days was significantly predicted by pre-cessation salivary cotinine (SalCot), FTND score and cigarettes per day; relapse within a month by SalCot and cigarettes per day; and relapse within 3 months only by SalCot. SMQ dependence showed a near-significant association only with a 7-day outcome.

The four indices were significantly intercorrelated: salivary cotinine correlated at 0.44 with the number of cigarettes per day, 0.42 with FTND scores and 0.25 with SMQ dependence; the number of cigarettes per day correlated at 0.68 with the FTND and 0.38 with SMQ dependence; and FTND correlated at 0.45 with SMQ dependence (p < 0.005 in all cases). In an HLR, the four smoking variables collectively explained about 13% of the variance in the 1-week outcome (χ 2 = 13.3, df = 4, p < 0.01; Nagelkerke pseudo R 2 = 0.13). SalCot was the strongest predictor (χ 2 = 5.2, p < 0.03); all the others could be removed from the model without significant deterioration in fit (χ 2 < 1, in each case). This was likewise true at 1 and 3 months.

Prediction of abstinence at 1 week

Outcome at a week was unrelated to age, gender, trait impulsivity measures and all clinical symptoms (mood, withdrawal symptoms, craving) measured during acute abstinence. By contrast, it was significantly associated with scores on most of the experimental indices of motivational and inhibitory control in the acute abstinence baseline assessment, thus relapse was predicted by higher levels of cue reactivity and attentional bias towards smoking-related cues and by weaker response inhibition as indicated by antisaccade errors and motor impulsiveness on the CPT. These variables were uncorrelated with each other (r < 0.10, ns, for all pairs of variables). Reward responsivity on the CARROT was the only experimental index not to predict outcome.

The relationship of outcome to attentional bias was specific to smoking-related stimuli rather than reflecting a general tendency for attention to be captured by motivationally significant stimuli. Thus, outcome did not correlate with attentional bias towards either threat-related or pleasure-related words (indexed by subtracting error scores in these conditions from that in the neutral condition; χ 2 = 2.9 and 0.4, ns, respectively).

HLR investigated the combined explanatory power of all the individually significant predictors, including SalCot. Complete data were available for 124 participants, of whom 57 (46%) were abstainers and 67 (54%) relapsers. Non-significant predictors were then removed in a hierarchical series of regressions. The final model retained SalCot, attentional bias and antisaccade errors. Collectively, these provided a significantly better fit to the data than an intercept-only model (χ 2 = 22.2, df = 3, p < 0.001), explaining about 20% of the variance as indicated by a Nagelkerke pseudo R 2 estimate of 0.20. Further likelihood ratio tests demonstrated that none of the predictors could be removed without a significant deterioration in fit (χ 2 = 10.1, 5.8 and 4.0 respectively; p < 0.05 in each case). Table 3 shows the odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals, for each of the predictors in the final model. The odds of relapsing relative to remaining abstinent increased by approximately 0.4% for each 1 ng/ml increase in baseline cotinine levels, by about 30% for each additional ‘interference error’ produced by smoking-related words on the Stroop task and by about 1.9% for every additional antisaccade error.

For interest, we additionally computed the relationships of outcome to scores on the same experimental indices assessed when participants were nicotine-satiated at baseline (i.e. after consumed the lozenge containing 4 mg nicotine). In this condition, only antisaccade errors significantly predicted relapse (χ 2 = 5.2, p = 0.023).

Prediction of abstinence at 1 month

Of the demographic, clinical status, personality and experimental variables, only cue reactivity and motor impulsiveness significantly predicted relapse at a month, though there was a similar trend for attentional bias to smoking cues (p < 0.06). These three variables were entered with SalCot into an HLR based on 131 participants (34.4% abstainers, 65.6% relapsers) with complete data. Only SalCot and motor impulsiveness were retained in the final model which fitted the data significantly better than an intercept-only model (χ 2 = 17.10, df = 2, p < 0.001); neither could be removed without significant deterioration in fit (χ 2 = 10.6 and 6.0; p < 0.02 in both cases), and they explained an estimated 17% of the variance (Nagelkerke pseudo R 2 = 0.17). As shown in Table 3, every 1 ng/ml increase in baseline cotinine levels increased the odds of relapse relative to abstinence by approximately 0.4%, and each additional impulsive motor error on the CPT increased the odds by 8%.

Prediction of abstinence at 3 months

Three variables remained individually significantly predictive of outcome at 3 months: SalCot, cue reactivity and motor impulsivity. An HLR based on 130 participants [30 (23.1%) abstainers vs 100 (76.9%) relapsers] eliminated cue reactivity; the final model fitted the data significantly better than an intercept-only model (χ 2 = 13.9, df = 2, p < 0.001) explaining an estimated 15% of the variance (Nagelkerke pseudo R 2 = 0.15), and neither SalCot nor motor impulsiveness could be removed without significant deterioration in fit (χ 2 = 8.9 and 4.6, respectively; p < 0.04 in both cases). Table 3 shows that the odds of relapsing relative to remaining abstinent increased by 0.5% for every 1 ng/ml increase in baseline cotinine levels and by 8.5% for each additional impulsive motor error on the CPT.

Discussion

A handful of previous studies have found cue reactivity, attentional bias to smoking-related cues or indices of inhibitory control assessed experimentally to be predictive of relapse to smoking (e.g. Payne et al. 2006; Marissen et al. 2006; Krishnan-Sarin et al. 2007). The present study, however, is the first to have assessed the predictive relevance of all these variables concurrently in a prospective study controlling for level of dependence.

As anticipated, indices of nicotine consumption and dependence were strong predictors of relapse, reflecting the well-established tendency for heavier smokers to have the greatest difficulty quitting. The finding that pre-cessation cotinine levels predicted relapse more strongly than either subjective ratings of nicotine dependence or the severity of self-reported somatic and affective withdrawal symptoms is consistent with a previous research showing daily cigarette consumption and salivary cotinine to stronger predictors than self-report dependence measures (e.g. Breslau and Johnson 2000; Nollen et al. 2006). These data suggest that underlying biological factors are greater influences on continued smoking than are the associated subjective aspects of dependence.

Whilst salivary cotinine levels were the strongest predictor of outcome, attentional bias towards smoking-related cues and poor inhibitory control over simple motor responses during acute abstinence explained additional unique variance. Strikingly, these experimental indices and also cue reactivity were stronger predictors of relapse within a week than were severity of withdrawal symptoms, craving and low mood during acute abstinence or trait impulsivity.

Analyses of outcome predictors focused on the experimental indices assessed during acute abstinence given that any difficulties experienced in this state are the ones with which smokers have to contend in order to remain abstinent. Theoretically, it is also during early abstinence that underlying abnormalities of brain functioning are likely to be unmasked. These assumptions are consistent with the finding that participants' scores on the same indices after recent nicotine intake (via a 4-mg lozenge) were markedly less predictive of a 7-day outcome than were scores during acute abstinence. Indeed, only one of the indices (antisaccade error rate) predicted relapse when assessed in the satiated condition. Cue reactivity, attentional bias to smoking cues and motor impulsiveness were not predictive by contrast with their predictive effects when assessed during acute abstinence.

The absence of intercorrelations between the four cognitive/motivational predictors of outcome reflects previous published findings (e.g. McDonald et al. 2003) and is difficult to reconcile straightforwardly with the theoretical premise that they are all similarly influenced by abnormalities of functioning in shared mesocorticolimbic brain circuitry. Whilst differences between tasks in terms of non-shared processes, content or procedural details will tend to weaken associations, the lack of evidence for even modest inter-relationships suggests either that the processes putatively tapped by the tasks do not depend on shared neuronal mechanisms or that the tasks are not, after all, sensitive to those processes. At the very least, the present data indicate that attentional bias towards smoking-related stimuli and the craving elicited by them are independent aspects of salience attribution and that antisaccade errors and failure to inhibit manual motor responses in the Continuous Performance Task tap different and unrelated facets of inhibitory control. Dissociations between inhibitory control indices similar to those used here have been reported and discussed by other groups (e.g. Nigg et al. 2002; Chikazoe et al. 2007). The latter group, for example, explored the dissociation between a go/no-go task (similar to the CPT) and antisaccade performance noting that the former, but not the latter, consistently activates the right lateral prefrontal cortex. By experimentally varying task protocols, they found evidence that the relevant distinction is the extent to which a ‘preparatory set’ is instigated prior to stimulus presentation (stronger in the antisaccade than the go/no-go task).

Functional neuroimaging studies may, in time, explain these theoretically unexpected process dissociations. At a practical level, however, it is interesting to consider how and why performance on these laboratory-based tasks is predictive of relapse. Perhaps they simply do “what they say on the tin”, that is, the Stroop index of attentional bias to smoking-related words reflects the extent to which newly abstinent smokers are tuned in to cues of cigarette availability. The experimental cue reactivity index reflects the craving they experience in response to real-world cues of cigarette availability. CPT–motor impulsiveness indexes difficulties in motor control akin to those that smokers have in inhibiting their overlearned behavioural tendency to reach out for a cigarette when it is available, and antisaccade errors reflect difficulties in overriding prepotent responses (such as lighting up) by substituting an alternative and incompatible action; however, whilst this account offers a plausible description of how processes tapped by the individual tasks may jointly conspire to increase the likelihood of relapse, it begs the question of their unexpected lack of covariation. Clearly, this is an issue demanding much further investigation.

The only experimental variable which did not predict relapse at any point was reward responsiveness indexed by the degree to which monetary reward enhanced card-sorting (CARROT) performance. This measure was depressed during acute abstinence in the present sample (Dawkins et al 2006), consistent with down-regulation of their reward system. We conjectured that if abstainers experience this state (apathy) as aversive, they might experience heightened temptation to smoke in order to restore normal hedonic tone or drive state and hence be at an elevated risk of relapse. The present negative findings contradict this hypothesis. It is possible that generalized impairments of motivation might, by contrast, reduce abstainers' likelihood of engaging in planning and actions necessary to smoke when cigarettes are not immediately available; if so, these two opposing effects of apathy could offset one another in terms of overall relapse risk. This would, however, be difficult to verify, and for all practical purposes the conclusion must be that impairment of reward responsiveness per se has little or no relevance to successful abstinence.

None of the three self-report impulsivity measures predicted relapse. Smokers are typically high in trait impulsivity (e.g. Gurpegui et al. 2007; Mitchell 1999), but only two previous studies have investigated its relevance to smoking cessation. Both used the Barratt Impulsivity Scale: Doran et al. (2004) found it to be positively correlated with rapidity of relapse in 45 adult smokers with a history of depression, but Krishnan-Sarin et al. (2007) found no association with 1-month cessation rates in 30 adolescents. The present sample was larger and more representative of adult smokers, and the use of multiple questionnaires enabled the potential impact of several different conceptualizations of impulsivity to be investigated. The contrast between the failure of any of these scales to predict relapse and the predictive significance of several behavioural indices is consistent with other evidences of such dissociations in the context of impulsivity and substance use (e.g. McDonald et al. 2003; Reynolds et al. 2006; Verdejo-Garcia et al. 2008). In particular, Krishnan-Sarin likewise found neurocognitive measures of impulsivity to outperform trait measures in predicting relapse to smoking, as did Goudriaan et al. (2008) in relation to gambling. From a clinical perspective, therefore, these findings suggest that whilst many smokers may have an impulsive personality, cessation-related interventions might most productively focus on abnormalities in objectively measurable cognitive and motivational processes such as those found here to predict relapse.

A general methodological problem for studies such as this, which employ multiple indices of putative underlying processes, is that there is no way of being certain that the indices are comparable in accuracy, sensitivity or reliability. The absence of an expected relationship with relapse might thus reflect inadequate psychometric properties or poor construct validity of the predictor variable; likewise, a stronger relationship with one index than with another could reflect their differing sensitivities rather than a real difference in the importance of the corresponding processes. It would therefore be premature to infer simply from the magnitude of different correlations that motor impulsiveness is more important to relapse than cue reactivity or that reward responsiveness is irrelevant. Future research employing better or different measures may reveal different patterns. Relatedly, procedural factors—often unavoidable—are likely to compromise the sensitivity of some experimental indices. For instance, high levels of craving at baseline may have reduced the scope for cue reactivity in some participants. The emergence of significant associations despite such measurement problems is therefore quite compelling evidence for the relevance of the variables concerned and suggests that the observed effect sizes may be conservative indications of the real importance of these processes.

It is interesting that the unique contributions to relapse risk made by cognitive/motivational processes assessed during acute abstinence were more pronounced in the first week of the cessation attempt whilst the predictive utility of pre-cessation systemic nicotine levels remained fairly constant across all three follow-up points. One possible explanation is that there is more rapid recovery of cognitive and motivational processes tapped by our experimental measures than in some other aspects of functioning so that those smokers who maintain abstinence over the early period are subsequently less affected by their early motivational and cognitive vulnerability. Thus, if some of the biological abnormalities associated with smoking—whether they pre-existed the onset of smoking or were to some extent smoking-induced—are relatively long lasting, they are rather likely to exert a persistent effect on relapse risk. On the other hand, it is possible that recovery in some aspects of brain function precedes others and that the experimental measures employed here are sensitive to those early changes. In this regard, it is pertinent that abstinent alcoholics show substantial cognitive recovery over a matter of weeks or a few months (e.g. Mann et al. 1999) even though they remain at high risk of relapse for much longer. The present sample was unfortunately not of sufficient size for this explanation to be tested so it remains purely speculative. From a purely clinical perspective, however, it is noteworthy that whilst the predictive impact of attentional bias and antisaccade error rate declined from one follow-up to the next, motor impulsiveness and cue reactivity remained predictive of relapse right up to 3 months. The effect of cue reactivity appears to reflect underlying biological factors since it did not explain additional variance over and above that explained by baseline salivary cotinine; however, this does not render it uninteresting—indeed, rather the reverse. Pre-existing biological risk factors such as prior nicotine consumption are not themselves modifiable, but the processes they underpin and which are the proximal drivers of behaviour may well be more susceptible to intervention. Thus, if as suggested by these findings, heightened cue reactivity is in part a reflection of dependence and is one of the important processes by which dependence leads to increased relapse risk, then it makes sense to try either to modify the cue reactivity itself or to equip the individual with strategies to contend with it. Motor impulsiveness was to some extent independent of dependence, explaining additional variance in outcome and is therefore likewise an important candidate for treatment focus in supportive interventions which extend beyond the very early stages of cessation.

Abstinence rates of 47.5% at a week, 35.2% at a month and 23.7% at 3 months are at or above the upper end of the range reported in studies of unassisted cessation; thus, Hughes et al. (2004) report rates at the corresponding intervals of 24–51%, 15–28% and 10–20%. It is likely that the combination of repeated assessments and the participation payment schedule, which withheld payment until the end of the study and gave incrementally greater financial rewards to those who abstained for longer, contributed to this. Monetary incentives appear to boost cessation rates over 3 months (e.g. Lamb et al. 2007) although there is little evidence that they impact positively on long-term abstinence (Cahill and Perera 2008). We did not determine whether participants had used any specific forms of treatment or support during their abstinence attempt, though they were instructed not to use nicotine replacement therapy or other medication. Whilst the present study in any case lacked the statistical power to evaluate possible moderator effects of different treatments on the relationships between predictors and relapse, it is an important issue for future research.

Given that half of all participants had—as elsewhere (e.g. Hughes et al. 2004)—relapsed within the first week, interventions prior to and during the first week of a cessation attempt might valuably focus on the cognitive and motivational variables which significantly predicted early relapse. Clinicians could consider assessing individual smokers on each of these indices prior to their cessation attempt in order to both inform them of their personal risks and to tailor advice and support accordingly. For example, a smoker who performs poorly on an inhibitory control task and shows pronounced attentional bias to smoking cues could be helped to develop strategies to avoid or handle situations where cigarettes are available. Such advice, whilst not in itself innovative and part of many cognitive–behavioural interventions, could take on particular motivational force if the individual has been pre-assessed as having the relevant personal risk factor(s). It is further worth considering in particular whether quitters might specifically be assisted to enhance their inhibitory control via techniques focusing on general alertness—for example, making a conscious effort to regulate sleeping habits, limiting alcohol intake, increasing physical activity, engaging in mentally stimulating activities and possibly even judicious consumption of some caffeinated drinks.

References

Abrams DB, Follick MJ, Biener L, Carey KB, Hitti J (1987) Saliva cotinine as a measure of smoking status in field settings. Am J Public Health 77:846–848

Adinoff B (2004) Neurobiologic processes in drug reward and addiction. Harv Rev Psychiatry 12:305–320

al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL, Wittmers LE (2004) Prospective examination of effects of smoking abstinence on cortisol and withdrawal symptoms as predictors of early smoking relapse. Drug Alcohol Depend 8:267–278

Al-Adawi S, Powell JH (1997) The influence of smoking on reward responsiveness and cognitive functions: a natural experiment. Addiction 92:1757–1766

Alsene KM, Mahler SV, de Wit H (2005) Effects of d-amphetamine and smoking abstinence on cue-induced cigarette craving. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 13:209–218

Altmann J, Everitt BJ, Glautier S, Markou A, Nutt D, Oretti R, Phillips GD, Robbins TW (1996) The biological, social and clinical bases of drug addiction: commentary and debate. Psychopharmacol 125:285–345

Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ (1999) Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacol 146:447–454

Breslau N, Johnson EO (2000) Predicting smoking cessation and major depression in nicotine-dependent smokers. Am J Public Health 90:1122–1127

Cahill K, Perera R (2008) Competitions and incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16:CD004307

Carter BL, Tiffany ST (1999) Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction 94:327–340

Chikazoe J, Konishi S, Asari T, Jimura K, Miyashita Y (2007) Activation of right inferior frontal gyrus during response inhibition across response modalities. J Cogn Neurosci 19:69–80

Cloninger CR (1987) Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science 236:410–416

Cook JW, Spring B, McChargue D (2007) Influence of nicotine on positive affect in anhedonic smokers. Psychopharmacol 192:87–95

Dawe S, Gullo MJ, Loxton NJ (2004) Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: implications for substance misuse. Addict Behav 29:1389–1405

Dawkins L, Powell JH, West R, Powell JF, Pickering A (2006) A double-blind placebo controlled experimental study of nicotine: I—effects on incentive motivation. Psychopharmacol 189:355–368

Dawkins L, Powell JH, West R, Powell JF, Pickering A (2007a) A double-blind placebo controlled experimental study of nicotine: II—effects on response inhibition and executive functioning. Psychopharmacol 190:457–467

Dawkins L, Acaster S, Powell JH (2007b) The effects of smoking and abstinence on experience of happiness and sadness in response to positively valenced, negatively valenced and neutral film clips. Addict Behav 32:425–431

Dawkins L, Powell JH, Pickering A, Powell J, West R (2009) Patterns of change in withdrawal symptoms, desire to smoke, reward motivation and response inhibition across 3 months of smoking abstinence. Addiction 104:850–858

Donny EC, Griffin KM, Shiffman S, Sayette MA (2008) The relationship between cigarette use, nicotine dependence, and craving in laboratory volunteers. Nicotine Tob Res 10:934–942

Doran N, Spring B, McChargue D, Pergadia M, Richmond M (2004) Impulsivity and smoking relapse. Nicotine Tob Res 6:641–647

Dougherty DM, Moeller FG, Steinberg JL, Marsh DM, Hines SE, Bjork JM (1999) Alcohol increases commission error rates for a continuous performance test. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23:1342–1351

Droungas A, Ehrman RN, Childress AR, O’Brien CP (1995) Effect of smoking cues and cigarette availability on craving and smoking behavior. Addict Behav 20(6):57–73

Etter JF, Vu Duc T, Perneger TV (2000) Saliva cotinine levels in smokers and nonsmokers. Am J Epidemiol 151:251–258

Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG (1991) Adult IVE. Hodder & Stoughton, London

Field M, Mogg K, Bradley BP (2004) Eye movements to smoking-related cues: effects of nicotine deprivation. Psychopharmacol 173:116–123

Field M, Santarcangelo M, Sumnall H, Goudie A, Cole J (2006) Delay discounting and the behavioural economics of cigarette purchases in smokers: the effects of nicotine deprivation. Psychopharmacol 186:255–263

Fukushima J, Fukushima K, Miyasaka K, Yamashita I (1994) Voluntary control of saccadic eye movement in patients with frontal cortical lesions and Parkinsonian patients in comparison with that in schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry 36:21–30

Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND (2002) Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry 159:1642–1652

Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, De Beurs E, Van Den Brink W (2008) The role of self-reported impulsivity and reward sensitivity versus neurocognitive measures of disinhibition and decision-making in the prediction of relapse in pathological gamblers. Psychol Med 38:41–50

Gurpegui M, Jurado D, Luna JD, Fernández-Molina C, Moreno-Abril O, Gálvez R (2007) Personality traits associated with caffeine intake and smoking. Prog Neuropsychopharm Biol Psychiat 31:997–1005

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO (1991) The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict 86:1119–1127

Hughes JR, Keely J, Niaura R, Ossip-Klein D, Richmond R, Swan G (2003) Measures of abstinence from tobacco in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res 5:13–26

Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S (2004) Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 99:29–38

Jentsch JD, Taylor RD (1999) Impulsivity resulting from frontostriatal dysfunction in drug abuse: implications for the control of behavior by reward-related stimuli. Psychopharmacol 146:373–390

Kalamboka N, Remington B, Glautier S (2009) Nicotine withdrawal and reward responsivity in a card-sorting task. Psychopharmacology 204:155–163

Koob GF, Nestler EJ (1997) The neurobiology of drug addiction. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 9:482–497

Krishnan-Sarin S, Reynolds B, Duhig AM, Smith A, Liss T, McFetridge A, Cavallo DA, Carroll KM, Potenza MN (2007) Behavioral impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in a smoking cessation programme for adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 88:79–82

Lamb RJ, Morral AR, Kirby KC, Javors MA, Galbicka G, Iguchi M (2007) Contingencies for change in complacent smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 15:245–255

Lejuez CW, Aklin WM, Jones HA, Richards JB, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Read JP (2003) The Balloon Analogue Risk Task, BART, differentiates smokers and nonsmokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 11:26–33

Leventhal AM, Ramsey SE, Brown RA, LaChance HR, Kahler CW (2008) Dimensions of depressive symptoms and smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 10:507–517

Lingford-Hughes A (2005) Human brain imaging and substance abuse. Curr Opin Pharmacol 5:42–46

Mann K, Günther A, Stetter F, Ackermann K (1999) Rapid recovery from cognitive deficits in abstinent alcoholics: a controlled test-retest study. Alcohol Alcohol 34:567–574

Marissen MA, Franken IH, Waters AJ, Blanken P, van den Brink W, Hendriks VM (2006) Attentional bias predicts heroin relapse following treatment. Addiction 101:1306–1312

McBride D, Barrett SP, Kelly JT, Aw A, Dagher A (2006) Effects of expectancy and abstinence on the neural response to smoking cues in cigarette smokers: an fMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:2728–2738

McDonald J, Schleifer L, Richards JB, de Wit H (2003) Effects of THC on behavioral measures of impulsivity in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:1356–1365

Meda SA, Stevens MC, Potenza MN, Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Andrews MM, Thomas AD, Muska C, Hylton JL, Pearlson GD (2009) Investigating the behavioral and self-report constructs of impulsivity domains using principal component analysis. Behav Pharmacol 20:390–399

Mitchell SH (1999) Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology 146:455–464

Mogg K, Bradley BP (2002) Selective processing of smoking-related cues in smokers: manipulation of deprivation level and comparison of three measures of processing bias. Psychopharmacology 16:385–392

Myung SK, Seo HG, Park S, Kim Y, Kim DJ, Lee do H, Seong MW, Nam MH, Oh SW, Kim JA, Kim MY (2007) Sociodemographic and smoking behavioral predictors associated with smoking cessation according to follow-up periods: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of transdermal nicotine patches. J Korean Med Sci 22:1065–1070

Niaura R, Abrams DB, Shadel WG, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Sirota AD (1999) Cue exposure treatment for smoking relapse prevention: a controlled clinical trial. Addiction 94:685–695

Nigg JT, Butler KM, Huang-Pollock CL, Henderson JM (2002) Inhibitory processes in adults with persistent childhood onset ADHD. J Consult Clin Psychol 70:153–157

Nollen NL, Mayo MS, Sanderson Cox L, Okuyemi KS, Choi WS, Kaur H, Ahluwalia JS (2006) Predictors of quitting among African American light smokers enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 21:590–595

Nørregaard J, Tønnesen P, Petersen L (1993) Predictors and reasons for relapse in smoking cessation with nicotine and placebo patches. Prev Med 22:261–271

Payne TJ, Smith PO, Adams SG, Diefenbach L (2006) Pretreatment cue reactivity predicts end-of-treatment smoking. Addict Behav 31:702–710

Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Lerman C, Benowitz N, Fiore MC, Baker TB (2008) Assessing dimensions of nicotine dependence: an evaluation of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale, NDSS, and the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives, WISDM. Nicotine Tob Res 10:1009–1020

Powell JH, Dawkins L, Davis R (2002a) Smoking, desire, and planfulness: tests of an incentive motivational model. Biol Psychiatry 51:151–163

Powell JH, Tait S, Lessiter J (2002b) Cigarette smoking and attention to pleasure and threat words in the Stroop paradigm. Addiction 97:1163–1170

Reynolds B, Richards JB, Horn K, Karraker K (2004) Delay discounting and probability discounting as related to cigarette smoking status in adults. Behav Process 65:35–42

Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H (2006) Dimensions of impulsive behavior: personality and behavioral measures. Pers Individ Differ 40:305–315

Rose JE, Behm FM, Salley AN, Bates JE, Coleman RE, Hawk TC, Turkington TG (2007) Regional brain activity correlates of nicotine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 32:2441–2452

Rubinstein ML, Thompson PJ, Benowitz NL, Shiffman S, Moscicki AB (2007) Cotinine levels in relation to smoking behavior and addiction in young adolescent smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 9:129–135

Shadel WG, Niaura R, Brown RA, Hutchison KE, Abrams DB (2001) A content analysis of smoking craving. J Clin Psychol 57:145–150

Shiffman S, West R, Gilbert D (2004) Recommendation for the assessment of tobacco craving and withdrawal in smoking cessation trials. Nicotine Tob Res 6:599–614

Spinella M (2002) Correlations between orbitofrontal dysfunction and tobacco smoking. Addict Biol 7:381–384

Velicer WF, Prochaska JO (2004) A comparison of four self-report smoking cessation outcome measures. Addict Behav 29:51–60

Verdejo-Garcia A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L (2008) Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders: review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32:777–810

Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Swanson JM (2004) Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results from imaging studies and treatment implications. Mol Psychiatry 9:556–569

Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Baler R, Telang F (2009) Imaging dopamine's role in drug abuse and addiction. Neuropharmacology 56(Suppl 1):3–8

Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Sayette MA, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH (2003a) Attentional bias predicts outcome in smoking cessation. Health Psychol 22:378–387

Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Bradley BP, Mogg K (2003b) Attentional shifts to smoking cues in smokers. Addiction 98:1409–1417

Waters AJ, Shiffman S, Sayette MA, Paty JA, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH (2004) Cue-provoked craving and nicotine replacement therapy in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol 72:1136–1143

Weinstein A, Cox WM (2006) Cognitive processing of drug-related stimuli: the role of memory and attention. J Psychopharmacol 20:850–859

West RJ, Hajek P (2004) Evaluation of the mood and physical symptoms scale, MPSS, to assess cigarette withdrawal. Psychopharmacology 177:195–199

West RJ, Russell MAH (1985) Pre-abstinence nicotine intake and smoking motivation as predictors of cigarette withdrawal symptoms. Psychopharmacology 87:334–336

West R, Ussher M (2010) Is the ten-item Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-brief) more sensitive to abstinence than shorter craving measures? Psychopharmacol 208:427–432

Yucel M, Lubman DI (2007) Neurocognitive and neuroimaging evidence of behavioural dysregulation in human drug addiction: implications for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Drug Alcohol Depend 26:33–39

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiat Scand 67:361–370

Zuckerman M, Eysenck S, Eysenck HJ (1978) Sensation seeking in England and America: cross-cultural age and sex comparisons. J Consult Clin Psychol 46:139–149

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant code 3527427). We thank Drs. Kiki Nikolaou, Ian Tharp, Mary Cochrane and Atsuko Inoue for their assistance with the recruitment and testing of participants in this study.

Ethics

This study complies with the current laws and ethical requirements of the UK. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of Goldsmiths, University of London and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant code 3527427).

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00213-011-2300-x

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Powell, J., Dawkins, L., West, R. et al. Relapse to smoking during unaided cessation: clinical, cognitive and motivational predictors. Psychopharmacology 212, 537–549 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-1975-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-1975-8